Reportage from Modenantiquaria 2025: our selection of the most interesting works (with prices)

Modenantiquaria is one of the most important events in the Italian and international antiques scene, and the 2025 edition, running from Feb. 8 to 16, will not disappoint the expectations of enthusiasts and experts in the field. The fair, held every year at Modena Fiere, saw this year an attendance of artworks and collectibles as always of great value. For those who love art and antiques, Modenantiquaria represents an important opportunity to admire and purchase objects that tell the story of our culture, from painting and sculpture to vintage furniture and design objects. But it is not only aesthetic beauty that captures the attention: the fair is also a privileged window to discover how varied and fascinating the antiques market can be, which every year offers works by unknown masters, but also true rarities that risk escaping historical memory if not carefully preserved.

In this edition, we have selected some of the most interesting works, with special attention to those that tell the soul and history of Emilia. Indeed, the art of Emilia, the focus of Modenantiquaria, is a universe rich in artistic traditions and influences ranging from the Renaissance to the Baroque, but also from modern techniques to contemporary art. Each work presented at the fair has its own history and appeal. The Finestre Sull’Arte selection seeks to highlight not only the historical importance of the works, but also the variety and richness of the pieces. Here then is our selection, always, as per our tradition, with prices of the works.

1. Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, Madonna and Child with Saints known as Pala Tacoli (c. 1490; tempera on canvas, 224 x 138 cm). Request: 800,000 euros. Presented by: Cantore Antique Gallery

Arguably the most expensive work at the fair, presented by Cantore Galleria Antiquaria, is one of the most important pieces of 15th-century Emilia still in private hands: it is the Pala Tacoli (or Pala Grossi) by Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (documented in Bologna, Parma and Reggio Emilia from 1487 to 1518), an Emilian painter with the same name as the more famous Piedmontese Renaissance painter nicknamed “the Sodom.” The painting comes from the destroyed Oratory of the Conception of the Blessed Virgin in Reggio Emilia: it is known as the “Grossi Altarpiece” since it was formerly owned by the family of the same name, which bought it in 1960, but it is more correct to call it the “Tacoli Altarpiece” since it is believed that the commissioner was the Reggio Emilia nobleman Ludovico Tacoli, who held the patronage of the church of San Giacomo, also destroyed, near the Oratory of the Conception. The work is one of the rare examples of this elusive painter, who reveals obvious debts to the Ferrara painting of Ercole de’ Roberti and Francesco del Cossa. The work was definitively attributed to Bazzi in 2014 by scholar Antonio Buitoni, who compared the Tacoli Altarpiece with two frescoes in San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma bearing the artist’s signature.

