Has the war made Ukrainian art stronger? Report from a trip to Kiev

Returning by train from Kiev to PrzemyÅ›l and then on to Krakow, on a journey of more than fifteen hours overnight, I keep looking at the Air Raid Alert Map site that shows in real time the regions under risk of attack. It almost seems as if the red alert color follows the train’s path. This is a silly fear, because the chances of a bomb hitting a train traveling through the forest are lower than the chances of being struck by lightning. But seeing the risk represented on a map continues to produce a certain degree of agitation in me.

The situation I found Kiev to be in some ways paradoxical. Alerts are daily and sometimes even missiles still rain down on the capital. Someone as well dies or is injured from time to time, but people seem to pay no attention to it anymore. When the missile alarms sounded, in the week I spent there, I was practically the only one who rushed to the bunkers (which are usually the subway stations), along with schoolchildren, for whom compliance is clearly an inescapable formality. Thus, apart from the fact that the subway stations fill at times with rowdy children, otherwise until midnight, when the curfew begins, Kiev is a city in which life flows normally, in some respects even very lively. Not only are there exhibitions, openings, cultural gatherings, and presentations (the reasons I made this trip), but also the pubs and restaurants are full. The streets are busy, at peak hours clogged. There is also a certain amount of foreigners -- I don’t know whether to call them tourists -- crowding at least the most typical places. Even the wrecks of war are now trophies for visitors. In the center of town, along with a group of Russian tanks and a few missile pieces, there is also an old lady selling Ukrainian flags. It is a sign of how the war is already turning into historical celebration. Especially the advertisements on billboards and posters are shocking: they announce happy times, show luxurious houses and beautiful women. I was not a little surprised to find Forbes in the hotel lobby offered to guests for reading. It is probably a defensive system of the human brain: after a trauma, our mind tends to habituate, to resume the regularity of life.

The trip was organized by Asortymentna Kimnata, Proto Produciia and other organizations thus trying to keep Western interest in Ukraine high. I went, in defiance of fate, along with a scattered handful of European curators and journalists to test a theory: has the war, in Ukraine, empowered art? I know the art situation there quite well, having made many exchanges when I was in Warsaw directing the Zamek Ujazdowski Center for Contemporary Art. I am friends with many artists, and as soon as the war broke out I became concerned about them. I wrote to some, followed their communications on social media. And I must say that the impression I got was that in the first months of the invasion there was an increase in the intensity of their work. There is an example that I think makes what I am saying quite blatant. Lesia Khomenko is an artist who usually paints large monumental figures in a style reminiscent of Soviet paintings and sculptures, those celebrating workers and peasants, such as Vera Mukhina’s monumental The Worker and the Kolkhozian from the 1930s, which later also ended up in the Mostifilm logo and hundreds of stamps. Of course, in Khomenko’s work, these figures acquire an ironic character. But, let’s face it, to those of us who are far from that culture, who did not experience the era of socialist realism, these works communicate little. Since the outbreak of the war Lesia Khomenko has continued to paint massive, gigantic figures. Only those images have now become repeatedly, obsessively, the portrait of her husband at war, in military uniform, with face and symbols erased, as images from the front cannot be conveyed. The artist posted her husband’s monumental figures on social media almost daily, and in them one could recognize a feeling, an intensity, that one could not glimpse in previous works. The artistic practice ended up coinciding with her personal story, found a deep, real reason, which reflected, after all, that of so many Ukrainian wives who emigrated abroad while their husbands were forced to go off to fight.

