In Florence, the Museo di San Marco is housed in the convent of the same name, amidst the charms of a place steeped in spirituality and the memory of illustrious members, such as Friar Girolamo Savonarola or Beato Angelico, and places its collection within the rooms where the brethren lived for centuries. The complex, which also consists of the adjacent basilica and library, has over the centuries become a center of culture as well as art.

The convent of St. Mark was founded on March 8, 1299, by monks of the Benedictine Silvestrine congregation, but as early as 1250 sources indicate the pre-existence of an oratory, later granted in 1290 to the monks to build their convent; traces of the building’s life during this period remain in some fragments of frescoes. The convent and church of San Marco Nuovo, so called to distinguish it from the church of the same name in San Marco, were soon claimed as a seat by the friars of the Dominican order, whose prestige was growing day by day, and for this reason, in 1418, under the pontificate of Eugenius IV, the Silvestrines were obliged to abandon the church and monastery, which they sacked, however, carrying away and destroying all kinds of furnishings. The buildings, left to the Dominicans in very poor condition, needed major restoration, for which the architect Michelozzo di Bartolomeo Michelozzi, a pupil of Brunelleschi, was commissioned in 1437 by Cosimo de’ Medici.

The consecration of the new rooms took place on January 6, 1443, in the presence of the pope. In addition to the construction of the upper floor to make the friars’ cells, the creation of two cloisters and two refectories, and a major restoration of the church, Michelozzo’s most emblematic work within the San Marco complex is surely the library: one of the first open to the public, which housed illustrious humanists such as Agnolo Poliziano and Pico della Mirandola. In the spring of 1490 Fra’ Girolamo Savonarola, who delivered his famous orations full of prophetic messages even within the walls of San Marco, was assigned to the convent. The first expropriation of the convent took place in 1808, during the Napoleonic period, and it returned to the friars’ hands only after the fall of the emperor, but they were driven out again in 1866, when the Italian state also decided to suppress religious orders. The convent then was restored and reopened as a museum in 1869, after a refitting and restoration of the Beato Angelico frescoes by the painter Gaetano Bianchi. The extraordinary collection of works by Beato Angelico was increased thanks to Giovanni Poggi, then director of the Uffizi, who brought several works from the Florentine collections to the San Marco museum.

