Ten things to know about Robert Mapplethorpe

Robert Mapplethorpe (New York, 1946 - Boston, 1989), an emblematic and provocative figure of 20th-century photography (on view at the Stanze della Fotografia in Venice with Robert Mapplethorpe. The Forms of the Classic, from April 10, 2025 to January 6, 2026), left an unmistakable artistic legacy, capable of combining seduction and glamour in a visual language that openly defies social and moral conventions. His photographs, which range from portraits to still lifes, from nudes to the exploration of the erotic and sadomasochistic sphere, are not limited to mere aesthetic representation, but stand as profound reflections on controversial issues such as homosexuality, sexuality and identity. American writer Joan Didion masterfully summarized his art, highlighting Mapplethorpe’s ability to apply a classical form to “unthinkable” images, creating a visual short-circuit that amplifies the expressive power of his works.

Mapplethorpe was a complete artist. From his artistic roots, influenced by minimalism and the classical tradition, to his meticulous photographic technique, based on image construction and maniacal attention to detail, Mapplethorpe was able to orchestrate bold provocations and is known for his ability to transform the human body into a cult object, elevating it to a symbol of beauty and desire. He was able to transform inner turmoil into a public phenomenon, elevating eroticism into an art form and challenging the conventions of a society often captive to its own prejudices. His figure is also often affected by clichés that relegate him to a mere provocative photographer: instead, the complexity and depth of an artist who was able to transform photography into an instrument of inner investigation and social denunciation should be restored to the American photographer. As Germano Celant stated, Mapplethorpe has been able to avoid being swallowed into the abyss thanks to a “classical procedure, which draws on the roots of art history from Greek culture to modernism, as reflected in the plastic reality of his images and in the statuesque representation of the bodies portrayed. The tornado of shadow and perversion, which threatened to engulf him, subsided thanks to the spatial and geometrically defined, almost an ancient constructive rationality of the subjects.”

Here, then, are ten things to know about Robert Mapplethorpe in a journey through the experience of the classical, the ideal of beauty and the search for the representation of desire, three fundamental keys to understanding his art.

1. His photography dealt with controversial themes

Robert Mapplethorpe is universally recognized as one of the most influential and provocative photographers of the 20th century. His stylistic signature is unmistakable: he combines glamour and seduction in a dialogue that seems incompatible, an oxymoron that defies aesthetic and moral conventions. His photographs, characterized by an almost sculptural formal perfection, deal with topics considered controversial, such as homosexuality, eroticism and explicit sexuality. Joan Didion, celebrated American writer, pointed out how Mapplethorpe was able to apply a classical form to “unthinkable” images, creating a contrast that amplifies the visual power of his works.

This approach is not limited to the superficial beauty of images but invites the audience to reflect on deep and often uncomfortable issues. Mapplethorpe has been able to transform photography into a tool for personal and social exploration, using the medium to question cultural taboos and celebrate human diversity. His work stands as a challenge to late 20th-century society, eschewing the constraint of denial that conventional morality imposes when it comes to sex and corporeality. That intimate turmoil, which the author senses by delving into his inner landscape, changes status, becoming public knowledge. “Mapplethorpe,” Denis Curti has written, “images what late twentieth-century society - and in some cases even the society in which we live today - seeks to remove; in other words, he eschews the constraint of denial that conventional morality imposes when talking about sex and corporeality. In doing so, that intimate turmoil, which the author senses by delving into his inner landscape, changes status, becoming public knowledge. The praise of desire and the poetics of the body then become effective ways of recognizing oneself.”

2. Photography for Mapplethorpe was a kind of performance

For Mapplethorpe, photography was not simply a means of capturing images; it was an authentic performance. Each shot was the result of a meticulous process in which nothing was left to chance. His studio became an artificial stage where the photographer orchestrated every detail with maniacal precision. “Being photographed by me becomes an event ... everything is completely under my control. There are no snapshots. Nothing is left to chance. A kind of performance takes place between me and my subject,” Mapplethorpe declared.