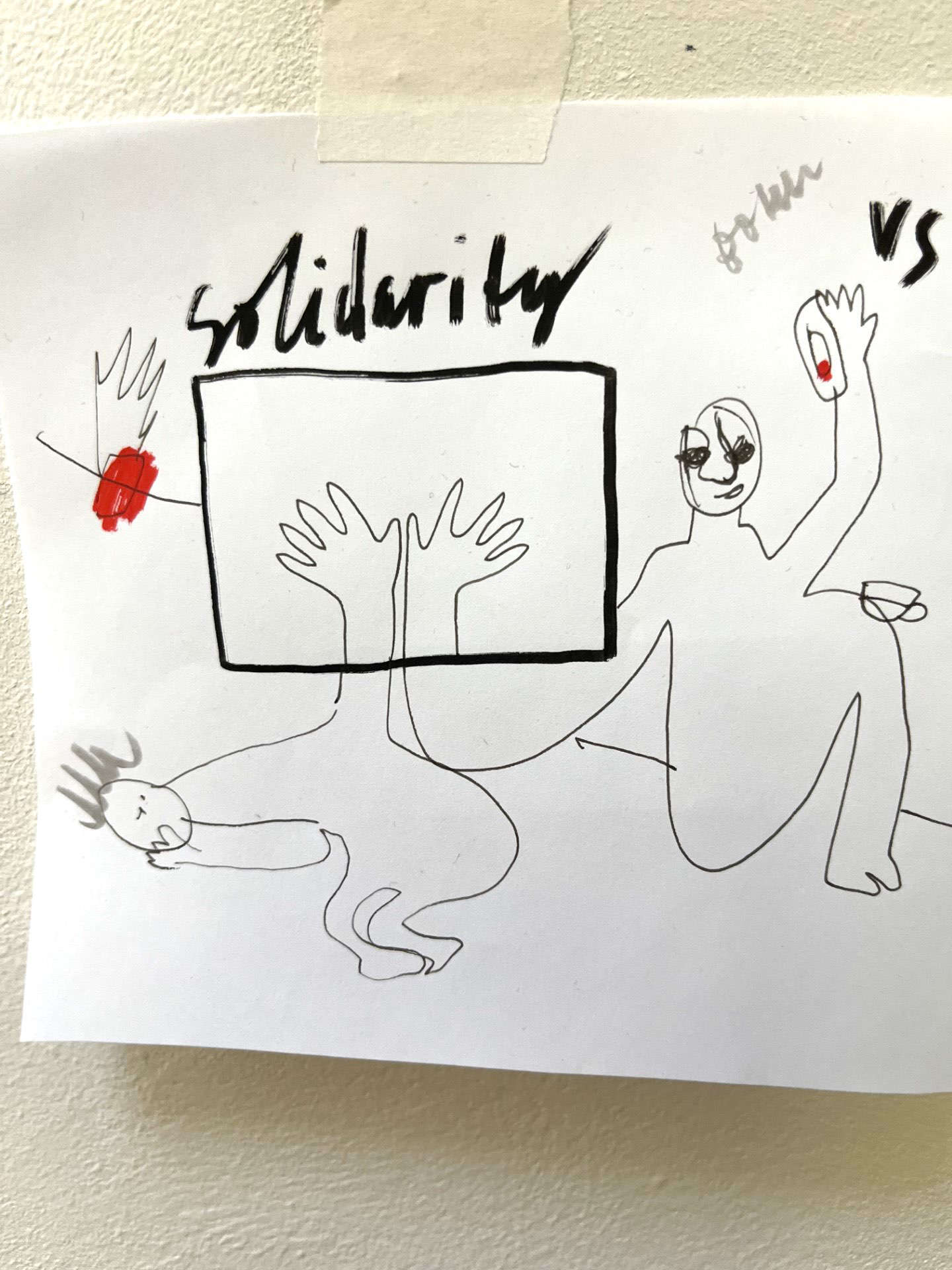

The same is true, in a different way, for other artists. Alevtina Kakhidze is an ironic and volcanic artist who makes performances, installations and drawings. She lives in the countryside on the outskirts of Kiev, and at the beginning of the war she found herself almost surrounded by Russian tanks, the ones that carried out the Bucha and Irpin massacres. She heard the artillery shots, the bombs all around her, and it was risky to move away from the village. She too posted drawings every day, ironic images that make the drama shine through, with gunmen and explosions, troop movements, hints of the political situation, of foreign support that, however, leaves only Ukrainians to fight and die. Even invited to leave, to go abroad on an art residency, she decided to stay. It is her way of contributing to the war, with her presence and daily artistic communication on social media. Then there is Nikita Kadan, the charismatic leader of the REP group and theoretical mind of this whole generation of Ukrainian artists now coming of age. He is a very conceptual artist, sometimes I would say almost conceptual, with his references to details of Ukrainian and Russian history. When the war came he decided to lock himself in the basement of a gallery, a kind of bunker, and made a series of charcoal drawings: they are shadows on the earth: the footprints, or perhaps the holes, of dead soldiers. He leaves behind for a while the learned lucubrations about monuments and history, and confronts himself, poetically, with reality. So does Zhanna Kadyrova, perhaps the most famous artist of this generation, who has participated in international biennials and exhibitions and who in Italy works with Galleria Continua. During the first months of the war she retreated to the countryside, to a house without water, where her cell phone had no service. There nearby, by the river, he discovers round stones, which look very much like Ukrainian bread loaves. He slices them and places them on set tables. Palianytsia, is the name of the type of bread and also the title of the work. It hints at food sharing and community. So much so that he produces editions of these works that he sells, the proceeds of which go to artists called to war and those in need. But there is an additional meaning in Palianytsia. Only those who are Ukrainian can pronounce the word correctly. Russians who try are immediately recognized. It is a revealing word; it marks a sharp division between two peoples that may not have been there before but is now forever defined.