Beato

Beato

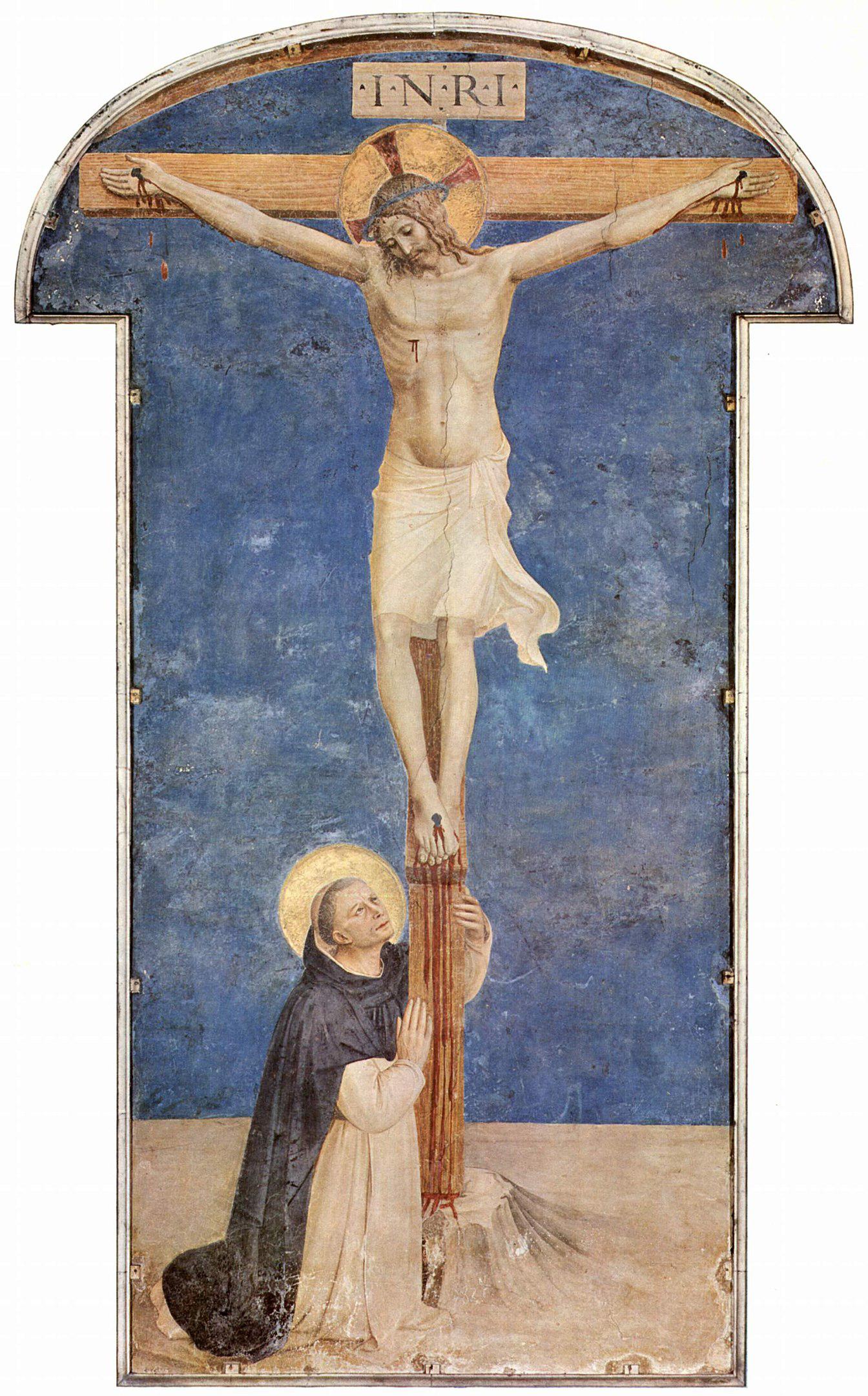

The first room one encounters when visiting the museum is the cloister of Sant’Antonino, built by Michelozzo around 1440, where we find a magnificent 19th-century cedar tree in the center of the garden. The loggia, made of white lime and pietra serena, has five columns on each side, topped by elegant Ionic capitals. The second floor, visible from the cloister, is studded with small single-lancet windows each belonging to a cell. In front of the museum’s entrance we find the Crucifixion made in 1442 by Beato Angelico, until the 17th century the cloister’s only decoration, which depicts the order’s founder, St. Dominic, embracing the cross, emphasizing one of the order’s cardinal principles, namely its close relationship with Christ and its devotion to him. Around 1650, when the Fabroni family became owners of that part of the cloister, the fresco was framed in a marble frame, around which the Florentine painter Cecco Bravo painted complementary figures, including the Virgin and St. John the Baptist. In the cloister, Angelico also made five lunettes, depicting respectively St. Peter Martyr enjoining silence, St. Dominic showing the rule of the Order, St. Thomas Aquinas with the Summa, Christ the Pilgrim welcomed by two Dominicansand Christ in Pity; originally placed on the cloister doors, now moved inside for conservation reasons.

