A participatory museum site. The case of the MAR - Regional Archaeological Museum of Aosta.

Imagine a museum that is easy to understand, engaging for you and yours, requiring no specialized skills to interact with objects and content. Imagine a museum where you would feel comfortable, where you could find answers to varied questions that arise from the content on display, where you could understand possible futures through the stories the museum tells and a selection of curated objects from the past. Does this more experiential type of museum exist? Yes, and it is increasingly growing in the international museum ecosystem.

Museums have always been the places for preserving, preserving and protecting objects, artifacts and works of art for a public to visit, discover and learn about. This is often the case with southern European museum practices, which boast rich collections that, historically, originate predominantly from the same context and cultural landscape as the museum that houses them. Much emphasis has been placed on the content within the museum container. Much less on visitor audiences.

Since the historical vocation of the museum has been to collect and preserve cultural heritage, which it then makes accessible to the general public, an ever-increasing look toward its audience with a human-centric approach would require considerable mental adjustment. Over the past 15 years, "The Participatory Museum" by Nina Simon (2010) has been the reference book for participatory museum design pioneered in person by Nina Simon at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (California, U.S.A.) in her capacity as Executive Director of the museum.

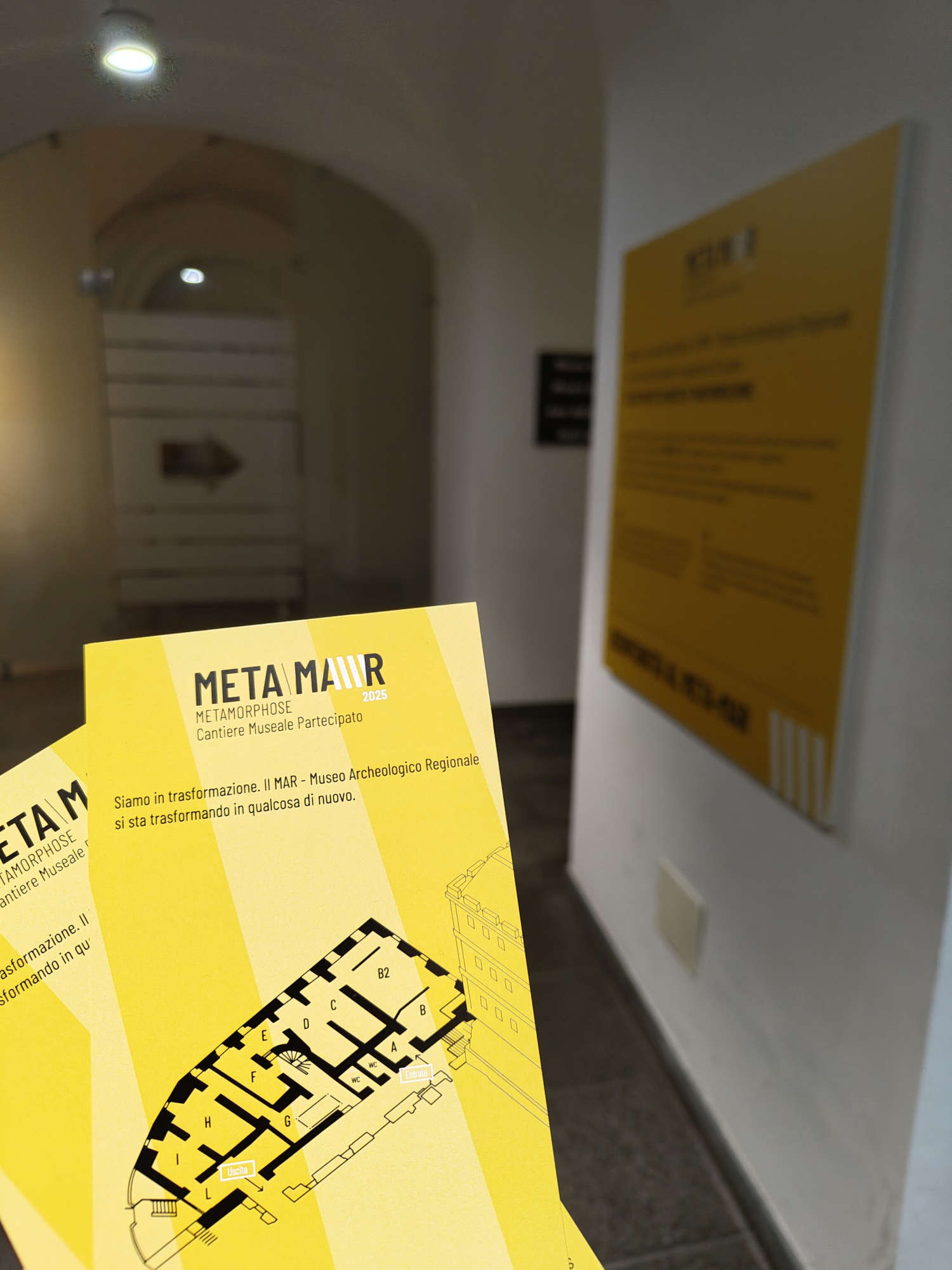

But can we copy and paste, or would there be another way to go? We need to create indigenous solutions that are incubated in the territory itself. This is the case with METAMAR - Metamorphose 2025 - a participatory museum site that is part of the Aosta Regional Archaeological Museum’s redevelopment project. The museum, which has always been open to challenging itself with exhibitions, lectures and educational events that put the museum public at the center, has chosen to take a further step forward.

One could compare the participatory museum site to a toolbox for building a new type of museum, an experimental space or laboratory where new ways of engaging current and future MAR audiences can be developed. In summary, the project aims to find the answer to a simple question: why and what is a museum for? The question is a must but is often not asked.

The path embarked upon by the Regional Archaeological Museum of Aosta (MAR) involves a new exhibit currently being designed with stories to be told through a focused and scientifically sound selection of archaeological artifacts. Instead of closing the old museum, as is usually the case, the Autonomous Region of Valle d’Aosta - Department of Cultural Heritage and Activities (Archaeological Heritage and Monumental Heritage Restoration Structure) has decided instead to transform the museum into an experimental space, similar to the concept of a laboratory, where socio-museum practices can be tried out with the intention of creating indigenous participatory experiences.