Here, what happened with the war. Art and artists, who usually do not have a clearly recognized function in contemporary society, found a social and civil reason again: that of defining Ukrainian identity. In the first moments after the invasion, anything could have happened. Putin’s aim - it is well known - was to oust Zelensky and bring in a puppet government, relying on the support of many. But the heinous aggression got the opposite reaction, that even Russian-speaking Ukrainians thought the attack reckless and saw Russia as an enemy. At this juncture, in this dramatic situation, politically and culturally as well as on the ground, artists had the important function of helping to define their nation. It sounds strange, but it is precisely in response to trauma that art rediscovers its value to society. Which then, if we think about it, has always been to build a milieu of common cultural knowledge.

Drawings

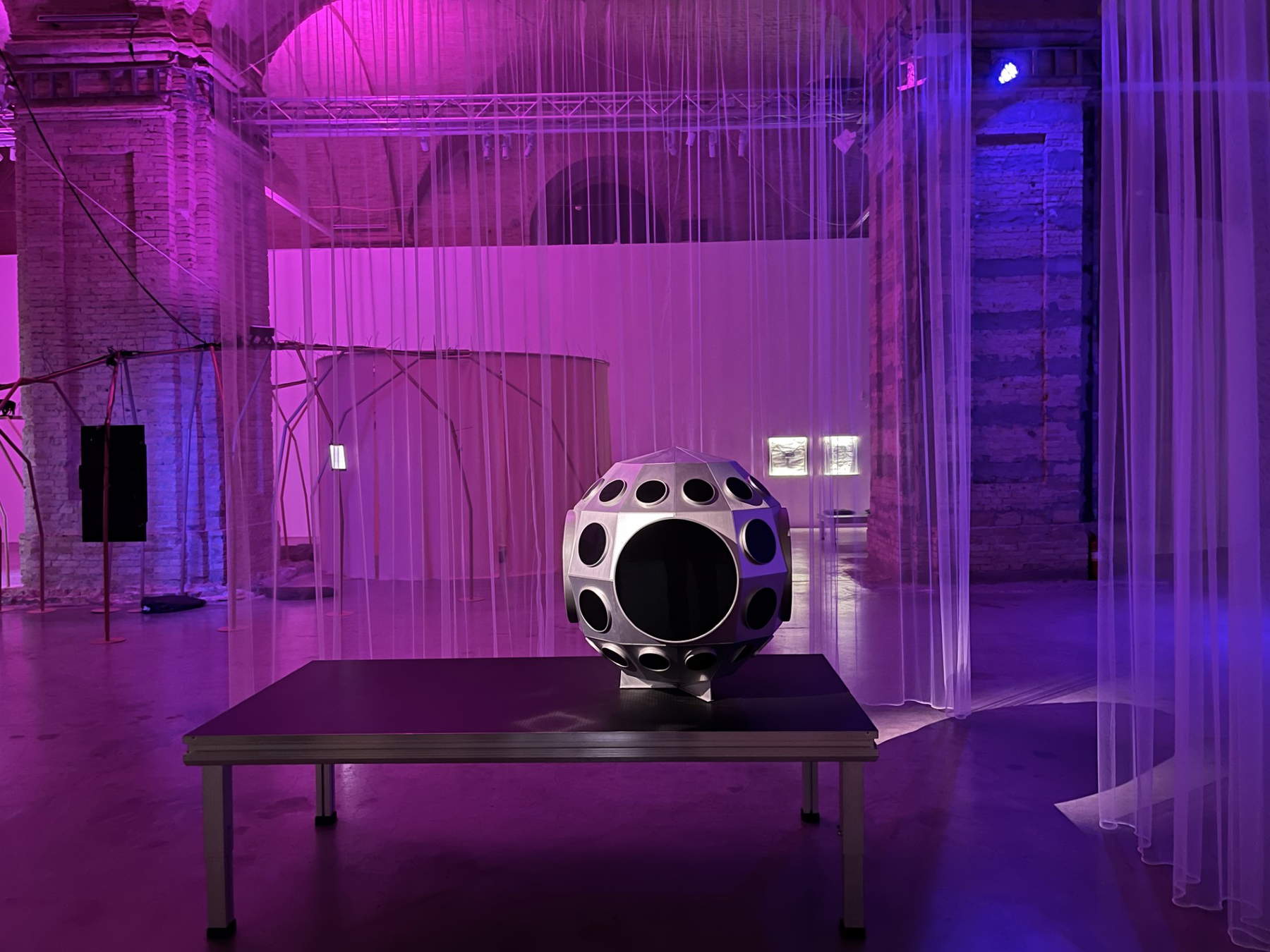

DrawingsThe trip to Ukraine was filled with many visits and meetings. Temporarily closed Pinchuk Foundation, however, there is Mystetskyi Arsenal, which at 45,000 square meters is the largest art space in Europe. During Covid it had also served artists and groups to create new work, such as that of Opera Aperta, of music composers experimenting with reinventing a contemporary opera. Now at the Arsenal there is an exhibition running until the end of March, Coexisting with Darkness, which refers to the period when Russian bombing was directed at energy infrastructure and most cities had to live with long periods of darkness and cold. Mind warping, as a museum director, when I visit an exhibition space I am usually interested in understanding how many visitors attend it on a daily basis. Here, there was no need to ask, because in the short time of my stay I could see for myself the dozens of people who came by, including many mothers with children.

We also meet Olga Balashova, former deputy director of the National Museum, who now works for an NGO that intends to establish a National Museum of Contemporary Art. A new concept, a diffuse museum that should be based in many cities, without transferring the collections of local artists to a single center, but leaving them right where they originated. During the war he started an archive, Wartime Art Archive, which collects daily the most interesting images produced as of February 24, 2022. From this archive, a few months ago, an exhibition had been held at the former Lenin Museum, in which about 100 artists participated. Closed a few weeks ago, those who saw it testify to a generalized character: the lack of color, the gray dominant of the works on display.