This total mastery of the scene allowed him to create images that were both constructed and sincere, where the unnaturalness of the composition translated into a form of emotional truth. The relationship between the photographer and his subjects turned into a kind of ritual, a unique performance that was reflected in the visual power of his works. His ability to control every element of photography -- from the pose of the subject to the quality of light -- demonstrates an absolute dedication to artistic perfection.

3. Form and intensity are two fundamental concepts for understanding his art

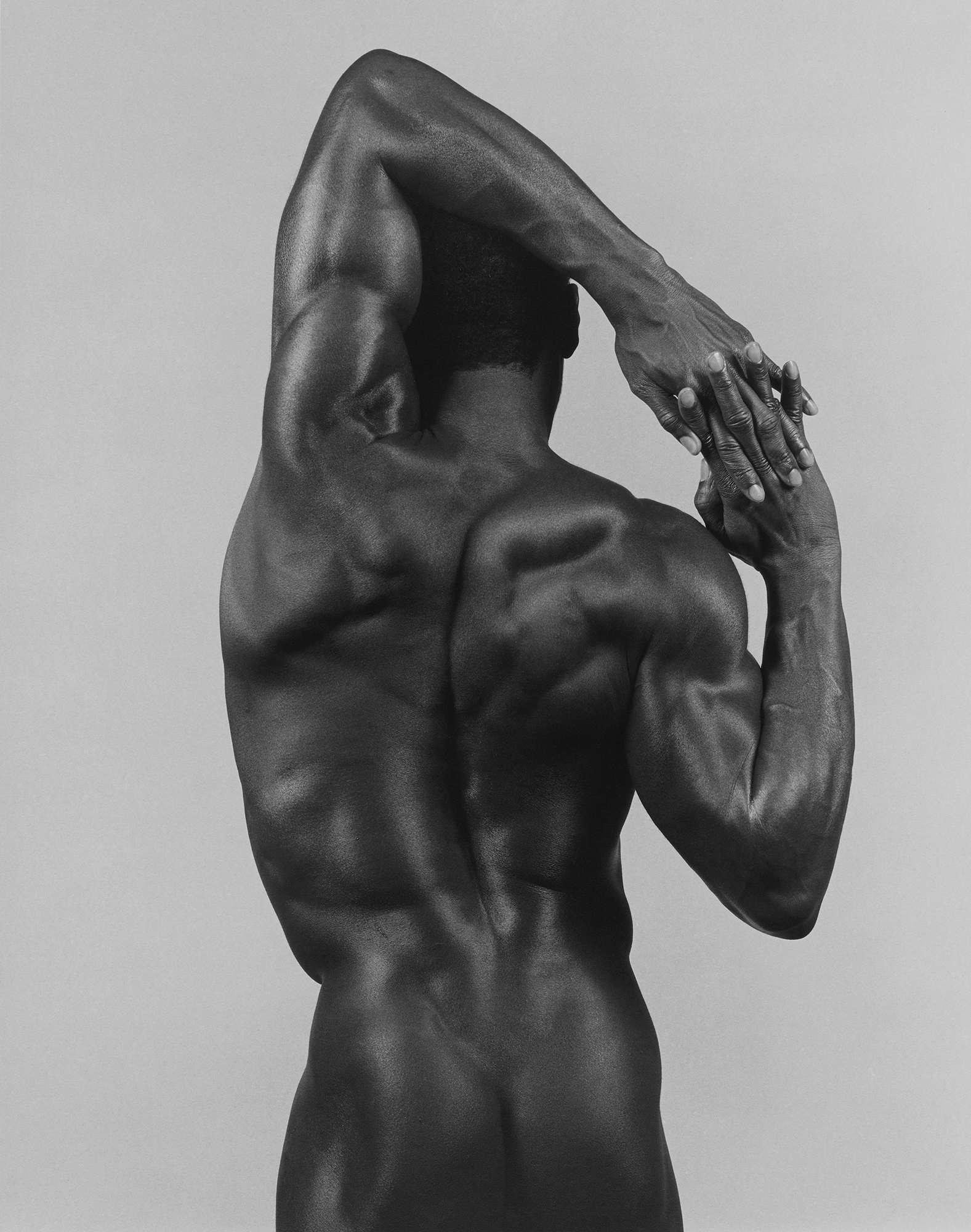

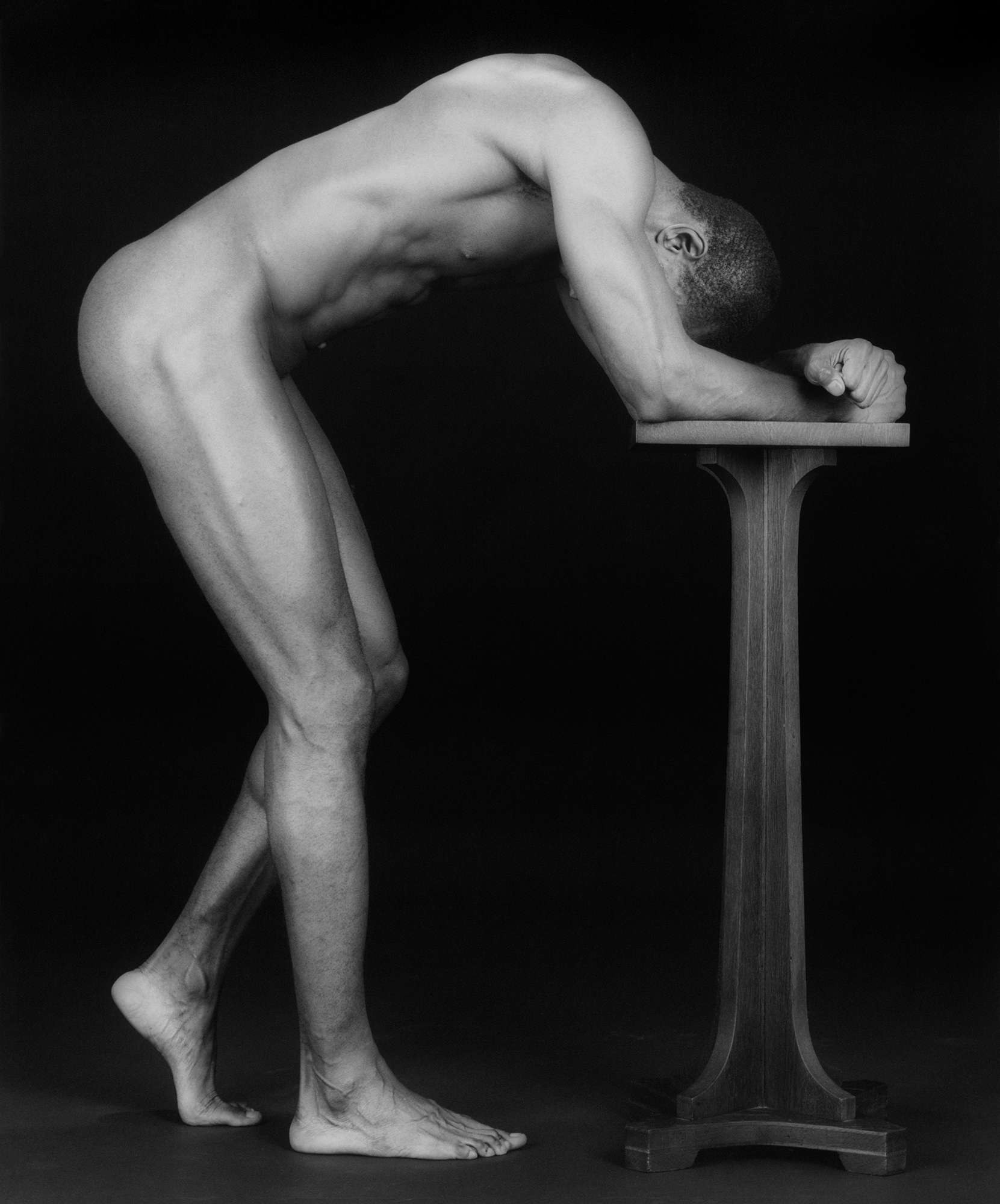

Two fundamental concepts for understanding Robert Mapplethorpe’s work are form and intensity. These principles guided every aspect of his work, from the choice of subjects to the composition of images. Form was an absolute value for him: he sought geometric perfection in his photographs, often drawing inspiration from classical statuary. An emblematic example is the famous 1988 Torso, which recalls the harmonious proportions of Renaissance sculptures.

