It is housed in a large building designed by Ticino architect Mario Botta, set in a beautiful park, the Solitude-Park, overlooking the bank of the Rhine. It is the Tinguely Museum in Basel, one of the most unique museums in Switzerland, entirely dedicated to the extraordinary figure of Jean Tinguely (Fribourg, 1925 - Bern, 1991), a great Swiss artist close to the Dada movement and kinetic art, famous above all for his machine-sculptures with which he criticized automation, mechanization, and consumerism. In two words: modern society.

The museum housing Tinguely’s works came into being in 1996 at the behest of the multinational pharmaceutical company Roche, whose headquarters are a stone’s throw from the Tinguely Museum and who financed the operation, and houses the world’s largest collection of works by the Swiss artist. The Tinguely Museum, however, probably could not have come into being without the fundamental contribution of Niki de Saint-Phalle (Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1930 - La Jolla, 2002), Tinguely’s wife since 1971, who in 1992, soon after the artist’s death, donated fifty-two works from her collection, thus establishing the preconditions for the museum to arise. Since that date, the collection has been steadily enriched (Roche also contributed a donation of Tinguely’s works in his possession), thanks to bequests, donations, and acquisitions, and today it is one of the most visited museums in the country, capable of attracting a very diverse audience, given also the highly engaging nature of its displays. The museum houses artworks belonging to all stages of Tinguely’s career, in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the artist’s life and career. There are the fascinating sculptures, which captivate the public by often requiring their participation (they are in fact operated by visitors, or can be walked and climbed), there are drawings, letters, documents, exhibition posters, and photographs.

The museum thus allows for an unforgettable itinerary through Tinguely’s work. The artist, trained in Basel and then raised in Paris where he frequented the avant-garde movements of the time in the 1950s, had introduced himself to the art world in the very early 1950s with the intention of revolutionizing that “static” environment by presenting, on the contrary, works capable of movement, made with everyday materials: iron and wire, steel, tin, industrial paint and much more. Thus were born abstract works that moved through mechanisms devised by the artist himself, which could be operated simply by pressing a switch. His debut was in 1954, when Tinguely exhibited his first ... motorized sculptures, which he called Méta-mécaniques. And it is from here that the museum’s itinerary begins: the first works visitors find are his peintures cinétiques, abstract paintings with elements capable of moving through hidden mechanisms, with the result that the works were always different and unique ( continuous change is one of the theoretical assumptions that animate Tinguely’s work: this is why the artist chose the name Méta-mécaniques for these works). It was also a way of responding to a problem particularly felt by the artistic debates of the time, that concerning the relationship between the work and the space: Tinguely proposed his own solution, making the movement in the works become real movement, movement in its own right.

