It was an over-seventy-year-old Michelangelo Buonarroti who, roughly between about 1547 and 1555, sculpted the extraordinary Bandini Pietà now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence, one of his most suffered and tormented works, which began at a dramatic time for the artist, since in February 1547 he had lost one of his dearest friends, the poetess Vittoria Colonna, for whom he had drawn a celebrated Pietà, of which a charcoal drawing on paper remains today in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (although we do not know if it was later translated into painting). A few months later, in June, Michelangelo would lose another friend, the great painter Sebastiano del Piombo, and other friends had left Rome, contributing to an increasingly unbearable feeling of isolation in the artist. The drama of Michelangelo’s experience, his torments, his sufferings, his obsessions with the idea of death (the Bandini Pietà was in fact intended for his burial, in the Roman church of Santa Maria Maggiore), are thus poured into this monumental work in white Carrara marble, where the body of Christ, a detail unheard of in similar works for Michelangelo, is supported not only by the Madonna but also by Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus, to whom the artist decides to give his own likeness.

The artist’s burden of disquiet is such that at some point in the work’s history, around 1555, the artist would even attempt to destroy it, albeit in vain. Michelangelo was frustrated, not only by his biographical affairs, but also by the technical difficulties of the work: he had in fact tried to alter the position of Christ’s legs, but because of a vein in the marble the sculptor caused a fracture in the work, and the episode enraged him to the point that he raged against the Pieta by taking a hammer to it. The result was that Jesus’ elbow, chest and shoulder were nicked, as well as Mary’s hand. And the damage was such that Jesus appears today to have mutilated his left leg. Michelangelo would probably have completely shattered it had it not been for the intervention of one of his attendants, Antonio da Casteldurante, who prevented further devastation. Antonio persuaded Michelangelo to give him the fragments, had the sculpture restored by Tiberio Calcagni (to whom the smoothing of Christ’s body and the completion of the figure of Mary Magdalene are attributed), and then sold it to the banker Francesco Bandini (after whom it is named) for the sum of 200 scudi: Bandini placed it in the garden of his Roman villa at Montecavallo. The Pietà remained in the Bandini family’s collections for a century: in 1649, the banker’s heirs sold it to Cardinal Luigi Capponi, who moved it to the Palazzo di Montecitorio in Rome, and after four years to the Palazzo Rusticucci Accoramboni. A further transfer was recorded on July 25, 1671: at that time Piero Capponi, Luigi’s great-grandson, sold it for 300 scudi, through the mediation of the Florentine nobleman Paolo Falconieri, to Cosimo III de’ Medici, grand duke of Tuscany. The Bandini Pietà remained in Rome another three years, since logistical difficulties were encountered on transport, which were resolved in 1674: transported from Rome to Civitavecchia, it was embarked here and reached Livorno by sea, after which it faced another journey on water, across the Arno, to Florence, where it was installed in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, where it remained until 1722. That year, Cosimo III moved it to the back of the high altar of Florence Cathedral, where it remained for more than two hundred years, that is, until 1933, when it was moved to the chapel of Sant’Andrea. Having escaped the destruction of World War II (in anticipation of the bombings it was in fact moved to some storage rooms set up for the occasion), it returned to the chapel in 1949 and remained here until 1981, when it was further moved to its final location: the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, where it is still located today.

The move to the museum’s halls was due to reasons of conservation and expediency: in fact, many tourists went to the cathedral specifically to see it, thus causing problems for worship (and, conversely, during services it was not possible to admire the masterpiece). In addition, it was considered to move it to the museum for safety reasons, since on May 21, 1972, the infamous episode of the damage to the Vatican Pieta occurred, with geologist László Tóth taking a hammer to it with one of his tools of the trade. As of 2015, following major renovations to the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, the public can view the work in the new room titled Michelangelo’s Tribune, set above a plinth that evokes the altar on which it was most likely to have been placed.

