Revision underway for the captions and cards of works at the Prado Museum in Madrid. It is actually a path that the Spanish museum has been on for some time but which is being discussed again after Congress, or the counterpart of our Chamber of Deputies, approved last January 18 (with 312 votes in favor and 32 against by Vox deputies) a constitutional reform that calls for the amendment ofArticle 49 of Spain’s Constitution, where it says that public authorities shall carry out a policy of prevention, care, rehabilitation and integration “for the physical, sensory and mental handicapped, offering them the necessary specialized assistance.” The reform eliminates the term “minorities” ( disminuidos in Spanish) replacing it with “persons with disabilities”(personas con discapacidad). Congress will now send the text to the Senate where it must receive final approval.

The Prado took the opportunity to inform its visitors of the project to “update” captions and cards, which in light of what the Spanish Parliament is passing becomes an even more urgent issue according to the institute. “What we do,” Ana Martín of the museum’s Documentation and Archive Service said in a video released by the Prado (on its Facebook and Instagram pages), “is to be aware of the reality of the museum and to be aware of everything that happens outside the museum. Now it is a topical issue: political consensus has been reached to change in our Constitution the term handicapped for people who have disabilities. This measure seemed interesting enough for us to think about how we are thinking about our audience all the paintings, all the artworks where people with disabilities are depicted. It’s work that we didn’t start now, that we were already doing, that led us to consider that there are descriptions with terms that now sound offensive.”

What does this mean? Pejorative terms of physical defects such as dwarf, handicapped and the like that are considered offensive will be replaced. The process has been underway for some time: at the end of 2022, for example, expressions such as “wife of” referring to women had been removed from the captions for some works (an issue, the latter, that the Prado had addressed during a tour entitled El Prado en femenino organized in collaboration with the Ministry of Equal Opportunities, when the information was removed from some captions): the idea is that emphasizing that a woman is someone’s wife does not help the visitor focus on what the woman in question did in her life, for example, the political role of certain queens or princesses, which would risk being overshadowed.

