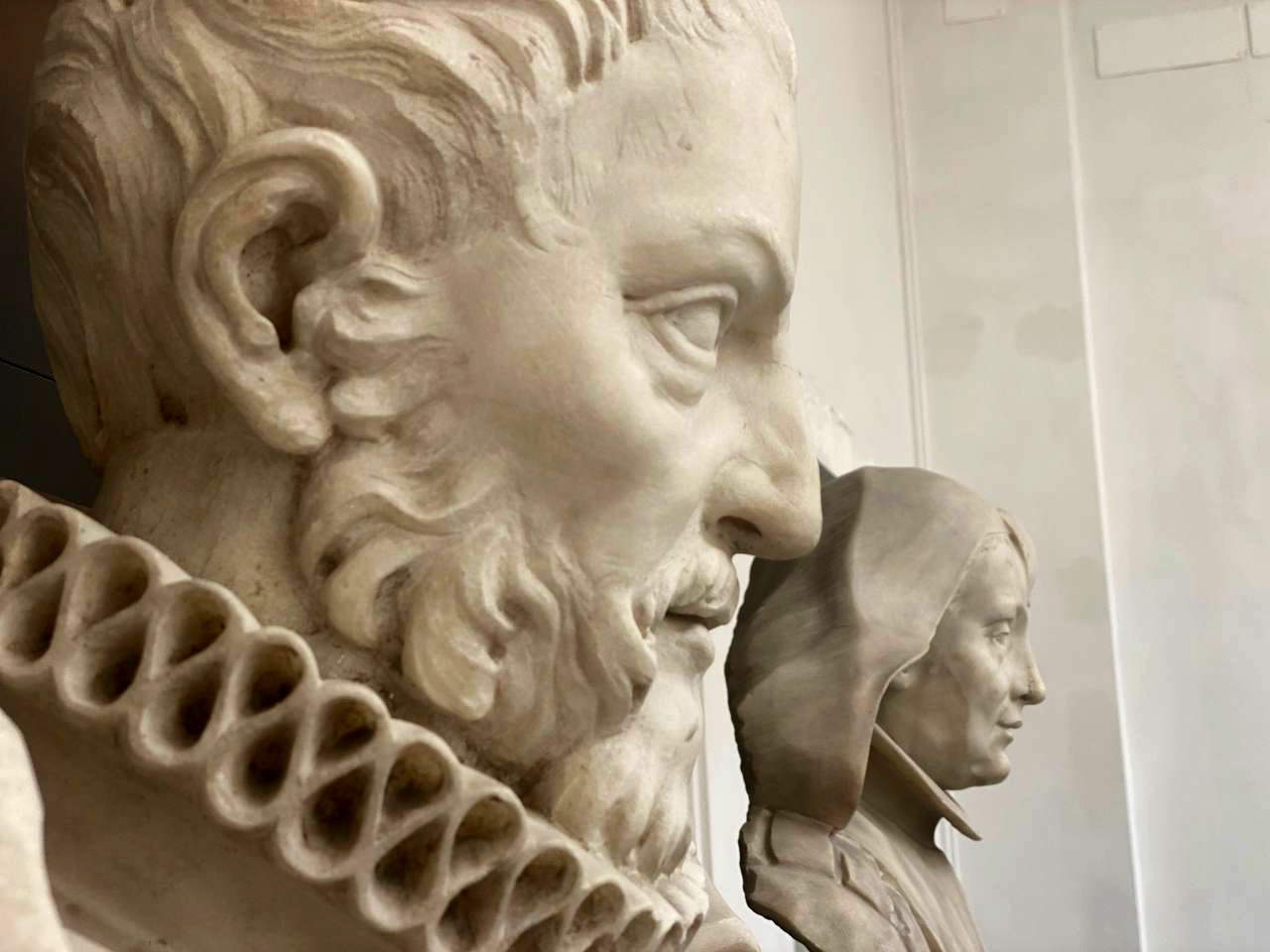

A major discovery for seventeenth-century Geno ese art and an exceptional donation for the City of Genoa: in fact, the municipal heritage has been enriched by an important pair of marble busts made by sculptor Daniele Solaro (Genoa, 1649 - 1709), depicting the spouses Tommaso Gentile and Ginetta Pinelli, which were found thanks to the work of the very young art historian Gabriele Langosco, born in 1994. The two busts come from the basilica of the Santissima Annunziata del Vastato, and the donation, made possible thanks to the generosity of the Lavarello family, owner of the work, will make it possible to reconstruct, after more than 70 years, one of the basilica’s most precious rooms.

