Between art and science, the Botanical Museum of the University of Pisa.

Heirs to immense cultural and scientific heritages, university museums are called upon in our contemporary times to face the age-old problem of variegated collections, made up of objects that are not easy to read, pertaining to sectorial fields of employment and research, and no longer always responding to the primary function for which they were collected, namely study. Not surprisingly, science museums, not only at universities, are at the center of numerous museological debates, with the National Association of Science Museums (ANMS) among the protagonists in Italy. Although we are still far from formulating easy and unambiguous solutions for the enhancement of these museums, there should be no doubts about the importance of facing the challenge to ensure, on the one hand, the continuity of their preservation and, on the other, a fruition that is no longer merely directed to scholars of the subject, but to a general and composite public, which in addition to the objective of erudition also has that of entertainment and leisure. “Born from the separation of scientific and artistic collections, they preserve evidence and links between them,” says Fausto Barbagli, president of ANMS. These museums “all have a scientific importance and a cultural and social relevance that dialogue with the territory”: for this reason, their enhancement is not a secondary objective, even if the chronic lack of funds also complicates the picture.

The Botanical Museum of the University of Pisa undoubtedly succeeds in combining scientific rigor and pleasantness in the visit, even for a lay audience. Its history is inextricably intertwined with that of theBotanical Garden of the University of Pisa, with which it still forms a single fascinating complex. The museum finds its premises in two episodes: the first coincides with the founding act of the Garden in 1543, when Luca Ghini, a physician and botanist from Imola, was called by Grand Duke Cosimo I to hold the chair of the University of Pisa. The scholar set as a condition for his employment the need for the government to allow the organization of a “Giardino dei Semplici,” where plants with medicinal properties could be cultivated. Ghini simultaneously introduced two fundamental tools into the Pisan study, which would later become the skeleton of the later museum: thehortus siccus, or herbarium with dried plants, and thehortus pictus, a painted iconographic collection of plants and flowers. The Botanical Museum is also heir to the gallery commissioned in 1591 by Ferdinando I de’ Medici, organized as a Wunderkammer between naturalia and artificialia.

Today the museum is located in the 18th-century spaces that were originally those of the foundry, a place deputed to the preparation of medicinal composites. It is accessed through the door set into the sumptuous Rococo facade, which is entirely covered with an encrustation of varied materials ranging from pink granite and other rocks to casts of shells and madrepores, forming bizarre decorations and the coat of arms of the Grand Ducal Lorraine family. The museum, as conservator Roberta Vangelisti says, houses materials that are difficult to access, since the main collection is theherbarium, which is of interest primarily to scholars and is almost entirely kept in another location, where it can be consulted by appointment. The remaining ancillary collections are related to the teaching of botany, particularly from the 19th century, when this discipline separated from medicine, of which it was once a part. The museum institute has recently been rearranged to make it less complex to consult the material on display and will soon undergo further work.

Welcoming the visitor is a portrait of the father of the garden and the museum, that Luca Ghini we have previously mentioned, whose famous herbarium has unfortunately been lost, as have those from later centuries, probably related to the Grand Ducal family’s desire to move them to Florence.

Among the oldest artifacts on display, also in the entrance hall, is the monumental walnut wood door, which originally gave access to the garden and gallery from Via Santa Maria. The 16th-century door is embellished with detailed bas-relief carved depictions of plants, including the Fritillaria imperialis, a bulbous plant of oriental origin that has become the logo of the Botanical Garden of Pisa.

This is followed by a small but evocative reconstruction of the 16th-century chamber of wonders, where taxidermied animals, fossils, minerals and other curiosities are reminiscent of the historic Pisan Wunderkammer , celebrated at the time for its size and for the exceptional nature of its exhibits, such as the human skull from which a coral twig sprouts. While numerous items were dispersed over the centuries, many, including the famous skull, went on to form the original nucleus of the University of Pisa’s Museum of Natural History in Calci, where they too are today displayed in a much larger reproduction of the wunderkammer.

