A happy time for Guercino, time for exhibitions and rediscoveries

The Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna offers citizens and international culture an exhibition on Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666). A review toward an anthology of works that place the master at the center of seventeenth-century European painting and, above all, fully echo a glory that never faded along the secular vicissitudes of criticism and transient interests.

A splendid genius of high culture but capable of popular language, the Cento painter with the tantalizing nickname universally personified that satisfying balance between classical metrics and expressive immediacy that was the most generous and most continuously creative outpouring of an all-Emilian strand of art between the 15th and 16th centuries. Such achievement is no secret to scholars who are well acquainted with the gaudiosa source of Emilian painting: a source gushing forth from the heart of the Renaissance that bears the name and deeds of Antonio Allegri. For from Correggio, from his vivid harmonic completeness, his tender tactility, and his cosmic spatial freedom descended a heritage that first imaged the Carraccis and their successors, then Guercino, who declared Correggio an “unparalleled master.” He unconstrainedly picked up the great lesson and added to it his felicitous compositional thinking, along with the preeminent instance of an immediately experienced naturalism and the fragrant freshness of a “country spirit” that makes his works indegradable especially with regard to the pugnacious and vivid dialectic between light, penumbra, and shadow.

This is one among many scenes frescoed by the young painter in the house of a farmer. In it the breath of nature and evident luminosity welcome simple human actions. A fresh and joyful departure on the part of the fervid artist

To introduce its inhabitants and visitors to Guercino, the city of Bologna has already begun cyclical illuminations and itineraries regarding this pictorial genius who has ingeminated the city with more than fifty masterpieces (as he did in papal Rome) and is attracting the full cultural and aesthetic enjoyment of many popular and youthful streams who are willingly increasing their precise interest in the present works and in European figurative arts.

As well, Italian and general artistic attention is happily experiencing a great moment of admiring reappraisal on Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, who was a handsome gentleman of noble bearing, highly educated and limpidly Christian. He was a painter, and a congenital strabismus caused him to be called “il Guercino” as a boy, but he saw well, indeed very well. As we have already written he was born in Cento in 1591 and would end his life in Bologna, after many triumphs, in 1666. Growing up in the countryside, near the gates of his city, he imbued himself with the common sense of simple families, and the immediate and universal contact with nature. Each of his paintings, in fact, carries within it a subdued limpidity, a truth that enters with élan into the soul of the observer, accompanied in the various visions by the powerful atmospheric effect that modulates the vivid light radiated and the powerful shadows gathered in the youthful, tempered days of Cento.

This is our premise, which is well aware of the prodigious gifts bestowed on him by the sky, but also of the compositional study he tenaciously conducted: new, convincing, always effective and totally prehensile with respect to the subject, even in the proposals that most surprise us by the fullness of their full enveloping charm. We know that the coming study season will bring distinguished exhibitions on Guercino, including in Turin and Rome, almost an international embrace of the great master.

This painting-great testament to Guercino’s early maturity-was executed for Cardinal Jacopo Serra, who was certainly impressed by the exceptional compositional mastery and complex luministic articulation. The thesis of the “self-made painter,” and who then remained many years in Cento, holds up to a point.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri’s values are truly astonishing. They struck his first supporters in his hometown, and quickly the Bolognese pictorial milieu in the person of the great Ludovico Carracci, then immediately in the evaluations of wise men and ecclesiastics, with an immediate and pervasive wave of sound fame. Cardinal Alessando Ludovisi, his client in the city of Bologna, becoming Pope Gregory XV, took him to Rome where in two years (1621-23) he won every comparison. Then, highly acclaimed, he worked for Reggio Emilia and Piacenza; he sent works to other cities and places. In 1629 he was honored personally in Cento by the intentional visit of Diego Velasquez-a sensational event. In 1642 he was invited to take his workshop to Bologna, where he worked intensively until his death.

Prominent among the values is the sketching ability, certainly free of any research hindrance, and which makes touching that virtual and immediate figurative mobility that makes the painting a lively dialogue, easy and assumable, for every episode exhibited, religious or profane. The balance of composition, always, even when the presential masses are several. The use of squillant colors, including the beloved blue that distinguishes the master. The mimicry of the characters, corresponding to the Guercino’s identifying heart, devout or lyrical, which enters into the very intimacy of the protagonists of his scenes. Certainly the Exhibition Catalogue reveals the strength of the language and the most sensitive details, which we can confirm from the breadth of its applications.

The election of Cardinal Ludovisi as pontiff opened an airy training ground in Rome for Guercino’s art. Here his skill and freedom as a fresco painter placed him in the forefront, but his stay in the eternal city lasted only two years

After the frescoes in the Casino Ludovisi here is the direct commission from Pope Gregory XV for an altarpiece to be placed in St. Peter’s Basilica. Here the three realms of divine creation are masterfully circulated in one of Barbieri’s most exciting works. Critics have engaged at length on such a santorial poem, and it seems to us that Cesare Gnudi’s overall assumption is relevant: “grand and true forms, of mighty dramatic force, natural and classical.”

