Prato, Intesa Sanpaolo opens Palazzo Alberti: you can see the treasures of CariPrato

Starting March 25, Intesa Sanpaolo opens in Prato the Gallery of Palazzo degli Alberti, which the group strongly desired to allow the public to view an important nucleus of 90 works from the collection that once belonged to Cassa di Risparmio di Prato, now owned by Banca Popolare di Vicenza S.p.A. in L.C.A. The initiative, carried out by the Bank’s Culture Project, is part of the Group’s ESG activities aimed at contributing to the cultural growth of the country and the economic and social development of the territories.

After nearly three years of renovation work on the area of the Palazzo degli Alberti reserved for the Gallery, completed despite the pandemic, Intesa Sanpaolo is thus fulfilling the commitment made in 2018 to offer hospitality and protection to the prestigious nucleus of works of art, including paintings and sculptures, that are part of the cultural and artistic heritage linked to Prato and its history. The construction site for the adaptation of the building to an exhibition venue has seen the opening of a dedicated access, the compartmentalization, air conditioning and securitization of the rooms intended for museum use, as well as the creation of a storage room for works of art not on display. Thanks to the dialogue with Banca Popolare di Vicenza S.p.A. in L.C.A., the Municipality of Prato and the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the Metropolitan City of Florence and the Provinces of Pistoia and Prato, it was possible to allow the reopening to benefit the community, in line with the principles of Intesa Sanpaolo’s Progetto Cultura. Central was the objective of protecting the artistic heritage: in addition to the architectural project - in agreement with Banca Popolare di Vicenza S.p.A. in L.C.A. and the Superintendent’s Office - important conservation work was carried out on the works.

The Gallery of Palazzo degli Alberti inaugurates with a layout that is in continuity with the previous one with larger and more functional spaces for the visitor route. The collection consists of 142 works, 90 on display and the remainder on deposit, including particularly valuable assets such as masterpieces by Giovanni Bellini, Filippo Lippi, the celebrated Coronation of Thorns attributed to Caravaggio as well as works by Puccio di Simone, Bronzino, Santi di Tito, Poppi, numerous prestigious works of seventeenth-century Florentine art, and a substantial number of sculptures by Lorenzo Bartolini, an artist from Prato active in the first half of the nineteenth century. Admission is free for all visitors with opening hours on Saturdays and Sundays, 10:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. (last admission one hour before). Ticket reservations for the accompanied tour are recommended by logging on to www.gallerieditalia.com or emailing galleriaprato@civita.art.