The next room, on the other hand, displays a large group of portraits of mediocre quality but of great historical value, also from the gallery, and shows personalities associated with the teaching of botany p the garden, including various prefects who have succeeded one another throughout history. These include the portrait of Andrea Cesalpino, Ghini’s successor at the helm of the garden from 1555, and the Flemish Giuseppe Casabona, who not only supervised the re-founding of the garden from its previous position to the one it currently occupies, but in the last decade of the 16th century undertook, at the behest of Ferdinand I, a trip to Crete with the intention of collecting samples of the local flora.

On that occasion he met the German soldier Georg Dyckman, whose remarkable painting skills enabled him to enrich his trip with 36 tempera plates depicting plants of great scientific importance, now preserved in the University Library of Pisa but partially reproduced here digitally. These plates show one of the many cases that highlight the happy union between painting and botany, a relationship that has not been interrupted even in our modern times, so much so that new discoveries in the field are not infrequently accompanied not only by dried specimens, but also by painted or drawn illustrations, which continue to have considerable advantages over photography in rendering plants. Inserting itself into this groove, courses in botanical painting are held at the museum, taught by artist Silvana Rava, internationally famous for her works with a scientific bent, which are not infrequently displayed at the Pisan institution in temporary exhibitions.

Continuing the visit, one encounters another figure of great importance to the Pisan Athenaeum: the physician and naturalist Gaetano Savi, who at the turn of the 18th century and the following century made considerable efforts for the study of botany, enfranchising it from other natural sciences and medicine. He is also credited with the implementation of the Pisan herbarium.

Certainly the most fascinating collection, even for laymen of the subject, is the rich collection of 19th-century models in plaster, wax and other materials, used for teaching purposes. They are reproductions of plants, fungi and fruits, sometimes on a much larger scale than life, made with great virtuosity and achieving a high degree of naturalism, due in large part to the skillful hand of waxmaker Luigi Calamai, also the author of anatomical waxes for the University of Florence, and his school.

The model representing the fertilization of the gourd was presented at the first meeting of Italian scientists in 1839, held at the garden, and was highly appreciated by Grand Duke Leopold II, who wanted to purchase it. The wax model illustrates the discoveries of engineer Giovan Battista Amici, conducted through microscopic observation, regarding the reproduction process in angiosperms. Other anatomical models of plants show different phenomena, such as the attack of pests or the structure of a leaf. These valuable reproductions have recently been restored, since in the not too distant past, having lost their didactic function, their preservation had been rather neglected.

Also vast and of great interest is the section of mushroom models in polymateric structure. Among other curiosities, one also discovers the seed of coco de mer, a palm known to have the largest seeds in the world, weighing up to 20 kilograms, or samples of fiber plants purchased at the Colonial Exhibition in Marseille in 1906.