The two busts, in fact, were made for the Gentile family chapel in the basilica, but were lost during the bombings that hit Genoa during World War II. “It was almost certain,” said Piero Boccardo, superintendent of the Civic Art Collections of the City of Genoa, “that the works had been destroyed as a result of the bombing, because in addition to the immediate destruction by the bombs, there had also been dispersions related to the general situation of the city under the effect of the bombs. The credit for the find belongs to Gabriele Langosco, and as the representative of the municipality for what concerns its artistic heritage, since the Church of the Annunziata is a municipally owned church, I affirm that this is an enrichment for the church’s heritage.”

|

| The bust of Tommaso Gentile and that of Ginetta Pinelli, works by Daniele Solaro |

Tommaso Gentile, a member of an important Genoese family about whose life, at the present state of studies, we know nothing, had arranged in his will of 1625 (the date of his passing is not known, however) for the erection of a chapel in the church of Santissima Annunziata del Vastato. His wife, Ginetta Pinelli, also a personage virtually unknown to scholars, outlived her husband by some 20 years, and when writing her will she increased the bequest earmarked for the decoration of the chapel desired by her husband.

“The decoration of the aristocratic sacellums in the church of the Vastato,” Gabriele Langosco explains to Finestre Sull’Arte, “is a complex affair and at the same time (compared to other contexts) richly documented. If the Franciscan church had to take on a new look in the first decades of the seventeenth century, it was only from the 1770s onward that there was an acceleration of investment by the aristocrats in giving new shape to the side chapels. The attitude of the Gentile family aligned with that of other lineages, and so, in the face of the 1625 bequest, work on the chapel did not begin until 1678.”

The chapel building site was initiated by the couple’s grandchildren, and the work was entrusted to the workshop of sculptor Carlo Solaro, Daniele’s father and an artist probably originally from Carona in the Brembana Valley. Carlo Solaro was part of that very large community of marble workers active in Genoa but originally from the Lombard lakes area: it was a community that, since the Middle Ages, had all but monopolized stone working in the city. Carlo Solaro led a workshop that was capable of running several construction sites simultaneously, and he managed to secure several contracts for the marble decoration of chapels at the Vastato, including those of the Invrea and Gentile families.

“The design (not preserved) that Carlo had to follow in the realization of the Gentile chapel,” Langosco further explains, "was probably the work of Domenico Piola, author of the altarpiece of the sacellum, depicting theAnnunciation and signed 1679." Piola’sAnnunciation, moreover, was also recently restored with a view to its display in the exhibition A Superb Baroque: Art in Genoa, 1600-1750, the major exhibition on seventeenth-century Genoese art that was scheduled for fall-winter 2021 at the National Gallery in Washington but was canceled due to Covid-related problems.

|

| The Santissima Annunziata del Vastato. Photograph by Joachim Kohler |

|

| Domenico Piola’s Annunciation. Photograph by Francesco Bini |

“Among the elements that Carlo undertook to provide in 1678 for the chapel,” Langosco continues, “are also the two marble busts of the chapel’s founders. Already for some years Charles, of whom we know of no statuary works, entrusted almost every figurative element in his sites to his son Daniele. Daniele Solaro is an interesting figure in the Genoese Baroque, about whose training there are still many doubts. The artist was able to develop a language that, although still anchored in the figurative stylistic features adopted by the Lombard-Genovese sculptors of the early seventeenth century, consciously looks to Pugettian statuary and Baroque portraiture. I do not think there is any doubt in recognizing the two busts, although marked by a slight qualitative disparity, as the work of his chisel. Moreover, Charles died in the eighties, and when Daniele subcontracted out part of the work on the chapel, which lasted until at least 1682, he did not entrust other artists with the execution of the statuary (perhaps suggesting that he dealt with it directly).”

