Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado has always been attentive to environmental issues, a topic that has become more topical now than ever due to the climate changes that are preoccupying the entire planet. Think of global warming, melting of ice, pollution of the oceans and seas, so much so that as is well known, programs and actions have been identified to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all, starting with the goals ofAgenda 2030. Among the main causes of so-called climate change is deforestation, as cutting down forests causes emissions: in fact, once felled, trees release the carbon they have stored. Forests absorb carbon dioxide, which is why they are important for making the planet “breathe,” but cutting them down limits nature’s ability to keep emissions out of the atmosphere.

Because of its extent, the Amazon rainforest is considered the Earth’s green lung: consider that it absorbs 150 to 200 billion tons of carbon and because of this it is able to influence the regulation of climate and biological cycles on the entire planet. The WWF, among the first organizations to call attention to the drama of Amazon deforestation, says that in the last 30 years we have lost an average of 12,000 square kilometers of tropical forest per year, but on some occasions as much as 28,000 square kilometers, and that in the first six months of 2022 as much as 3,988 square kilometers of Amazon forest were destroyed, more than three times the area of Rome, registering record values for this time of year, three times as much as in 2017.

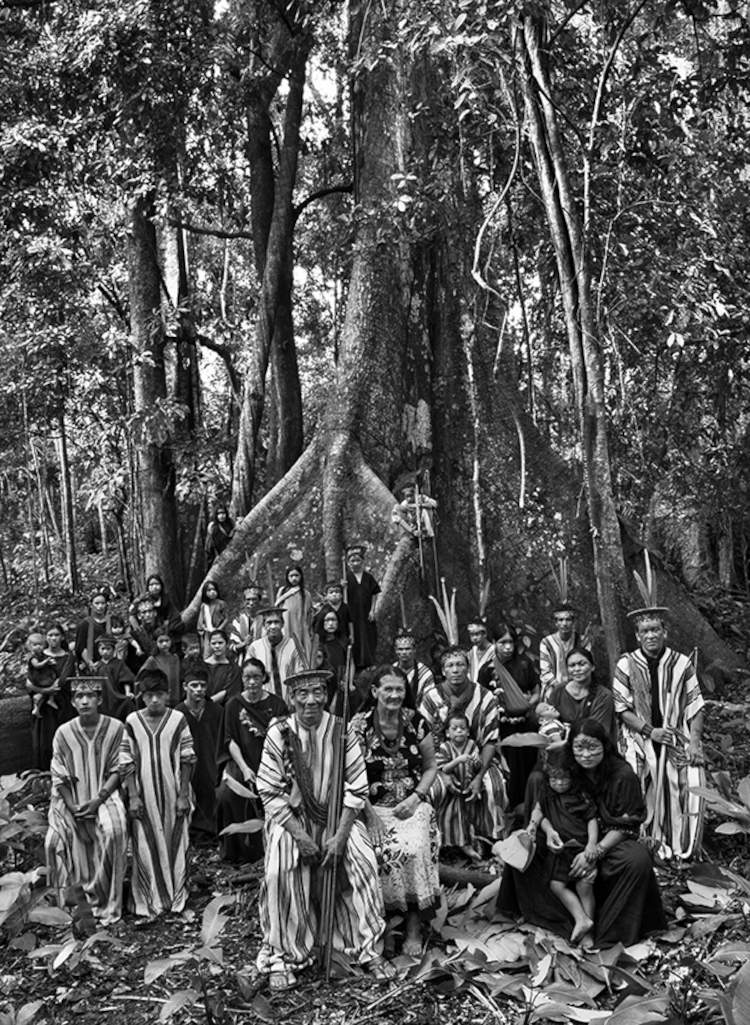

Salgado lived, documented and photographed the Amazon rainforest for seven years: he immersed himself in this extraordinary landscape to listen to the sounds of the forest, the singing of the birds, the roar of the rivers, to admire the mountains and the great trees that make up the immense rainforest, and to come into contact with the indigenous peoples who live it and with whom they have established a visceral and indissoluble relationship with it from long ago. His major photographic project Amazônia is from 2021, through which Salgado wants to offer “a testimony of what remains of this immense heritage, which is in danger of disappearing.” A heritage that includes both its lush vegetation rich in biodiversity and its native peoples. Through his project, the photographer wants to highlight the beauty of this nature and its inhabitants, but above all he intends to make the observer reflect on its fragility and therefore on the need to protect it. In the words of the photographer himself, “In order for life and nature to escape further episodes of destruction and depredation, it is up to every single human being on the planet to take part in its protection.”