Here we can recall the great scholar who extolled Guercino, namely Sir Denis Mahon, a good friend of Gnudi and then of Andrea Emiliani who followed him wisely: we saw him precisely smiling at the 1968 Exhibition right here in Bologna in the same Pinacoteca. In our time the baton has properly passed to Daniele Benati and his School who have deepened the territorial, documentary, contextual, and truly scientific investigations. Following now a chronological trace of Guercini’s works, we can see in part the territorial diffusion they had and the recognition they obtained after the master’s return from Rome. Not forgetting the now famous “Book of Accounts” edited by his brother Paolo (an excellent chiseler in painting), to which document the exhibition opening this October devotes a special Section.

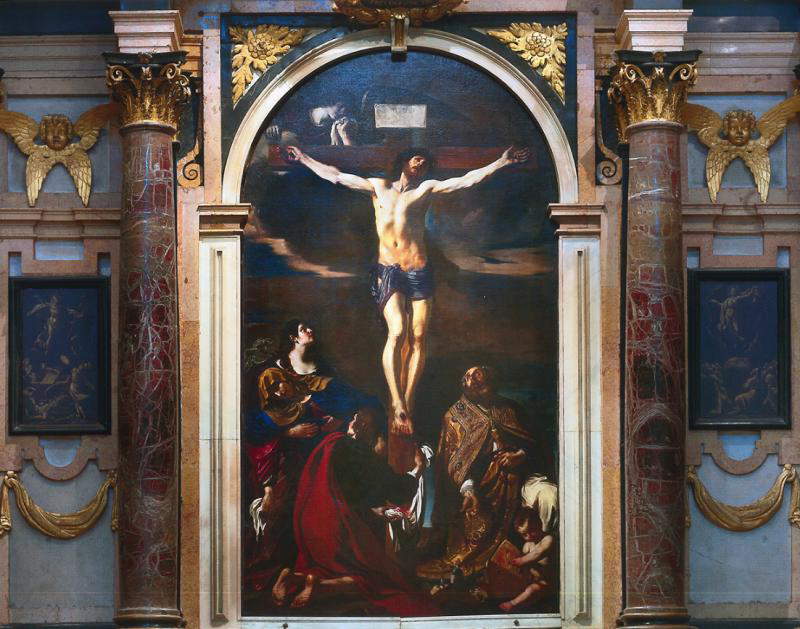

While in the San Lorenzo we still deliberate the musical simplicity of the relationship of a believer who will remain so until his martyrdom, before the Reggio Crucifixion we are overwhelmed in the supreme salvific tragedy of Christ’s death, as are Mary and the Saints mystically placed at his feet, and the weeping Angel. This canvas-a true hapax in Guercino’s corpus-caused a vast commotion among the people of Reggio, who wished to honor its author by adding a gold necklace to the agreed payment

With the six segments of the dome of Piacenza Cathedral, Guercino returned to his youthful and Roman commitments by completing in fresco, as a protagonist, the vault of the Cathedral after the death of the albeit worthy Morazzone. His acceptance demonstrates his inner availability to the works of faith and respect for his colleagues with whom, for that matter, he never had disagreements.

It is the most famous work by the prodigious painter, who here enters the highest measure of his maturity, his creative thinking, and we would like to say the cogent throbs that always accompanied him in his active life as he willed it: a service to the Christian life of every community, of every relative. On the pictorial level, critics place this painting, executed for the “Company of the Most Holy Name of God” in Cento, as a full achievement of the suavity and naturalness that go with the achieved classical form.

Another prized gem in the Pinacoteca Nazionale. Here we see, as never could happen, a martyrdom in the luminous silence of an intimate and angelically abandoned offering

The miraculous apparition that occurred to St. Anthony of Padua in the hermitage of Camposanpiero is caught amid the soft lighting of a newly opened paradise in the dim penumbra of the cell, and here, as never before in Italian painting, the two loving souls meet. Guercino’s brushes seem to smile at the sitting of the nude Jesus above the book, but what theological reality lies hidden there. And our hearts are listening

Another gigantic canvas by the inexhaustible master, who by 1642 had already brought his home and his very capable workshop to Bologna. We are in the heart of the city and the very expensive masterpiece is requested by the Carthusian fathers, whose founder - Saint Bruno - is presented as a model of ardent Marian piety. Our gaze ascends perfectly from the contemplative monk kneeling to the outstretched Saint Bruno, and is caught by the gigantic Angel (a true decisive invention) toward the benevolent Jesus and the resplendent Madonna in the embrace of the blues of divine envelopment. We are back in Bologna and back in the Pinacoteca, ready for the exciting exhibition

We would like to close our solicitation of attention to the art of dear Giovanni Francesco with this splendid figure, once of the de’ Medici, andppointed in London by the enlightened Sir Denis Mahon. The painting is in the last phase of the now universally acclaimed artist. Here we no longer find the blistering conflicts between light and ’shadow, nor even the shading or polished penumbras that have so rattled the most sensitive critics, but a joyful clarity that restores everything where the composition stretches with a purity of high lyrical language into a perfect classical dimension.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.