“The great artist,” noted Timothy Verdon, director of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, "summarizes in this work half a century of professional experience. In his thirties, he had been commissioned to make the tomb of Pope Julius II in Rome, in his forties the Medici burials. In his seventies and eighties he worked on his tomb, and for this undertaking he worked again on the theme of his first successful masterpiece, the Pietà of St. Peter, sculpted when he was not even twenty-five. And if the youthful interpretation of the theme, despite its elegiac beauty, remains somewhat on a conceptual plane, the work of the elder Michelangelo is on the contrary filled with experience and suffering." The great historiographer Giorgio Vasari thus speaks of Michelangelo’s late masterpiece: “Michelagnolo’s spirit and virtue could not remain without doing something, and since he could not paint, he put himself around a piece of marble to hollow out four round figures greater than ’l vivo, making in that Christ dead for delight and passing time, and as he said, because practicing with the mallet kept him healthy of body. It was this Christ as if deposed from the cross, supported by Our Lady entering under them and helping with an act of strength Niccodemus stopped on his foot and by one of the Marys who helps him, seeing the strength in the mother failed, who overcome by pain cannot hold up; nor can one see a dead body similar to that of Christ, who falling with abandoned limbs makes all attitudes diferent not only of his others, but of those who ever made them: laborious work, rare in a stone and truly divine.”