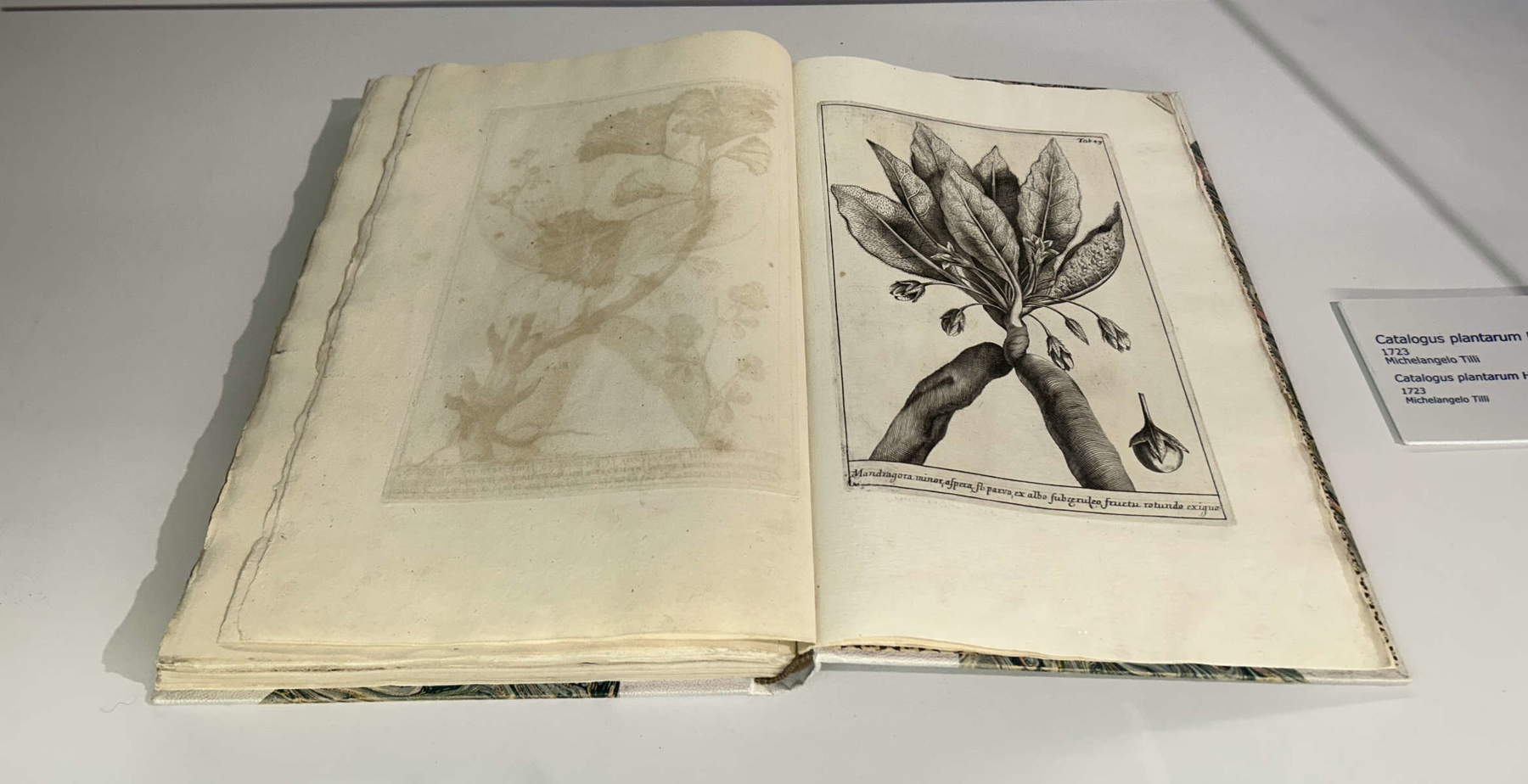

The end point of the visit is the room that houses, in rotation, some of the 96 original and restored plates depicting plants and shrubs painted in ink or watercolor. These works, used in teaching, particularly by Professor Pietro Savi, were employed in classroom lectures until the first half of the twentieth century. The plates are also accompanied by a copy of the catalog compiled by Savi himself, which contains captions and explanations. A selection of paleobotanical artifacts with fossil trunks, and specimens from the herbaria, which can also be consulted through a digital screen, complete the itinerary.

By exhibiting a route that interweaves the history of the Ateneo Pisano with that of the garden and the study of botany, studded with great personalities and continuous innovations, the Botanical Museum, while certainly not having abandoned its scientific and scholarly intentions, also manages to offer itself as an interesting experience for visitors uninitiated in the subject, thanks in part to the numerous initiatives organized here, from lectures to exhibitions, from painting courses to photography contests and more. Therefore, the Botanical Museum represents an added value to a visit to the already fascinating Botanical Garden.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.