All about Caravaggio's Ecce Homo. Here's what was discussed at the Genoa conference

One of the most complex works of Caravaggio ’s (Michelangelo Merisi; Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) production, rediscovered only in the twentieth century, capable of animating passionate debates between those who assign its authorship to the great Lombard master and those who are skeptical and do not go so far as to attribute it to his hand: this isEcce Homo preserved in Genoa, at Palazzo Bianco, and until June 24 the protagonist of the exhibition Caravaggio and the Genoese. Clients, Collectors, Painters, set up at Palazzo della Meridiana in the Ligurian capital(at this link you can read our review, where readers will also find a brief summary of the main positions on the attribution, and the salient stages of its rediscovery). On Wednesday, at Palazzo della Meridiana itself, theEcce Homo was the protagonist of a conference, entitled Around Caravaggio’ sEcceHomo from Palazzo Bianco, curated by Anna Orlando (who is also curator of the exhibition), organized to take stock of the progress of studies around the important painting.

|

| Images from the exhibition Caravaggio and the Genoese |

|

| Caravaggio, Ecce Homo (c. 1605-1610; oil on canvas, 128 x 103 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

After institutional greetings by Davide Viziano, president of the Association of Friends of Palazzo della Meridiana, Barbara Grosso, councillor for culture of the City of Genoa, and Ilaria Cavo, councillor for culture of the Region of Liguria, the floor went to Cristina Bonavera, restorer, author of the last intervention onEcce Homo, dating back to 2003 and almost forgotten until this year. “When we began our restoration work,” Bonavera reported, “the painting was in a poor state of preservation: it had undergone two previous restorations, an eighteenth-century one, during which it had been cut down along the edges in the most ruined parts, and one in 1954 carried out by Pico Cellini and conducted under the direction of Roberto Longhi and Caterina Marcenaro. Longhi and Marcenaro decided to restore the painting to the original dimensions of the copy kept at the Regional Museum of Messina, so if before the work measured 118 x 96 cm, it was later enlarged along the edges to its current dimensions, which are 128 x 103 cm. Before our restoration work, the painting had tears due to damage suffered both in the previous restoration and in the bombing that hit the Royal Naval School in Palazzo Giustiniani Cambiaso, where the painting was kept during World War II.”

