It is one of the most fascinating places in ancient Rome, though perhaps little known: we speak of the Crypta Balbi, an ancient urban complex that today constitutes one of the four sites of the National Roman Museum. It spreads across an area of one hectare in the very center of Rome, a few steps from Largo Argentina and is an extraordinary example of a museum of urban archaeology.

The complex, connected to Balbo’s theater, one of the three theaters of ancient Rome, can be reached from Via delle Botteghe Oscure. In this block of old Rome one can admire the processes of development from antiquity to the 20th century-a journey through time and history. An archaeological development spanning two thousand years. During these decades all the layers have been excavated through which all the stages of the city’s growth have been reconstructed. Visiting this place gives a clear understanding of the history of the urban transformation of the area and the capital, thanks to panels, drawings and plastic models. Since the 1980s it has finally been home, as anticipated, to one of the world’s first urban archaeology laboratories.

The Crypta is named after Lucius Cornelius Balbo, a politician and banker friend of the Emperor Augustus, who in this area in 13 B.C. with spoils of war built the theater whose traces are still visible today. Over the centuries the first Christian churches were then built including that of Santa Maria Domine Rose in the Middle Ages. Also dating back to this period are the first settlements of Via dei Delfini one of the streets that encloses the block and the artisans’ stores with their commercial activities, located in Via delle Botteghe Oscure, which owes its name precisely from those “dark” rooms because they were completely without windows.Instead, in the Renaissance the convent of St. Catherine was built while the church of St. Stanislaus and the Polish hospice date from the 18th century.

The Museum building, built on top of the ancient Roman building behind the Balbo Theater, is divided into two sections. The first section, Archaeology and History of an Urban Landscape, presents the results of archaeological excavations conducted since 1981 in the building complex. The second section, The City of Rome from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Archaeology and History is devoted to the life and transformations of the city between the 5th and 10th centuries.

The museum rooms are housed in the seventeenth-century dormitory of the monastery of Santa Caterina dei Funari, which was built on the houses of merchants who, in turn, had been built on the ruins of ancient monuments. Numerous artifacts are on display, mainly found in the excavations of the Crypta: coins, seals, ceramics, ivory. These are finds ranging from the Roman age to the 20th century. Also housed are some objects found in other areas of the city, but which, nonetheless add to the museum context, such as some frescoes from the church of St. Hadrian, which tell of the social changes and living conditions of the city of Rome and its inhabitants between the fifth and ninth centuries AD.