Intensity, however, emerged from Mapplethorpe’s ability to capture the emotional essence of his subjects, turning each image into a visceral experience for the viewer. His Hasselblad camera-a manual tool that required great precision-allowed him to sublimate the relationship between the parts of the composition, creating perfectly balanced images that transcend time and space.

4. There are recurring subjects in his art

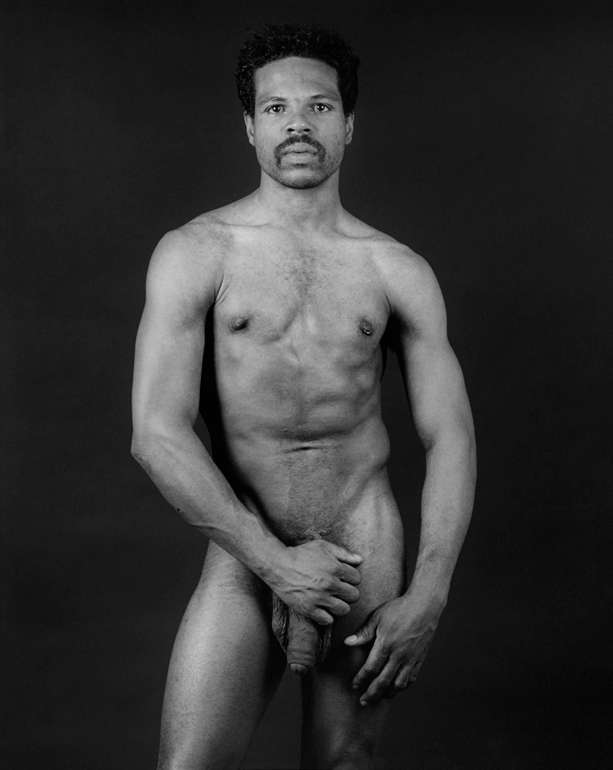

Robert Mapplethorpe has explored a wide range of subjects in his work, but certain themes recur with particular insistence, becoming almost hallmarks of his style. These include portraits, still lifes and nudes, each approached with a unique approach and unmistakable sensibility. His nudes, in particular, are often imbued with a fetishistic and sadomasochistic aesthetic, making them simultaneously attractive and disturbing. Mapplethorpe has been able to celebrate the sensuality of the human body, male and female, with a gaze that recalls classicism, but at the same time he has not hesitated to explore the darker territories of desire and perversion.

The frontality of his images, the almost maniacal attention to anatomical details, and the care in composition and lighting all contribute to an atmosphere of intense erotic charge that defies social conventions and moral hypocrisies. Mapplethorpe had the audacity to photograph explicitly sexual subjects, objectifying the vision and opening new horizons in the representation of the human body. Likewise, he incorporated African American figures into the tradition of art photography, breaking with dominant aesthetic canons and giving voice to an often marginalized minority.

5. Flowers were among his favorite subjects: here’s why

Photographs of flowers hold a special place in Robert Mapplethorpe’s artistic output. These seemingly simple and innocuous subjects become in his hands powerful metaphors for beauty, fragility, and sensuality. Mapplethorpe was able to transform petals and stems into works of art of extraordinary emotional intensity, evoking the same passions and disturbances found in his nudes and portraits.

Each flower is photographed with an almost scientific precision, with maniacal attention to detail, shadows, light and texture. Mapplethorpe recorded every single variation, whether epidermis, leaves, petals, rocks, skulls or shells, using light to achieve the same effect as the nudes, often covered with chrome pigments to enhance their textural quality. For him, flowers are not mere decorative objects, but universal symbols of life and death, beauty and transience.

6. Classical art was of great importance to Mapplethorpe

Mapplethorpe’s photography is deeply rooted in the classical tradition of Western art. Universal values such as perfection, balance and measure permeate his works, making them timeless and universal. Through his conscious use of symmetry and geometry, Mapplethorpe was able to create images that dialogued with art history: from the myths of Greek antiquity to Renaissance academies to contemporary American minimalism.