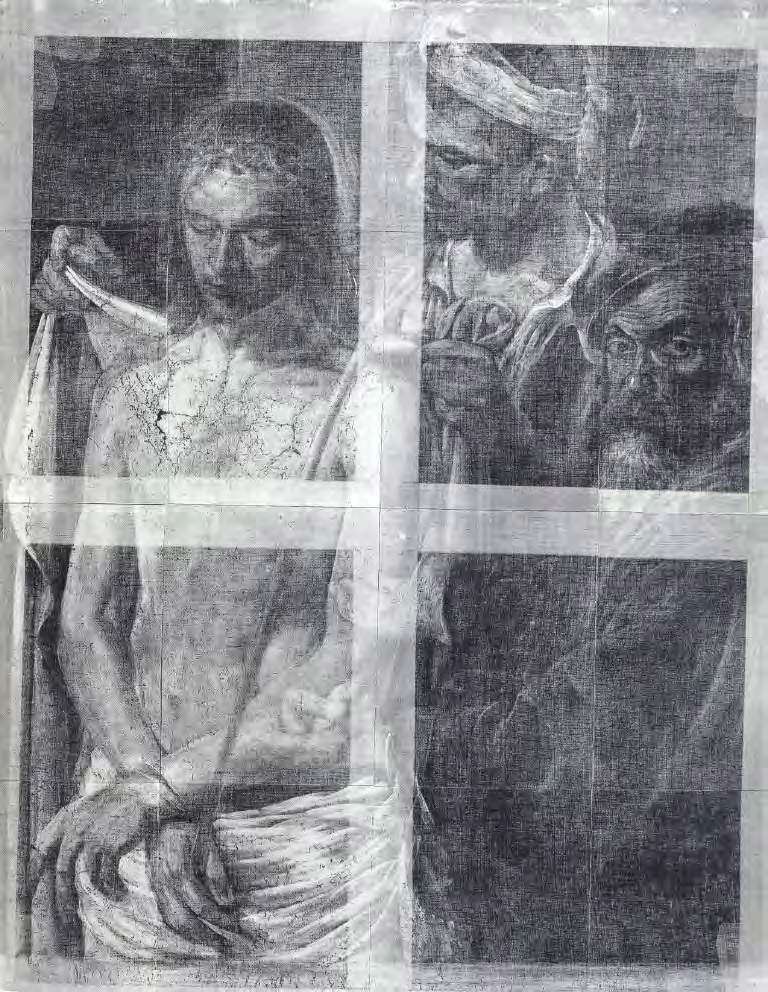

Before starting the restoration, Bonavera recalled, “diagnostic investigations were carried out to better understand both the materials and layers of the work and its state of preservation (thus to better address the restoration work), and also for a deeper understanding of the artist’s technique. These analyses reveal to us the elements of Caravaggio’s painting technique: color sketches, etchings, pentimenti, overlapping of pictorial backgrounds, and sparing preparation technique. Especially in the x-rays we can see at the shoulder and arm the reduction made by the artist himself, who spread darker brushstrokes along the arm and shoulder to cover and correct an earlier drafting of his own. What we see around Christ’s shoulder is a sketch of white color: we know that Caravaggio did not draw but drew quick sketches of color with a brush, directly on the preparation, fixing the main points of the composition. Another characteristic of Caravaggio’s paintings are the pentimenti: this technique of his, so quick and so immediate, involved afterthoughts and corrections, which can be seen in the x-ray but also with the naked eye. Other typical elements of the painter can be seen in Pilate’s headdress that towers over the dress of the manigoldo at his side. Indeed, one of Caravaggio’s characteristics was the overlapping of pictorial backgrounds: in this case, first the figure of the manigoldo was made and later the figure of Pilate. From the X-ray we also see how Christ’s loincloth was made tighter and more in contact with the side, and the falling part is covered by the mantle of the figure of Pilate. We also find incisions in the painting: in addition to laying down the pictorial backgrounds, Caravaggio fixed the preparation by incising it, either with the back of the brush or with points. Longhi says that engravings were used by Caravaggio to reposition the models after laying, because he used to paint from life and therefore needed to fix reference points to reposition the figures in the same places. Returning to the intervention, after fixing the paint film and removing the painting from the frame, disinfestation against xylophagous insects was carried out, and then the cleaning was carried out: a more superficial cleaning was opted for, which did not completely remove the repainting.”

Finally, Bonavera concluded, from 2003 to the present, the instrumentation has improved considerably: this is why the restorer hopes thatEcce Homo can be examined with the same parameters as the comparative diagnostic analysis campaign coordinated by Rossella Vodret and Claudio Falcucci, which began in 2010, continued on the occasion of the Milan exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in 2017, and was able to involve thirty-five paintings.

|

| Total X-ray of Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo (study by Mina Gregori on the occasion of the 1992 exhibition in Florence and Rome) |

