In recent days one of today’s most important Italian poets, Valerio Magrelli, published an alarming article on the increasing number of contemporary art sculptures made of all kinds of materials and in random and more or less useless forms that are now routinely placed in the streets and squares of Rome. A short, measured and elegant text in which the Roman poet quotes the review made in 1962 by Giovanni Urbani of the Spoleto exhibition “Sculptures in the City,” that is, about the first landing in a historical Italian city of contemporary sculpture as mere urban furniture. Double quotation, actually, because it moves from an article an which Federico Giannini quoted in “Finestre sull’Arte” a bitter and prophetic review that could have been written yesterday and talking about Rome, which is summed up in the title that Urbani himself had given it, “The Aesthetics of the bolt.” After that, if with ease anyone can today find Magrelli’s text on the Internet, the same is not true for the one Urbani published in “Il Punto,” a Roman magazine directed by Vittorio Calef on which Pasolini, Wilcock, Citati, Pandolfi or Castello, among others, wrote, closed in 1965, shortly after the death of Enrico Mattei who had wanted it. And it is for this reason, that is, to make it easily accessible, that I am republishing it today in Finestre Sull’Arte. With a small clarification. That in that review Urbani once again confirmed himself not as one who ideologically set himself against modernity, but as one who was perfectly aware that the main reason for the preservation of the art of the past, the work on which he has informed his entire life, lies in seeing it for what it first is: the unsurpassable root of today’s art, of course when that is what it is. And on Urbani’s judgment of today’s art (as he, significantly, preferred to call contemporary art) I make two personal accounts. One, the affection with which Mario Schifano spoke of Urbani telling me still happy and amazed about the note in which, after one of his first Roman exhibitions, Urbani had written to him, “I thank you Maestro for reconciling me with today’s art,” adding Mario; “understand me, a boy, I thank you Maestro...” The other is from the early 1990s, when Urbani again advised me to go and see an exhibition by a then very young Giuseppe Ducrot - “he makes beautiful sculptures and draws in an extraordinary way” - that had recently opened in Rome at Carlo Virgilio’s gallery. What I did was to discover there another boy who was also a great artist and whose depth is now recognized by critics not so much Italian, but international.

Giovanni Urbani

The Aesthetics of the Deadbolt

(in “Il Punto” July 14, 1962)

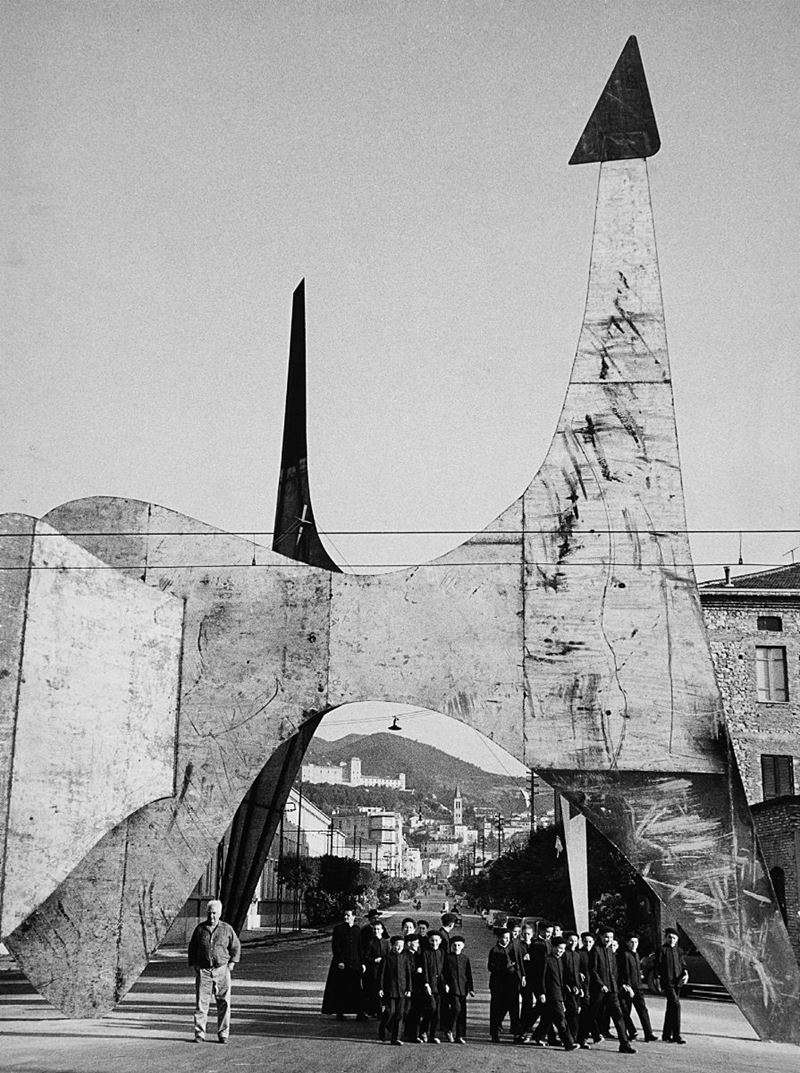

There is no doubt, this year the real new fact of the Spoleto Festival is the exhibition “Sculptures in the City.” New not only for the Festival, but also in regard to sculpture in general and to that particular kind of city. It is certainly the first time that such a marriage between the “new” and the “old,” between the freest (perhaps because, at present, also the most default) of the arts, and a reality as binding as is, or should be for every civilized person, the intact historical-artistic physiognomy of an ancient city.

