Parma exults by opening its doors wide again to Correggio

Next September 8, the city of Parma will inaugurate an exceptional and very singular exhibition: an unforgettable Fifth Centenary of Correggio’s creative cycle. Indeed, the “secularia quinta” of the Painter’s extraordinary presence on the Italian art scene with his supreme masterpieces are flowing. Recall that the frescoes in the dome of St. John’s depict Jesus himself descending from heaven at the moment of the Evangelist’s death to greet him directly, and it is a gigantic painting all in foreshortening. About the Fifth Centenaries, the “Friends of Correggio,” active in Antonio Lieto’s hometown, have already celebrated with two fine editions the “Madonna of St. Francis” in 2015 together with various European scholars, and the difficult, albeit beautiful, “Room of St. Paul” in 2018, bestowing on the latter the unpublished unveilings of Renza Bolognesi.

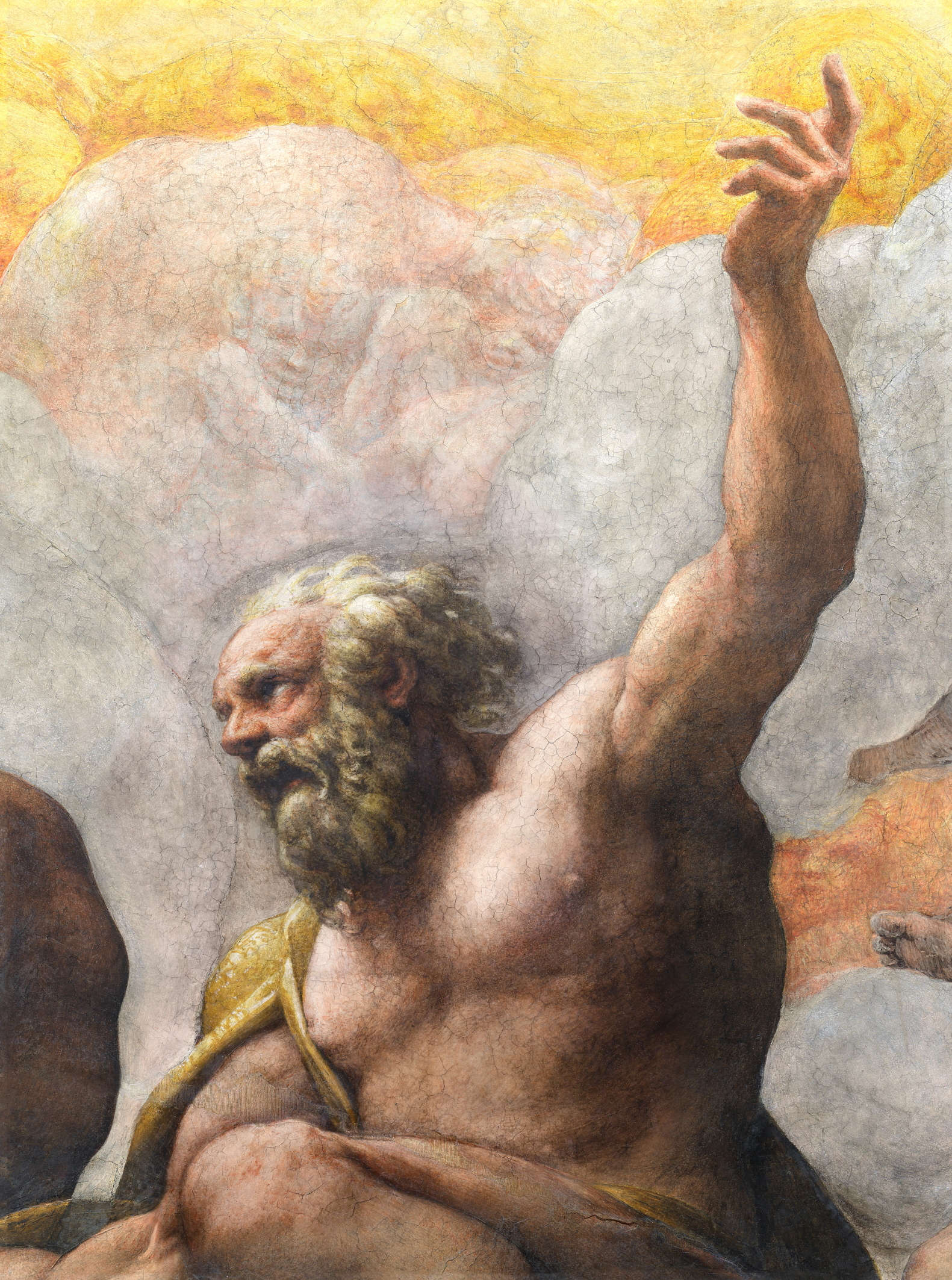

With the celebration of the San Giovanni frescoes now also redeems the very strange silence on Correggio that connoted Parma when it was called “capital of culture.” The backbone of the event is the surprising and masterful photographic contribution of a master, Lucio Rossi, who thus crowns a career of vast and ever-renewing periegetic experiences. Before assessing Rossi’s feat, perhaps not to be forgotten are the fruitful approaches to the marvelous dome that has always attracted attention and questions, along with an articulate and quite remarkable bibliography. We do so with some images.

Out of curiosity many years ago the writer, as a young man, helped an English professor, without asking his name, to arrange several newspapers on the floor under the dome, on which the scholar lay supine, having his assistant then rotate him in circles moving him from his feet: it was evidently a way to “follow” the totality of the vision; years later he helped U.S. professor Geraldine Dunphy Wind lock the image of John astronomically on Dec. 27, his liturgical feast day. But the most curious encounter was that of Bruno Vaghi, a then highly esteemed