|

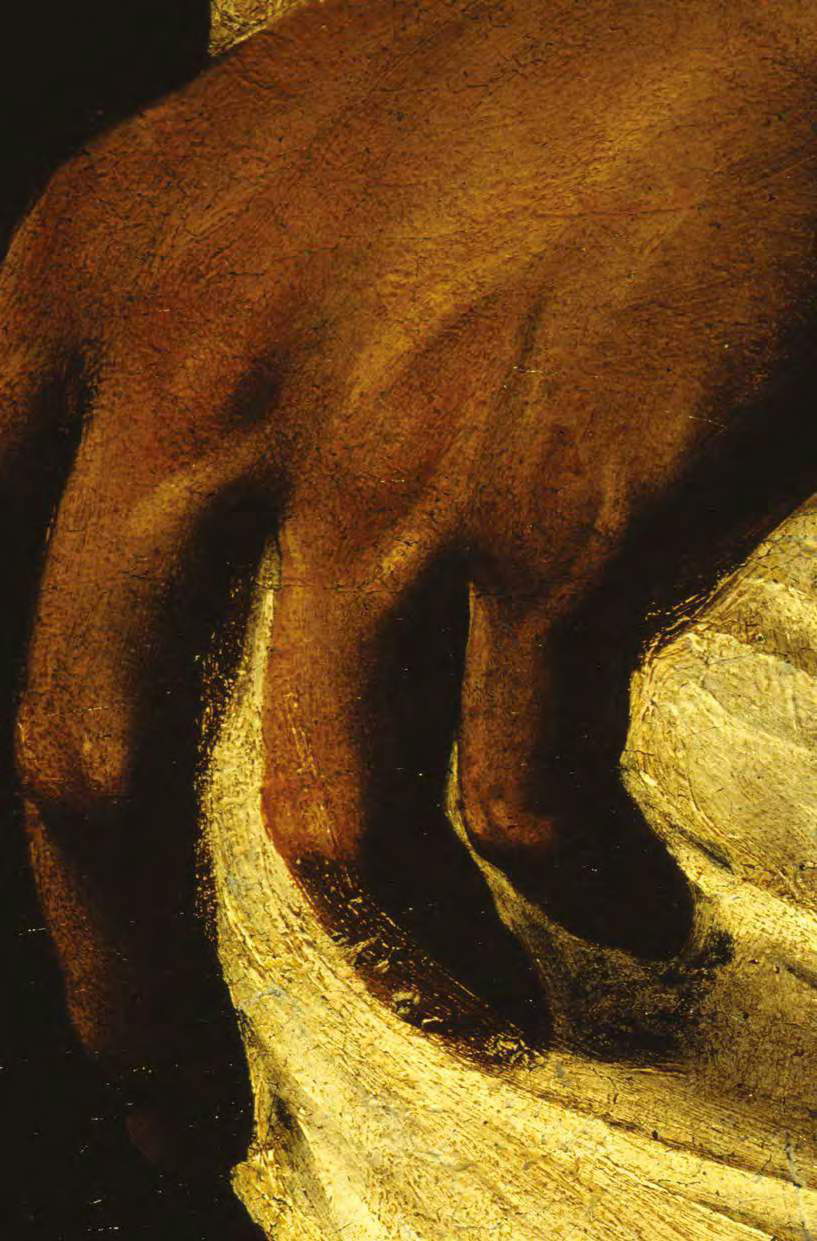

| Detail of the painting with the left hand of Christ in which the use of re-surfacing preparation, the use of brush sketches, later adjustments are visible |

