Podcasts, audio guides, radio, music: what audio tools for the museum

The pandemic of COVID-19 now seems to be a thing of the past, but if there is one thing museums can safely take as a moral of those unprecedented times, it is the fact that digital matters. Indeed, we might add that the potential that digital holds is clearer now than ever before, but once again it is but one of a wider range of tools to which the 21st century museum has access.

It was against the backdrop of this experience that last April 18 the University of Macerata held a full-day seminar on “Art That Speaks,” convened jointly by Patrizia Dragoni and Cinzia Dal Maso. It was dedicated to Massimo Montella, economist, cultural manager and the mind behind Italy’s leading heritage magazine, Capitale Culturale. Montella’s initiative, which uses radio to promote and disseminate Marche’s cultural heritage currently found in museums outside Italy, was deliberately chosen as the setting for the day’s work. I am among those who firmly believe that Montella’s foresight should be much more celebrated internationally. Hopefully, this recognition will come in a timely manner.

The conference proved to be the right opportunity to present the latest in sound-inspiredand sound-informedprojects. Podcasts took center stage, as expected, but the same can also be said for radio, audioguides, and music.

The continued rediscovery of podcasts by Italian museums, which is, by comparison, a rudimentary technology compared to hi-tech augmented or virtual reality, not to mention radio, suggests a choice that is, on the one hand, informed by cost and budget but, on the other, a proven solution. In addition to museums, the cultural podcast scene now includes the growing phenomenon of The Mona Lisa, in which the narrative is lightened to be consumed by a much wider audience beyond the museum walls. But should podcasts be thought of as an experience to interact with outside the museum? Certainly not.

Podcasts seem to represent the right product that can be easily woven into everyone’s daily routine. We can drive and listen to a podcast. We can do our daily chores with the voice of a podcast but we can also visit a museum and listen to a podcast even though it may not have been created to be specifically used and consumed in a museum. At the end of the day, the projects presented made it clear that it is the technology that matters for museums, rather than choosing the latest hi-tech gadget that might be complex to sustain in the long run. To that end, there is neither new nor old technology. It is the technology that matters that seems to have the upper hand.

Audioguide projects have also received their fair share of attention, and as the seminar organizers rightly pointed out, the audioguide may still have a purpose. Interestingly, audoguides can also be the right tool with which to personify the museum. The tone of voice, choice of character, delivery, and script can represent the very voice of the museum that tells, describes, and makes users visualize the content of the museum. It could also be part of a larger multisensory experience generally based much more on the visual.

We have come to associate audioguides with visually impaired museum audiences as well, and the seminar presented some of the latest projects of Italian museums in this regard. I am one of those who strongly believe that such projects should be made accessible to a wider audience that includes mainstream audiences. This would ensure that the museum’s pursuit of inclusion does not, paradoxically, add up to exclusion.

