The history of the long relationship between man and animal in the Anatomical Veterinary Museum of Pisa

When Caspar Friedrich Neickel published his treatise Museography in 1727, sanctioning for the first time the use of the term for museological sciences, he meticulously listed the museums, studies and collections found in Europe in the extensive directory that accompanied his book. Of these, of great importance, if not pre-eminent, are the scientific museums, which respond to the taste for encyclopedic knowledge and the new conceptions that the Age of Enlightenment was propagating. In our contemporary times, however, science museums, except perhaps those of natural history, do not seem to generate the same enthusiasm. Yet their importance should not be questioned, for not only do they often contain relics that evoke discoveries and theoretical formulations, but they also stand as a bridge between scientific and humanistic cultures. These instances are frequently found in university museums, which began as educational appendages and are now custodians of valuable records of the study of science over time. The Veterinary Anatomical Museum of the University of Pisa is a plastic demonstration of this.

Located within the Department of Veterinary Sciences, the museum was created with the primary purpose of documenting the anatomical peculiarities of domestic animals, particularly mammals bred by humans for economic purposes. Although it is difficult to determine precisely the year of its founding, the museum was a silent witness to thebeginning of the history of veterinary medicine in the University of Pisa. As early as the 18th century, a number of scholars in the field of hippology, the science related to the study of the horse, had distinguished themselves in the city of the Leaning Tower. However, it would have to wait until 1818, when Vincenzo Mazza of Bologna, a former veterinarian in Napoleon’s Grand Army, decided, after the fall of the Emperor, to open a private school of zooiatry in Pisa. Despite the prestige of the practice, which involved important figures such as chemist Giuseppe Branchi and botanist Gaetano Savi (moreover, a key figure in the affairs of the museum and botanical garden of Pisa), its history ended in 1821.

A good 18 long years would pass before, in 1839, Melchiorre Tonelli, a municipal veterinarian and attaché to the Cavalry and Imperial Horse Breeds, gave birth to the first chair of zooiatry, aggregated to the Faculty of Medicine and Surgery of the University of Pisa. This experience too would fail in 1851 with the suppression of the chair. But in 1859 the government decided to form an agrarian-veterinary section, linking it to the University’s Faculty of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, finally starting the Chair of Veterinary and Pastoral Science.

In 1874, with the introduction of new disciplines, the study became enfranchised from the agricultural sciences and was established as an autonomous structure in the Royal High School of Veterinary Science. In this new space anatomical preparations, or parts obtained from the dissection of a cadaver and processed for preservation, collected over these long years of which the oldest date back to Mazza’s teaching, are organized. Thus was in fact born the first embryo of the Veterinary Anatomical Museum, which would be greatly enriched with new preparations, particularly in the period between the 19th and 20th centuries.

However, this influx is curbed in the new century by the use of formalin to preserve anatomical pieces, thus making the use of the preparations obsolete. Added to this, unfortunately, during World War II the necessary care for the preservation of the models was neglected and the exhibits suffered damage, perhaps even due to vandalism, with the loss of part of the important holdings. In 1965 the museum was moved to the new Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Le Piagge, where it is still preserved today.

Today, a visit to the museum offers an experience of rare suggestion, as it is distributed in one vast room, filled with ancient wooden showcases dating back to the end of the 19th century, restoring the atmosphere of a museum standing still in time, in a sort of musealization of the exhibits. No less than 900 animal exhibits are preserved inside, belonging to species that humans have used or accompanied throughout their history, such as farm, companion and transport or pack animals. The most featured species is the horse, which has played a key role in the development of civilization in various fields throughout human history.

