The KMSKA, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp: a new museum idea

Is it pure utopia to imagine a place where art is closely mixed, almost not recognizing its boundaries, with play and curious discovery? Habit leads, oftentimes, to conceive of the museum space as a majestic silent temple, where art is sacred, unattainable, untouchable, and committed to pushing the daring patron overbearingly out of his or her narrow world. Rare are the cases where it is perceived as home, at its own measure and proper only, which not only teaches, but listens and amazes. And it is astonishing to discover how in a European city, Antwerp, stands a building with a limestone facade with neoclassical columns and carved busts that embodies exactly these values and desires. The KMSKA (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen - Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp) is a house of art, a place that mixes, with natural continuity, old and new, a treasure chest of discoveries and experiences that, after an extremely turbulent history, as of September 24, 2022, has reopened its doors to the public after eleven years of closure.

The Southern Quarter (Zuid), which houses the Royal Museum, has been the focus of recent urban development following the demolition of the ancient city walls and the 16th-century fortress of the Duke of Alba, but right in the middle of these major renovations lies the KMSKA where, with great caution and respect for history and, at the same time, a spirit of innovation, something new has been created. A perpetual dialogue between ancient and modern.

Usually, museums are expanded through the creation of new annexes as in the very famous case of the Louvre’s glass pyramid, but here an expansion was opted for that would exploit as much as possible the pre-existing surface and the vertical of the building to return a new space, but in continuity with the modern and contemporary artworks. Before its closure, the museum had turned into a faded and ruined building, the mosaics had lost their natural luster and the exterior statues their luster. Every corner, with the new opening, has been restored regaining its original splendor. The majestic glazed ceilings, designed in the late 19th century by architects Jacob Winders and Frans Van Dijk, have been retained in the name of a sought-after continuity, and the particular path between old and new is also developed through the search for light. The “new museum” part, created by KAAN Architects, pursues light and all the infinite facets of color that correspond to it. The new galleries with bright white walls are interrupted only by the colors of the artworks, as if opening a window to the world, and are reflected like a contemporary Narcissus on a highly polished white resin floor.

“Daylight in a museum is such a rare thing these days,” pressed architect Dikkie Scipio of KAAN Architects during the presentation of the new museum. “With daylight, God or nature decides whether it is more gray or more yellow, and the slant of the light shifts slightly during the day. You have more connection with the outside world, and I love that principle.” And it is precisely on this principle and immeasurable strength that the Rubens Gallery (room 2.2), which has remained largely unchanged, is based.

The mammoth space was created specifically to find shelter for three monumental paintings by Flemish master Pieter Paul Rubens: the Baptism of Christ, the Enthroned Madonna surrounded by Saints and the ’Adoration of the Magi, with the latter playfully conversing with three camels of antique red cloth taken from the canvas, on whose backs the weary visitor might even sit. The “old” part of the museum has been rearranged in such a way that visitors can wander through time wandering through rooms painted antique red, olive green or Pompeii red just as they did in 1890, admiring now magniloquent canvases by Rubens, now small studies by Van Dyck. Everything at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp has been renovated and restored, from the velvet armchairs to the parquet flooring, from the technical facilities to the plaster ceiling decorations. The museum’s focus falls, of course, on the Flemish masters of whom it has a very substantial collection, but it also boasts many works by foreign artists such as the Italian Amedeo Modigliani or the French Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

During the brief period of Dutch rule, King William I presented the academy museum with a painting by Titian, the only work by the Italian master in a Belgian public collection, but far more important to the fortunes of the KMSKA was the legacy left in 1841 by Chevalier Florent van Ertborn, a former mayor of Antwerp, which included 144 paintings, including works by Flemish primitives such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling, as well as international pieces such as Jean Fouquet’s Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubs and four panels by Simone Martini.

During the 19th century, the Antwerp Academy became an internationally renowned hub, and one of the admission requirements was the donation of representative example of one’s work and a self-portrait. Thus, well-known names such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Alexandre Cabanel and August Kiss were included in a “Museum of the Academicians” and later in the collection.

Quickly, the works became too many for the building, which was moved to the more capacious current hub after a very violent fire, but once again the space was soon depleted thanks to continued donations from prominent families, followed by purchases by the museum itself. Another particularly important 20th-century figure was curator Walther Vanbeselaere, who acquired paintings by Flemish expressionists such as Constant Permeke, Frits Van den Berghe and Gustave De Smet, but also works from the international art scene such as Edgar Degas, Hans Hartung, Karel Appel, Ben Nicholson and Giacomo Manzù.