Tommaso’s bust is somewhat rougher in workmanship and stereotypical in physiognomy, while Ginetta’s is finer in features and more accurately conducted. “Since they are both posthumous portraits,” says the scholar, “it occurs to me that the patrons provided the artists with a good portrait of the woman (moreover depicted with a widow’s veil), and a few scribbles representing the man, who had been dead for some fifty years by then.” The busts were placed in two marble shells in the chapel, and in 1922 they were photographed to illustrate a pioneering article on Daniele Solaro signed by Mario Labò, and published in the magazine Rassegna d’Arte Antica e Moderna. It was an article substantiated by a good deal of archival discovery. In 1942, as mentioned above, the chapel was severely damaged by a bombing raid: thanks to a photo taken in the aftermath of the air raid, it is possible to establish that the busts survived the collapse.

However, at the end of the war they disappeared, and we do not know what happened to them, partly because the documents are silent about their fate. Probably, given the loss of the roof of the chapel (which was decorated with frescoes by Giovanni Andrea Carlone), the works in the sacellum had been placed in some warehouse (the statue of Ginetta, moreover, still bears an inventory-like number written on its chest). From there the portraits may have dispersed or (according to the young art historian, such a scenario cannot be ruled out) were sold to finance the reconstruction of the chapel. There is another hypothesis: they may have been stolen, ending up a few years later in the antiques market. Then, at an undetermined date, probably between the 1950s and the 1960s, they entered a private collection. And from that date to the present their story continues precisely in the sphere of private collecting.

|

| Detail of the two busts |

“A few months ago, in view of an inheritance division,” Gabriele Langosco tells us, “the current owners had commissioned art consultant Maurizio Romanengo to draw up an appraisal of the collection. The sensitivity of Dr. Romanengo, a talented art historian and dear friend (who had been able to recognize the artistic value of the works), led to my involvement in the matter as a scholar of Genoese sculpture.”

“The recognition,” the scholar admits, "was nothing more than a stroke of luck. I had previously had the honor of writing Daniele Solaro’s entry for the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, and I had the photographs published by Labò in 1922 well in my mind, which led me to easily establish the origin of the two pieces. Once I notified the owners of the busts’ provenance, they immediately mobilized for their return." In short, luck, we feel to say, counts up to a certain point: it is thanks to Gabriele Langosco’s knowledge if the two portraits spotted in a private collection could be identified as the lost portraits of Tommaso Gentile and Ginetta Pinelli. A fortuitous chance, however, that might not have led to this result without Langosco’s study and skills.

Following the discovery, the two busts were taken over by the City of Genoa, which owns the basilica of Santissima Annunziata del Vastato. The forfeiture of the goods was taken care of by the aforementioned Piero Boccardo, superintendent of the Civic Collections, while Lieutenant Carlo Ferro, of the Carabinieri’s Cultural Heritage Protection Unit, launched an investigation to determine whether a crime had been committed. “We intervened,” Ferro said, “after the assets had been traced. We reconstructed the passages of these goods to make sure that they were indeed the ones that adorned the chapel. We checked for recent criminal liability, which did not turn out to be the case, and we checked the legal validity of the donation.” Upon completion of the investigation, the busts were (and will be) temporarily displayed at the Palazzo Bianco, pending their relocation to the chapel.

For the city, therefore, this is avery important acquisition that has also come about thanks to the collaboration between the City Council, the Carabinieri’s Cultural Heritage Protection Unit and the Genoa Public Prosecutor’s Office, and to the foresight of the Lavarello family, which, having learned the history of the two busts, embarked on a path that ended with the return of the works to the City of Genoa. In the Gentile Chapel they will find the altarpiece by Domenico Piola, which will return shortly after major conservation restoration and after it will be displayed at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome for the Italian leg of the Genoese Baroque exhibition whose prologue was scheduled to be held in Washington. “We are reappropriating an asset, these marvelous marble busts from the 17th century that are being returned and donated to the city,” said Barbara Grosso, Councillor for Culture of the City of Genoa. “A restitution, but also a donation, really a nice gesture. These busts had been forgotten and will be relocated to the place from which they came. In the coming months we will work to relocate them inside the Church of the Annunziata.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.