The Portella della Ginestra Anti-Mafia Memorial: a page in the history of protection written

On May 3 in the Pier Santi Mattarella Hall of the Sicilian Regional Assembly, Ars, in Palermo, a page was written in the history of Sicilian cultural heritage protection. And of the entire nation. During the conference The Portella della Ginestra Memorial. ’Civic’ Need for Restoration, edited by the writer, the initiation of the “declaration of cultural interest” of the Portella della Ginestra Memorial, located in the territory of Piana degli Albanesi, in the Palermo area, was announced. The event enters history by right, we said, because the recognition to the site of the necessary requirements for protection, invoked for so many years in the past, only now, at last, has come about thanks to Palermo Superintendent Selima Giuliano, daughter of Boris, head of the Palermo Mobile Squad, killed by Cosa Nostra in 1979, the very year in which the work began.

Respect for history and values overcame ideological and political divisions. The Conference saw a rare convergence of all political sides in the Ars and obtained the patronage of the highest institutions, the presidency of the Sicilian Region, the presidency of the Ars and three Departments (Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Productive Activities). Also at the same table were CGIL, Legambiente and the Portella della Ginestra Association, which represents the families of the victims who lost their lives on May 1, 1947, in what is the mother of all massacres at the beginning of Republican history. The booth is owed to Piana degli Albanesi Mayor Rosario Petta, who also organized the event.

After 43 years of waiting, in less than two months, it succeeded in getting the work’s bond initiated; in publicly committing Cultural Assets Councillor Francesco Scarpinato on the restoration and the Regional Anti-Mafia Commission on a further recognition, that of “a symbolic good of the entire nation,” to quote its president Antonello Cracolici, who spoke at the conference.

The Anti-Mafia and Anti-Heroic Memorial.

