Reportage from TEFAF: a tour of ancient art at the 2024 edition of the Maastricht fair

The European Fine Art Fair, TEFAF, a near-legendary annual event where everything takes on out-of-the-ordinary proportions, from the quantity of exhibitors to the turnout of the public to the mind-boggling bargaining figures. The numbers are impressive and it is no coincidence that, over the years, the Maastricht fair has taken on the character of a true pilgrimage for gallerists, collectors, art experts and ordinary enthusiasts. The quality of the works on display is ensured not only by the impressive list of artists represented, but also by the extremely strict vetting process that affects every single booth: once the set-up is complete, on the Tuesday before the opening the exhibitors are ousted and a large team, consisting of more than two hundred examiners (academics, curators, experts, restorers, etc.) methodically analyzes each artifact, assessing its quality, state of preservation, and validity of attribution. It is not uncommon, walking among the stands, to catch some dissatisfaction among those who have been refused a tag, or had to change it at the last second, but the strict judgment of the committee is not appealable and is, in fact, one of the strengths of the entire event.

When one approaches for the first time, this fascinating and complex reality, one does so almost on tiptoe, in fear of being overwhelmed by so much exuberance, and carefully chooses the time of the visit; the first two days (Thursday and Friday) are off limits and one enters only by invitation, among museum directors (this year it seems there were more than three hundred), curators and major collectors. During the weekend there is a peak in visitors, and the risk is that you may have to wade through the crowds to admire the most popular pieces up close, as if you were at the Louvre or the Uffizi. For those who have no ambitions to shop (at least at these very high levels) and just want to enjoy this sort of impromptu, multifaceted museum of wonders to the fullest, it is therefore best to opt for one of the last days, the midweek days, when the bulk of the work, for gallery owners, is now over. The biggest sales, the six-figure ones, are already finalized, and among exhibitors there are those who take the opportunity to visit each other’s booths and those who dispose of correspondence from their PCs: someone does not fail to post on social media from museums in neighboring cities, but, in general, a more relaxed atmosphere prevails and there are more opportunities to exchange opinions and ideas, or to ask about works that go beyond the economic demand.

Even on a Monday morning, however, there is no shortage of queues for entry to TEFAF: first one is queued for access to the parking lot, then, after passing through the huge, futuristic spaces of MECC (a conference and exhibition center opened in 1988 and expanded and renovated several times, thelast one in 2021), one runs into a long line to go through security, and moreover, the memory of the four men, in suits and ties, who smashed a display case with sledgehammers in the 2022 edition, accomplishing a multimillion-dollar jewelry heist, is still alive.

TEFAF

TEFAF TEFAF

TEFAF TEFAF

TEFAF TEFAF

TEFAFOnce inside, as the audience disperses into the vast entrance hall, one is greeted by the customary installation by Tom Postma Design (Amsterdam) who, since 2001, has been curating these large Spatial flower design concepts that promise to accompany the transition from everyday life to the magical world of the art fair. Indeed, when one realizes that the sumptuous flower arrangements do not merely float but move through space, rising and falling, one abandons all reverential fears and is imbued with an almost childlike sense of joy, finally grasping that sense of great feast for the eyes (and mind) that can be experienced by those who visit TEFAF for the sheer pleasure of it.

A punctual account of what was on display at the fair would be impossible, and even just listing the most important works, or the most highly rated ones, would be tedious and pedantic: so take my notes for what they are, a series of impressions of what struck me most, selected and sorted according to subjective criteria, the result of my sensibility and training, without any claim to exhaustiveness. I am not going to tell you about the contemporary section but only about ancient art, painting and sculpture; after all, as one of Italy’s ablest art journalists says, “you go to TEFAF for that.”

A first aspect that strikes one, wandering around the stands, is the unprecedented attention given to the work of women artists, an impression confirmed by the presence of a special section, clearly visible on the event’s website. The operation undoubtedly makes sense from a market perspective, with the largest museums well attentive to smoothing out that gap in gender representation that is well present in public collections, but it allows us to discover works of definite impact and fascinating female stories. Particularly focused on the theme is the pavilion, entirely devoted to women painters, by Rob Smeets Old Master Paintings (Geneva), where among the delicate Pomo “Copied from the Natural” by Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), and the large canvas with Samson and Delilah by Diana de Rosa (1602-1643), attention was captured by the portrait of Antoinette Gonsalvus (1592) by the Bolognese Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), one of the most striking, and admired, works of this edition. Depicted in half-figure, against a dark, uniform background, little Antoinette is dressed in luxurious clothing that accentuates the contrast with her obvious hypertrichosis, a condition that caused an irrepressible proliferation of hair on her face. The child holds a letter that tells her story and says she is the daughter of “Pietro Huomosalvatico,” the famous Peter Gonsalvus, a native of Tenerife who, brought to the court of Henry II as a natural curiosity (he himself suffered from hypertrichosis), had a humanistic culture and married a lady-in-waiting of Catherine de’ Medici. Antoinette’s gaze, immediate and vibrant, more so than that of the hitherto known version of the painting (preserved at Blois Castle), captures all the spontaneity of her four years old (approximately) and strikes deep: the author does not give in to morbid curiosity about the unusual phenomenon but restores all the child’s naive humanity. Beaten at auction in 2023 on a starting base of €80/120,000, this touching portrait sold for a record €1,500,000, and was exhibited in Maastricht with a valuation that had already tripled, a truly astounding result for an artist, admittedly very prolific, but whose name is not yet familiar to the general public.