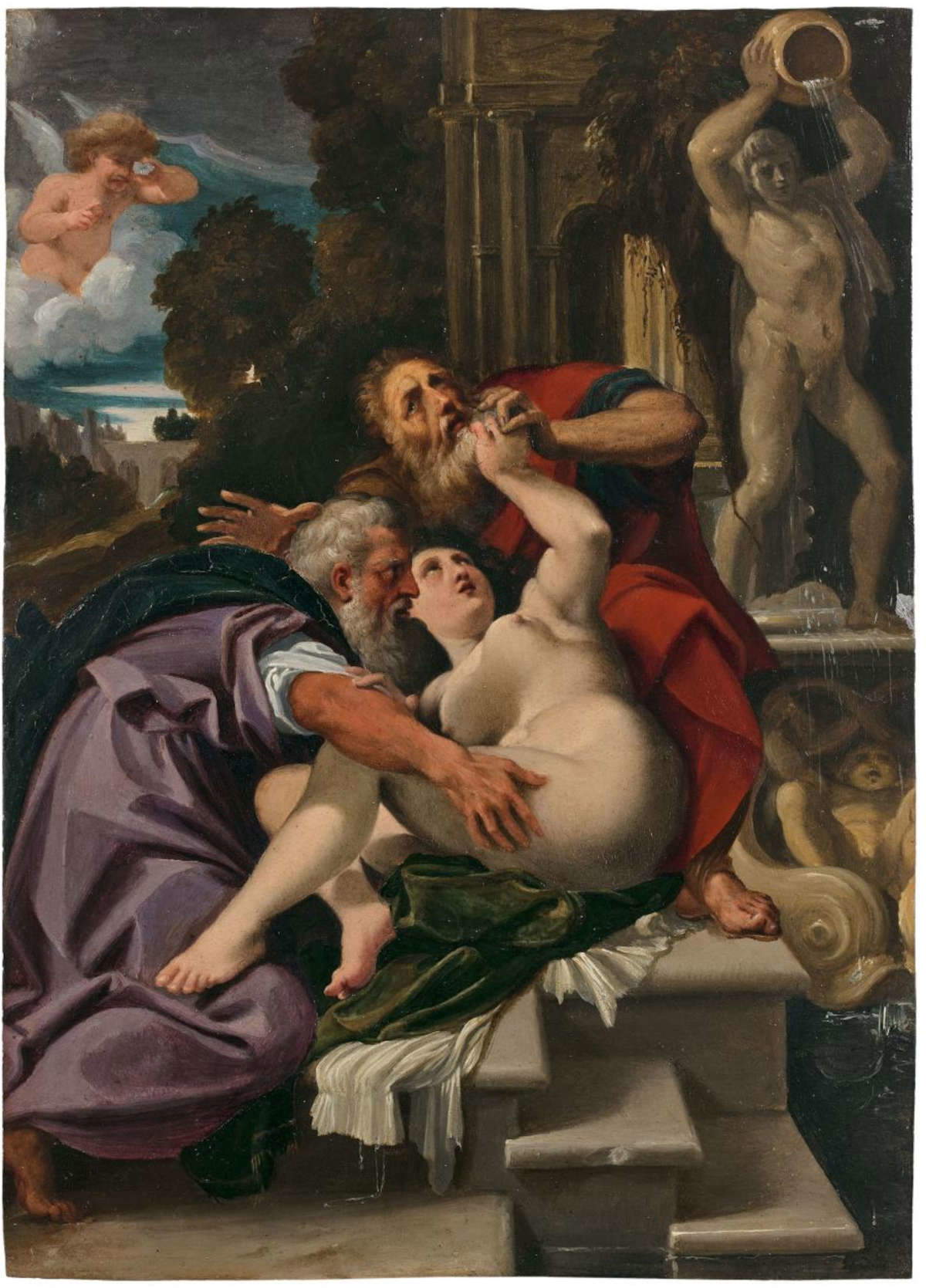

2. Ludovico Carracci, Susanna and the Old Men (oil on copper, 34 x 24 cm). Request: 160,000 euros. Presented by: The Two Towers

This is a scaled-down replica of the large canvas by Ludovico Carracci (Bologna, 1555 - 1619) now in the collection of BPER Banca. The latter was attributed to Carracci by Carlo Volpe: according to the scholar, it is the painting that Carlo Cesare Malvasia, in his Felsina pittrice, reported having seen in 1678 “in Venice in the Vidman house.” The painting, depicting the biblical story of Susanna, was intended from the beginning for private devotion, and is characterized by powerful drama and sensuality. The scene, which depicts the two old judges’ undermining of Susanna in the garden, is executed with a realism that highlights the sensuality of the young woman’s body, the object of the two old men’s lusts, but also contrasts with the woman’s shame and pain. Susanna’s position, with her exposed nudity and defensive gesture, emphasizes the conflict between the two old men’s desire and the girl’s resistance. However, the moralizing intent is evident in the choice to accentuate the violent aspect of the scene to emphasize the lesson of virtue that Susanna’s story conveys, a message that is also reinforced through the presence of the weeping angel. Moreover, the reference to Michelangelo’s pose of Susanna, similar to the Sistine Chapel’s Eve, shows a clear stylistic borrowing from Michelangelo.