This connection between ancient and modern is central to his work and is one of the most fascinating aspects of his work. For Mapplethorpe, recourse is a deliberate project. In him universal values such as perfection, measure, balance, intensity and naturalness all connect together. “In him,” writes Alberto Salvadori, “universal values such as perfection, measure, balance, intensity and naturalness all connect together. These are values that have always been ascribed to the ’classical’ and are understood to be perpetual and current. In this and because of this his photography is classical: they are timeless images that escape the nature of historically determined products. His work is also classical because through it we nourish our knowledge because of the variety and complexity of his life and historical experience. Mapplethorpe’s is a balancing game between matter and spirit in which recurring themes and allusions are present: the relationship between ancient and contemporary, myth and reality, sculpture and skin, ecstasy and pangs. An iconic universe that, more than 30 years after his death, never ceases to fascinate.”

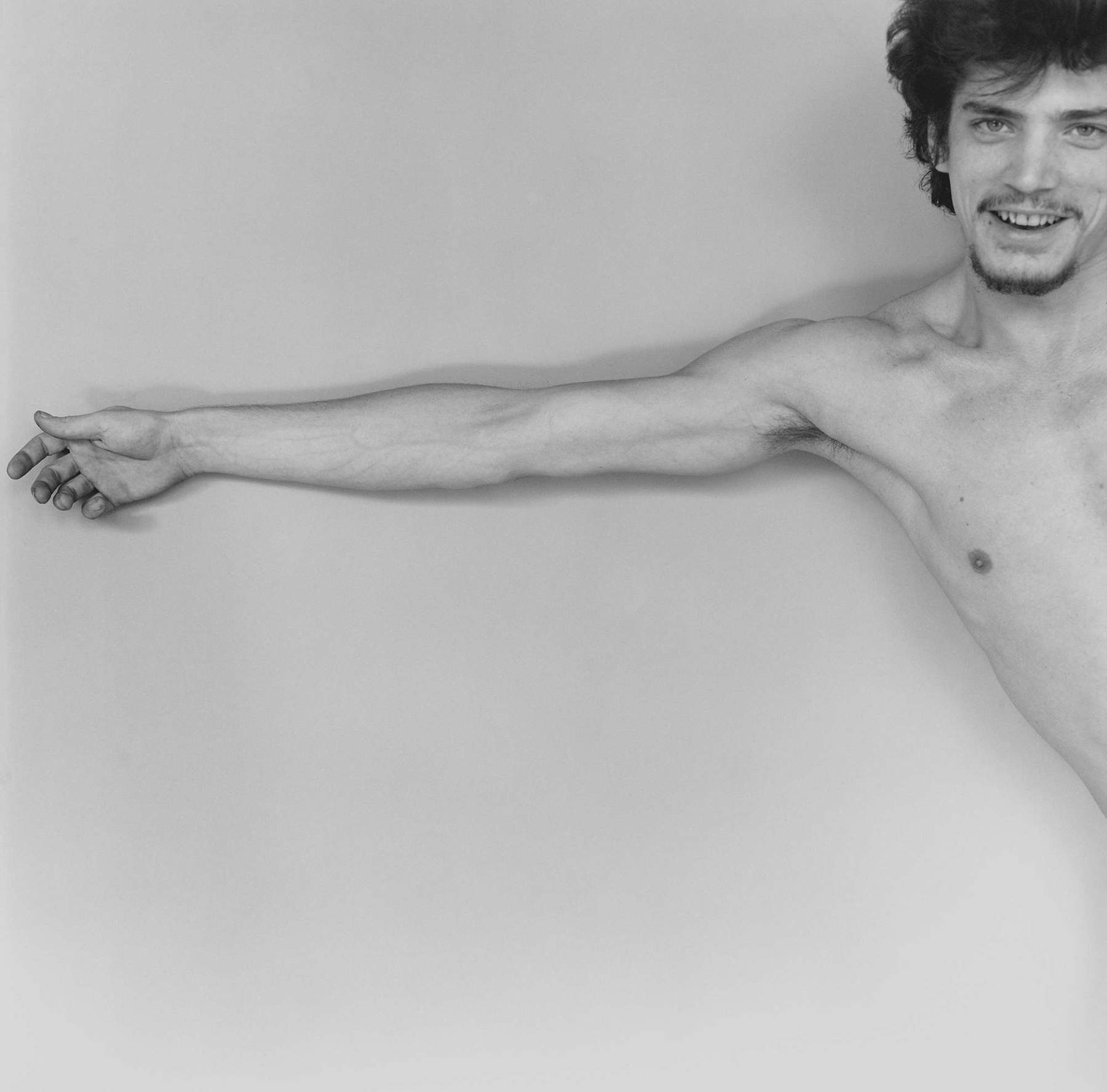

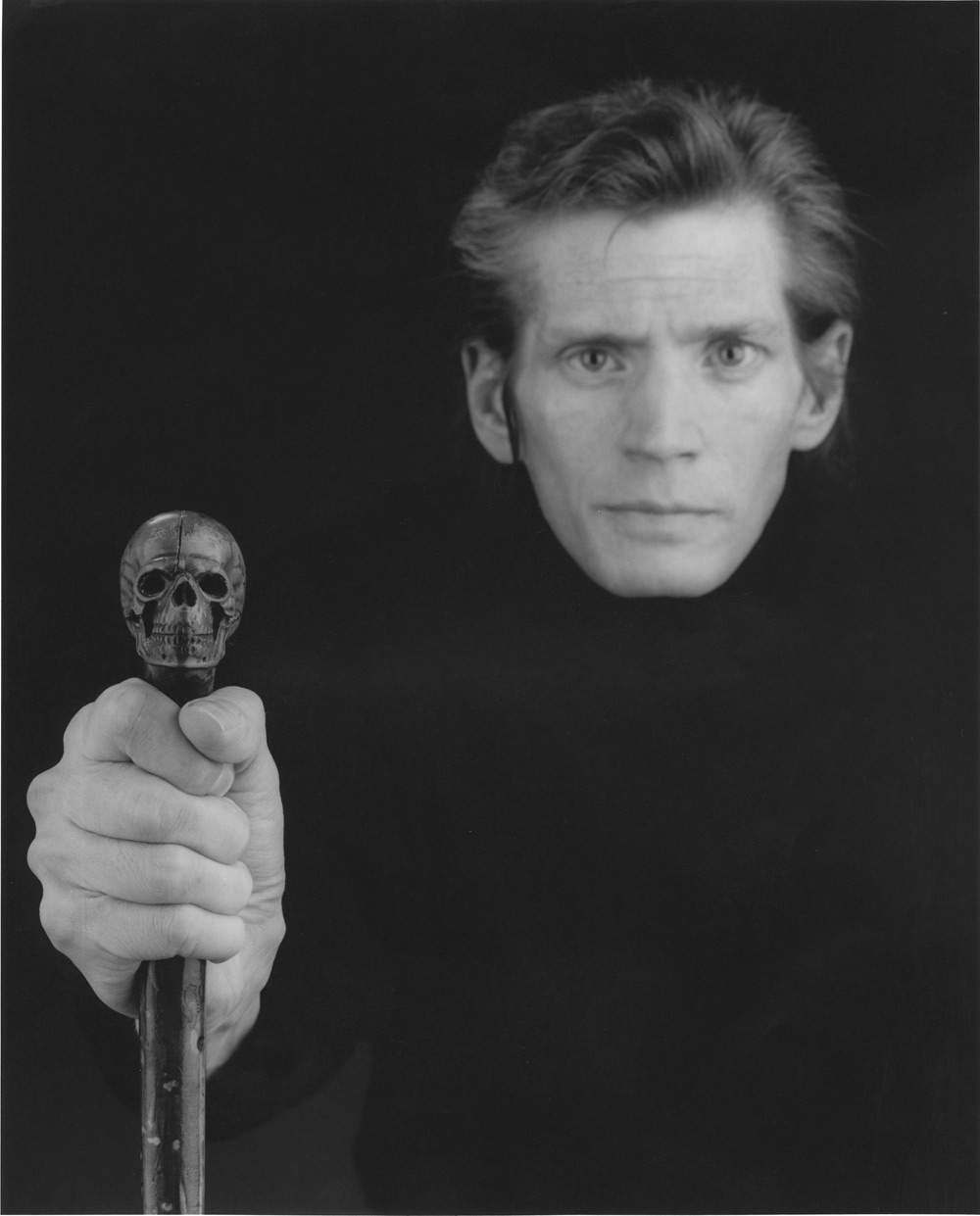

7. Self-portraits are a tool of introspection for him

Self-portraits representone of the most intimate and emblematic aspects of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work. Through these autobiographical shots, the photographer explores his own identity with boldness and vulnerability. The self-portraits are never mere physical representations but true visual manifestos, tools of introspection and self-exploration that investigate themes such as eroticism, mortality and sexual ambiguity. In some famous self-portraits - such as the one in which he wears women’s clothing or the one in which he presents himself with a whip - Mapplethorpe challenges social and aesthetic conventions to create images that are both provocative and elegant.