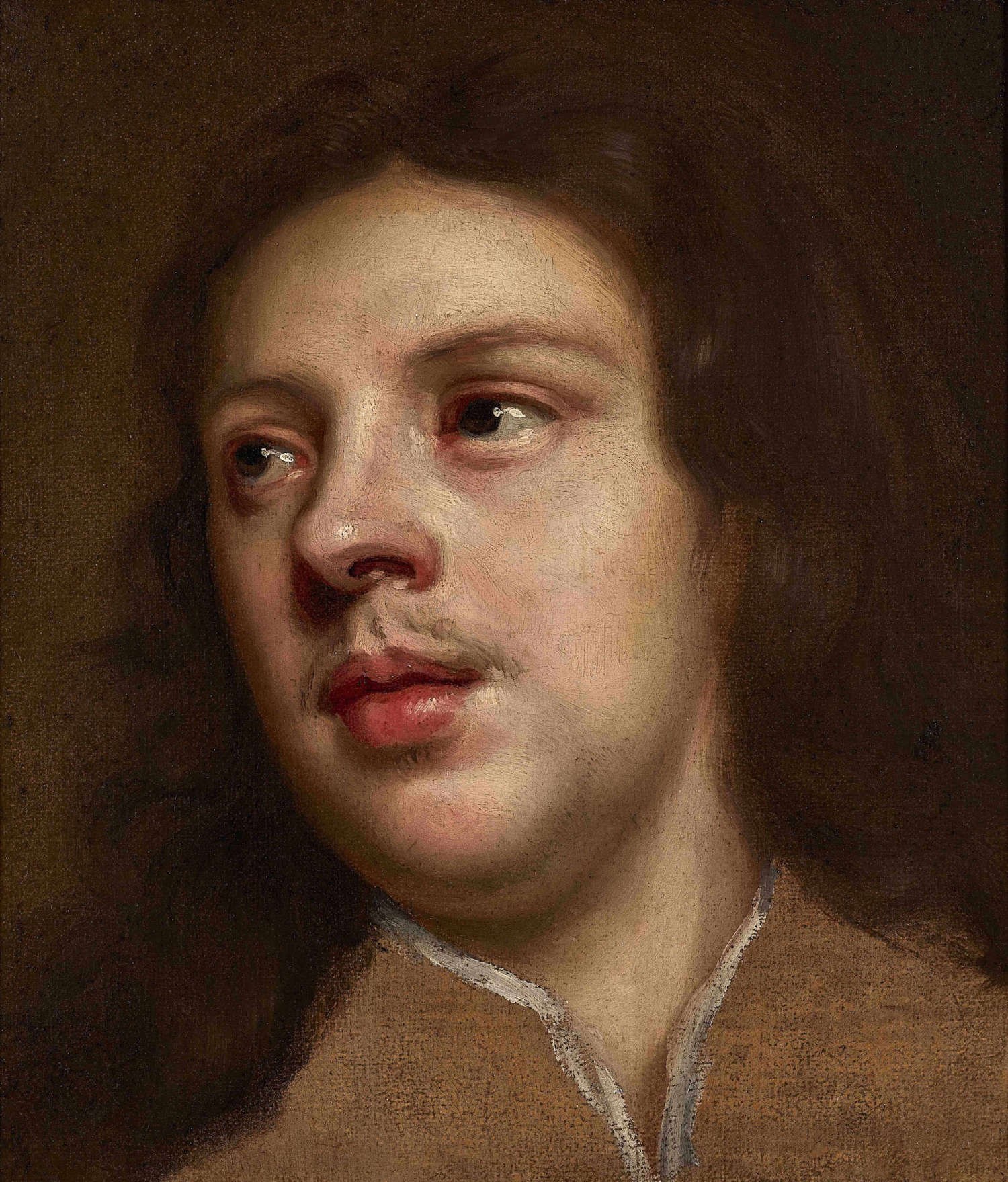

Also an important rediscovery is the one presented by The Weiss Gallery (London), with an oil sketch (c. 1670) by Mary Beale (1633-1699), one of England’s first professional women painters: reversing the traditional relationship between the man-artist and the woman-muse, Mary portrayed her husband Charles, a cloth merchant and amateur painter, with fresh vivacity, resulting in an image entirely focused on the rendering of facial expression. Mary experienced good fortune in the genre (in 1677 alone she was commissioned to paint 83 individual portraits), but it is her more intimate and spontaneous portrayals of friends and family that best convey her painterly skills.