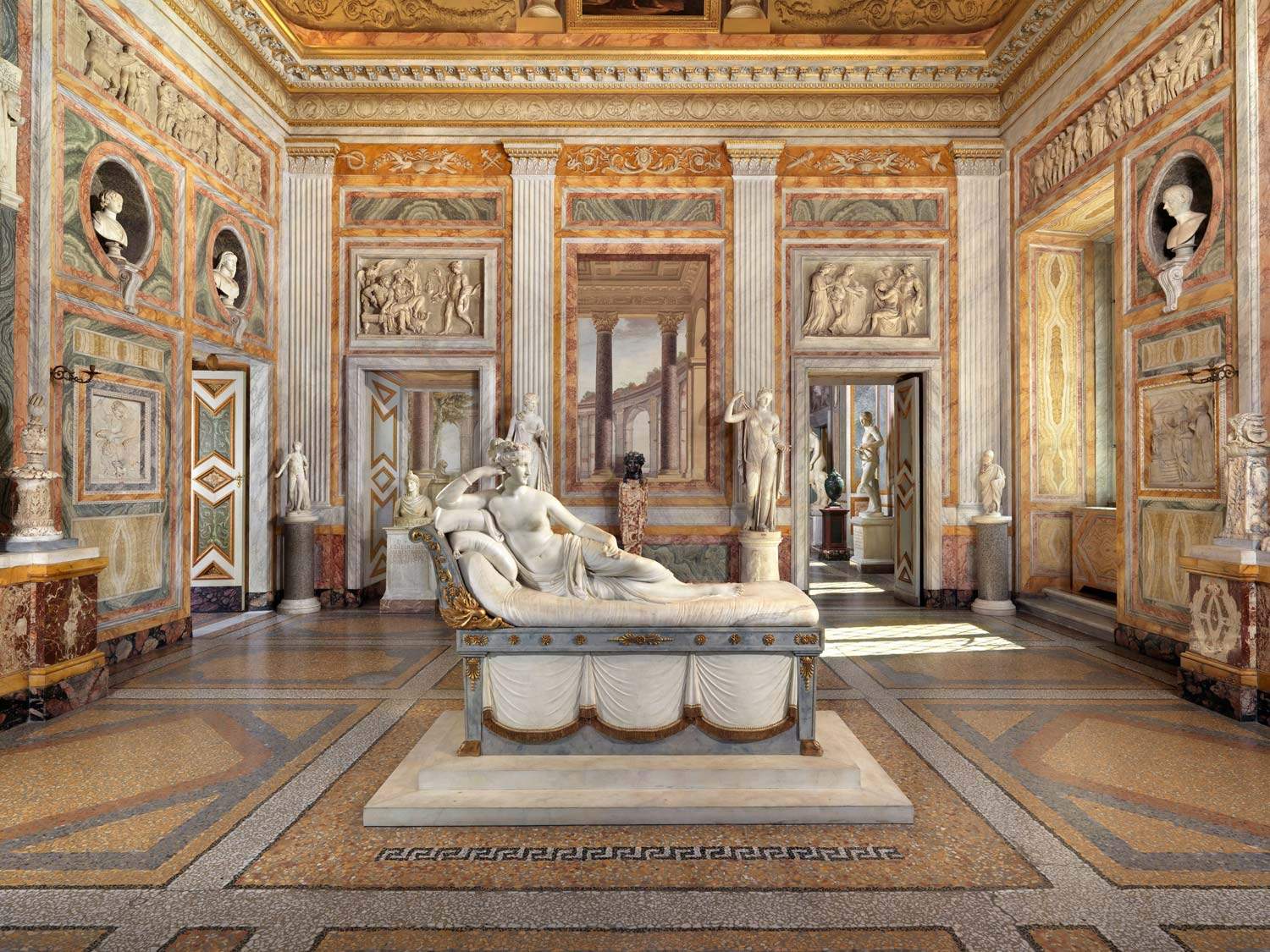

At the end of the day’s proceedings, we were also reminded that the museum will always be as much a sonic space as it is widely recognized as a visual one. The Borghese Gallery project presented at this conference demonstrates this indisputably. Rather than being a space in which to present a musical experience, it is the place itself that can inform, inspire and foster a musical experience dictated by the sense of place and its vibrations. This thought-provoking project about a specially composed musical experience within the space itself should remind us that even though we experience art while viewing, sight still evokes sounds, textures, and taste when our store of knowledge contains clear reference to them. The opportunity lies in better understanding when our store of knowledge is not charged and how to propose and package what can rightly be understood as a lost experience.

The daylong seminar took stock of a situation that, as the organizers rightly pointed out, was not so present and flourishing about a year ago. This in itself is a fitting example of how museums rise to the occasion by engaging with sound, voice and hearing. The underlying challenge is also about how and in what ways sound can be part of a broader and richer experience informed by transmedia thinking in which the digital and the physical, the auditory and the tangible, enable museums to develop new itineraries, ways of engagement and interactivity that are not restricted to the physical space of the museum, which we can rightly see as a container of content, but extends outward and flows back into the physical space. This is also present in some of the projects presented. It could be just the beginning of something much more exciting. Perhaps.

In conclusion, the full-day seminar argued for the next step forward for museums and that is about strategy. The focus could be much more on the ways and means by which sound can be used to provide access to specific museum content, perhaps even in a well-thought-out sequence with the use of a multisensory toolbox in which sound is just one of a wider range of tools the museum has at its disposal. This is where the multiplatform museum might be heading.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.