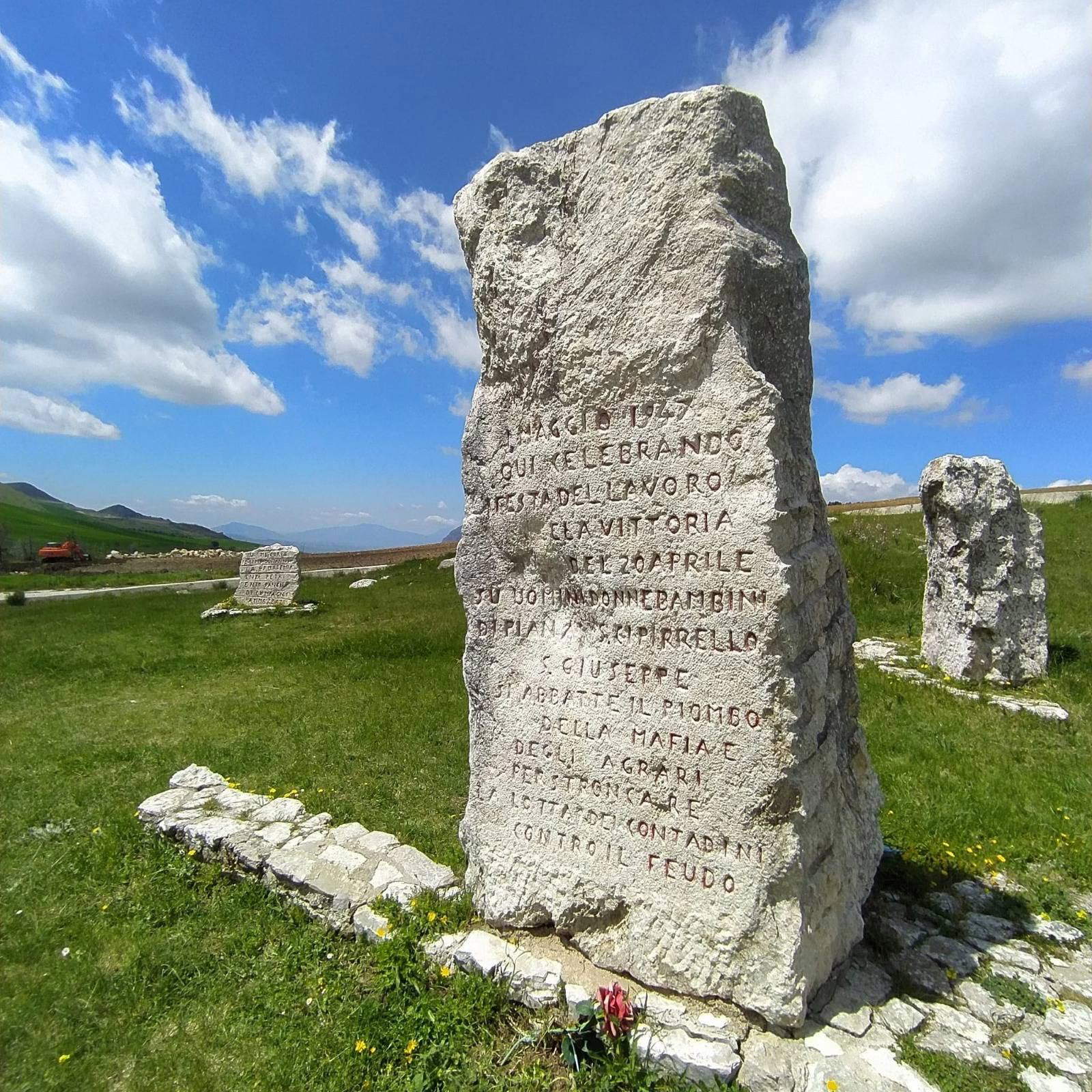

The Memorial is a work of civil commitment created between 1979 and 1980 by Ettore de Conciliis, an eclectic artist from Avellino, class of ’41, with the collaboration of painter Rocco Falciano and architect Giorgio Stockel. It is built on the plateau between Mount Pizzuto and the provincial road to San Giuseppe Jato below, where the massacre carried out by the bandit Salvatore Giuliano and his men occurred. On May 1, 1947, about two thousand workers, mostly peasants and laborers with their families, had gathered there to celebrate Labor Day, demonstrate against latifundism and in favor of the occupation of uncultivated land. Unarmed people paid in blood (11 dead and 27 seriously wounded) for the success reported in the Sicilian elections the previous April by the People’s Bloc with 30 percent of the vote. While internationally there was the rapid anti-communist evolution of U.S. foreign policy.

“The identity value of the installation,” writes the Superintendency, “is also enhanced by the artist’s choice to involve the entire community, starting with the design and then with the realization, making use of local workers for the composition of the elements and the processing of materials, deliberately selected in adherence to the characteristics of the place.” A dialogue with the population, committed to keeping alive the memory of the tragic event, which De Conciliis re-established with the same attention in the preparatory stages of the Palermo Conference.

From a historical-artistic point of view, the Memorial also represents the first work of land art in Sicily, preceding Burri’s Cretto in Gibellina (begun between 1984 and 1989), and one of the first works in Italy. It is a Stonehenge of the 20th century. From few other places emanates such secular sacredness. Exciting and destabilizing at the same time. De Conciliis whispers to posterity, and all it takes is a few gestures, as if with chalk he had marked the scene of the crime on the ground: the trajectory of the gunshots indicated by the trazzera that enters the Memorial’s enclosure and the silhouettes of the fallen with stone blocks that resemble menhirs. A first stone reproducing the outline of the mountain bears the date of the massacre; the “Sasso di Barbato” is dedicated to the Italo-Albanian socialist Nicola Barbato, founder and leader of the Sicilian Workers’ Fasci; two others bear vernacular verses by the peasant poet Ignazio Buttitta and the names of the victims; and at the end of the path stands the stele commemorating the tragic event (Mazza, 2022).

How is it possible to bind a work that is less than 70 years old and whose author is living?