|

| Detail of the painting with the hand of Christ |

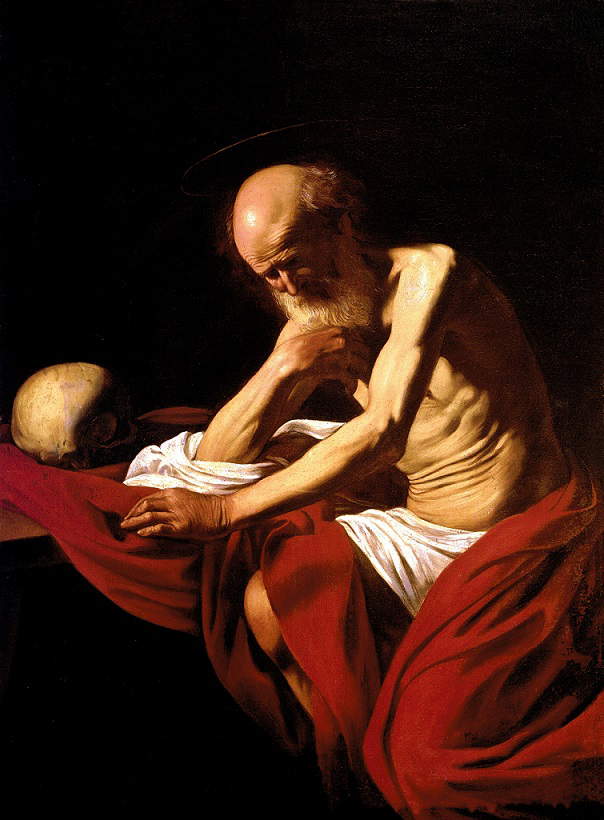

Anna Orlando ’s talk focused both onEcce Homo and on the subject of copies. "EcceHomo,“ the scholar recalled, ” came to this exhibition shortly after the Paris exhibition, and we put it in the spotlight as perhaps it has never been done before. There are obvious data (which we can certainly argue about later, data must always be interpreted): the pentimenti rule out the use of the word ’copy’ (they can be seen both with x-rays and the naked eye), the drafting is free, loose, spur-of-the-moment, it is the technique of a scornful, non-diligent painter, and this aspect, too, leads us to dismiss the hypothesis (which has been part of the critical story of the painting) that it is a copy. The superimpositions are equally evident: one can see very well with the naked eye the construction of the figure of Pilate, the least convincing, the most anomalous, the least Caravaggesque, but the whole figure is built on top of the figure of Christ and the figure of the manigoldo. Another element (certainly unmeasurable and that cannot be put on the scales, but we art historians have a duty to acknowledge it), is the fact that the Strada Nuova painting is of much higher quality than the other known copies, including the one from a private collection in Palermo that has been the subject of a major study. These are all data that are not very measurable but that make a system, and the work of the art historian I think is precisely to put all the elements at hand into a system." This is a quality that, according to Orlando, also emerged from the radiographic investigations carried out during Cristina Bonavera’s 2003 restoration, which revealed details (such as the zigzag brushwork) that can be compared to other works by Caravaggio, for example the Saint Jerome in the Montserrat Museum.

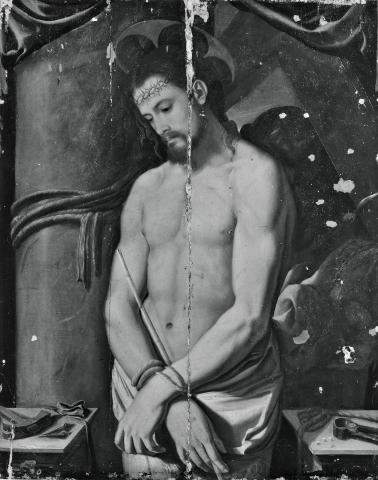

As for the theme of copies, one of the newest in the approach to Caravaggio’s art, Orlando pointed out that one of the new features of the exhibition is having theCoronation of Thorns on display from the Carthusian Monastery of Rivarolo and derived from the work (also much debated) attributed to Caravaggio and owned by the Banca Popolare di Vicenza. “This copy,” Orlando said, "is of great quality, and the provenance of the Certosa links the history of the painting to the Di Negro family: it is interesting to note that Orazio Di Negro owned one of the very first Caravaggio copies, that of theIncredulity of St. Thomas, which Vincenzo Giustiniani in his trip to Genoa sees in the house of Orazio, moreover his cousin. Until 2018, we did not know much more about Orazio Di Negro: in the course of a work in the Carte d’Arte series, we investigated the Di Negro family and an inventory from 1618 popped up where the copy of theIncredulity appears and is given to Cesare Corte. Corte is also a copyist of the Dorias, and we know this from the studies of Laura Stagno: it is clear that this circle leads us to close with conviction the theme of the attribution of the copy, made by Cesare Corte, to the Di Negros. We also see this from the colors, which belong to a painter of still sixteenth-century culture."

|

| Cesare Corte, Coronation of Thorns, copy from Caravaggio (early 17th century; oil on canvas, 203 x 166 cm; Genoa, San Bartolomeo della Certosa) |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint Jerome in Meditation (1605; oil on canvas, 118 x 81 cm; Montserrat, Museum of the Monastery of Santa Maria) |

Following this, Maria Cristina Terzaghi, after welcoming the idea of dedicating an exhibition to the theme “Caravaggio in Genoa” (which until now had never been addressed in an exhibition) and stressing the importance of the new acquisitions on the Di Negro family, led a talk on the topic of the possible provenance and dating of the work. The point of departure is Anna Orlando’s reconstruction in the light of the most recent information that sees the Di Negro and Doria families (who were in contact with Caravaggio) appearing insistently in a dense web of commissions, as well as a track already beaten until at least the 1990s, according to which theEcce Homo could be linked to the election, in 1609, of Giannettino Doria as bishop of Palermo (one fact is that all copies of theEcce Homo are found in Sicily, so it is almost certain that at some point in history the work must have been on the island), and the second hypothesis that connects the work with an Ecce Homo (of measurements compatible with those in Palazzo Bianco) that was in the collection of Juan de Lezcano, Spain’s ambassador to the Holy See. “I was very convinced,” Terzaghi said, "by the hypothesis of linking theEcce Homo to Giannettino Doria’s commissioning and, as Francesca Cappelletti had already said, disengaging it from the 1605 dating. Antonio Vannugli argued in a very important study that from Massimi’s collection the painting passed into Lezcano’s collection via the Spanish ambassador. This is not necessary: the provenance could be Sicilian and there may not be a Roman passage as assumed by Vannugli. The hypothesis of Giannettino Doria remains standing, but the hypothesis that Lezcano, from Sicily, brought the painting to Naples also remains possible."

