by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 29/11/2019

Categories:

News Focus

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

The discovery of the Shadow of San Gimignano, an Etruscan bronze statue from the 3rd century B.C., has finally been revealed: it is one of the most important finds in recent years.

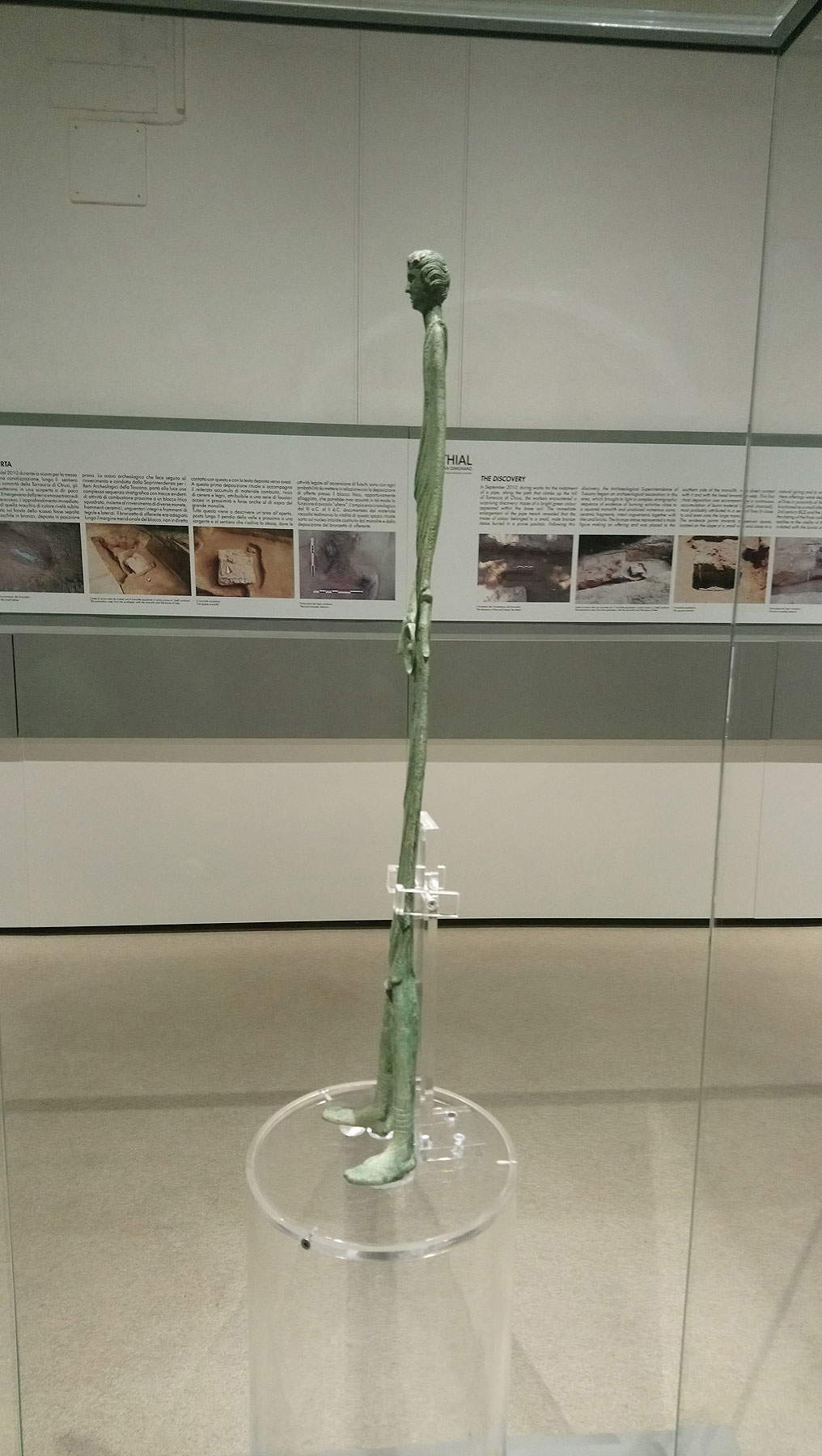

One of the most important discoveries in Etruscan archaeology in recent years has finally been revealed: it is theOmbra di San Gimignano, a marvelous and surprising bronze votive statuette found in 2010 in the territory of San Gimignano (Siena) during some renovation work on a private building near the Fosci stream, among the hills that descend from San Gimignano toward Valdelsa. The statue is on public display for the first time at the San Gimignano Archaeological Museum as part of the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano. The Offerer and Etruscan and Roman Ritual Finds (Nov. 30, 2019 to May 31, 2020).

When it was found in 2010, the bronze statue was buried in the ground: it was workers who noticed its presence when they were carrying out work and noticed traces of a bright green color in the earth. Immediate investigation revealed that there was a bronze male figure there, which had been laid in a prone position. Work was then interrupted to allow the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Siena, Grosseto, and Arezzo to begin the investigation campaign, which was followed by an excavation that revealed a vast open-air Etruscan sacred area, in use for at least five hundred years from the third century B.C. to the second century A.D. The bronze statuette was lying along the southern edge of the block, not in direct contact with it, and with the head laid to the west. It was a ritual deposition.