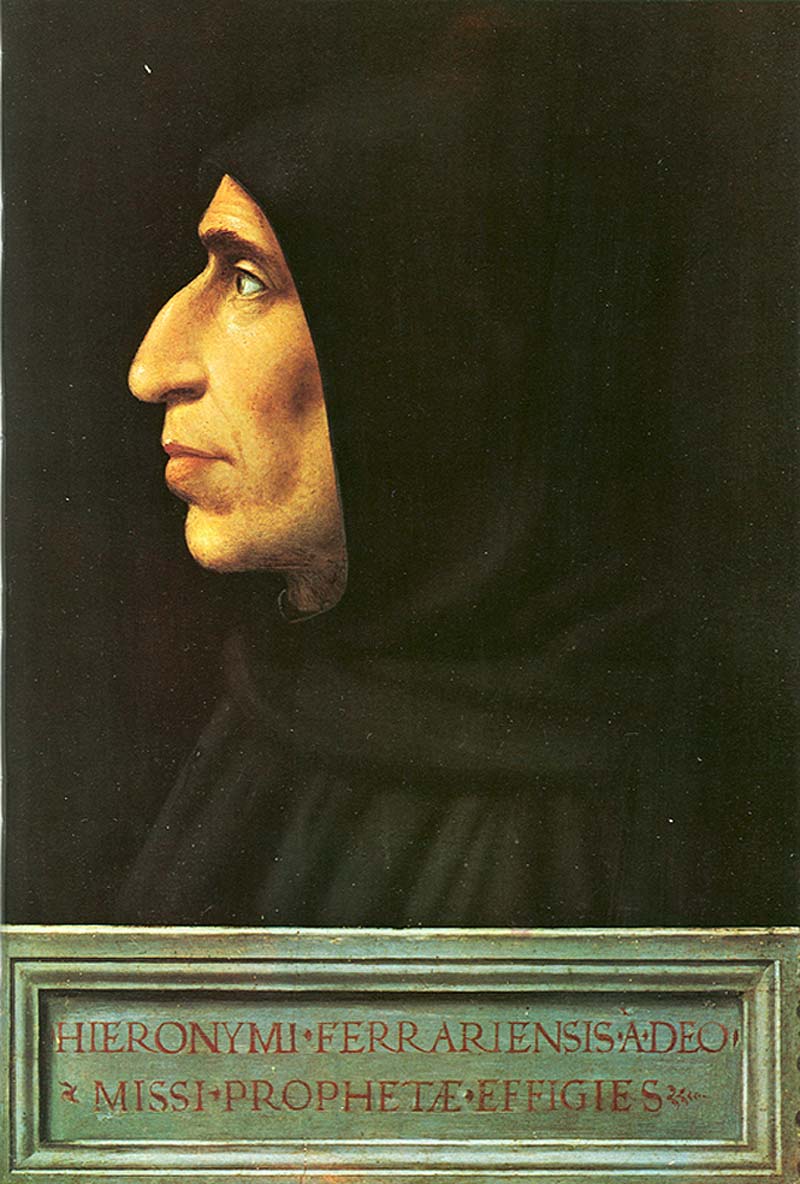

In the seventeenth century, to celebrate the figure of the Dominican to whom the founding of the convent was attributed, St. Antoninus, a cycle of lunettes with Scenes from the saint’s life was commissioned, on which various artists worked, including Bernardino Poccetti. In the lunette where Saint Antoninus elected bishop of Florence is depicted, we see anachronistically depicted Friar Girolamo Savonarola, an indication of the importance the friar had for the order and the convent.

From the cloister is accessible the Pilgrims’ Hospice, a room that already existed at the time of the Silvestrini, where traces of early 14th-century wall decoration have been found on the walls. It is currently the room dedicated to Beato Angelico, particularly his altarpieces, where we find the Triptych of St. Peter Martyr, one of the artist’s earliest documented works, around the 1520s, and the very special Armadio degli Argenti, commissioned by Piero de’ Medici and made around the mid-15th century, a pictorial cycle with scenes from Christ’s childhood, adult life and the Passion made on square compartments that formed the doors of a closet. Also finding its place in the hospice premises is the Madonna Enthroned, or Annalena Altarpiece, which came to St. Mark’s after the suppression of the monastery of St. Vincent of Annalena. It is probably the altarpiece commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici for the family chapel dedicated to the Most Holy Cosmas and Damian, given the presence in the work of the two patron saints of the Medici.