Museum areas of the Crypta

Museum areas of the Crypta Museum areas of the

Museum areas of the

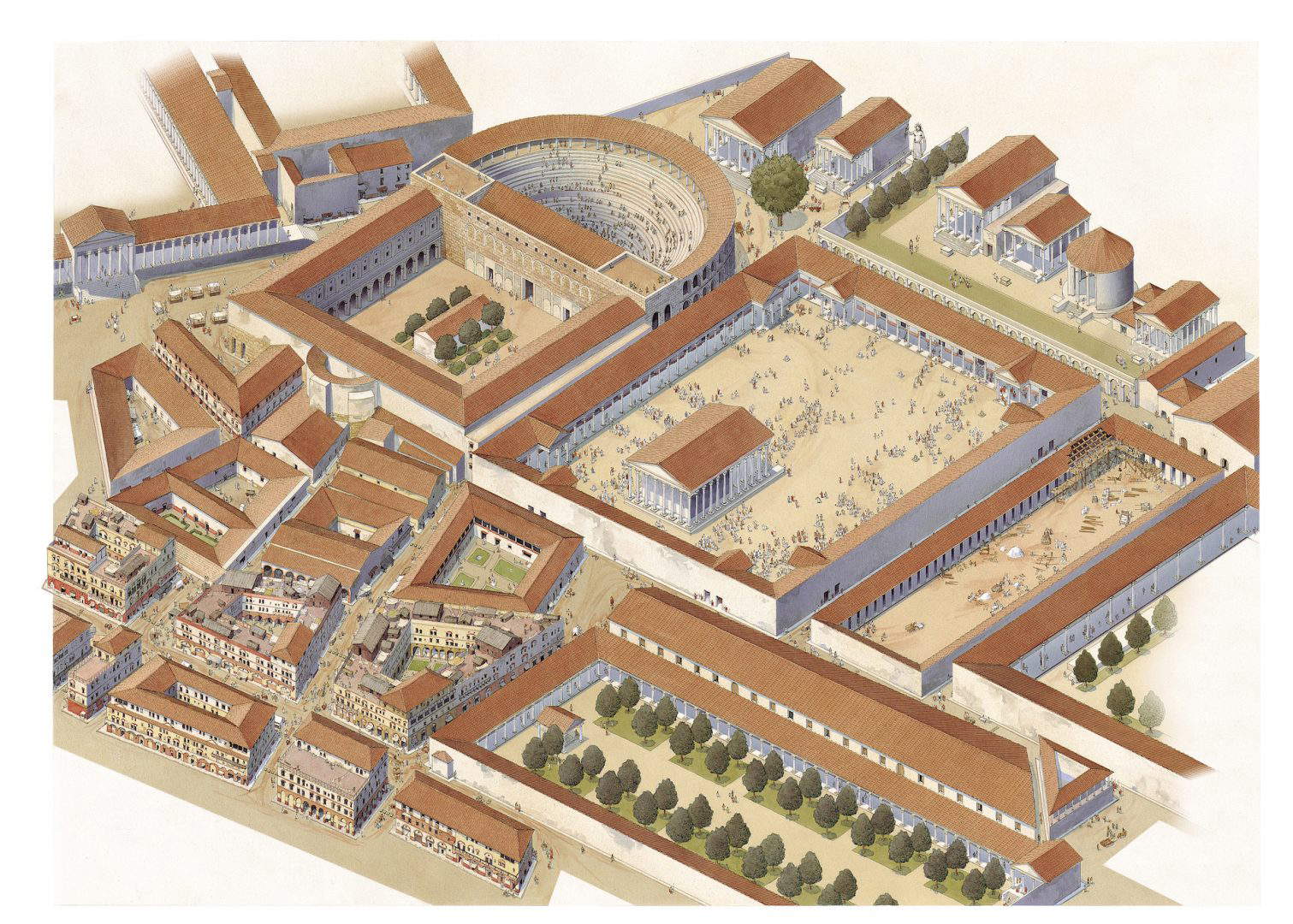

The museum contains the remains of the many productive activities that animated this area of the city for centuries: workshops that worked metals and glass, baked marble to make lime, cloth and rope manufacturers. Tools for some of the work and implements for the sewing business are on display here, as well as glass cruets and jewelry, which tell the story of life in the Rome of the Empire. The museum also traces, through other material, the phases of early medieval Rome, which in the crypta Balbi takes shape through artifacts, graphic reconstructions and models. In particular, the graphic of the Reconstruction of the imperial-era view of the area of Balbo’s theater, the Reconstruction of the 5th-century view, and that of the Reconstruction of the 10th-century and 14th-century view, through which it is possible to clearly witness the transformations of the place where the Museum and the adjoining archaeological area stand today.

The unique peculiarity of the Crypta Balbi are the external underground spaces, the exploration of which allows the visitor to confront antiquity, from the most monumental to the most popular. From the remains of the smallest of the three theaters of ancient Rome with a large square with an adjoining portico, called precisely “crypta” because of the scarcity of light that affected it, from where a wide exedra opened up where one can still walk today. It is located on the side opposite Balbo’s theater. The wide exedra, testifying to the existence of a significant dwelling, during the 6th century housed a series of burials and later, in the century just following, used as a dumping ground for materials produced by a nearby workshop.