Related to the theories on provenance then is the problem of the work’s style. “If we are to link this work to Sicily,” Terzaghi pointed out, "we need to understand with which painting from SicilyEcce Homo should be compared. If we say that this painting looks Sicilian to us, we have to find something plausible to put next to it. Certainly the Sicilian copies, as Longhi already said, lead one to think of a passage to Sicily, but if the painting is by Caravaggio we must think of it close to his certain Sicilian paintings. Certainly, as Gianni Papi noted, Caravaggio’s Sicilian paintings are in a dramatic state of preservation. The closest thing is the Nativity in Palermo, but if it is disengaged from the Sicilian moment as many say (I am not convinced) we must try to figure out whoseEcce Homo is if not Caravaggio’s, knowing that it is difficult to find hypotheses for another artist. The style remains an enigma: in my opinion the reference to Doria is convincing, and certainly the relationship with Sebastiano del Piombo’s Portrait of Andrea Doria is important (it is unequivocal), but if we tie it to Giannettino Doria we have to understand what Lanfranco Massa had in Naples [ed. note: we know from documents that Massa, Marcantonio Doria’s agent, had an unidentified Ecce Homo in Naples].“ However, Terzaghi concluded, at the moment we are working only on clues and not on evidence: that is very right and if all signs lead toward a direction we need to take it, ”keeping open, however, the possibility that some clue may escape us and appear to make us change direction."

|

| Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of Andrea Doria (1526; oil on panel, 153 x 107 cm; Genoa, Palazzo del Principe) |

|

| Caravaggio, Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis (1600?; oil on canvas, 268 x 197 cm; Palermo, formerly in the Oratory of San Lorenzo, stolen in 1969) |

The resumption of the proceedings in the afternoon began with Riccardo Lattuada’s talk, which focused mainly on Caravaggio’s technique: “Looking at the Genoa painting,” said the scholar, “I believe this method, so complicated to define, on which diagnostics is expending enormous efforts, can only lead back to a very precise cultural matrix, on which in my opinion Caravaggio depends, because he drew on it from his training to build his tools, and which is that of 16th-century Venetian painting. When the sources speak of the ’extravagant brain,’ speaking of the 6,000 scudi that he refused for the Doria frescoes, this definition not only tells us about Caravaggio’s character and life but also, in my opinion, about the perceived essentially experimental nature of his work. Caravaggio does not work with methods that are perceived as inscribed in the groove of the technical, manual and pictorial tradition of his time, but they are seen as connoted by a strong experimental component, and this is one of the most visible elements of his trajectory. These elements are not entirely detached from a historical tradition: to speak of ’brains’ is to speak of someone more than a strange person, and it is to understand that what he does each time surprises everyone, because he comes at it differently than those who preceded him or his contemporaries. Another problematic case was, for example, that of the ’most terrible brain that ever had painting,’ Tintoretto: Vasari intended to crush him, but calling him that offers the most precise definition of modernity. Caravaggio found original ways of great impact and culture shock in circles such as Rome that were not so well acquainted with the Venetian innovations that were shortly to arrive in a more massive way. However, we are not talking about a cultural descent, but a method of working: there is the idea of producing images in a much more cogent and rapidly verifiable way. All these aspects were also recombined by Caravaggio in a new and traumatizing way for the scenario in which he operated.”