Through another door in the cloister, it is possible to enter the Washing Room, which owes its name to the rite of purification of the hands performed by the monks before meals, as required by the Rule. Above the entrance door a fresco of Christ In Pieta, attributed to Fra Angelico, is extremely deteriorated. Today, the room contains works by artists who lived in the 16th century, such as Baccio della Porta, better known as Fra’ Bartolomeo, whose fresco with the Last Judgment, left unfinished and severely damaged by a move in 1657, and frescoes on terracotta, such as the one depicting Madonna and Child, can be seen in one of the sweetest depictions of the mother-child relationship, perhaps inspired by Raphael’s Madonna of the Chair, the artist models the figures through the use of skillful chiaroscuro. The spacious Refettorio Grande, reached from the Sala del Lavabo, displays numerous works by Giovanni Antonio Sogliani, Fra’ Paolino, a pupil of Fra’ Bartolomeo, and works from the Scuola di San Marco. Now an exhibition space, Fra Bartolomeo’s Room was the former kitchen of the monastery. The painter, who kept a studio in the building until his death in 1517, created very special frescoes on tiles, an example of which is Ecce Homo, painted in 1501. The friar also made two portraits of Girolamo Savonarola, whose great admirer and follower he was, ten years apart.

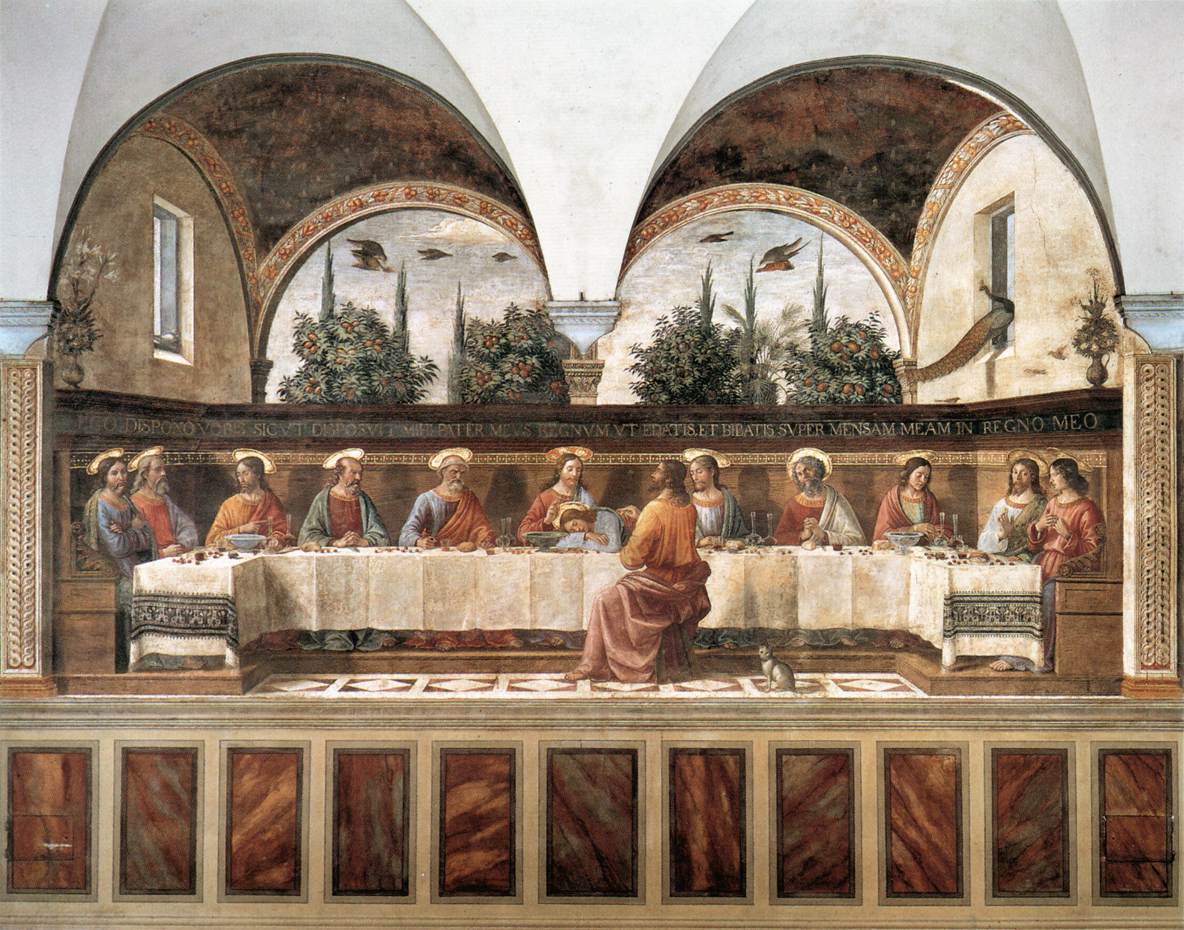

The small refectory houses the grandiose Last Supper made by Domenico Ghirlandaio, some forty years after the monastery was built, and is now a display place for Andrea della Robbia ’s work in glazed terracotta. Connected to the hall by a corridor, the Spesa courtyard, part of the 1440 renovation by Michelozzo, leads to the underground rooms. The underground rooms of San Marco preserve a very rich collection of artifacts that were saved from the demolitions perpetrated in the late 19th century in the center of Florence, decorated elements, detached frescoes and wooden elements. The director of the then newly established museum, Guido Carocci, worked to collect and catalogue this heritage. The artifacts were stored in the ’’guest quarters’’ of the convent, where they still are, and in the cloister of San Domenico, from which they were later moved to the museum’s basement in the Lapidarium.

Beato

Beato

A very important place for the community was the Chapter House, as this was where the Rule was collectively read, part of the 14th-century structure of the building. Above the entrance door is the Crucifixion painted in 1442 by Beato Angelico, unfortunately not perfectly preserved, due to the deterioration of pigments that led to the transformation of the background color from blue to gray. Also preserved in the room is the bell attributed to Michelozzo called “la Piagnona.”