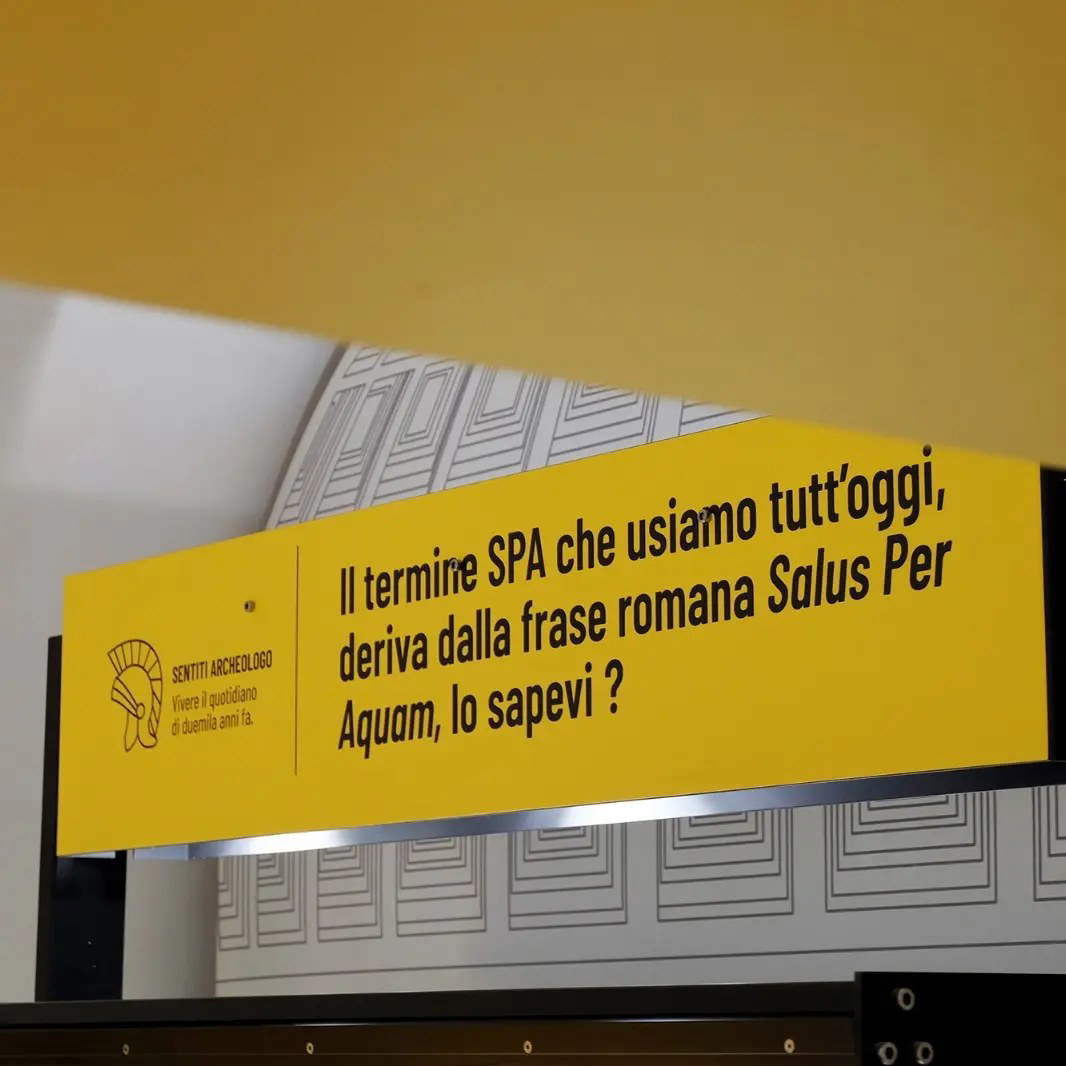

In practice, the tour route of the participatory museum site has precisely the air of an actual construction site with work in progress. Interventions were made on the layout by offering interpretations and educational panels written in simplified language with a choice of content to be communicated intended precisely to arouse curiosity and involvement. The visiting public has before them a choice of communicative and interpretive language to compare that empowers them to compare an experimental interpretive strategy that starts from the question of involvement with the previous more traditional one. In some cases, one tries to go beyond the stimulus question by instead seeking an approach that starts from critical museology by asking, for example, whether the visiting public would feel comfortable in front of human remains on display (this is often the case in archaeological museums). Some spaces have been transformed far more than others by relating visual and textual interpretive material to archaeological artifacts. Others will undergo targeted interventions as the construction goes on until closure next October.

Then there are also “icebreaker” moments for audiences less familiar with the content of an archaeological museum. At the entrance, for example, the visiting public is greeted with a handprint left on the fresh clay of a Roman-period brick, inviting the visitor to relate the two-thousand-year-old imprint to his or her own hand. Next, one of the collection’s prized pieces, a silver bust of Jupiter Graeus, is presented to the visiting public with images of the find’s state of preservation at the time of discovery. The bust, found entirely crushed, was restored to its original state by the famous goldsmith Renato Brozzi (1885-1963), who had Gabriele D’Annunzio as one of his main clients. Thus, an attempt is made to layer the museum experience of involvement by creating modes of enjoyment even for non-expert audiences, helping to break the ice to engage curiosity.

The museum toolbox and toolbox created specifically for this participatory museum building site considers design thinking as one of the essential tools with which we will seek to define ways of engagement for future MAR museum audiences. The use of design thinking by museums is not an entirely new thing, especially for those that are investing more in audience development. In Italy, for example, the Egyptian Museum in Turin used it to create an audioguide already in 2017. In the case of the Aosta participatory museum site, the choice of design thinking methodology comes from marketing understood as the business of promoting and selling products and services. This approach aligns perfectly with the 21st century museum’s need to “sell” usable and engaging museum experiences.

In the coming weeks, as the work progresses, it will be a pleasure to share further insights from the experience of a multidisciplinary team in experimenting and defining the best solutions to the museum to come.

METAMAR - Metamorphose 2025: the participatory museum building site is the result of the work of a multidisciplinary team led by Maria Cristina Ronc, head of MAR at the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage and Activities of the Valle d’Aosta Region to which Gaia Provvedi, Filippo Giustini and Alessandro Rabatti (Marketing Toys SRL), archaeologists Giordana Amabili, Gwenael Bertocco and Paola Alemanni together with Maurizio Castoldi and Alessandra Armirotti of the Superintendence are part. The undersigned is part of this multidisciplinary team in the capacity of museologist and museum thinker.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.