|

| The Jean Tinguely Museum in Basel |

|

| The Méta-mécaniques |

|

| Jean Tinguely, Ballet des pauvres (1961; Basel, Tinguely Museum) |

|

| Jean Tinguely, Plateau agriculturel (1978; Basel, Tinguely Museum) |

|

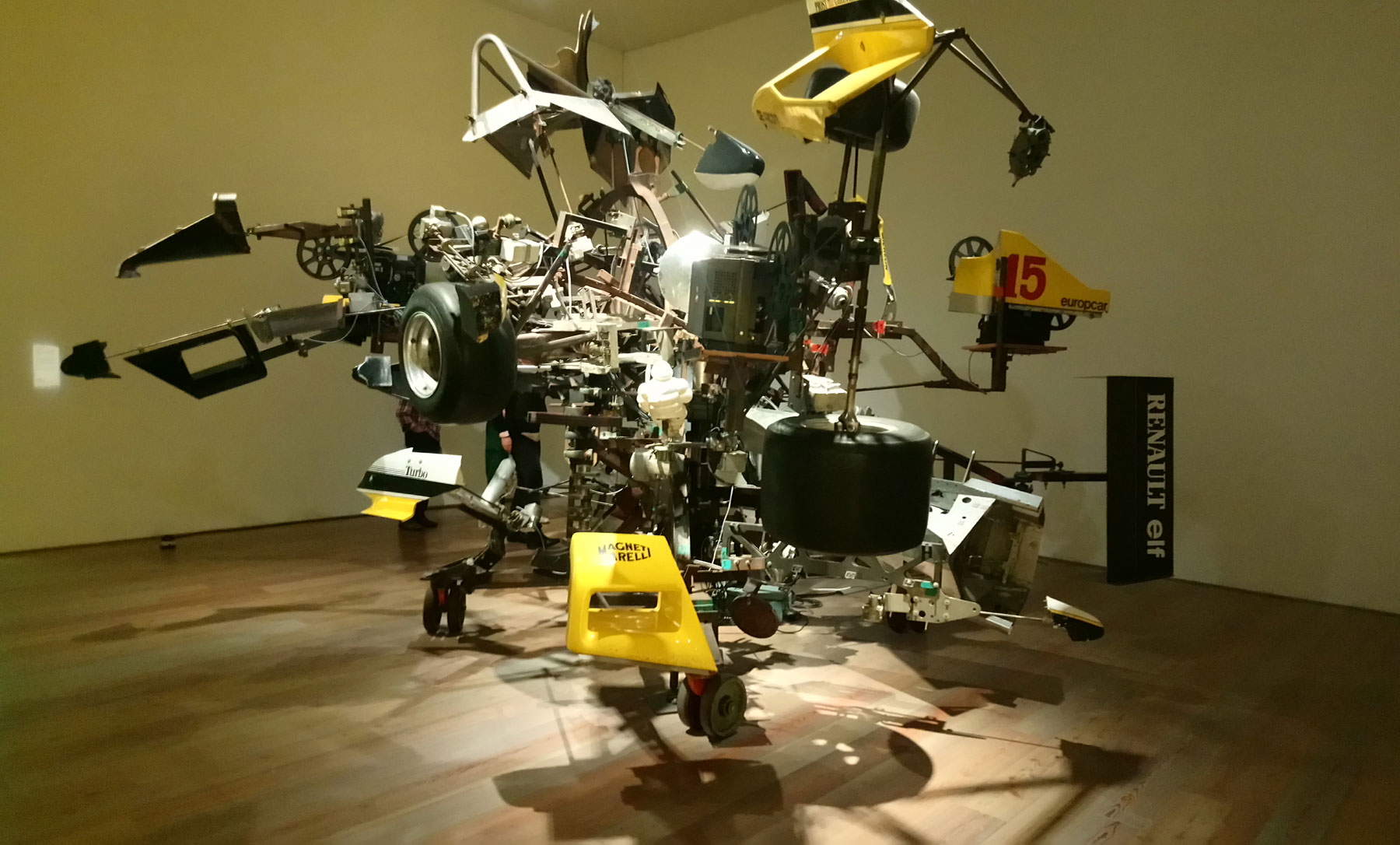

| Jean Tinguely, Pit-Stop (1984; Basel, Tinguely Museum) |

|

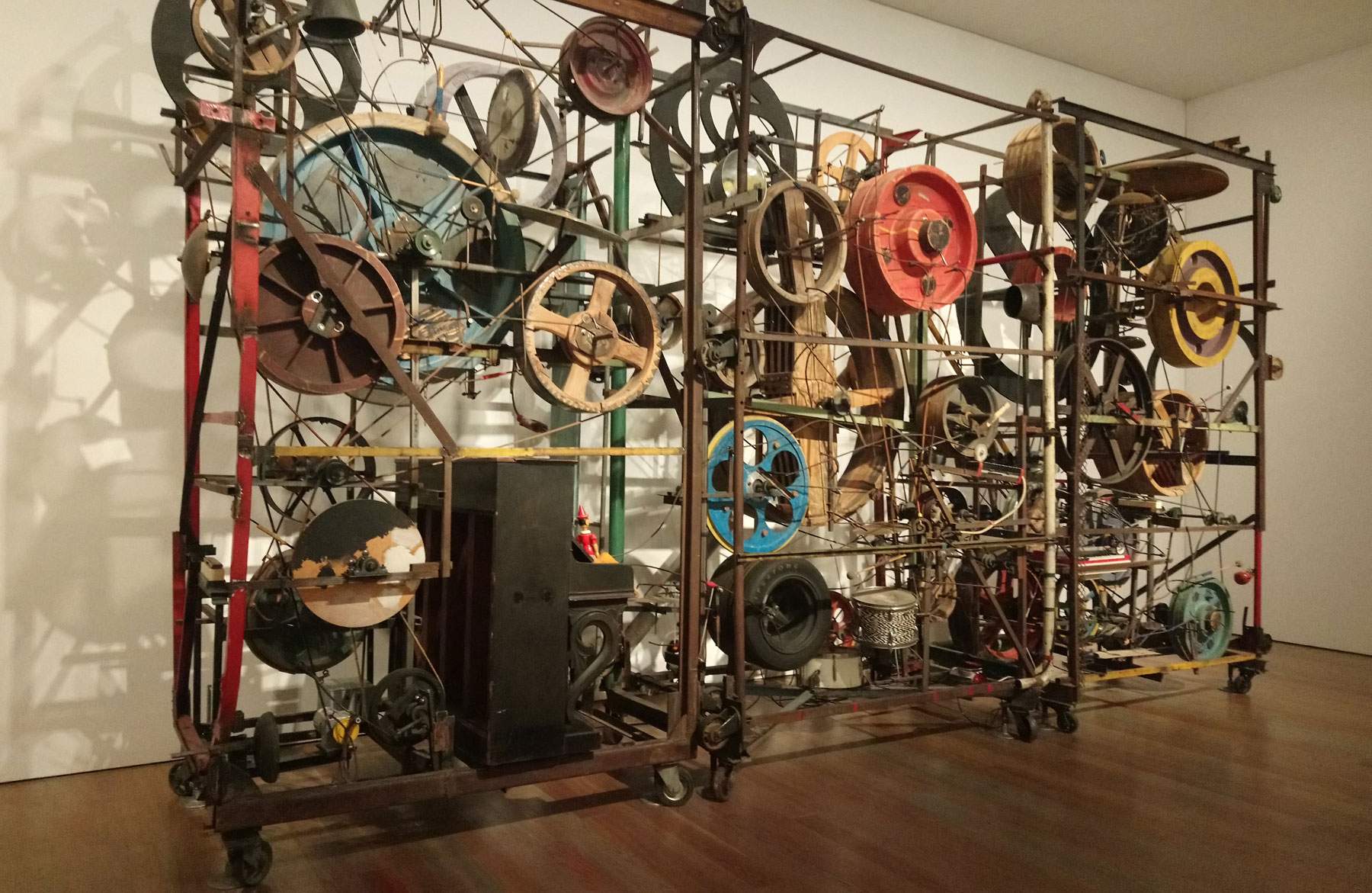

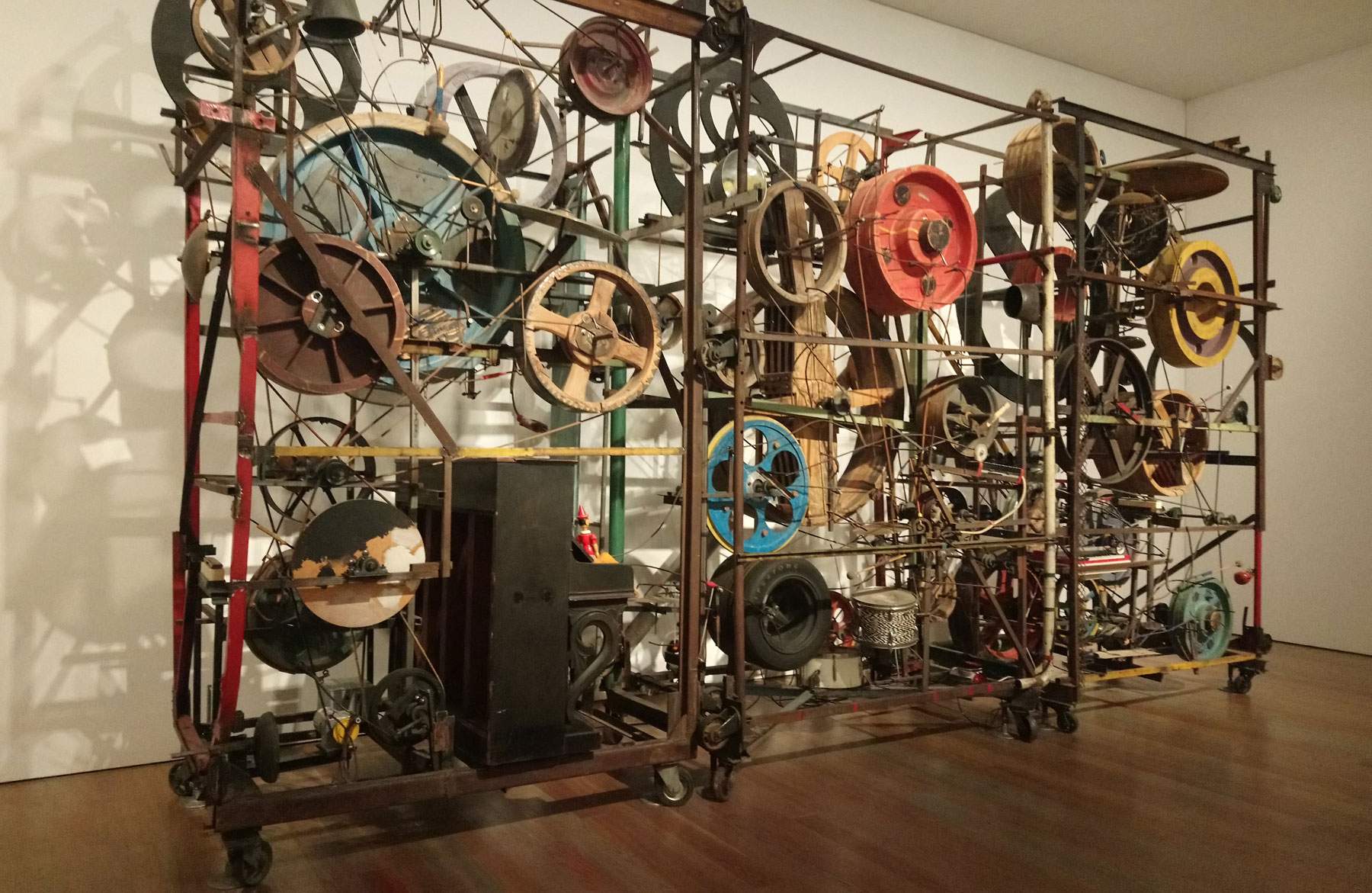

| Jean Tinguely, Méta-Harmonie II (1979; Basel, Tinguely Museum) |

|

| Jean Tinguely, Grosse Méta-Maxi-Utopia (1987; Basel, Tinguely Museum) |

Another topic that Tinguely felt was that of thetotal work of art, a work that could engage all the senses. In this case, his response was the Reliefs méta-mécaniques sonores, presented for the first time in 1955: these are works that, in addition to movement, also add sound, in response also to a need that arose from his exchanges with Yves Klein (an artist with whom he was in a fruitful and friendly relationship: in 1958 the two also exhibited together, and a section of the museum is devoted precisely to their relationship), namely that of “dematerializing” the work of art. This can be seen, for example, in the work Mes étoiles, black reliefs (with white moving elements) that play, but without it being clear where the sound comes from.

The journey continues with works from the 1960s: in 1960, the artist traveled by ship to New York for an exhibition at the Staempfli Gallery. For his stay, however, he also imagined a self-destructing installation dedicated to the city of New York. He managed to convince the director of MoMA (there he wanted to show his