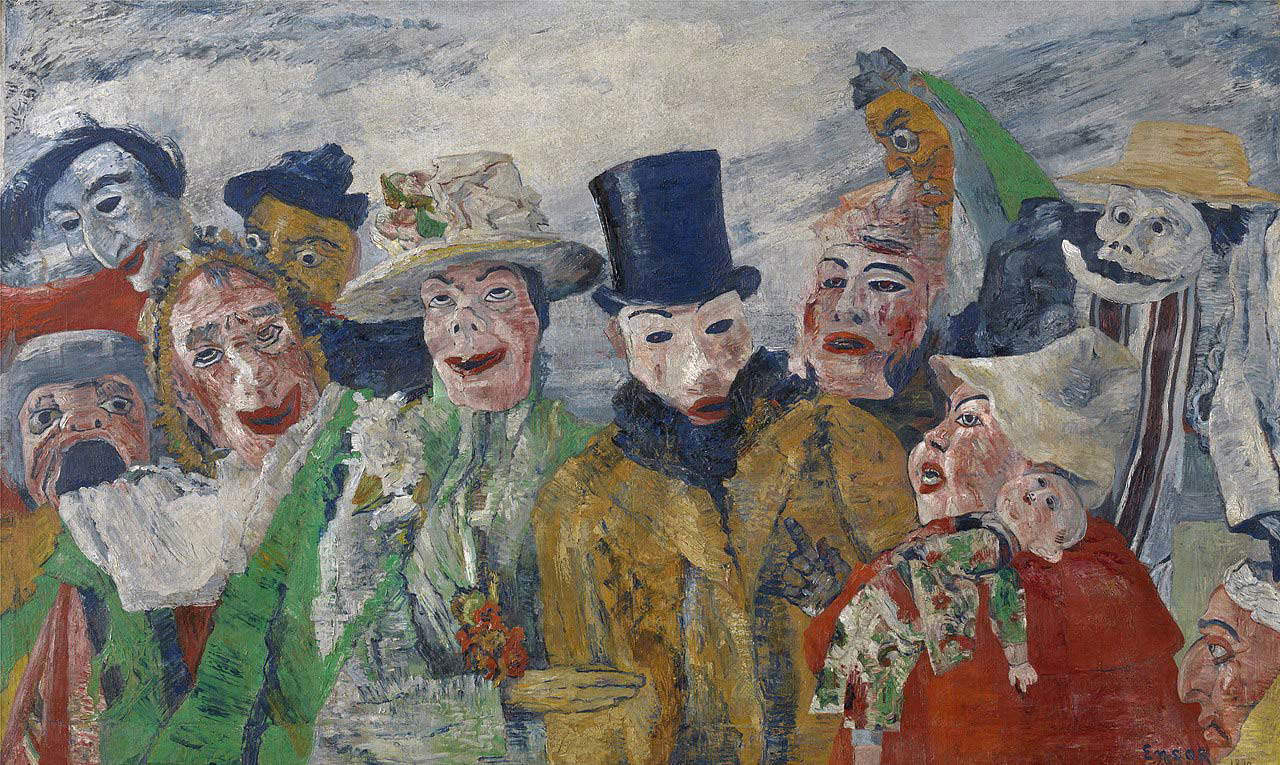

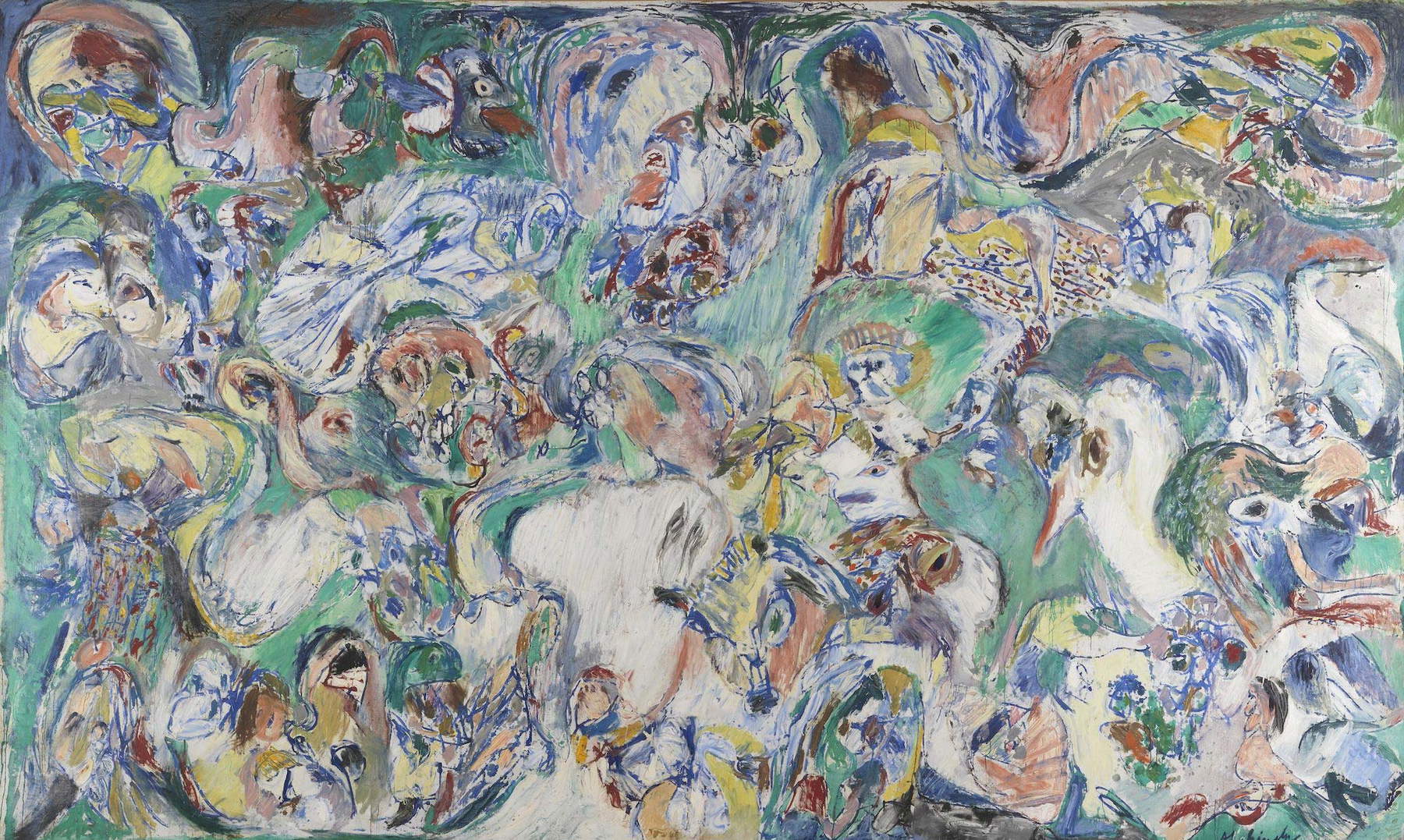

“Three works symbolize the three pillars of our collection,” says Siska Beele, curator of KMSKA: "Jean Fouquet’s Madonna, James Ensor’s The Intrigue, and Pierre Alechinsky’s The Last Day." And it is precisely James Ensor ’s that the museum has the world’s largest collection, which has been included in the whiteness of the new rooms, representing the transition between ancient and modern times. There are three monographic rooms dedicated to the Belgian painter and engraver, and the visitor discovers that he or she is never just a passive spectator, but is invited to take part in the works, playing, for example, a piano inserted into the space, which, mirrored to the floor along with the colorful paintings, concurs to become a brand new and unrepeatable great work of art. Different is the case with the 1890 world of eerie masks, L’ intrigo, which is discovered to stand alone in an immense white wall.

Like L’ intrigue, Jean Fouquet’s Madonna is also set in a solitary wall, this time painted a strong antique red, and it dialogues with Der diagnostische Blick by contemporary Luc Tuymans, a work depicting a very close-up of a male face with a lost look. Jean Fouquet’s Madonna is part of the Melun Diptych, painted around 1455 for the collegiate church of Notre-Dame, fifty kilometers from Paris: at the Antwerp museum there is only the right-hand side depicting the Madonna and Child surrounded by cherubs.

In this place, somewhere between play and dream, there are many contemporary works that are in dialogue with the ancients, creating totally new suggestions. In the continuous conversation between ancient and modern, monitors are serenely inserted, both for adults and children, which lightly explain the work in front of which they are placed. To date, the KMSKA houses a collection of more than 9,000 objects, of which about 650 are on display, divided by rooms according to a very particular and innovative order.