In these self-shots, the artist stages his own image, transforming it into a symbol of rebellion and expressive freedom. Mapplethorpe has been able to use his own body as a tool of investigation, exploring the boundaries between identity and representation. His self-portraits are a mirror of his soul, an invitation to look beyond appearances and confront the shadowy areas of human existence.

8. Photographic technique: a “directorial mode” to sublimate reality

Robert Mapplethorpe did not consider himself a mere transcriber of reality: he knew he was an image-maker. His approach to photography, called the directorial mode, was based on total control of the scene, from the choice of subjects to composition, from lighting to posing. Every detail was precisely studied and calibrated in order to achieve an end result that reflected his artistic vision. For Mapplethorpe, the negative represented the culmination of a long creative process: once developed, there was no room for changes or second thoughts. The proofs, on the other hand, constituted a ground for experimentation and research, a mental place to make the necessary editing.

The selection process was fundamental: making choices as a working practice. Polaroids, used especially at the beginning of work sessions, served as a “notebook,” a tool for jotting down ideas and defining compositions. Later, Mapplethorpe adapted this to the square shape of his faithful Hasselblad, a camera that allowed him to exert even greater control over the final image. He read bodies and volumes like a sculptor, arranging them in poses to create volumetric effects, guided by a precise pattern. Repetition with slight variations became the focus of the work and, in contrast to his peers, Mapplethorpe imparted a strong intensity to the images through long exposures, as short as 20 seconds, obsessed with quality.

9. With his relationship between the sacred and the profane he reinterpreted his Catholic heritage