Gianni Papi focused on the dating of the work: “since 2008,” said the art historian, "I have been arguing for a Sicilian chronology, that is, in 1609, of theEcceHomo in Genoa; such a solution has, after all, already been advanced in the past, even sporadically and perhaps with little conviction; it does not seem adventurous to think that the painting could have been executed for the Dorias and been sent to Genoa; it will have to be remembered that at the very time Caravaggio was staying in Palermo in 1609, Giannettino Doria was bishop of the city. And it is precisely on this contingency that Anna Orlando points (on the very occasion) to link the painting to a Sicilian execution. Moreover, similarities have been identified in Pilate’s features and clothing with a great character of the Ligurian family, namely Andrea Doria, however, such identification perhaps raises some perplexity, since the great character would be assigned, in the painting, a not particularly noble and courageous role, namely that of Pilate." After recalling that the hypothesis of a Sicilian execution ofEcce Homo had already been aired in the past (e.g., by Alfred Moir in 1967), Papi stated that this theory may also be plausible “on the level of the language” of the work. “The most probable hypothesis,” he said, "is for me a Sicilian execution (in Messina or Palermo), a pause of the painting to allow the execution of copies that would spread its lyconography in the island, and then a subsequent (certainly not late) transfer to the Ligurian capital. For example, it cannot be ruled out that lEcceHomo may be one of the four works with Storie della Passione subjects that Caravaggio was to paint for Niccolò di Giacomo in Messina."

There is, however, another plausible hypothesis, according to Papi, and it concerns the possibility that a painting by Santi di Tito, an Ecce Homo datable to the 1670s, "may have been an object of devotion for Antonio Martelli, the Florentine Knight of Malta who seems to have had increasing importance in Caravaggio’s Maltese and Messina affairs. That is, the one who, as research continues, assumes in our eyes the role of the painter’s great protector and who was Prior of the Order of Malta in Messina in the same months that Merisi arrived there. In fact, Martelli had landed there on November 1, 1608, and Caravaggio arrived there about a month later. It is really tempting to speculate that Santi’s painting was among Martelli’s possessions, a painting particularly dear to him, brought from Florence to Malta and then transferred to Messina; Merisi might therefore have seen it in the Sicilian city and, with it before his eyes, executed his Ecce Homo in Messina. This, after all, would not undermine the possibility of an already advanced Doria commission, and on the other hand would make the presence of the two copies, already mentioned, from the Messina area more logical, of which the one preserved in the city’s Regional Museum surely comes from the local church of SantAndrea Avellino."

|

| Santi di Tito, Ecce Homo (1670s; panel, 104 x 84 cm; Private collection) |

Rossella Vodret returned to the subject of diagnostic investigations, premising that these analyses “can help the art historian by revealing aspects that are not usually seen and by covering a supporting function, which is not however a substitute for the art historian, to whom the recognition of the work of art is due.” Recent investigations of Caravaggio by Vodret and Falcucci have yielded comparable results on as many as thirty-five works by Caravaggio, half of those typically attributed to him. These studies allowed for a more in-depth approach to the Lombard artist’s technique. “Caravaggio,” said Vodret, “begins to paint in the traditional way, with a clear canvas preparation and drawing on the clear preparation, exactly as all the painters of his time did. The great innovation maturing in the last years of the 16th century is when the preparations from light become dark, and this implies that the traditional drawing is no longer seen, or is seen much less. Thus begins the use of engravings, which he adopts as if they were a drawing. He will never return, at least in our experience, to the light preparations, which are no longer there after 1598-1599: there are colored preparations, red or green, but never lighter. An ingenious revolution takes place with the paintings of the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome: the painter finds himself having to create huge pictures with measurements unusual to him and so many figures, he who was used to painting small pictures with three or four figures at most. Not only that: he also had to do it quickly, the contract is dated July 1599 and the delivery had to be within the year (Caravaggio delivered the works in July 1600). So many figures, immense paintings, and he came up with an ingenious thing, partly detectable already in earlier paintings but here elevated to method: dark preparation is used for all the shaded parts. Everything seen in the background is exposed preparation, or veiled with dark where it was necessary. Given this dark preparation, Caravaggio paints only the parts in light that come forward of the background, which remains dark, thus less visible, or visible at all. Caravaggio completes the setting of the composition with sketches (initially dark brush strokes that will later become light or even red), and what he will no longer leave behind is this sparing preparation, which is the most ingenious thing, that is, leaving the dark preparation of the works visible (indeed: this technique will increase as Caravaggio advances in his painting career).”