Has the experiment succeeded? Those who say yes and those who say no: that is, since in these things one opinion is as good as another, and disparities prove only a certain movement of ideas and interest, one must conclude that yes, it certainly succeeded. The sculptures are what they are, but in any case by the best sculptors in the world; there are a great many of them, which, for an exhibition, is certainly not a bad thing; they do not contrast at all with the environment, that is, if they do not beautify the city, neither do they disfigure it. In addition, Giovanni Carandente must be credited with the organization, which is perfect and on a cyclopean scale; as well as with the set-up, which is highly refined in its details and, except for a few errors, kept on the edge of great wisdom in the choice of viewpoints, in the dosage of effects and of “effectacci” that are not disreputable.

So, if someone invincibly dislikes the show (and I am among them) there is nothing to be done: he must resign himself to leaving his dissent devoid of good reasons. Unless one goes down a path that is perhaps too narrow to let good reasons pass, but wide enough for a thread of thought....

First of all, is it then certain that it is an exhibition? A statue in a square or street never stands on its own, but is part of a context in which it comes to assume the very specific role of a monument. If this were not so, and if this did not imply for the individual work of art a rigid condition of belonging and almost of organic solidarity to the architectural place in which it takes up its abode, we would have to speak of Florence, for example, or Venice, or Rome as venues for gigantic exhibitions that have in their catalogs, among others, the David, the Colleoni, Marc’Aurelio, etc. The first, admittedly not very serious, overpowering of common sense that we have to endure in Spoleto, lies precisely in the fact that here, some ninety statues erected in the manner and condition of monuments, are not monuments but pieces of an exhibition. The thing, I repeat, is not serious because the exhibition will end sooner or later, and Spoleto will be returned to its usual features. But let’s assume that any patron falls in love with the exhibition, buys it in bulk and gives it to the city: all it takes is a thoughtlessness like this for the pieces of the exhibition to mutate into actual monuments, the joke becomes reality, and Spoleto, from being a town known for its millennia of history and its highly mobile face, becomes the place on earth where, one fine morning in ’62, the inhabitants woke up with ninety more monuments.