sculpture-performance) and, after three weeks of work, presented his work before an audience of three hundred people. “The intense life of this machine is the cause of its self-destruction,” the artist had this to say. It was a positive destruction, however, since the various elements of the work that dematerialized gave rise to a spectacle capable, again, of engaging all the senses. Thus belong to the early 1960s works in which destruction becomes part of the process: heavy, noisy machines, often made from waste material, resulting from the destruction of other objects, which, however, gave rise to a new life. “I love the rebirth of found objects,” he said, “reinventing them to give them a new form of existence in a new dimension.” Tinguely, an admirer of Duchamp, thus proposed his own interpretation of the poetics of theobjet trouvé, with works such as Ballet des pauvres (a hypnotic dance of found objects among garbage) and the Balubas series, motorized sculptures also made from found materials.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Tinguely returned to sculpture, with works that presented themselves to the viewer in a thick black blanket, but this was a transitional phase, because again beginning in the 1970s, when his works began to enjoy great success worldwide, the Swiss artist returned to his bizarre machines, which became increasingly spectacular, often embodying symbolic motifs (this was especially the case from the 1980s onward: elements referencing delicacy and aggression, life and death, male and female), and always marked by the ironic charge that never abandoned his production. There is no shortage, however, of more humble works: thus we go from Pit-Stop, a 1984 work commissioned by the car manufacturer Renault, a sort of ode to the bond between man and machine, to Maschinenbar, small toy-like sculpture-machines capable of referring to different moods and states of mind, from the large sculpture Méta-Harmonie II of 1979 (which is operated at cadenced times given its size), to the great masterpiece of 1987, the Grosse Méta-Maxi-Utopia, a huge machine that the artist designed for an exhibition at Palazzo Grassi in Venice, a kind of poetic celebration of life, a utopian dream world, imagined with the express intent of making something “joyful, something for children” (so the artist himself).

The Tinguely Museum is also an active documentation center on the work of the artist and his contemporaries, and it is also a vibrant exhibition center that hosts annual exhibitions of modern and contemporary artists, mostly related to the themes of Tinguely’s poetics. It is, then, also an authority on the preservation and restoration of kinetic art: keeping Tinguely’s works alive requires complex conservation and preservation work, guaranteed each year by the museum’s experts. The museum’s website is a rich source of information and a starting point for organizing a visit: there you can find information about the works, exhibitions, and activities that the museum offers, as well as various insights into the figure of Tinguely.

|

| The engaging Tinguely Museum in Basel, the institution where Jean Tinguely's work lives on |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.