3. Carlo Bononi, The Genius of the Arts (1621-1622; oil on canvas, 120.5 x 101 cm). Request: 150,000 euros. Submitted by: Goldfinch Fine Arts

Among the most important works in the production of Carlo Bononi (Ferrara, 1569 - 1632), The Genius of the Arts, also placed on the cover of the major exhibition on the Ferrara artist held in 2018 at Palazzo dei Diamanti, is rendered in the image of a winged young man with a laurel-crowned head arranging another laurel wreath on a number of objects, namely a stringed instrument (probably a viola), a book, the head of a bust, a palette, a lute, a trombone, a music book, a square and a compass. All of which allow the figure to be identified as the Genius of the Arts who protects and exalts the mechanical and liberal arts. Attributed to Bononi as early as the 1960s by Hermann Voss, it bears clear Caravaggesque influences and can therefore be dated to a period following Bononi’s alleged stay in Rome. “A masterpiece,” Giovanni Sassu called it, “worthy to rival in sensuality the other known derivations from the Caravaggesque prototype,” namely the Amor vincit omnia now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

4. Michelangelo Anselmi, Madonna and Child, St. Catherine and St. Clare (c. 1530; oil on panel, 39.8 x 35.7 cm). Request: 150,000 euros. Submitted by: Carlo Orsi Gallery

Michelangelo Anselmi (Parma, 1492 - Lucca, 1554) was one of the most refined and distinguished artists of early 16th-century Parma. His work is characterized by a fusion of styles, initially influenced by Correggio and Roman painting, and later enriched by contact with Parmigianino. The period after the early 1920s, in which Anselmi’s pictorial language became more complex, includes the small panel brought to Modenantiquaria by Carlo Orsi, which testifies to his move toward a more mature and sophisticated phase of his art, especially after Parmigianino’s return to Emilia following the Sack of Rome. The painting in question has been documented since the mid-nineteenth century, when it was reported in the collection of Sir Francis Baring, first Baron of Northbrook, a member of the famous English banking dynasty. At this stage, Anselmi’s painting is marked by a grace and stylistic refinement that place him among the leading exponents of the Emilian Renaissance, alongside Correggio and Parmigianino. His art reflects the elegance and finesse of the highest artistic trends of the time, while still maintaining a strong connection with local tradition and its evolution.

5. Giovanni Baglione, The Trinity crowns the Virgin in the presence of angels, saints, and figures from limbo (oil on canvas, 95 x 135 cm). Request: 120,000 euros. Presented by: Giusti Antichità

The Giusti Antichità gallery in Formigine presents an interesting unpublished work by Giovanni Baglione at Modenantiquaria. The painting is an oil model anticipating an apsidal fresco, probably intended for an important church. The scene, symmetrical and solemn, depicts the Virgin crowned by Christ, with the Eternal Father blessing the act. Several figures populate the work: there are, for example, Adam and Eve in the foreground, Noah raising the ark, his wife Naaman, in short, several characters from the Old and New Testaments, with the Virgin acting as a link between the two world times. According to the scholar Massimo Pulini, who has studied the painting, “such an unfolding of presences will prove useful in finding the primal destination of this model, which I believe was executed, and cleverly invented, by Giovanni Baglione, an important Roman artist, Caravaggio’s rival (at least in the famous lawsuit he brought against Merisi in 1603) and biographer of many artists working as he did in Rome in the early seventeenth century.” In his opinion, “we are faced with a generous expenditure of ideas that allows us to understand the importance of the commission, and the work contains, admirably, twenty paintings in one canvas, surely the result of many drawings and individual studies that allowed the author to approach the task with great elegance and professionalism. In the list of works dispersed or destroyed along with the building that housed them, there is no mention of this subject, but we know that Baglione produced altarpieces with a similar theme or with a story featuring an Immaculate Conception as the protagonist.” The work can be dated to the late 1720s and is related to other similar creations by the artist, such as paintings in the Capitoline Museums, Palazzo Sorbello in Perugia and Gravedona. The inventory number visible on the canvas suggests a provenance from a prestigious Roman collection, perhaps Barberini or Colonna. The attribution is confirmed by Baglione scholar Michele Nicolaci.