photographer, who in 1962 at the end of a cycle of restorations was invited to climb inside the dome to shoot it in view of the distinguished volume later realized by Roberto Longhi. His daughter recounted her father’s surprise, and almost his rejection at having to reproduce on the stretched plane of the printed photograph the total curvature of the dome, even in detail. The very attentive Vaghi declared that only continuous sequences could fail to betray Correggio, and he had a barber’s chair brought to the scaffolding, tilting and rotating, from which he then drew-with much emotion-his linked shots. Other photographers followed him, always good and willing, but all within the limit of “contact as is.” We say this to warn that, really, reproductions of the dome need first of all an embricated and inexhaustible capacity for investigation, but then the due inner assimilation of the shooter who places himself in the very soul of the artist, and from there elaborates an imaginative composition, beyond the sensory boundaries. Marzio Dall’Acqua knows something about this when he edited Franco Maria Ricci’s very rich critical volume in 1990. And such a need for assimilation in these times was felt by Lucio Rossi when he came face to face with the incredible “fatherless” Painter(inscrutable, as Cecil Gould called him) who had soared to break through the millennial crust of finite space-that measurable, tangible, orthogonal and perspectival space-to plunge into the cosmic infinitude of the divine empyrean, populated by free spirits and quantum joyous.

In the lap of the supernal cup those Apostles that Giuseppe Verdi so loved balance round and round in a supreme etimasia, on which the figure of the Word descends from the ineffable throne, thus rendering the Truth of the Presence, and where - everywhere - dance the childlike realities that assure the fullness of innocence needed in the heavenly garden. A Correggio, for this reason, with a great, joyful soul, capable of capturing the bursting holiness of the chèrubi and at the same time the mighty stateliness of the apostles, witnesses of Christ.