|

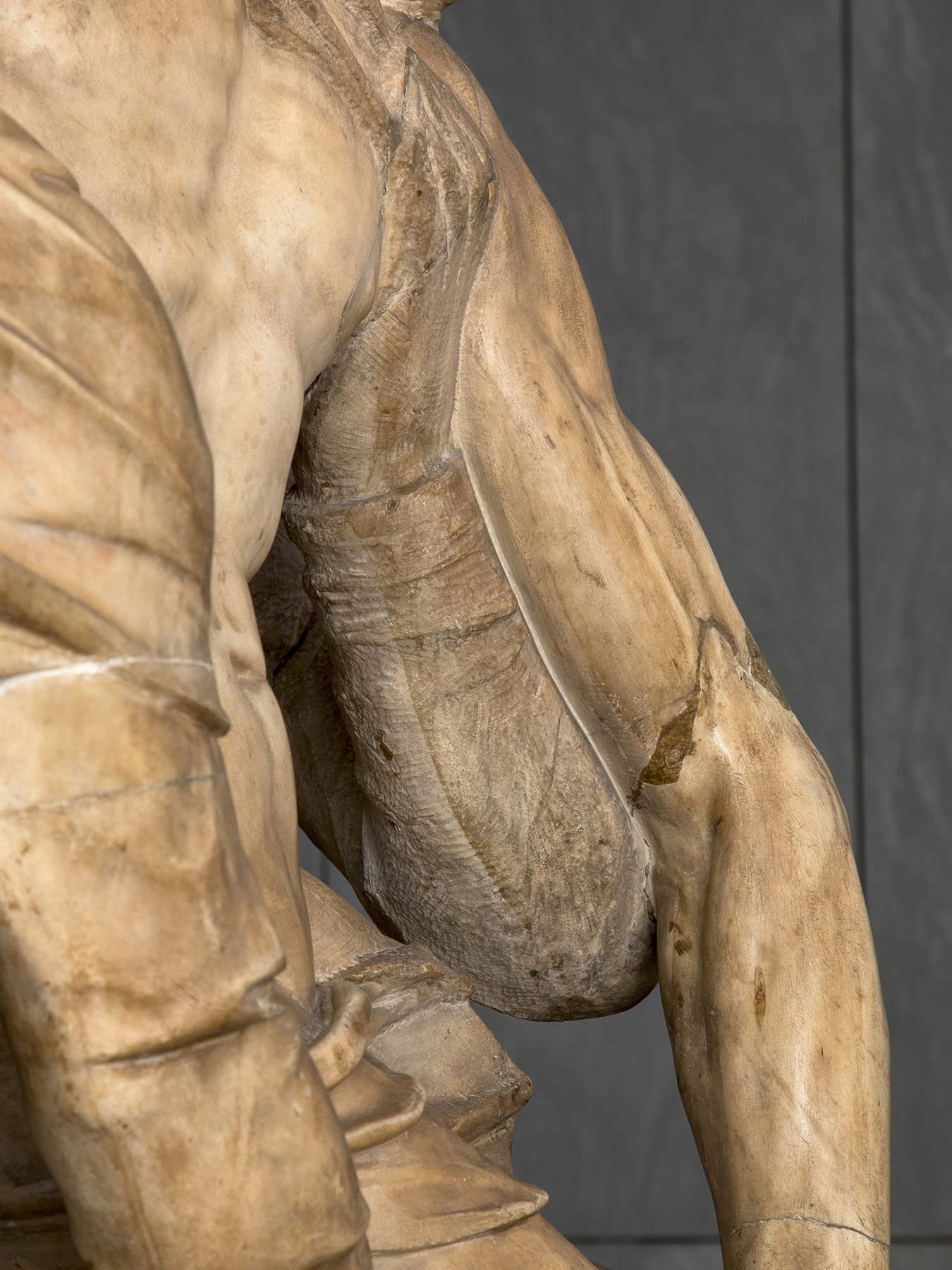

| Michelangelo, Bandini Pietà (c. 1547-1555; Carrara marble, height 226 cm; Florence, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo). Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

On November 23, 2019, a new chapter in the history of the Bandini Pieta opens: the sculpture is in fact to undergo restoration, which is scheduled to be completed in the summer of 2020: however, it will be an intervention visible to the public, which will be able to follow all the operations by observing the restorers at work, thanks to an open worksite specially designed for this purpose, inside the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo itself. The intervention was commissioned by theOperadi Santa Maria del Fiore, received funding from the Friends of Florence Foundation, under the tutelage of the Soprintendenza Architettura, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the metropolitan city of Florence and the provinces of Pistoia and Prato, and was entrusted to Paola Rosa, who will be assisted by a team of professionals trained at theOpificiodelle Pietre Dure and with thirty years of experience on sculptural works by great artists in the history of art, including Michelangelo himself.

Beyond the intervention carried out by Tiberio Calcagni, we do not know of other restorations carried out in historical times, since the sources are silent on the matter. In its almost five hundred years of life, throughout its tormented history, the Pietà Bandini is presumed to have known maintenance interventions, but these are not documented. We know only of a cast made in 1882: the plaster copy is now kept in the Gipsoteca of the Liceo Artistico di Porta Romana in Florence. And because of the substances that were used to make the cast (as well as the very aggressive substances used to remove the residues when the operation was finished), it is likely that the sculptor’s surface experienced an alteration of the original chromatics. Another certain intervention is that which the work underwent after the World War, between 1946 and 1949, when it was subjected to cleaning: we know that it was conducted, but we do not know the results because, again, documentation is lacking. And again, probably in ancient times the sculpture suffered some damage due to an intervention, if in the purchase contract of Cosimo III there is mention of “detached pieces”: it is believed that the work had a restoration intervention, which, however, does not emerge from the documents. Finally, some investigations carried out in the late 1990s by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure and ENEA and published in 2006 in a book edited by Jack Wasserman and titled Michelangelo’s Pieta in Florence, gave evidence of the application of stucco and the existence of three systems of connecting pivots between the integrated and recomposed parts, which suggests interventions carried out at different times and with different techniques.