6. Giuseppe Molteni, Portrait of a Noblewoman (1835-1840; oil on canvas, 234 x 172 cm). Request: 100-150,000 euros. Submitted by: Fallavena

This portrait, recognized as the work of Giuseppe Molteni (one of the greatest portrait painters of the 19th century) by scholars such as Fernando Mazzocca and Fabio Massaccesi, depicts a woman elegantly portrayed in the living room of her home. The light, filtering through a window partially concealed by a heavy curtain with iridescent golden reflections, illuminates her with a theatrical effect, as if she were on a stage. The lady is comfortably seated on a sofa covered in gold brocade, embellished with green tassels, while with her left hand, covered by a glove, she brushes her chin and rests her elbow naturally on a small oval wooden table. The latter, featuring a marble top and a foot decorated in the Empire taste with female caryatids, festoons and brass lion heads, also houses a lamp and a vase of flowers, among which delicate blue bellflowers stand out. A luxurious fur manteau has been carelessly left on it. With a tilted face and a smiling expression, the woman turns her gaze directly to the viewer, appearing perfectly at ease in the intimate elegance of her bourgeois abode, refined but devoid of ostentation. The work presented by Fallavena has a monumental slant, but this does not prevent Molteni from dwelling on the meticulous rendering of materials and objects-from furniture to textiles to flowers-giving a glimpse of the technical skill honed over years of academic study. A distinctive detail is the turban worn by the protagonist, an exotic accessory that Molteni uses in many of his works, such as in the Portrait of Eugenia Attendolo Bolognini Vimercati Sanseverino (Sant’Angelo Lodigiano, Attendolo Bolognini Castle), the biblical Rebecca (Milan, Poldi Pezzoli Museum) and the more evocative Slave in the Harem (private collection). The dating of the painting can be placed around the 1830s, finding parallels, according to Fabio Massaccesi, in comparisons with works such as the Half-length Portrait of Maria Luigia (private collection) and the Portrait of Rosina Poldi Pezzoli (Milan, Trivulzio collection).

7. Adriatic-area artist, Slab with small arches and animals (late 13th century; Istrian stone). Request: approx. 100,000 euros Submitted by: Santa Barbara Art Gallery.

Just re-emerging on the market, and therefore still to be studied, is this slab with bows and animals, from the Adriatic area, made of Istrian stone. The decoration that this slab (probably originally placed to decorate a baptismal font or a transenna inside a house of worship) is indeed compatible with the productions of Dalmatia, Istria, and the upper Adriatic in general in the thirteenth century. Below the palms face pairs of peacocks, animals that allude to the resurrection of Christ and recur frequently in early medieval decorations: indeed, it was an ancient belief that peacock flesh was incorruptible. The depiction of facing pairs while drinking from a cup, the cup of immortality, is another common element in this type of object.

8. Simone Cantarini, Saint John the Baptist (oil on canvas, 70 x 52 cm). Request: 95,000 euros. Presented by: Altomani & Sons

The St. John the Baptist by Simone Cantarini (Pesaro, 1612 - Verona, 1648) presented by Altomani & Sons has in the past been the subject of studies by Massimo Pulini, who traced the work back to the Pesaro painter’s activity. The painting was also shown in an exhibition in Rimini in 2013 (the work was also reproduced on the catalog cover). The Young Baptist was a subject often frequented by Simone Cantarini: moreover, a preparatory pencil drawing of the work is also preserved at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. The painting was formerly attributed to the Tuscan Ottavio Vannini: “The clarity of the surfaces and the epidermal turning of the Saint John the Baptist actually lend themselves to confusion with the tempered naturalism of the Tuscan painter,” Pulini wrote, “but that much of serene classicism contained in it has a Bolognese air and dialogues more closely with the formal squareness of the works of Michele Desubleo. Listened to from life, the work intones one of the most limpid voices used by Cantarini, polished and polite, almost tenor-like, but if the eloquence of the pictorial face superimposed on the graphic one were not enough, look for the insistent echo, among Simone’s images, of the pose of the Baptist. There are many instances where the artist uses the same arm, the same hand clasping the thumb at the joint of the index finger.”