Of an entirely different character is the work of Marie-Victoire Lemoine (1754-1820) exhibited by Brun Fine Art (London): the Young Woman Making Cheese, shown at the Salon of 1802, sought to transcend the usual genres of the genre scene and the portrait, areas that were intended to be more congenial to female talent, by proposing amusing allegorical meanings masked behind precious textural effects, with political overtones whose value we struggle to fully understand today. Marie-Victoire, with her sisters and a cousin, all skilled painters, formed an exceptional group whose artistic achievements shattered the conventions of the time: a very recent exhibition, “Je Déclare vivre de mon art” (2023) at the Fragonard Museum in Grasse, has been dedicated to them, valid in demolishing many prejudices about women artists of the revolutionary period.

One had to reach the Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker (London) booth to find the rare work of a sculptor, aristocrat Anne Seymour Damer (1748-1828), with her Peniston Lamb in the guise of Mercury (exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1787). The small bust, in Carrara marble, portrays the 15-year-old son of a close friend of the author, the famous Elizabeth Lamb, Viscountess Melbourne, a leading figure in the social and political life of her time. Peniston is portrayed with an old-fashioned taste that, with its severe symmetry and stylization of the eyes, reflects the experiences in Italy of Anne Damer, a pupil of Ceracchi and Bacon. Young Lamb, destined for a political career, died prematurely (1805), leaving the field to his younger brother William, prime minister of the United Kingdom in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign.

A less noble, but certainly more seductive, aura radiates Juana Romani’s (1891) Magdalene (1867-1923), proposed by Jean-François Heim (Basel); a model and painter, an absolute protagonist of belle époque Paris, Juana had been born in Velletri as Giovanna Carolina Carlesimo, and had reached France following her musician stepfather. This sulfurous Magdalene, to a good extent an idealized self-portrait, is at the antipodes of the usual representations of the penitent saint, and is part of that strand of sexualization of biblical figures, dear to late 20th-century symbolism, which had its consecration with Oscar Wilde’s Salome. A strongly sensual representation that posed a challenge to common morality, proposing a questioning of the traditional role assigned to women through a celebration of sexual freedom.

Gender issues became universal with Why be born a slave(Pourquoi naître esclave - 1868), by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875), an abolitionist manifesto exhibited by Stuart Lochhead Sculpture (London): originated as a sketch for the Fountain of the Four Parts of the World, in Paris (as a representation ofAfrica), the bust is known in many versions, in bronze, marble and other materials, and was reproduced several times even after the author’s passing. This terracotta, however, although small in size, stands out for its very high autograph quality, and impresses with expressive force. A note of merit for the small thematic exhibition A Room Full of Color, in which Carpeaux’s work was included, designed with the intention of celebrating the mixture of techniques, styles and skills of the artists who worked on the border between sculpture and decorative arts during the 19th century.

Among the most interesting new works, in the field of sculpture, is the marble portrait of Pietro Leopoldo I Grand Duke of Tuscany (1777), brought to the exhibition by Walter Padovani (Milan): the work of a little-known artist from Carrara, Domenico Andrea Pelliccia (1736-1822), the bust, with its haughty manner mitigated by the deeply human gaze, well delineates the image of a modern and enlightened ruler as Pietro Leopoldo appeared in the eyes of his contemporaries. A realization of great executive refinement where the meticulous attention to the definition of details in no way limits the inner presence of the portrait, albeit constrained by a frozen, suspended and ineffable expression. A pupil of Giovanni Antonio Cybei and professor of sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara, Pelliccia is mostly known for the monument to the Grand Duke himself for the Lazzaretto di San Leopoldo in Livorno (1776, today Piazza San Jacopo), and this new addition constitutes a fundamentally important piece in the reconstruction, and full understanding, of his artistic journey. a significant addition to the iconography of one of Europe’s most celebrated rulers, and of his extraordinary reforming will. An image of great immediacy that fits perfectly into the season of official court portraiture, representing that minority current, of French inspiration and Carrarese production, destined soon to give way to the Roman and austere language of Innocent Spinazzi. A significant addition to the iconography of one of Europe’s most celebrated sovereigns, and of his extraordinary will to reform, for which one can only hope that it will enter a public collection.