|

| The restoration site of the Bandini Pietà. Ph. Claudio Giovannini |

|

| The Pietà Bandini restoration site with restorers Paola Rosa and Emanuela Peiretti. Ph. Claudio Giovannini |

|

| The Pietà Bandini restoration site with restorers Paola Rosa and Emanuela Peiretti. Ph. Claudio Giovannini |

|

| The Pietà Bandini restoration site with restorers Paola Rosa and Emanuela Peiretti. Ph. Claudio Giovannini |

|

| The restoration site of the Pietà Bandini. Ph. Claudio Giovannini |

Explaining the reasons for the restoration is Paola Rosa herself in a paper she published in anticipation of the intervention. The Pietà Bandini, says the restorer, "shows all the signs, scars, deposits and patinas acquired artificially and naturally in the span of its almost four hundred and seventy years of life. The traumatic events that occurred at the time of its creation, the collector’s vicissitudes related to the various changes of ownership and the numerous movements it has faced, have inevitably marked and compromised its original facies.“ The intervention, Rosa assures, ”will again offer another important cognitive opportunity. It will be possible to confirm or propose a broader reading of the alteration products and patinas present on the surfaces, with additional results beyond those already achieved in previous investigations. Without entering, at this planning stage, into the merits of the hypotheses concerning the authorship of the various fragments present on the sculptural group, but treasuring the cognitive data already acquired in the past, it is reasonable to pause to observe and evaluate, through careful autopsy examination, the appearance of the surfaces and what they can tell us. The results of the investigations together with all the data collected through timely observation of the problems, related both to the conservative conditions and to the characteristics of the workmanship of the work, will be significant for the identification of the specific methodology of intervention. The approach to the work will be that of a ’minimal’ intervention, aimed at not distorting the vision now established in the collective imagination of an ’amber’ surface. In fact, the image that is to be maintained in any case is that of a sculptural group not in ’black and white’ but subtly modulated and ’colored’ by the varying ’skin’ of the material and by the traces of workmanship, probably already patinated originally in order to achieve harmoniously differentiated effects. This intervention is also intended to recover the majestic three-dimensionality of the work, currently mortified by the dark patinas above it, and instead enhanced in the museum setting that invites the visitor to walk around it. The criterion on which the restoration work is intended to be based is to remove all the superimposed substances that interfere in the reading of the surface, by thickness or chromatic imbalance, lightening without, however, completely eliminating the patinas and patinas with which the work has come down to us. Some surface pathologies, which were once perceived as degradations and therefore totally removed from the surfaces, are now considered historical alterations of the materials and since they are not harmful they have become an integral part for the reading of the work. Therefore, in light of this consideration, what could be identified as calcium oxalate films, as far as possible, should be respected and lightened with caution. The Pieta, now long received in museum settings, is admired by hundreds of thousands of visitors who stop in front of it every year, thus becoming the main factor of degradation. In fact, as they transit in massive flows, people bring with them considerable amounts of dust, atmospheric particulate matter, lint and, when it rains, moisture."

The accumulation of particulate on the surface of the sculpture is deposited differentially in relation to the sculpture’s conformation (also depending on degrees of inclination and processing techniques). There are, Paola Rosa assures us, no conspicuous and inconsistent deposits of dust, but, especially on the back, the Bandini Pietà has congealed due to dust that has infiltrated the porosity of the marble and the spalling, staining the marble deeply. Basically, looking at the work, one has the impression of a work covered and obscured by a thin film that is, however, uneven, due to the variety of sediments that have altered it. All this contributes, Paola Rosa points out, “to undoing the correct reading of the work.”