The exhibition route

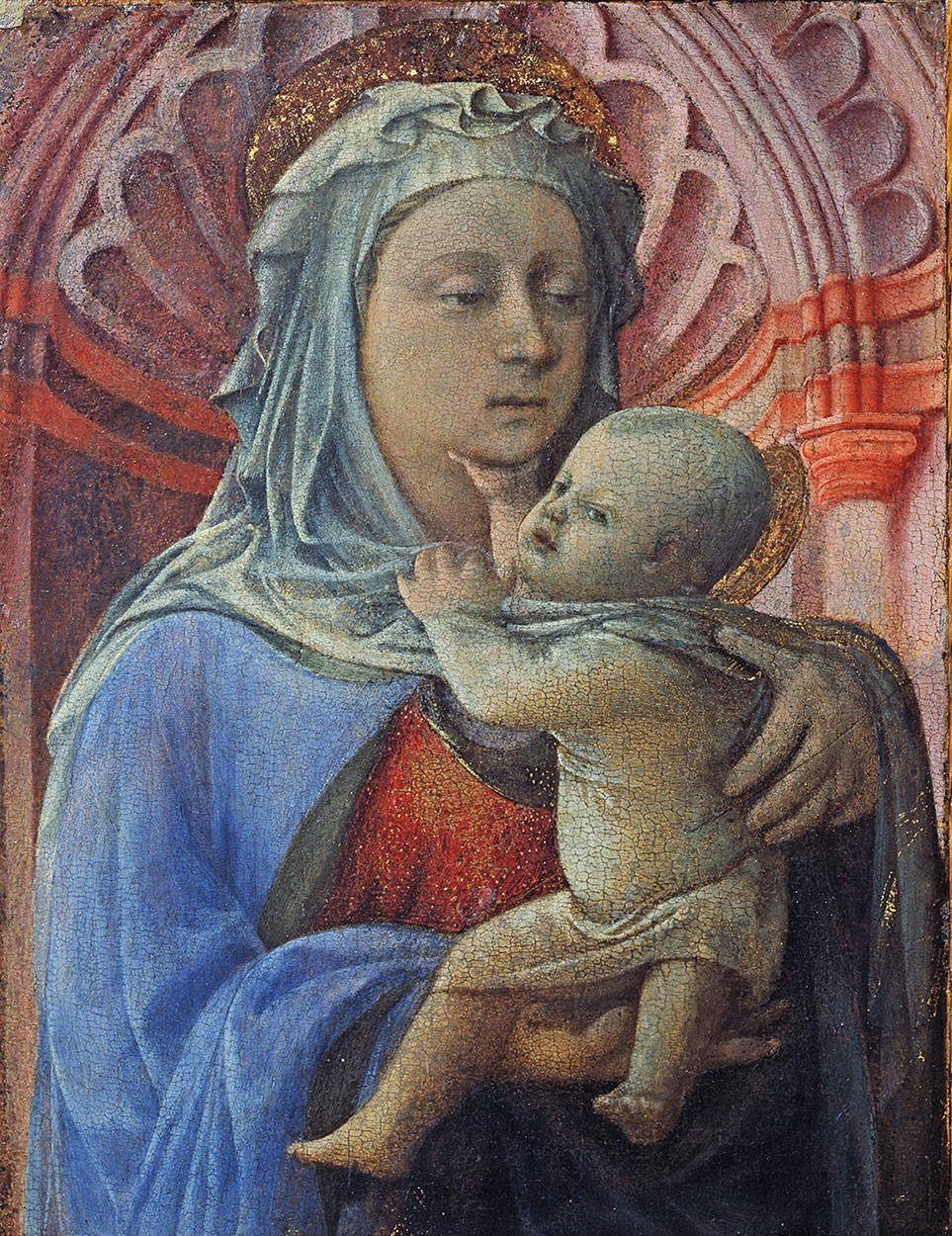

The exhibition itinerary, curated by Lia Brunori, a functionary of the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio for Florence, Pistoia and Prato, opens with two frescoed tabernacles from the early 15th century that focus on the relationship with the city and its patron saints, and then arrives at the work of Filippo Lippi, who embodies the artistic culmination of a pictorial production that already showed episodes of relevance in the territory since the Middle Ages. Lippi’s small panel is exhibited, which, a probable fragment of a slightly larger composition intended for private devotion, already contains, around the mid-1530s, the lines of development at the basis of his art. Despite the small proportions, the monumentality of the absorbed Madonna denounces the lesson of Masaccio, as does the robust figure of the little Jesus, whose vigorous and affective gestures recall the achievements of Donatello, while the architectural framing evokes Brunelleschian spatiality.

The Gallery continues following chronological order, highlighting specific artistic manifestations from time to time. It continues with Bellini’s masterpiece, Christ Crucified in a Jewish Cemetery: the painting, an absolute masterpiece and the pinnacle of Giovanni Bellini’s stylistic journey, was preserved as early as the 17th century in the Niccolini da Camugliano palace in Florence, recalling the importance of the circulation in Tuscany of masterpieces of Venetian painting that influenced local artistic culture. Agreed to be attributed to Giovanni Bellini, critics are divided, however, on its dating, which ranges from the years 1480-1485, in keeping with the panel of St. Francis in the Frick Collection in New York, to 1501-1502, by virtue of the disputed dating reported on one of the Jewish tombstones and in stylistic assonance with the coeval Transfiguration in Naples. Because of its setting, the work constitutes an iconographic unicum; according to a narrative punctually taken from the Gospels, the cross is placed inside the Jewish cemetery, totally occupying the center of the composition, which is articulated on at least three distinct planes, incorporating a northern setting that Bellini enriches with new and original elements. The second floor presents a series of tombstones with Hebrew inscriptions arranged in a barren, rocky garden that, on the other hand, beyond the cross, unfolds in the forms of a richly vegetated meadow, evoking the flourishing of life through Christ’s sacrifice. The rendering of the numerous botanical species, all of which can be identified and traced back to a complex symbolic system, is precise and careful. On the second floor are a group of houses, a stream that feeds a mill, and a road that unravels from the second floor to the bottom floor where the town perches. A composite city, at once real and ideal, in which some buildings identified in the cathedral and tower of Piazza di Vicenza, the bell tower of Santa Fosca in Venice and the cathedral of Ancona stand out.