|

| Etruscan art, Shadow of San Gimignano (first half of the 3rd century BC; bronze, height 64.6 cm; San Gimignano, Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Etruscan art, Shadow of San Gimignano, detail |

|

| Etruscan art, Shadow of San Gimignano, detail |

|

| Etruscan art, Shadow of San Gimignano, detail |

|

| Etruscan Art, Shadow of San Gimignano, detail |

|

| Etruscan art, Shadow of San Gimignano, detail |

The statue in fact lay buried near a squared stone monolith that served as an altar, on which rituals were performed with religious offerings to the local deity; traces of fire exposure were found on the monolith. The sacred area, around which coins, pottery sherds, intact unguentaries and brick fragments were also discovered, was located near a spring: this element could refer to worship for deities related to water and earth. The statue found is that of an offerer and is of the type of the elongated bronzes of the Hellenistic age, similar to the celebrated Evening Shadow of Volterra. The sculpture was recognized as the most elegant in the nucleus of bronzes attested so far. Exactly like the Shadow ofthe Evening, theShadow of San Gimignano also belongs in fact to a serial production: in this case it is a work that presupposes the models of the great plastic of early Hellenism with a reinterpretation of the elongated webbed ex-voto of central-Italic derivation, anchored in forms of the local religious tradition. Similar statues, to which both theShadow of San Gimignano and theShadow of Volterra are related, have also been found in Latium (Nemi), Marche (Ancona) and central-northern Etruria (Orvieto, Chiusi, Perugia, Vetulonia, Volterra and respective territories). Unlike most other specimens, however, theSan Gimignano Shadow has a peculiar importance because of the fact that we know in detail its provenance from a certain context, moreover a sacred one. Moreover, the Sienese statuette stands out for its size: a height of 64.6 centimeters and a weight of 2200 grams.

The statue depicts a standing male figure wearing a toga that reaches down to the calves, leaving the shoulder, right arm, and most of the chest uncovered, while on the feet the offerer wears high laced shoes. The right hand holds an umbilicate patera (found in many Etruscan sculptures, especially in funerary statuary), while the left hand, which adheres to the body, emerges from the mantle with the palm facing outward. The legs are slightly apart and suggest a slight movement to the left, while the facial features, outlined with exceptional naturalism, are well marked, with large highlighted eyes, a pronounced nose, a fleshy mouth, and a centrally dimpled chin. Surprising also is the hair, arranged in wavy locks made with deep furrows that from a back parting move toward the face to cover part of the forehead as well as the ears. If, therefore, theEvening Shadow is depicted nude (it is, in fact, a child figure), theShadow of San Gimignano is clothed in that the character depicted could be a priest.

The artist who created the Ombradi San Gimignano probably came precisely from ancient Volterra(Velathri in Etruscan): the nearby sanctuary of the Torraccia di Chiusi was, after all, one of the boundary places of Volterra’s territory, and the “fauci” from which the name of the Fosci stream derives constituted the entrance to the area under Volterra’s control. The shape of the statue harks back to the models that spread from the third century B.C. onward in central-northern Etruria, where they arrived thanks to circulation within the local workshops of itinerant artisans, mainly from the Tiber area. In fact, the senatorial-type toga and shoehorns (“calcei”) recall the figure of theArringatore, which was probably a large votive bronze depicting a personage in a prayerful attitude and whose clothing was typical of magistrates’ processions in Etruria of the second twenty-five years of the third century BCE. These elements also concur in dating theSan Gimignano Shadow within the middle of the 3rd century BCE.

|

| The area of the discovery of theOmbra di San Gimignano at Torraccia di Chiusi. |

|

| The excavation area of the Ombradi San Gimignano |

|

| The sculpture at the time of its discovery |

|

| The sculpture on display at the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano |

|

| The sculpture on display at the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano |

|

| The sculpture exhibited at the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano |

|

| The sculpture exhibited at the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano |

|

| The sculpture exhibited at the exhibition Hinthial. The Shadow of San Gimignano |

The Shadow ofSan Gimignano was placed at the culmination of an exhibition whose title, Hinthial, is translatable at the same time as “soul” and “sacred” and is conceived as an immersion in the sacred landscape of San Gimignano in Etruscan and Roman times. The exhibition aims to suggest the presence of thecult area in a ritual path that recalls gestures and perceptions of theOfferer: in this way, the curators of the exhibition, Enrico Maria Giuffrè and Jacopo Tabolli, wanted to make this masterpiece re-emerge from its burial by telling of the hopes, prayers and offerings that took place for more than five centuries in this sacred place that was located on the borders of the territories of ancient Volterra in the Hellenistic age.

“The extraodinary nature of this discovery,” Jacopo Tabolli told us, "lies in the fact that there are really very few statues of this kind: the best known is theEvening Shadow of Volterra. The Shadow ofSan Gimignano is another in this series of elongated bronzes that from Tiber models, then from Latium, gradually radiated into Etruria. It is certainly of exceptional workmanship: the artist who made it, in the first half of the third century, follows classical models of the highest level. Of the series of elongated bronzes, this is the only one that comes from even a sacred context, and this gives us an understanding of the function of this exceptionally valuable object. It should also be taken into account that, starting from its deposition, from the second half of the third century, for five hundred years on its burial next to the altar was concentrated the action of first Etruscan and then Roman offerers, so despite the Romanization that was taking place in the area, the latter maintained its own sacred identity that transcended political differences."

As for the finding of theShadow of San Gimignano being an exceptional event, Tabolli argues that “discoveries of this kind are very rare, even though in reality our territory is very rich.” What Tabolli wants to emphasize, however, is another aspect: “it is not important to quantify how many there are and how many could be works of this type,” he concludes, “the important thing is to reiterate how the control of excavation activities is always sudden, because the delicacy of cases like these lies in the fact that the discovery, very often, does not come from a pre-arranged excavation campaign, but from ordinary works. As in the case of this statue: a pipeline is opened, and we often come across something like this, and this calls us to the responsibility of protecting our subsoil, which should be considered as an immense heritage.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.