The large canvas with the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine de’ Ricci by Pierre Subleyras (1699-1749), on the other hand, is a well-known work but has remained almost inaccessible until now, kept in the Roman rooms of Palazzo Sacchetti. Executed for Pope Benedict XIV in 1746, the painting was intended to celebrate the canonization of the Florentine saint, and depicts her vision she had on Easter Day 1542. The hope, again, is for it to be purchased by a museum; however, the work, featured in the Benappi (London) stand, is notified and will not be allowed to leave Italy.

Among other works of Italian provenance, it is impossible not to mention the Saints Lucy and Catherine of Alexandria by Bernardo Daddi (1290-1348); exhibited by Galerie Brimo De Laroussilhe (Paris), the panel comes from the predella of the polyptych of San Giorgio in Ruballa (Bagno a Ripoli), Daddi’s last work, completed in 1348 a few months before his death from the Black Death. Removed from its location in the first half of the nineteenth century, the polyptych (with the Crucifixion and Saints) is now at the Courtauld Institute in London, where the main part is preserved, while the predella is scattered among various private collections and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Strasbourg.

No less interesting is the Saint John the Baptist by Tino di Camaino (1285-1336), on view at Daniel Katz Gallery (London): originating from the Abbey of the Holy Trinity in Cava dei Tirreni, and dating from the central phase of the sculptor’s activity (ca. 1330), the relief remained unpublished until 2019, and has been read as a challenge to Giotto’s painting, with its chiaroscuro effects and softness of modeling, united by a finish capable of suggesting alabastrine transparencies.

Also freshly published (2023) was the precious terracotta with St. Philip Neri (circa 1772) by Giuseppe Sanmartino (1720-1793), a model of the marble statue for the Cappellone di San Cataldo in Taranto Cathedral, whose image flanked the work, in the Kunsthandel Mehringer (Munich) booth, allowing us to verify not only its relevance but also its great vividness.

Also from the Italian sphere were the two very fine marble half-busts, depicting a Satyr and a Satyr with adolescent features, offered by Tomasso (Leeds/London); the pair of sculptures, unpublished but with an important provenance (Baron Mayer de Rothschild at Mentmore Towers), is distinguished by workmanship of great elegance, and a very fine taste in revisiting pagan antiquity. After some discussion among specialists, the busts were displayed with attribution, on stylistic grounds, to the Roman sculptor Alessandro Rondoni (c. 1644-1710), a member of a family active for generations in the restoration of ancient sculpture, and a figure awaiting a rightful rediscovery.

The experience at TEFAF, at the end of the day, must also know how to be light, indulging in aimless wandering to be captured by unexpected works that can open surprising glimpses: approaching the standoff at Gallery 19C (Dallas/Fort Worth) to discover that The Tub (1888) so close to a Cabanel work, is instead by student Henri Gervex (1852-1929) and depicts Valtesse de la Bigne, from whose figure Zola was inspired for the novella Nana. Thus we happen to witness a curious little joke at Agnews Gallery (London), where a naïve visitor asks the price for Lawrence Alma-Tadema ’s (1836-1912) lavish Bacchanal, not holding back an audible expression of surprise at the not modest request of six million dollars. In Daniel Katz’s booth, one may instead end up glossing over a Canova that smacks of the familiar, and be enchanted by the refinement of the terracotta bas-reliefs by Joseph Chinard (1756-1813) and Clodion (1738-1814), while at Stair Santy (London), one can evoke the French Revolutionary Army’s unsuccessful naval expedition to liberate Ireland, thanks to Louis-Philippe Crépin ’s (1772-1851) large canvas with View of Brest Harbor at the time of General Hoche’s embarkation . .. (1798).

In a somewhat defiladed position, but deserving of attention, is the Showcase section, which since 2008 has hosted galleries that have been active on the market for less than a decade: interesting, among the proposals of Cavagnis Lacerenza Fine Art (Milan), is the terracotta model for the Bacchus and Ariadne group (c. 1710) by the Florentine Giuseppe Piamontini (1663-1744). Lastly, among the works selected by Flavio Gianassi, a Tuscan by birth but a gallery owner in London, were panels with Saints Simon, Ranieri, Ambrose and Peter (1378) by the late 14th-century painter Cecco di Pietro, from the church of San Francesco in Pisa and part of a polyptych centered on the Madonna and Child now in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen.

At the end of such an intense day, one cannot hide a certain bewilderment; at the moment of saying goodbye one can feel somewhat dazed, and it happens that you do not know how to answer the question of a gallerist friend who asks you what has struck your imagination the most. As you reluctantly reach the exit, lending yourself to the ritual photos with Tom Postma’s flowers, you rely on your notes, and on the photographs you have taken, to tidy up your thoughts for the next few days, wishing, as in a superstitious ritual, that you will be able to return next year, perhaps staying longer.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.