Further focuses are edicated to the sixteenth-century painting tradition and the age of the Counter-Reformation before arriving at Caravaggio with theCoronation of Thorns made known by Roberto Longhi as an ancient copy from a Caravaggio composition. The canvas underwent a restoration in 1974 that freed it from extensive repainting and made it recover the legibility of its high artistic qualities, so that part of the critics traced it back to the direct hand of the great painter, as the diagnostic campaign conducted in 2001 by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure would seem to have further confirmed. Painted in Rome after commissions in San Luigi dei Francesi (1599-1600) and Santa Maria del Popolo (1600-1601), and in close proximity to the Vatican Deposition (1602-1604), it is probably to be identified with the work of similar subject matter that the painter documented having executed by 1605 for the nobleman Massimo Massimi and of which a replica is preserved in Genoa in the church of San Bartolomeo della Certosa di Rivarolo. The link with the Roman nobility, educated and linked to the pauperistic spirituality of St. Philip Neri, underlies not only this work but all of Caravaggio’s contemporary production, which found in the Del Monte, Massimi and Giustiniani patrons sensitive to the poetics of reality and the last. It was precisely in the Giustiniani’s collection, which counted some 15 of his works, that we also count the Coronation with Thorns now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, which, although more complex in its setting, shows the same artistic and spiritual temperament that made this painter, both brilliant and cursed, so much disliked in academic circles.

One section is devoted to the seventeenth century between the sacred and the profane: important indeed is the nucleus of seventeenth-century works that, moving from Caravaggio’sCoronation of Thorns, unravels a narrative in images of the many facets that painting, predominantly Florentine, took on in the seventeenth century. The far-sighted selection of works made in the 1970s and 1980s by Giuseppe Marchini, a profound connoisseur of seventeenth-century art and Prato’s culture, makes it possible to appreciate exquisitely crafted works by the leading artists of the period, appreciate their connections and differences, discover paths and recognize models. Through a play of cross-references and suggestions, we will discover at a glance the impetuous naturalness of Anastagio Fontebuoni in dialogue with Caravaggio, to whom Bartolomeo Salvestrini’s work also looks, and then the crystalline and intense truth of Lorenzo Lippi, the sumptuous history painting of Matteo Rosselli, the refinement of Giovanni Bilivert, the warm and nuanced color of Jacopo Vignali, and the classical inspiration of Cesare Dandini. And again the sensual sweetness of Francesco Furini, the mirrored spirituality of Carlo Dolci, the noble portraiture of Suttermans, the eccentric experiences of Rosi or Mehus, and the very high quality of all the works, as evidenced by Martinelli’s extraordinary Magdalene. Sacred but above all profane works, an incredible sampler of subjects and literary sources, all works to be enjoyed in their individual values, without pretending to identify historical paths, since the Florentine environment of the seventeenth century, which was of constant reference for the suburbs and in particular for Prato, which in churches, palaces and museums numbers works by these same artists, as Marchini recalls, “did not create his own coherent and uniform language in the strict sense of a school, but with extreme individualism gave himself to disparate experiences, eclectically open to external contributions favored by the personalistic policy of the Medici princes who invited at all times passing artists and were participants in the various directions of the culture of the time.”