Instead of following a chronological order or by author, the curators created a thematic path depending on what the works convey or represent. And so, in the Hall of Powerlessness, a Rodin from 1884 finds itself communicating with a Jan Coulet painting from the first half of the 16th century or a very modern Basquiat. “We came quite quickly to the decision to display the collection thematically rather than chronologically,” writes, in the museum catalog, Nico van Hout, curator and head of the collection. “In this way, we can show a wonderful ensemble of the highest quality, with only a few masterpieces in each room. We anticipated that our visitors would expect a new way of presenting the work. Experience has shown that people’s historical knowledge is becoming less complete and they cannot easily place key figures such as, for example, Charles V or Napoleon in time. The same goes for knowledge of artistic styles, such as Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque. Moreover, our collection has strengths and weaknesses: we are very strong in the period from the 15th to the 17th century, and with our extensive Ensor collection we make a nice transition to the modern. But we don’t have more than a handful of good works from the 18th century.”

Walking through gallery after gallery and finding oneself unearthing new themes and trying to guess them is a game that allows one to become a child again and fill one’s eyes with new discoveries and new ways of seeing the world. The curious viewer, once a child, might even find himself tempted to fix a tavern scene by Adrien van Ostade hanging crookedly to follow the fall of the painting’s protagonist and wander almost aimlessly between “leisure,” “abundance,” “fame,” “suffering,” and “redemption” and learn new “life lessons.” What the museum proposes, in the end, is nothing more than a journey through everyone’s life among the various emotions and feelings that sooner or later, one way or another we are bound to experience. And discovering that, life, can take the colors and shapes of a work of art, makes it more interesting and even more worth living.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.