Ilya Zabolotny I met when he was a very young and very capable production manager of the Ukrainian-Polish pavilion for which I was commissioner at the first Kiev Biennale in 2012. Now, with the onset of war, he founded the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund to support artists in need. Once the first emergency period has passed, the fund aims to develop as an ongoing support tool, like a Dutch Mondrian Fund or our Italian Council.

With the war there was also an international explosion of interest in Ukrainian art. Artists were invited for conferences, exhibitions and residencies around the world. This contributed in no small part to the adrenaline rush that then went into the works. “October 7 marked the end of this momentum,” says Nikita Kadan. The start of the war in the Middle East diverted attention away from Ukraine, which has since begun to drop off the front page. And if this decline in interest can be observed in political affairs (think of the refusal of American conservatives to approve new aid), it also applies to artists. Nikita Kadan testifies to a dramatic collapse in international contacts, made up of exchanges of e mails or messages, after the Hamas attack on Israel.

But going back to the reasons for this trip, it can be confirmed that such a traumatic event as the war strongly reinforced, at least in the first phase, the artistic situation. Although, it must be admitted, even such a disruptive event over a period of time is reabsorbed into routine. But in this time frame art has acquired a more prominent place in Ukrainian society. This can be seen in the government’s continued economic commitment to culture, despite wartime necessities.

It is a lesson for our artists as well, in a world like the West that has so far been too confident in a peace taken for granted and good living conditions obtained forever. Do we need a war to develop a more sincere and profound art? Of course we don’t. But artists and institutions could try to confront the more arduous problems, the open wounds in our society, which are not always necessarily physical in nature, such as a conflict, but which are certainly not lacking in us as well at this overall conflicted and traumatic time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.