“This evident chromatic imbalance, in all likelihood,” the specialist continues, “is the consequence of the oxidation of waxes or substances of a protein and oily nature, intentionally applied either at the time of the execution of the integrations with the intention of unifying the chromaticity of the surfaces, or during the execution of casts or probable past maintenance, of which, however, there is no documentation. Over time, these substances that were initially transparent, changing due to their natural aging process, greatly changed the original appearance of the marble, giving it the conspicuous amber tone coloration that we see today. The formation of calcium oxalate films, probably present on part of the marble surface below the most superficial patina, transformed the chromaticity of the original surfaces, assuming a more intense and darker hue on the reliefs subject to dust deposition, and a lighter and brighter one in the deeper grooves of the working tools and on the more polished and polished areas. The visual impact, then, is that of a blurred and deadened chiaroscuro of the surfaces, perhaps different from that intended or intended by Michelangelo ab origine. The research and painterly character that Michelangelo imprinted on his works, through a masterful use of the tools of workmanship in the unfinished areas and of polishing in the areas brought to finish, allowing the marble to absorb and reflect light in a differentiated manner, have been nullified by the substances and deposits that have been superimposed on the surface over time. In addition to the obvious amber coloring, the surface shows spattering, residues of inert matter of various kinds, and slight encrustations on the edge of the base that are most likely the sediments of the original marble block along the faces of the breakage and quarry work. The metal bracket visible on the base was certainly inserted in remote times, both because it has an invasive impact on the sculpture and because it is also present in the copy made in plaster in 1882 and preserved at the Istituto d’Arte di Porta Romana in Florence.” The execution of this cast, as mentioned above, may have left marks on the surface of the marble, including scratches and residues of substances used in the course of operations (partly traced thanks to the diagnostic campaign in the 1990s. Substances that usually leave irreversible stains and halos.

|

| Conservation issues of the Bandini Pietà: color differences on Nicodemus’ left hand highlighted by the vertical line demarcating a lighter area probably cleaned after the cast. Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

|

| Conservation problems of the Bandini Pietà: detail of the tergal part of the work with the very pronounced color differences. Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

|

| Conservation problems of the Bandini Pietà: arm of Christ with the old plaster used for additions, arm of the Virgin Mary with a line showing the points where the pins were used for the 19th-century plaster cast. Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

|

| Conservation problems of the Bandini Pietà: the polished figure of Christ contrasting with the rest of the surface blurred by deposits and color alterations. Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

|

| Conservation problems of the Bandini Pietà: back part of the work where wax had been deposited when the work was on the back of the high altar of the Florence Cathedral. Ph. Credit Alena Fialová |

“The liming operation,” Rosa in fact explains, “in all likelihood imposed the need to carry out a cleaning first and a subsequent patination that, with time, became altered again. The cast exhibited at the Istituto d’Arte also shows a dark yellow coloration, very similar to that found on the marble surface. This suggests that the cast, at the time it was made, was patinated to make it resemble the original as closely as possible.” Finally, the Pieta’s stay, for nearly a hundred years, under a loggia in the garden of the Bandini property in Rome may have affected its state of preservation. “Although protected,” Rosa concludes, “it can be hypothesized that the sculpture has been affected by climatic variations and weathering with the consequent formation of biological patinas on more exposed parts of its surface. At present, it is not possible to verify traces of any previous biological attack phenomena, due to the widespread presence of the patinas and deposits already extensively described. In the arc of its existence, during the numerous changes of ownership, from the prestigious private residences to the last placement in the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and then in the Museum, it is conceivable that the Pietà has nevertheless received various maintenance interventions, even if the current documentary research does not report any trace of it.”

The restoration that will begin in November will, in essence, respect the public’s well-established view of the Pieta’s visibly amber-colored surface and respect the patinas that have transformed the marble’s original coloring over time through their aging process. The restoration, the initial phase of which will involve an extensive diagnostic campaign, aims to improve the reading of the work, which is deadened by the presence of deposits and foreign substances on the marble surfaces of the sculptural group.

For Simona Brandolini d’Adda, president of the Friends of Florence Foundation, which is financially supporting the intervention, it is "a fascinating project that brings us to restore, alongside the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, the Pietà Bandini, a true masterpiece that reflects the tormented soul of Michelangelo’s great genius."

“The works in the new Museum have been the subject of an extensive restoration campaign carried out on the occasion of the opening to the public at the end of 2015,” says the President of the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Luca Bagnoli, "while Michelangelo’s Pieta Bandini, one of the most iconic masterpieces in the collection, remained to be restored. LOpera decided to also initiate this delicate intervention, with the support of the Friends of Florence Foundation, in order to improve the reading of the sculptural group and thus allow the thousands of visitors, who every year choose our monuments, to be able to enjoy this extraordinary masterpiece to the fullest."

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.