The Amazônia project is now on view until November 19, 2023 in Milan, at the Fabbrica del Vapore, promoted and produced by Comune di Milano|Cultura, Fabbrica del Vapore and Contrasto with Civita Exhibitions and Museums and General Service Security, with curatorship by the photographer’s work and life partner Lélia Wanick Salgado, on the occasion of which the latter conceived of a true immersion in the forest through more than two hundred photographs depicting the vegetation, rivers, mountains, and people that populate the Brazilian Amazon to “emphasize the beauty of this nature and its inhabitants, as well as its ecological and human dimensions, all elements that are so threatened today and that it is essential to protect and preserve.”

The great environmental and landscape theme is addressed in Salgado’s photographs from different aspects, from aerial views of the forest to flying rivers, torrential rains, mountains, and Islands in the Stream. The only way to be able to realize the true size of the forest is to observe it from above, from an airplane or helicopter: what will be seen below us is a vast green mantle crossed by rivers that describe curved and sinuous lines within the forest. This is seen, for example, in the shot depicting the Mariuá River Archipelago, where the forest seems to create a line with the sky bulging with clouds. During the rainy season, rivers overflow their banks, sometimes giving rise to lakes and lagoons. It is rare to see the skies above the forest as a pristine blue expanse: the clouds always offer a different spectacle. They are an integral part of the Amazon, whether small or large, benevolent or menacing. Even in the forest, where vegetation can obstruct the view, they are always present and it is unlikely that the day will end without heavy rainfall. Or they tower above the Rio Negro, filtering the light reflecting off the surface of the water.

Among the most extraordinary and probably least known phenomena in the Amazon rainforest are the so-called flying rivers. Moisture-laden aerial rivers that form over the Amazon rainforest: in fact, this is the only place in the world where the air moisture system does not depend on evaporation from the oceans. Each tree disperses hundreds of liters of water a day, creating aerial rivers even larger than the Amazon. Scientists have estimated that if 17 billion tons of water were poured into the ocean from the Amazon each day, 20 billion tons would rise from the jungle into the atmosphere at the same time. Flying rivers influence the climate patterns of the entire planet and, in turn, are affected by deforestation and global warming. Scientists say that due to accelerated deforestation and ongoing climate change, the basin’s ground-level temperature has already risen by 1.5°C and is estimated to rise by an additional 2°C if the current trend remains unchanged. As a consequence of global warming, annual precipitation is feared to be reduced by between 10 percent and 20 percent.

Sky-high peaks rise from the lowlands: the highest mountain in Brazil is Pico da Neblina, which exceeds 3,000 meters in height. Rainforest covers the lower slopes with vegetation that thins more and more until it is interrupted by the cliffs. A rather peculiar geological formation is Mount Roraima: it is a flat-topped mountain reaching 2800 meters that is home to endemic plant and animal species.

Next in the Amazon rainforest is the world’s largest freshwater archipelago, the Anavilhanas Archipelago, characterized by islands of different shapes emerging from the waters of the Rio Negro. The larger islands are covered with dense tropical vegetation, while the smaller, low-lying ones may disappear temporarily or even permanently when the water level rises more than twenty meters in the rainy season. The view from above is truly astonishing.

The rivers give indigenous peoples high-protein foods that are essential for their nutrition. The tribes have learned to keep a safe distance from the natural floodplains, which, in the rainy season, are invaded by streams to the point of flooding. Indeed, within the Amazon rainforest live various indigenous peoples with whom Sebastião Salgado has had the opportunity to come into contact in his travels. In his shots he immortalized twelve indigenous groups: Awa-Guajá, Marubo, Korubo, Waurá, Kamayurá, Kuikuro, Suruwahá, Asháninka, Yawanawá, Yanomami, Macuxi and Zo’é. The photographer has taken portraits of indigenous men and women, including a shaman conversing with spirits before ascending Mount Pico de Neblina, young women with typical ornaments, and whole families of indigenous people. Over the past decade of his work, Salgado has been working among the Amazon tribes and having become aware of their reality, he reiterated that these communities have suffered from the fires that have devastated the forests and are in serious danger from the encroachment of miners, loggers and cattle ranchers into territories reserved for the exclusive use of the indigenous people. “These indigenous peoples are part of the extraordinary history of our species,” Salgado stressed. “Their disappearance would be an extreme tragedy for Brazil and an immense loss for humanity.”

For Sebastião Salgado, all these images made over a period of years testify to what survives before further progressive disappearance. “My wish, with all my heart, with all my energy, with all the passion I possess, is that in fifty years this exhibition,” referring to the Amazônia project, “will not resemble a testimony of a lost world. The Amazon must continue to live and always have in its heart its indigenous inhabitants,” he concluded.

All photos © Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.