9. Bastiano da Sangallo known as Aristotile, Holy Family with St. John (oil on panel, 70 x 101 cm). Request: 34,000 euros. Submitted by: Ars Antiqua

This painting, presented by Ars Antiqua, is given by Alessandro Delpriori to Bastiano da Sangallo, also known as Aristotile (Florence, 1481 - 1551). Until this new insight, the work was attributed to an anonymous Florentine master, called “Master of the Lamentation of Scandicci.” because of its affinity to works such as the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the church of San Bartolomeo in Scandicci. Bastiano da Sangallo, grandson of the famous Giuliano and Antonio da Sangallo, is known for his multifaceted career as an architect, stage designer and painter. He was a pupil of Perugino and Michelangelo, and his career took him to Rome and then to Florence, where he made a notable impact on the theatrical and architectural scene, including his work at the Rocca Paolina in Perugia and the building site of Palazzo Pandolfini in Florence. His painting, however, showed a lively participation in the Florentine artistic directions of the time, including influences from Raphael and Andrea del Sarto. In the painting, which shows the Virgin and Child with St. John the Baptist as a child, the gentleness of form typical of the late 15th century is still evident, but it is enriched by a more complex relationship between figures and space, which is influenced by Michelangelo and Raphael’s early work. The use of shadow on the faces, foreshadowing the Passion, and the focus on portraiture give the figures an emotional depth and a symbolic dimension that are signs of the artist’s stylistic maturity.

10. Alfonso Lombardi, Penitent Saint Jerome (1522-1525; terracotta, 48 x 33 x 20 cm). Request: 90,000 euros. Submitted by: Ossimoro Art Gallery.

The beautiful terracotta by Alfonso Lombardi (Ferrara, 1497 - Bologna, 1537) presented at Ossimoro’s booth is described by scholar David Lucidi as an “unpublished and precious testimony of a working parenthesis of the famous Emilian sculptor in the territory of Faenza between 1520 and 1530.” The work comes from the collection of the villa of the counts Morsiani in Bagnara di Romagna, one of the oldest noble families in the region. The sculpture shows a remarkable resemblance to a similar St. Jerome in Castel Bolognese and has a regular cut at the base of the belly, a typical technique in clay statuary to facilitate firing and mounting. This suggests that the work was originally part of a full-length statue, probably placed in a niche or inserted into an altarpiece. The sculpture was not designed for a full view on each side, as evidenced by the hollowed-out back molded in high relief. The execution technique employed, with the use of an ephemeral core and holes for firing, is typical of the Renaissance and is described by Baldinucci. Some more delicate parts, such as the left arm missing today, may have been modeled separately and added later. The work shows distinctive features of the style of Alfonso Lombardi, who was known to reuse physiognomic and anatomical models in multiple works. Indeed, the face of the Saint Jerome shows strong similarities to other figures of his, such as the Apostle of the Virgin’s Transit and the Saint Roch of Faenza. This practice is confirmed by the inventory of Lombardi’s workshop, which kept several terracotta heads at his death, probably prototypes intended for replication in different compositions.

11. Louis Dorigny, Danae (oil on canvas, 151 x 236 cm). Request: 40,000 euros. Submitted by: Fondantico by Tiziana Sassoli

