It was most likely called Alkedo, meaning “alcyone,” the name of a bird typical of sea areas. And it is probably the best known of the Roman ships discovered around Pisa. A large ship made of holm oak and pine wrecked in the first century A.D., a river ship of the imperial era, 12 meters long, whose function is still unknown: it had the shape of warships, but it did not have a spur on the prow, which is why it was likely to be a reconnaissance vessel, a ship that served for patrolling rivers. She was given this name because, on one of the rowers’ benches, the inscription “ALK(E)DO” was found.

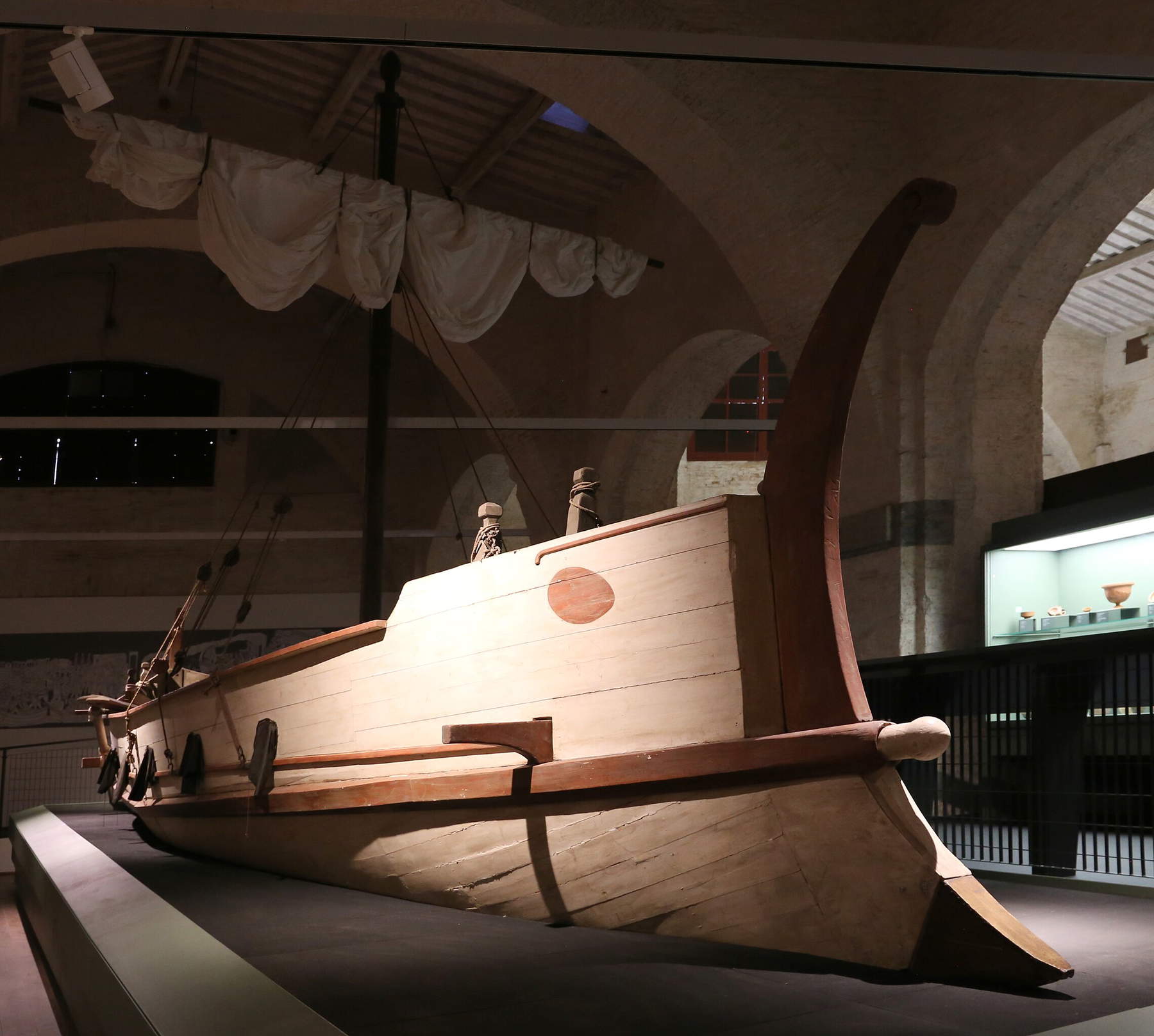

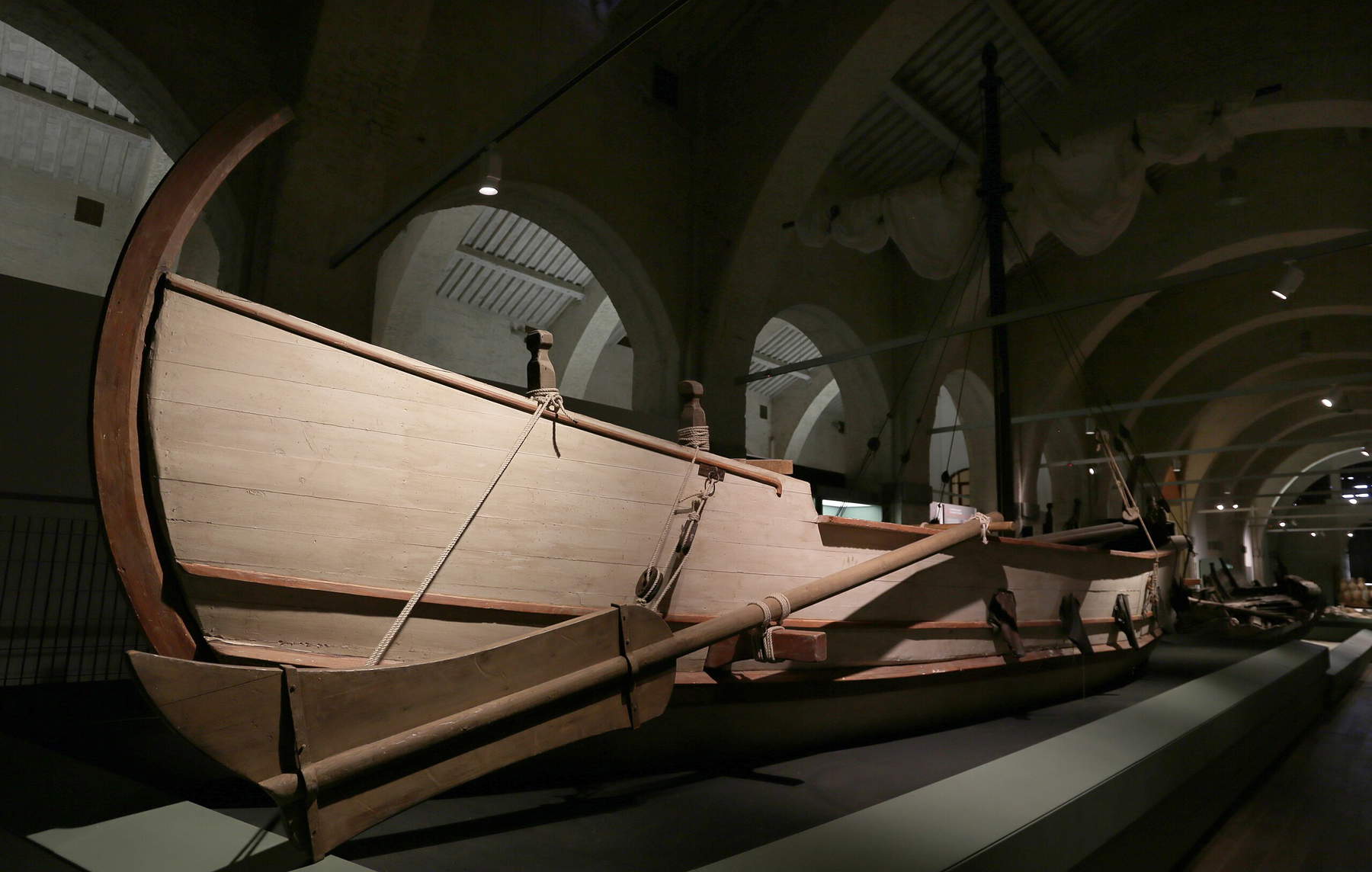

The wreck of the Alkedo is now preserved at the Museum of Ancient Ships in Pisa, a place that holds priceless treasures of the Roman maritime past. What remains of the ship is on display along with a reconstruction of it. The fascinating story of this ship, which spanned two thousand years of history coming down to us, gives us an in-depth look at river life (as well as maritime life) during the time of the Roman Empire.

In 1998, during work on the construction of a control center for the Rome-Genoa railway line near the Pisa San Rossore station, workers came across an archaeological site of extraordinary importance. The excavations uncovered a series of Roman shipwrecks, including the Alkedo, which stood out for its astonishing state of preservation. In addition, the discovery of the name, which is rare for such an ancient ship, gave the vessel a precise identity, suggesting a symbolic link with the seabird known for its speed and agility.

The site, located near the ancient course of the Serchio River, revealed a complex stratigraphy, with thirteen phases ranging from the 6th century B.C. to the 7th century A.D. In particular, the Alkedo belongs to Phase IV (AD 1-15), a period characterized by a great flood that caused the sinking of several vessels. The presence of ships of various types and sizes suggests that the area served as a river port, used for both commercial and military purposes.