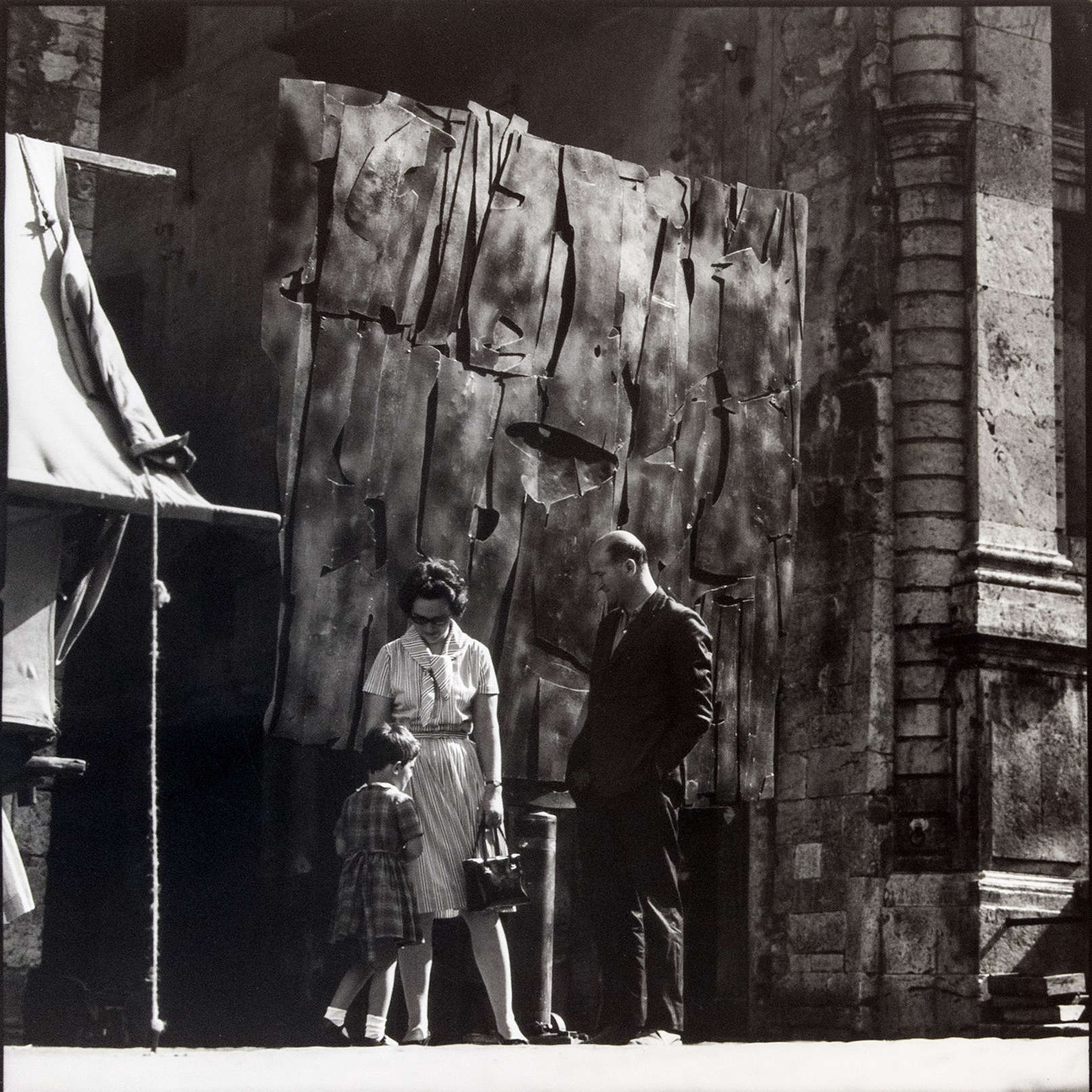

As long as, however, the exhibition remains an exhibition, moreover a successful one, let us deal with this one and try to explain why we do not like it. To put it briefly: we do not like it precisely because it is well done; because, from a noble and venerable city, we did not expect such an easy abdication of its nature as a city for functions - albeit decent, but certainly a bit superficial, or at least in contrast to those that hinge on the very human act ofliving - that are required of any exhibition stand or pavilion. In short, it is well and truly sad that the aesthetics of the bolt, the scrap, the rusted iron and the useless object make one, in sensibility and consciousness with temporary, with the way we regard an ancient city.

It will be said that to pose the problem in this way is unfair to the sculpture of today, because by stating that its aesthetic is that of the bolt, etc., one is implicitly giving a negative judgment that would instead be all to be proven. This may be so, but for my own part I remain quietly convinced that even if it is not brought directly to bear on sculpture, this judgment is legitimately derived from the fact that if a rusty bolt placed like a statue against a medieval wall makes a pleasing effect, this means that for our aesthetic sensibility medieval wall and rusty bolt are the same thing. Now, taking into account that a medieval wall should have a somewhat more complex meaning than a rusty bolt, who do we want to hold responsible for this mutilating leveling, this absurd loss of meaning and reality: the medieval wall, or rather not what prevents us from discerning a difference between wall and bolt, that is, our taste, our aesthetic education and in short, current sculpture? One could add to the dose by remembering that today’s sculpture has taught us to enjoy the famous bolt still in another environmental situation: outdoors, among the branches of a garden or on the edge of a pond. Thus helping us to accomplish a further emptying of meaning and reality: with respect not only to deadbolts and walls, but also to nature.

Unfortunately, the indictment we are thus bringing against sculpture, in a way, backfires on us, on what we would have believed to be most noble, lofty and dignified pursuits, in the value system accredited by our civilization. I mean the defense and preservation of what is called the historical-artistic-natural heritage. It is a fact that to educate taste in the love of deadbolts, and consequently to educate it in the appreciation of the scenery in which deadbolts figure best (medieval walls, gardens and ponds), is also to work in the most effective and convincing manner-because precisely based on the obscure and very fertile soil of taste and fashion-in favor of respect for history, for artistic and natural beauty. Is this not a sacrosanct program, and one that goes to the pride of the best part of our culture to have expressed for years in the stringent forms of historical studies, aesthetics, criticism and even jurisprudence? Well, an exhibition so conceived surely does for the preservation of an ancient city like Spoleto (where this preservation must be born, that is, it is in the consciousness of its inhabitants), much more than those studies and laws. Only, take it or leave it: what it teaches to safeguard is the massive stupidity of the rusty bolt, and what is safeguarded is not the essential reality of the ancient or of nature, but the empty aestheticizing worship of their bare appearances. On the other hand, if these appearances are not secured, how can we defend the invisible and more substantial reality behind them? And are we sure that we can still form an idea of this reality that is not in some way determined by the aesthetic pleasure that is precisely of the appearances to procure us?

So we are at a crossroads: either we endure the stupid beauty of the bolt, or we give up saving history, art and nature. Those who feel the shame of being dragged into thinking such a dilemma will also understand why one cannot but detest the well-executed Spoleto exhibition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.