In the 8th-9th centuries a limekiln was planted in the exedra, which was used to turn into lime valuable worked marble recovered from nearby Roman monuments and from the exedra itself. Marble fragments from the excavation are located inside the Museum. In the 11th century the exedra also housed a balneum, a facility for the personal care of monks, equipped with two heated rooms with a furnace for heating water: this is an important find on the Roman tradition of baths and body care that remained in use until the Middle Ages. The exedra, like many other spaces in the entire Roman monument, has suffered the ravages of abandonment and neglect over the years, but today, this large circular space, cleared of debris, offers a glimpse into the daily life of the time.

The same fate befell the theater. The large structure, which could hold up to more than seven thousand spectators and was embellished with luxurious decorations, demolished and then renovated, housed stores and artisan workshops in the Middle Ages. And then, as was the custom at the time, it was exploited for other constructions, or sourcing building materials for other artifacts. Finally, the theater was then the subject of filling with scraps of material and refuse, even burials whose remains are preserved and visible in the museum.

In the early Middle Ages documents and archaeological surveys attest that in the area of the arcade there was a convent and the church of Santa Maria Domine Rose named after a noblewoman remembered as its founder. The church was connected to the so-called Castellum Aureum, a fortified residence built on the ruins of the Theater. Only a few walls, restored several times, are preserved from the original construction. The surviving paintings can still be seen in the museum’s outer courtyard; they refer to the tombs of two benefactor bishops: Ludovico Torres and Bartolomeo Piperis. In 1536 Ignatius of Loyola, who had received the church from Pope Paul III, founded a home for poor girls there. It was again the Spanish monk who promoted the demolition of the church and subsequent rebuilding, which was done by Guidetto Guidetti, a pupil of Michelangelo. The church and convent were dedicated to St. Catherine of Alexandria to whom the funari, rope-makers who had meanwhile settled in the area, were devoted. This settlement gave its name to the Funari street where the church stands today called, precisely, Santa Maria dei Funari.

Through streets and workshops, one enters an ancient Roman quarter with a bakery, a laundry for removing stains and dyeing cloth(fullonica), several washing and soaking tubs still visible today in the outdoor area and the nearby drying rack, and a mithraeum (a place of worship dedicated to the god Mithras): basically the only place in Rome where one can still see or study what life in the city was like in the 1st or 2nd century.

To the 1st century AD dates the Porticus Minucia Frumentaria, a square portico located in the area today between Via delle Botteghe Oscure and Corso Vittorio Emanuele, north of the Crypta Balbi, once used for free grain distributions to the citizens of Rome. During the Middle Ages houses were built on Via dei Delfini, which owes its name to the Delfini family, a branch of the Dolfin family lineage of Venice, nobles who had moved to Rome in the 15th century. In this area the family built several richly decorated buildings over time. These include the house where St. Ignatius of Loyola lived between 1538 and 1541 where, on September 27, 1540, he received the bull "Regimini militantis Ecclesiae" by which Pope Paul III approved the Society of Jesus.

The present palace, which still preserves the room where the saint lived, has three floors. At its entrance an ashlar portal beside which, inserted in the facade, a column is still visible: almost certainly an artifact belonging to the portico of an earlier dwelling.

Finally, in the 18th century the complex was enriched by the church of St. Stanislaus, now the national church of the Poles living in Rome. Some documents reveal that the church of San Salvatore in pensilis de Sorraca stood here already in medieval times. It was then completely modified in 1580 by Polish Cardinal Stanislaus Osio when it was granted to him by Pope Gregory XIII. The cardinal dedicated it to St. Stanislaus Szczepanowski, patron saint of Poland. In the 18th century the church underwent new interventions directed by Ignazio Brocchi, architect of the King of Poland Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, which gave it the appearance it still presents today.

A visit to the Crypta Balbi, then, is more than a visit to a museum: it is a journey, meanwhile, into the everyday life of ancient Rome, and it is also a journey through the history of the city. One moves through time and space. For fans of the history of ancient Rome, therefore, it is an essential stop, a place to visit and to return to.

|

| The Crypta Balbi, a journey into the everyday life of ancient Rome |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.