The Roman ships of Pisa were found in a geological context that tells the story of the area’s riverine landscape. The city of Pisa in Roman times did not have a proper river port, but alanding area for trade that was regularly affected by flooding, as attested by the presence of numerous layers of sand and clay. These floods, which characterized the history of the site from the 6th century B.C. to the 5th century A.D., were fatal for many ships, including the Alkedo.

The dynamics of the Alkedo’s shipwreck thus turns out to be related to one of these violent floods, which can be dated around the Augustan age, probably in the late 1st century BC or early 1st century AD. Paleoenvironmental studies have provided important indications of the vegetation of the period, showing the presence of plants typical of wet environments, such as alders and deciduous oaks, further confirming the fluvial nature of the harbor. Interpretation of the site suggests that the port was used primarily for commercial purposes. Pisa, due to its strategic location between the Serchio River (the ancient Auser) and theArno, had close ties with the Mediterranean world, as evidenced by numerous artifacts, including Corinthian imports and Etruscan objects. Strabo, the Greek historian, spoke of Pisa’s flourishing trade, and these finds confirm this.

The Alkedo is a ship about 12 meters long, built mainly of holm oak and pine, with an insert of oak in the bow. The choice of these materials was not accidental: holm oak and pine provided lightness and flexibility, while oak, known for its strength, offered greater resistance to mechanical stresses in the front of the ship. The Alkedo’s light, tapered structure, coupled with the presence of twelve oarsmen’s stations (five benches of two, plus two half-benches on each side, a set-up typical of riverboats called hemioliai, small, fast fighting ships of Hellenic origin), indicates that the vessel was designed for speed and agility, features essential for reconnaissance operations , river patrols, and perhaps even the rapid transport of people or light goods.

Another notable feature of the Alkedo is its mast, which must have been supported by six shrouds, and probably supported a square sail about 8 meters wide and 4.5 meters high, with an 8.60-meter flagpole. This element further suggests that the ship was designed for fast and versatile sailing, both rowing and sailing.

In addition, a particularly fascinating aspect of the Alkedo is the presence of traces of red and white pigment on the outer sides, highlighting that the ship was originally decorated in bright colors. These color details not only had an aesthetic function, but could also serve to identify the vessel, represent symbols of membership in a specific fleet or family, or even have ritual or apotropaic meanings, intended to protect the ship and its crew during navigation. The traces of color also allowed for the study of the hull’s caulking techniques, or waterproofing, performed with the use of pitch, rather than the more common resin (which would have altered the paint colors). The ship was also equipped with a bilge pump, which was used to empty the hull of any water.

Artifacts were also found on the ship. Among the most fascinating ones is a pile of leather read by scholar Andrea Camilli as an ancient leather jacket, of a type that was far from fine, perhaps used by a sailor (the fact that it was found as a pile of sheets is due to the fact that its owner, before the ship wrecked, had folded it and stored it probably under a bench): the shape of the garment, which was too bulky to suggest military use and had functional reinforcements, would reinforce the idea that the ship was used for other purposes, such as transporting goods (in fact, the jacket was considered more suitable for a dockworker than a soldier). Other artifacts, such as amphorae of Betica origin for transporting garum (a highly prized fish sauce in antiquity) and wine, further enrich the picture of life on board.

The Alkedo, as mentioned, met its fate during one of the frequent floods that hit the region in the first century AD. The tumultuous waters of the river dragged it along, causing it to sink and subsequently be buried in river sediments. Paradoxically, this very catastrophic event allowed the ship’s extraordinary preservation to the present day. The alluvial deposits created an anaerobic environment that slowed the decomposition process of the wood, preserving much of the original structure. This type of preservation is relatively rare and offers archaeologists the opportunity to study construction details and shipbuilding techniques otherwise lost to time.

The recovery of the Alkedo presented a considerable technical and logistical challenge. Archaeologists had to operate with extreme delicacy to avoid damage to the fragile wooden structure. After recovery, the ship underwent a long and meticulous restoration process, which included treating the wood with preservatives. These interventions were key to stabilizing the structure and preventing further deterioration, allowing it to be displayed to the public. Today, the Alkedo, the “flagship” as she is often called, is one of the most valuable and representative exhibits in the Museum of Ancient Ships in Pisa, and is displayed alongside a full-size replica that gives visitors a complete view of what she must have looked like originally. This presentation allows visitors to appreciate not only the size and shape of the ship, but also to better understand its construction techniques and functionality.

The Alkedo ship is an extraordinary window into ancient Rome, a testament to the river and commercial life of a bygone era. Its restoration and preservation have enriched Pisa’s archaeological heritage, providing us with a fundamental object of study for learning about ancient Roman seafaring. Its presence in the Museum of Ancient Ships in Pisa represents a tangible link to a world that, though distant, still speaks to us through the wave-worn wood and the artifacts left behind by those who sailed along the river waters of ancient Rome.

|

| The ship Alkedo, the flagship of the Museum of Ancient Ships in Pisa |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.