On the second floor is the dormitory, reached by a flight of stairs, probably built in the 17th century to replace the original spiral staircase, which led directly in front of Beato Angelico’s Annunciation, one of the three frescoes painted outside the cells, also frescoed by the friar between 1437 and 1444, in front of which the friars gathered to recite common prayer. The main theme for the decoration of the cells is the Life and Passion of Christ . Reserved for the novice friars, the seven cells decorated with variations of St. Dominic adoring the crucifix are, thanks to stylistic features, probably attributed to Benozzo Gozzoli . At the end of the novices’ corridor is Savonarola’s cell, which was presented with the new layout created in 2021, with the acquisition of the painted terracotta bust made by Mattia della Robbia between 1497 and 1512, the only statue depicting the friar. Also on display are relics related to Savonarola, such as his cloak, or the wooden crucifix from the late 15th century traditionally considered to belong to the friar.

The convent’s library, its flagship, was financed by Cosimo de Medici, who purchased the great collection of Greek and Latin classics of the humanist Niccolò Niccoli. Today stripped of its volumes that migrated to the Biblioteca Nazionale and the Biblioteca Laurenziana after the suppression of the monasteries in the nineteenth century, it is revealed in its bare architecture; the library hall is divided by two Ionic colonnades into three naves , the lateral ones of which are covered by barrel vaults while the central one by cross vaults. Currently on display in the library is a selection of illuminated liturgical manuscripts, part of the collection of 15th-century illuminated manuscripts still belonging to the library.

Adjacent to the monastery is the stupendous basilica of St. Mark’s, with its neoclassical façade, consisting of a single nave and retaining the dimensions of the 14th-century hall, where there were frescoes by Pietro Cavallini, no longer visible except in fragments. It was the work of Giambologna for the renovation that took place in 1588. The side chapels, designed by the architect, are extraordinary, especially the Salviati Chapel, where the remains of the founder of the convent are kept, which features wall decoration by Giambologna’s workshop. Inspired by this is the Serragli Chapel, or Chapel of the Sacrament, where the decoration revolves around the theme of the representation of the gifts of the holy spirit, with works by Santi di Tito and Bernardino Poccetti. In the second and third chapels on the left rest the bodies of humanists Pico della Mirandola and Agnolo Poliziano, who were frequent visitors to the convent and especially its library.

The St. Mark’s Museum can be reached by train, getting off at Santa Maria Novella Station, from which you can take the bus (lines 7, 10, 31-32, 33), while on foot the Museum can be easily reached from the station in 15 minutes. Information on ticket prices and schedules can be found on the official website of the Florentine State Museums ticket office.

|

| The Museum of San Marco in Florence, the former convent of Beato Angelico |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.