Art history in Renzi's good school? Hopes hanging by a thin thread. And reform slipped

Exactly one year ago, day more, day less (it was June 19), Education Minister Stefania Giannini triumphantly announced the return of art history to school: “we will introduce the study of art history, in all levels of high schools, starting from the two-year period, of course with a dosage of hours proportionate to the curriculum, and then of weekly hours to grow, for the three-year period of both the humanities and in the tourism institute.” These were the beginnings of the bill known as the"good school": a reform on which Premier Matteo Renzi is playing most of his cards.

What happens next? Sessions and consultations begin, and on March 27, 2015, Act 2994: “Reform of the national education and training system and delegation for the reorganization of existing legislative provisions” is presented in the Chamber of Deputies. It is the Renzian good school bill. It touches immediately on the sad fact that art history lacks the slightest trace, despite Stefania Giannini’s bombastic announcements, followed by those of so many politicians who for months have hailed the “good school” as the epoch-making reform that has been needed for years. And that it would reintroduce art history in school, of course. In January, for example, Cultural Heritage Minister Dario Franceschini claimed that “studying Giotto is like studying Dante,” thus making people believe that there could be no school without art history. But, evidently, for many of his colleagues the word “Giotto” only identifies a well-known brand of markers (and perhaps not even this one), and it is a fact that in the text of March 27 the locution “history of art” did not appear, if only once. The latter is introduced only in the text approved by the House and transmitted to the Senate(Act 1934), but a strong sense of vagueness still dominates. No indication of how and where to reintroduce it, by what time and means, no mention of teaching. Only a generic indication (article 2, paragraph 3) of “educational objectives identified as a priority,” which educational institutions should achieve: among these objectives, the “strengthening of skills in musical practice and culture, art and art history, cinema, techniques and media for the production and dissemination of images and sounds, including through the involvement of museums and other public and private institutions operating in these areas,” and “art literacy.” And enough.

|

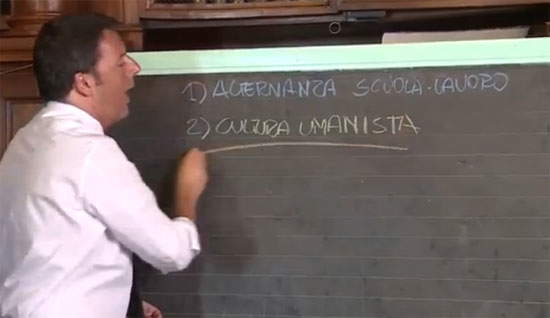

| Renzi presents the good school on May 13. With conspicuous grammatical error |

The text is still under consideration by the Senate Culture and Education Committee, but it was just a few minutes ago that Matteo Renzi himself proposed a postponement of the work. Punctual as a Swiss-made watch, just two days after the closing of the elections chapter, from which the PD came out with broken bones losing strongholds such as Venice and Arezzo, the premier spoke on one of the central nodes of the reform: the alleged, hypothetical, who knows how probable and perhaps unhoped-for as well as difficult to achieve stabilization of one hundred thousand precarious workers. And he said that these hirings are impossible by September. The blame? Not on the fact that it is unclear how the precarious workers will be hired and stabilized. Blame too many amendments to the bill, according to Renzi. With the result that a reform announced a year ago and worked on for months will probably slip to next fall: and with it our hopes of seeing art history in school again. Carve out the reform’s points on precarious workers by approving their stabilization by decree, as suggested by Corradino Mineo and others, and then let the work proceed smoothly? Too difficult! No way, and in fact everything is blocked. The 5-Star Movement speaks of an"ignoble plan," concocted by Renzi to get the votes of precarious teachers in the local elections (only to then renege on his promises just two days after the outcome of the elections). The council president, for his part, postpones everything until July: a national conference will be used to take stock of the situation.

And the art history talk? For now, it remains hanging on a small number of amendments presented by some members of Sel and the mixed group (including Alessia Petraglia, who summarized these and other amendments on her website), who intend to supplement the text of the bill with precise indications on how to reintroduce art at school (schedules, types of institutes) and on what should be the budgeted expenses to make the operation possible.

In short, art history hanging by a thread tied to what seems to be yet another Italian-style political mess: bombastic promises, made moreover on the skin of those who would like to achieve their dream of teaching indefinitely, resounding announcements then disregarded with the first draft of the law, and expectations of many who must rely only on faint hopes. Perhaps it is too early to say that art history will not return to school (just as it is too early to say that the hundred thousand will be disappointed), but today we can certainly say that the timeframe will be considerably longer. And it is by no means certain that it will be achieved in the end.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.