It may be interesting to understand, even for other cases in Italy, how it was possible to declare a work that does not meet the requirements of being 70 years old and the author no longer living, a cultural asset, achieving a goal that had been awaited for 43 years, as many as there have been since the creation of the Memorial. As explained in an interview with CGIL, where I recounted how the idea of the conservation restoration project for the Memorial was born, from the first meeting with Ettore De Conciliis for a solo exhibition I had curated in 2021 in Venice to the appointment of thefollowing year in Portella della Ginestra, the spring was the realization of the conservative conditions of the site by its author himself, which risked compromising the reading of the metaphorical meanings he attributed to the Memorial. After more than four decades, signs caused by weathering and soil settlement were evident. There was an urgent need for action now. We made this clear at the first awareness conference on February 3 at the Messina Regional Museum, in the presence of De Conciliis himself. But to do it properly, the involvement of the Superintendency could not be ignored.

I wanted to understand if there was room for recognition of the necessary requirements for protection since, unlike what the regulations require, it was a work made less than seventy years ago and whose author was still living. There was, then, the historical conjuncture, we said, that the head of the Superintendency of Palermo is Selima Giuliano. I met her, with her staff, the following March 7. The “window” granted by the Cultural Heritage Code was immediately identified: the constraint under Art. 10(3)(d), which states “immovable and movable things, to whomever they belong, which are of particularly important interest because of their reference to political, military, literary, artistic, scientific, technical, industrial and cultural history in general, or as evidence of the identity and history of public, collective or religious institutions.”

And here a general premise is needed. According to the Code, for a cultural property to be such there must have been either a verification of cultural interest or a declaration of cultural interest. In Article 10, a fundamental distinction is made between cultural property of public ownership, for which verification must intervene, and cultural property of private ownership, for which a declaration of cultural interest is required under Article 13 (so-called constraint), the procedure for which is then set out in detail in Article 14.

So, in general, the distinction of the two procedures, verification and declaration, is based on the different legal nature of the owners (possessors or holders) of the property in question. Article 10, co. 3 (d), on the other hand, overcomes this distinction (“to whomever they belong to”), allowing one (the Memorial) owned by a public entity (the Municipality of Piana degli Albanesi) to be declared a cultural asset as well.

So, the recognition of the Memorial as a cultural asset subject to protection necessarily took place with a deminutio: to recognize it for its artistic interest would have had to wait another 27 years. On the other hand, the declaration of the Memorial’s cultural interest, pursuant to the aforementioned norm, was possible for the Superintendence, “both because of its reference with history and as a unique testimony to the identity and history of collective institutions.” It is, in other words, an asset declared to be of “relational” cultural interest. As with some public stadiums or velodromes. For the purposes of protection, and in the perspective of subsequent conservation work, nothing changes.

Nevertheless, the Memorial has its own relevant historical-artistic value, being the first work of land art in Sicily, with a substantial bibliography to support it, among which stand out the names of critics of the caliber of Enrico Crispolti, Maurizio Marini, Claudio Strinati, Maurizio Calvesi, to name but a few.

The project for the conservative intervention

Architect Alessandro Di Blasi’s preliminary already exists, with the valuable artistic direction of Ettore De Conciliis himself. The further contribution of the writer will consist in helping to define the choices of method and guidelines in the logic of minimal intervention, the guiding principle of any restoration, which must be even more so in this case because of the specificities of the work in question and the environmental context in which it is located. So, for example, we will have to limit ourselves to the interventions that are indispensable to restore the plastic complex in its material consistency and form in order to keep intact the legibility of contents and messages that we want to ferry to posterity: that is why it is, also, a civically necessary act. A stone that loses its verticality sees “tampered with” the metaphorical charge of that tension toward the sky that is a promise of “resurrection” of the ideals for which helpless people lost their lives. But to restore that verticality will not have to opt for invasive, albeit camouflaged, solutions. And again, even the natural washout of a freshly hewn boulder to suggest an anthropomorphic profile or the idea of the sacrificed donkey weakens the artistic act that intervened on that natural element to make it take that particular form. While mosses and lichens, will not necessarily have to be removed, as a sign of nature’s interaction with the land art work, which is characterized precisely by this direct relationship with it.

The project will also include interventions for the enhancement and fruition of the Memorial: suffice it to say that the site is completely devoid of signage, the captioning apparatuses (in Italian and English, but also arbëreshe, the language of the Albanian ethno-linguistic minority of Piana degli Albanesi) and dedicated lighting for a purely evening visit.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.