Louis Dorigny (Paris, 1654 - Verona, 1742), a French painter active between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was a major player in Baroque decoration, especially in the Veneto region. Born into a family of artists, he trained in Paris at Charles Le Brun’s Academy before moving to Rome in 1672, where he studied the great Baroque cycles, influenced in particular by Giovan Battista Gaulli (Baciccio). After traveling between Umbria and Romagna, he settled in Venice in 1677 and then in Verona from 1690, also working in Padua, Vicenza, Treviso, Udine, and Vienna. His early style was influenced by Venetian tenebrous painting, but he soon moved toward an elegant classicism, evident in his Verona works for the chapel of the Collegio dei Notai (such as the 1697 Annunciation). In the early eighteenth century, his painting became more abstract and decorative, as evidenced by The Gathering of the Manna in the Desert (1704) painted for the church of San Luca in Verona. The Danae presented by Fondantico, comparable precisely to The Gathering, shows the influence of Titian, Michelangelo, and Tintoretto. According to Pietro Di Natale, who has studied this work, the Danae was probably intended for a wall of a large salon, and is an important addition to the catalog of Dorigny, recognized as one of the finest Baroque decorators and the most influential French painter in Venice at the time.

12. Mario De Maria: La Luna batte sulle cancrene dei muri (1906; oil on canvas, 56 x 73.5 cm). Request: 50,000 euros. Submitted by: Edoardo Battistini’s Fin de Siècle.

Recent star of the monographic exhibition on Mario De Maria, aka “Marius Pictor” (Bologna, 1852 - 1924), held at the Museo Ottocento Bologna, La Luna batte sulle cancrene dei muri is one of the greatest masterpieces in the production of this singular artist in love with the moon, the protagonist of many of his most interesting and recognizable compositions, and also in love with Venice, where the canvas is set (the work is in fact also known as Serenade in Venice). The work is signed and dated “Venice, 1906.”

13. Giacomo De Maria, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1890s; polychrome terracotta, 65 x 100 x 55 cm). Request: 38,000 euros. Submitted by: Iotti Antiquities

Recently resurfaced on the antiques market, this Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Giacomo De Maria (Bologna, 1762 - 1838), in excellent condition, a singular neoclassical terracotta sculpture, is composed in a single block, formed by a clay platform supported by a wooden tray, on which the six figures unfold: the dead Christ in the center, Joseph of Arimathea (or Nicodemus) supporting him, the Virgin mourning her son, Mary Magdalene, and two fifth putti holding two instruments of passion, namely the sponge and the spear. The work in ancient times was perhaps contained in a scarab or glass case and was probably located in an aristocratic residence, presumably in a domestic chapel or at any rate above a small altar or niche. According to Andrea Bacchi and Davide Lipari, who have studied the work, this Lamentation can be juxtaposed with similar compositions, from the 1780s and 1890s, found in the shrine of the Blessed Virgin of San Luca in Bologna and in the church of San Bartolomeo in Bondanello, traced by Antonella Mampieri to De Maria himself. The composition, Bacchi and Lipari write, is predominated by elements such as the “perpendicular lines, the emotional control of the characters, and the old-fashioned treatment of hairstyles and beards.” All features that “betray the arrival in Bologna of neoclassical taste and testify to De Maria’s Roman training experience, which took place between September 1786 and August 1787, thanks to which he was able to come into contact with the work of Antonio Canova.”

14. Fabio Cipolla, Le modiste (1891; oil on canvas, 112 x 163 cm). Price: 30,000 euros (sold). Submitted by: Paolo Antonacci

The painting by Fabio Cipolla (Rome, 1852 - 1935) presented by Paolo Antonacci (and, moreover, already sold) is a typical work of the production of this late 19th-century artist who specialized in genre painting, preferring everyday subjects. The work, dated 1891 and of which a signed sketch has recently appeared on the Roman antiquarian market, depicts five young women, portrayed in an interior setting as they gather around a table in a lively and cheerful atmosphere. The girls, clearly milliners, are busy adorning ladies’ hats with feathers, bows and flowers, carrying out their work lightheartedly as they converse and smile in their atelier. With extraordinary skill, the artist has depicted them in different poses: some seated, some standing, one seen from behind. On the right side of the painting one notices tall perches on which already completed hats are arranged. The lighting is striking: the dim light filtering through the large window on the right contrasts with the warm glow of a lamp that illuminates the main scene. The young women, with their hair gathered at the nape of their necks, wear clothes typical of late 19th-century fashion: long skirts of dark fabric cinched at the waist by belts and fine shirts with wide sleeves and high collars.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.