Coming from a very religious Catholic family profoundly influenced Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, resulting in a bold and evocative mixture of the sacred and the profane. This dichotomy manifests itself in his exploration of the human body, elevated to an object of worship and desire, but also investigated in its fragility and mortality. Mapplethorpe was able to translate into images the tension between spirituality and carnality, between sin and redemption, that characterizes the Catholic tradition.

His photographs thus become a kind of pagan ritual, in which the body is elevated to a symbol of beauty and transcendence, but also exposed to vulnerability and pain. According to Denis Curti, Mapplethorpe “triggers in the mind of the viewer of his compositions a constant shift from the diabolical to the sublime, from attraction to its consequent sublimation. The resultant is the repeated enactment of a ceremonial.”

10. Perfection as the ultimate goal

An obsession with technical quality was central to Mapplethorpe’s work: every image had to be perfectly in focus, shadows in the right place, nothing haphazard, right angles and perpendicular lines, no irregularities. For Mapplethorpe, perfection was not a mere technical virtuosity, but an ethical requirement, a way to pay homage to the beauty of the world and to communicate his artistic vision as clearly as possible. This quest for perfection translated into maniacal attention to detail, obsessive control of composition and lighting, and spasmodic care for the printing and final presentation of the work. The fusion of all these elements generated perfect photographs, the ones he wanted. Perfection and beauty thus became complementary to the concepts of form and intensity.

Today, his gaze, says Denis Curti, remains “unique and unrepeatable, because it contains the collective desire to find a place where one can reappropriate, without prejudice, the vital spaces necessary to express oneself in full freedom. Photographs have the task of transferring the ephemerality of feelings to the concreteness of experiences. [...]. In his short existence, things happened all at once. As if to say: life, often, does not proceed on continuous and parallel tracks.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.