The conclusion is entrusted to the nucleus of works by the great Lorenzo Bartolini: a central figure in the panorama of 19th-century sculpture, Lorenzo Bartolini became a role model of his time for the innovative balance of naturalness, formal perfection and expression of moral values that he lavished in his works. Born in the province of Prato, in Savignano in Val di Bisenzio on Jan. 7, 1777, to a modest family, he soon moved to Florence, and although his biographical and artistic story was conducted outside Prato, the city has cultivated the memory of the important fellow citizen over time. In fact, alongside the nucleus of works exhibited in the Museum of Palazzo Pretorio, the present relevant collection testifies with works of undoubted quality, the salient stages of Bartolini’s production in his city of origin. The busts of Elisa Baciocchi and Maria Luisa of Austria, respectively sister and wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, recall the artist’s prolific activity upon his return from Paris, at the time of his direction of the sculpture school of the Carrara Academy and of the so-called Elysian Bank (1807-1814), deputed to the creation of portraits of the Napoleonites, of whom Bartolini was a fervent supporter. To the same cultural climate also belongs the bust of Paris, which, as a copy from Canova, testifies to the artistic dialogue with the great master of Possagno. Returning to Florence in 1814, despite the aversion of academic circles, Bartolini led a prestigious workshop frequented by aristocratic patrons of international stature and produced intense and fascinating sculptures, of which Trust in God is an exemplary example. A smaller-format replica of the celebrated commission of Rosina Trivulzio Poldi Pezzoli, the work, along with the marble with the Scorpion Nymph, also a reduced version of the important sculpture now in the Louvre, provides insight into the methods of making Bartolini’s works, which, while responding to the demands of the art market, keep their quality intact. The Model of the monument to Leopold II of Lorraine, which was never made, alternates between the public celebratory themes and the moral and domestic ones with which Bartolini’s career (he died on January 20, 1850) ends, leaving in the large sculptural group of Maria Maddalena Pallavicini Barbi Senarega depicted in the act of protecting her daughter from the bite of a squirrel, his last unfinished work dedicated to The Maternal Fear, visible in the entrance hall of the Gallery.

The statements

“Intesa Sanpaolo,” says Michele Coppola, Executive Director Art, Culture and Historical Assets Intesa Sanpaolo, “is pleased to have contributed to the reopening of the Gallery of Palazzo degli Alberti, an important result achieved thanks to the work constantly shared with Banca Popolare di Vicenza S.p.A. in L.C.A., the competent Superintendency and the Municipality of Prato, in a climate of strong synergy between public institutions and private realities. Coming out of the difficulties imposed by the pandemic, it is a pleasure to return to experience the beauty of a precious collection that intimately belongs to the identity and history of this city, further confirming the Bank’s attention to the enhancement of the cultural heritage of the territories of reference, in full consistency with the commitment of our Culture Project.”

“It is with particular pride that today we are offering Prato and those who visit it the opportunity to access a new exhibition environment rich in works, masterpieces and an important part of the history of this city,” stresses Luca Severini, Intesa Sanpaolo Regional Director for Tuscany and Umbria. “A cultural heritage that as Intesa Sanpaolo we are particularly pleased to have been able to enhance, fulfilling the commitment made in 2018 with meticulous attention to identity, care and protection of heritage, and the specificities that this territory expresses.”

“The new, invaluable display in the Gallery of Palazzo degli Alberti,” comments Matteo Biffoni, mayor of Prato, “makes us understand the inseparable link between the works and the city. Masterpieces that tell a story of art and emotions: to be able to return them to the citizens is a joy and a satisfaction, made possible thanks to the willingness of Intesa Sanpaolo and thanks to the fundamental collaboration of the Superintendence and the Municipality of Prato and also thanks to those who, like the Friends of the Museums, firmly believed in this bond.”

“Thanks to the commitment of Intesa Sanpaolo and the willingness of Banca Popolare di Vicenza in L.C.A., which has made available the works it owns,” adds Andrea Pessina, Soprintendente Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the metropolitan city of Florence and the provinces of Pistoia and Prato, “the possibility of admiring a very important collection is returned to the community of this area. I believe that the symbolic significance of today’s event is extremely relevant: this inauguration strongly emphasizes the public function reserved for cultural heritage, in implementation of what is enshrined in Article 9 of the Constitution, and this is a goal that has been achieved thanks to the collaboration put in place between the institutions and the sensitivity of Intesa Sanpaolo.”

|

| Prato, Intesa Sanpaolo opens Palazzo Alberti: you can see the treasures of CariPrato |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.