According to Vodret, several of Caravaggio’s typical executive characteristics can be found inEcce Homo: “various superimpositions of drafts, visible preparation in some areas, sketches and incisions. These features suggest that this is an original and not a copy (think of the overlays of the loincloth: a copy would never have painted the loincloth in full and then had it overlaid).” There is one perplexity, however, according to Vodret: "the visible preparation is too poor to be a late work as the style says. Looking at the material published by Mina Gregori one can find other important changes to confirm the originality of a painting in general and this one in particular. Gregori, Orlando and Bonavera have identified some changes: the shifting of Christ’s right shoulder, the shifting of the position of the thumb, slight changes on Christ’s hands, loincloth and forearm (although these are not compositional changes: the interesting changes are the compositional ones and not the minor adjustments). Then there are others that in my opinion are more important because they are compositional but should be verified with a new digital X-ray (everything we say today is sub iudice): around Christ’s neck there is a collar (perhaps there was a garment of a different style underneath), the position of the torturer’s sash (which was almost over the eyes), different positions of the cloak (for example, the flap held by the torturer that was quite a bit higher). The work is stylistically late, unrelated to the Massimi competition, and was probably executed in Sicily, soon passed to Genoa where a number of point derivations exist. However, I think it is necessary to rethink the whole stylistic analysis of Caravaggio’s last period."

Notes on the execution technique also came from Claudio Falcucci: “I would not exclude that with a somewhat deeper study of the reflectographic investigation it is impossible to identify a wider network of engravings than what we identify today. Understanding the extent of these engravings is a relevant aspect: the role of engravings in Caravaggio’s career changes considerably (in the early stages we do not have it, in the mature phase it is a crescendo up to 1606 and the engravings seem to represent a complete graphic setting of what the painter wanted to paint, and after 1606 they tend to become very marginal until they almost disappear, while in other cases they come back a little bit but as a rule they are few). Understanding what the actual role of the engravings is might give us indications of compatibility with one period rather than another. On the preparation, reading the reports, it seemed that there was not much preparation to spare. This preparation is normally allowed to shine through by Caravaggio in many areas of the painting, where the color of the preparation responds to the color solution the painter wants to achieve on the surface. On the Hand of Pilate, for example, all the shaded parts were actually obtained with a dark pigment applied over the already made pictorial layers.”

“The reduced presence of engravings,” Falcucci concluded, is “compatible with a late-stage painting, while the lightly weighted role of the sparing preparation is instead something that does not fit with paintings of the late period (1607 onward). The question at this point becomes another: do we not have the saving preparation because perhaps the large number of alterations and repentances means that this preparation cannot be perceived? Or is what we currently see not exactly the state of the painting at the time it was completed? We certainly don’t see the painting as it was when it came out of the artist’s workshop: there must surely have been many traumatic events for the painting (and this one had many), and interventions designed to restore the damage of time. That sort of putty on the inside of Christ’s wrist is symbolic of a mode of intervention that tends to want to restore perfection to the painting. Often the sparing preparation has been seen as an imperfection in the painting, caused either by the painter’s lack of attention, or by the effect of time resurfacing the preparation. The 2003 intervention sought to give legibility to the work and balance to something that had perhaps lost its equilibrium. However, we know that there have been previous interventions, such as that of Pico Cellini.”

After Laura Stagno gave a brief profile of Giannettino Doria, the discussion turned to his hypothetical role as commissioner of theEcce Homo and the possible identification between Pilate and the Andrea Doria painted by Sebastiano del Piombo. A thesis on which Lauro Magnani spoke: "in fact the seduction of the possible connection ofEcce Homo with the Dorias is strong, but in reality if one wants to recognize in the structure of Sebastiano’s painting a possible inspiration for Caravaggio, the way in which he resolves that figure with a Dorian commission is contrasting, because the figure of Pilate, although not a totally negative figure (one would have to analyze the Gospels) can be perceived as such, and then the face is strongly characterized."

TheEcce Homo therefore remains a work that leaves open many questions, and which will still need to be studied in the future: the hope that emerged at the end of the work is that the painting can be subjected to new investigations, according to the parameters of the latest diagnostic campaigns, which may lead to the acquisition of new data to help shed light on some aspects that still remain to be clarified.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.