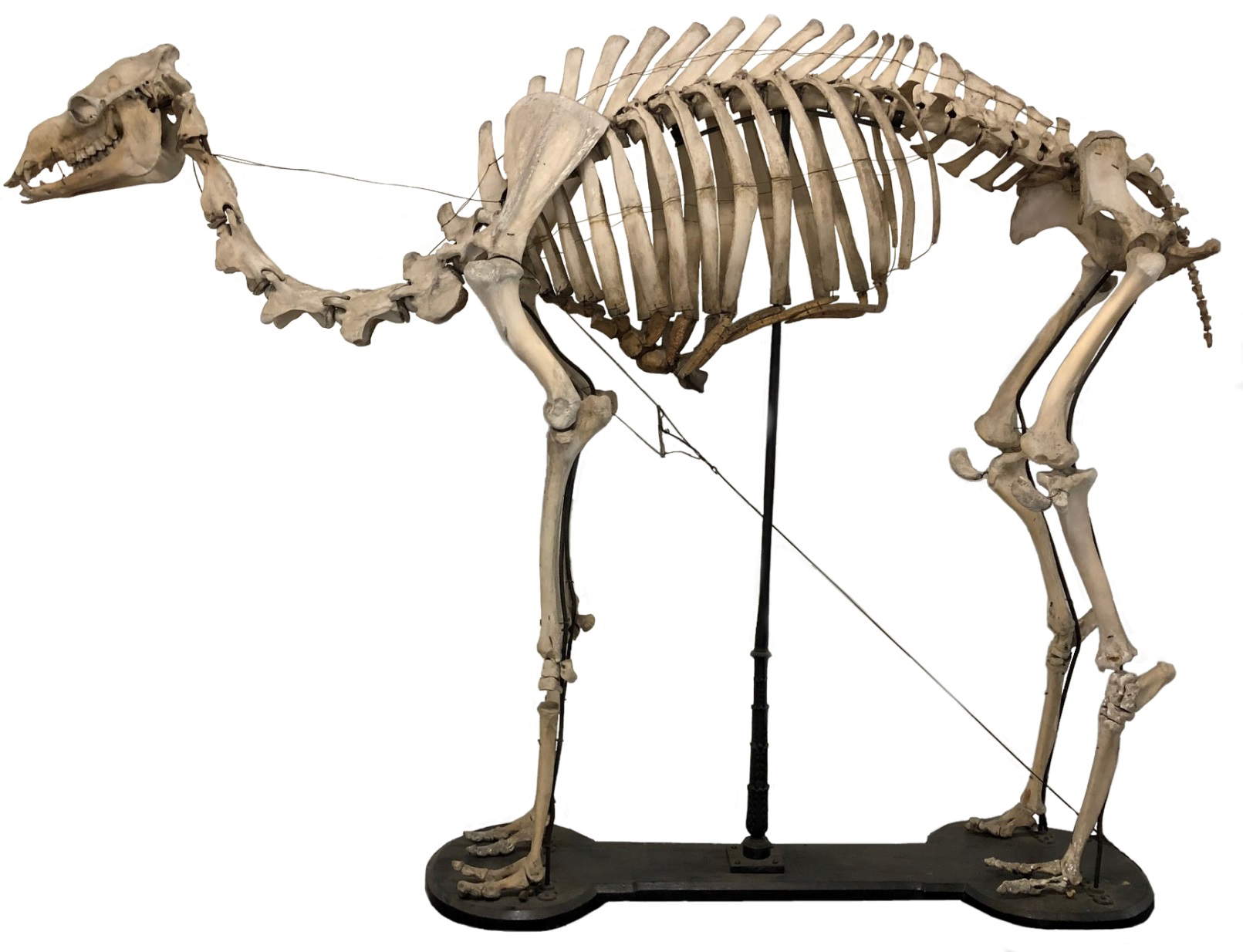

Welcoming visitors from their first steps into the museum are complete skeletons of large animals. Skeletons, now as then, were prepared in various ways: the natural way, in which the body was allowed to decompose underground, or through an artificial procedure, which involved boiling the carcass and thus bleaching the bones.

In the Pisa Veterinary Museum, complete skeletons include those of horses, cattle, as well as specimens of the cervid family, generally belonging to the fauna that thrives on the San Rossore estate near Pisa. From this very location come the remains of dromedaries. The herd of "camels," as they were commonly known and as Gabriele D’Annunzio also recalls them in hisAlcyone verses, apparently arrived in Tuscany as early as the 17th century as a gift intended for the grand ducal family. As they acclimatized, they were later refreshed for use in agricultural work as well, growing to about 200 in number. Unfortunately, during World War II they were victims of neglect and used as cannon fodder by German troops; they became extinct from the park for good in the 1960s. In recent times, however, some specimens have been reintroduced. Two dromedary skeletons, one adult and one cub, as well as other extinct exotic animals are preserved in the museum.

Among the different collections is the cranioteca section, where the skulls of numerous animals, including dolphin, buffalo, tiger and human, are arranged, allowing for immediate comparisons. Also of interest is the preparation of the exploded skull, that is, disarticulated into all its component sections. This technique is performed by various methods, one of the most common being to place bean or pea seeds in the animal’s occipital hole and then plug the cavity with a moistened cork. The seeds, as they sprout, exert pressure and separate the bones in a natural way without affecting the anatomy of the bones.

The collection of teeth from carnivores, equids and ruminants is also significant, as, depending on the state of wear, the age of the specimen can be derived. In the showcases, the specimens, often fitted with their ancient cartouches, are classified according to the apparatus to which they belong. A large showcase contains large hollow organs from the digestive system of various animals.

The insufflated preparations see the organs placed on metal supports and then filled with air and allowed to dry in place. This allows the organ to be shown in its true size, such as the entire small intestine of large herbivores retaining its morphological characteristics. Fundamental in the past were forelimb and hindlimb preparations for the study of animal podiatry, which was necessary for a society that found animals to be the main means of transportation and labor force in the fields. These preparations highlight skeletal systems, ligaments and joints, arteries and veins, and numerous other aspects.

A rich selection of hearts of various animal species is on display in the museum, some presented in sections and prepared by the insufflation or injection technique, which involves the insertion of wax and arsenic to consolidate the arterial and venous vascular system, while externally they were coated with colored pigments.

One of the rarest collections is that of placentas, largely from cattle and small ruminants. But perhaps the most amazing piece is the remarkably large dromedary placenta, which shows the maternal-fetal circulation and umbilical cord. Another rarity on display in the museum is the teratological collection, named after the science that studies alterations in the genetic makeup that cause malformations that change the normal anatomical and functional structure of organs.

Other exhibits show the head-neck-chest complex, making visible the skeletal system of animals, the musculature and the location of certain organs, while still others display the reproductive system, shown isolated and preserved in various ways or included in larger complexes identifying multiple body regions.

Still numerous collections are used for educational purposes in the past, but they continue to provide useful support for study and are still of interest even to the visitor unfamiliar with the subject.

The museum also has an educational laboratory for students of all ages, where, through the comparison of skeletal parts, skull or limbs, it is possible to identify and show the interspecific differences between various animals, as well as the relationship between the domesticated animal and its wild ancestor. In addition, the visit is made more accessible by an online audio guide, which can be accessed via phone or tablet, allowing visitors to independently enjoy the various museum collections.

Although the Veterinary Anatomical Museum of the University of Pisa has specific collections that are not always easy to read, thanks to the suggestion of its spaces stopped in time and the multitude of artifacts of high scientific and educational value, also capable of telling historical and cultural aspects of our past, it manages to have great charm and interest, demonstrating theinextricable relationship that has always distinguished our civilization: that between human beings and animals.

|

| The history of the long relationship between man and animal in the Anatomical Veterinary Museum of Pisa |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.