Lucio fotografo, in the manner of the reversed Columbian quest between East and West, has punctiliously sought here to set up an offer of popular fruition of the lofty masterpiece by doing the reverse of Correggio’s creative path, that is, by returning to the primary elements of the artist’s inner imagination and arranging them in a broad and flat form - paratactic to be sure, but total - so as to achieve participatory and initial immersion for the viewer, thus led to the springing emotion, to the amazement of the composing of a work of art as he could never have imagined before the finished painting. This is our debt to Rossi: a debt that accompanies every visitor when he or she orients himself step by step on that “reductio al piano” that dared to think, and do, such an expert fisherman of the parts of the real as was this Parma Master. He who poured out for a lifetime - and almost over the entire planet - his vocation to the image, and his rovello, never extinguished, brought the interior of the eye back to the visual substance that painting emanated: a fresco painting, swift as the soul’s jostling; peremptory in the celestial totality conceived as an event above time; astonishing in the throw of the motions, and most refined in extending infinitely to the spaces of elevation, tremulous as the breaths from afar.

Perhaps only Correggio could offer such a sideways and so inducing stimulus, in the very city that identifies with him in the world: a city that loves him, that has always admired him, that senses his pictorial freshness, and that intemperate faith that has propelled him so many times into the spiritual afterlife with an energy as simple and immediate as it is incredible: laetentur coeli!!!

In 1520, when Antonio Allegri offered the Benedictine Community of the Monastery of St. John, downtown, the marvelous frescoes of the celestial vault, the painter in his early thirties had already gone through various but limited experiences of depictions suspended in divine pneuma: the covering of Mantegna’s Funeral Chapel gazing on the clouds; the Melozzian visions caught in the 1513 trip to Rome; the precise architectural-biblical attempt at San Benedetto al Polirone; the all-important opening of the heavens in co-presence with the earth in the “Madonna of St. Francis,” and finally that “painting on high” of the Camera di San Paolo where-after the sacrifices and virtues exercised-actual children guaranteed the puerile innocence that total has to be up there, in Paradise.

How did Lucio Rossi technically own the re-transformation of every wheedled part of the painting and bring it back intact - we may say - to a serene enjoyment, so close to the viewer? The analytical answer will come from the exhibition itself (not before the opening) but now we can relate the simple yet prodigious statement of the so cheerfully enamored Lucius: “I want every visitor, every person, to be able for once to walk in the sky!” In this circumnavigation every detail of Correggio’s painting will be captured emotionally, precisely. Here is the enveloping, trembling, ecstatic emotion: to walk in the sky there, in the Benedictine Monks’ great refectory, under the dome but inside the dome, and to perceive in it that sanctifying launch of the hidden St. John that pierces the Apostolic Confraternity and points straight to the heart of Jesus.

So the citizens of Parma have restarted the lofty conversation with Correggio, guided with extreme dedication and limpidity by a well-aware Municipal Administration: by Mayor Michele Guerra, and by Councillor for Culture Lorenzo Lavagetto. The former already in charge of Cultural Assets and Activities for some time; the latter with unreserved enthusiasm in front of the exhibition that essentially revolutionizes the entire ductus of visual retrieval, and that opens in a general sense the use of the most modern tools, accompanied by the restorative guidance of the Master of Images. A big thank you to the abbot and religious of the monastery.

We hope that the catalog will succeed in spreading awareness of the hitherto unforeseeable achievements regarding the proposed execution of the new footage. Lavagetto has made Rossi’s demonstrative science his own, and together the two allies can now well say that the spectacular montage of the Chapter House in the Monastery of St. John is not a photographic exhibition (!), and we repeat: it is not a photographic exhibition, but a true capturing of heaven brought to earth, delivered with admirable simplicity to each of the people; hoping that a series of public conversations may permanently penetrate civic understanding and adherence, especially youth, but also universal consciousness, to the capabilities of reproductive art.

With this, values are accentuated: when reality and truth coincide!

All technical explanations are reserved for the catalog and exhibition times. All images appearing here are by Lucio Rossi, and all rights are reserved by FOTO R.C.R. di Rossi Lucio & C. S.a.s. - Many thanks to Lucio. The exhibition enjoys the commitment of the Culture and Tourism Department of the City of Parma, with support from Fondazione Cariparma and the Emilia Romagna Region, and is hosted by the Benedictine Abbey Community of San Giovanni Evangelista. It will remain open from September 8, 2024 to January 31, 2025. Info: parmawelcome.it

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.