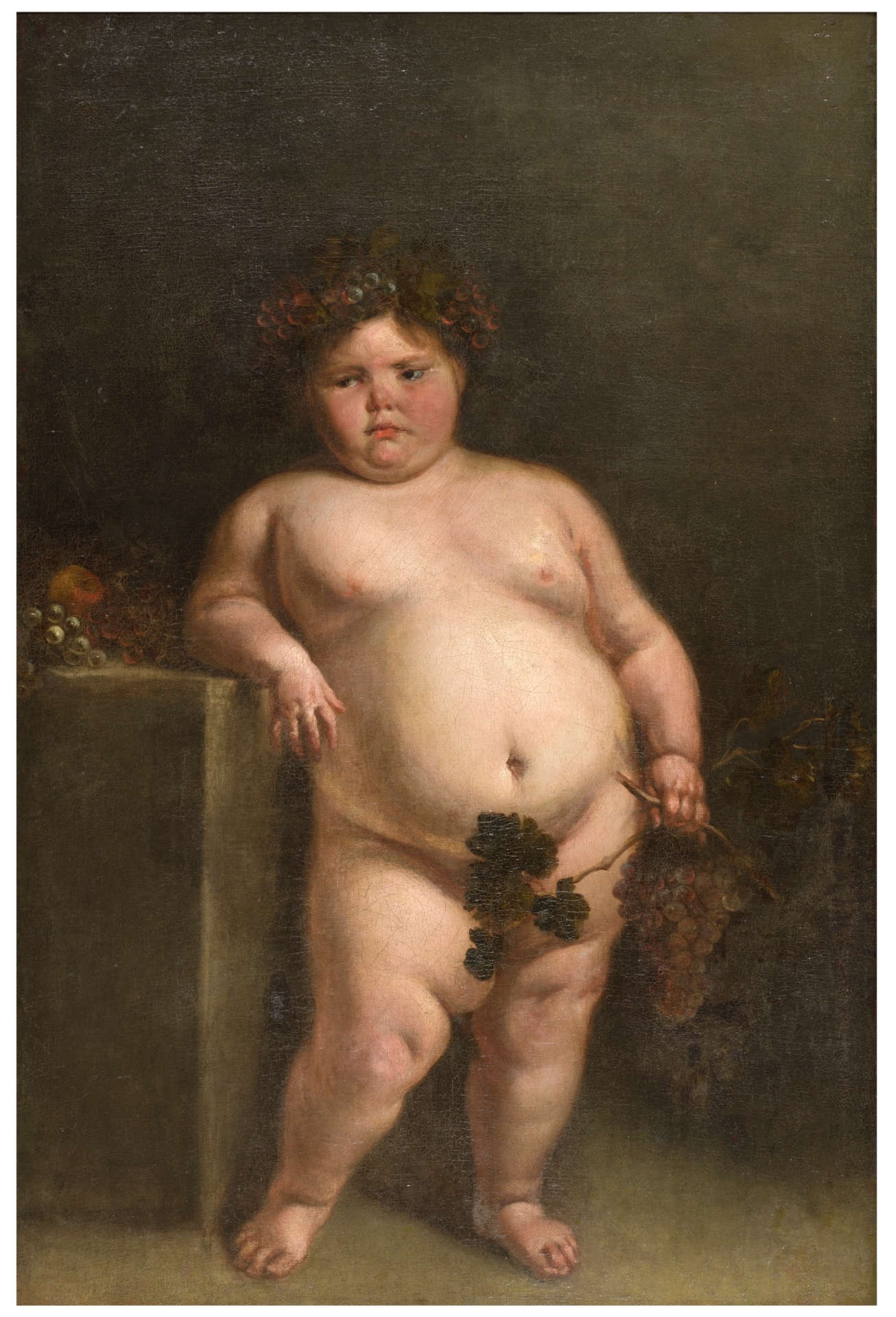

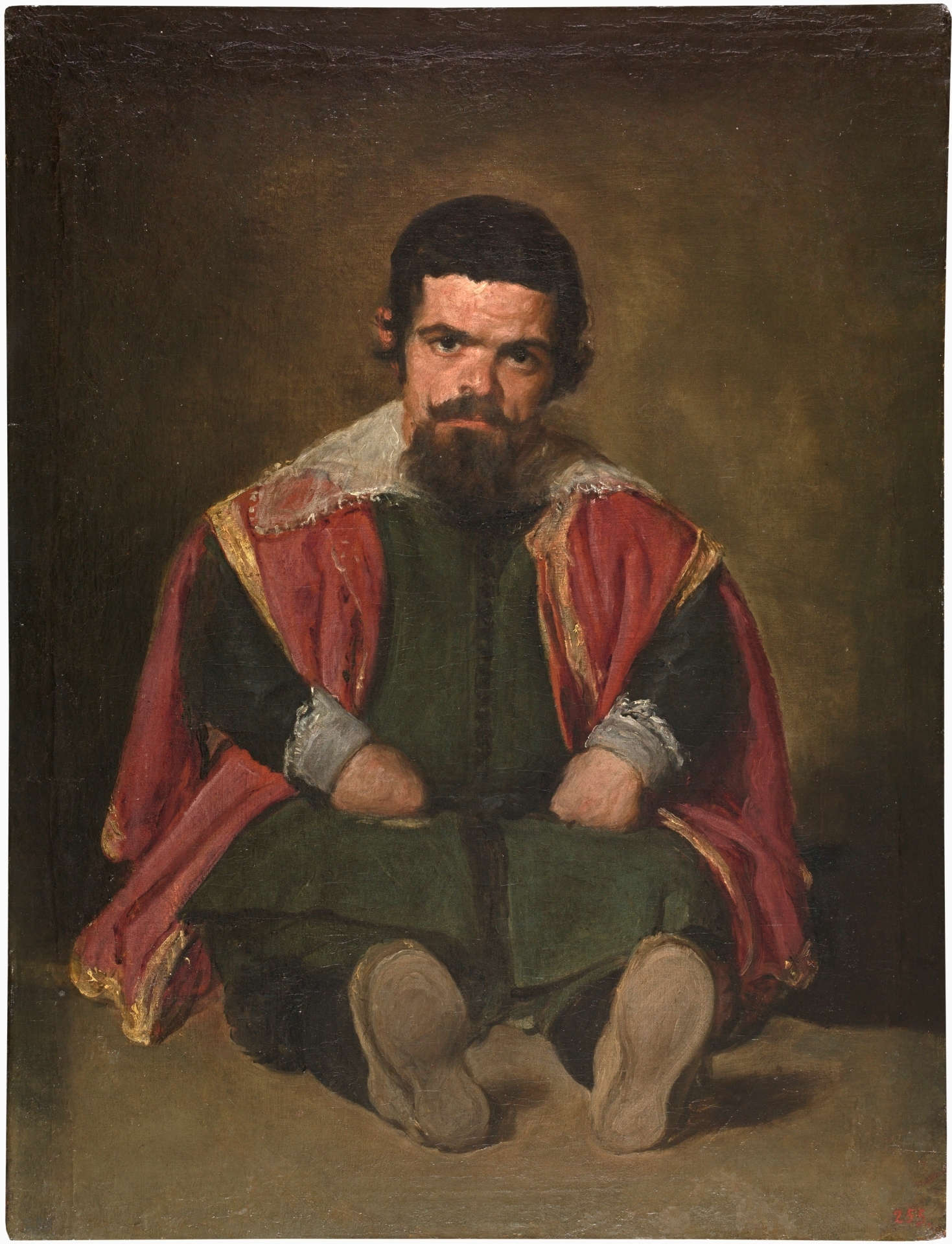

“The sensibility of writing is not the same as it is today,” Martín continued. “What we did is to look for words that seemed a little shocking and to eliminate them when they added nothing to the description of the work, or to look for a word to replace it.” The greatest difficulty, Martín explained, is when words that sound offensive today are found in titles of works that have a long history or tradition. In this case, the picture was given the name of the character depicted or, in case the name is unknown, the characters were identified with their occupation (for example, instead of “dwarf” it was thought to use “court jester” since these characters were almost always employed in this activity, and the word “dwarfism” was changed to the more correct “achondroplasia”). Perhaps the most telling example is the pair of 1680 paintings by Juan Carreño de Miranda (Avilés, 1614 - Madrid, 1685) depicting girl who was part of the court of Charles II, Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, who due to her unattractive appearance was called La monstrua (“the monster,” also feminine in Spanish), and the two paintings have always been called La monstrua vestida and La monstrua desnuda (so already in seventeenth-century inventories: “Dos Retratos de la Monstrua” is in fact mentioned in that of 1686). Now the museum simply calls them Eugenia Martínez Vallejo vestida and Eugenia Martínez Vallejo desnuda. Or just think of the many portraits of court jesters executed by Diego Velázquez (Seville, 1599 - Madrid, 1660), such as El Niño de Vallecas, El bufón El Primo (which has always been historically known as Retrato de enano), or even the Portrait of Prince Philip and Miguel Soplillo by Rodrigo de Villandrando (Madrid? 1588 - Madrid, 1622), which is also recorded in the inventories as “A prince with his hand over a dwarf.” Instead, it was decided to leave the title, even if it is offensive, if it was given by the author, as in the case of the engraving El maricón de la tía Gila (“Aunt Gila’s Faggot”) by Francisco Goya (Fuendetodos, 1746 - Bordeaux, 1828), since it is a title given by the artist and written in his own hand on the sheet.

At present, the museum has already analyzed some 27,000 sheets on the site and about 1,800 captions of the paintings on display. Some have already been changed (and a long time ago, too: the two portraits by Eugenia Martínez Vallejo have in fact had the new title for years, at least on the website, where the first attestations of the non-offensive title date back to 2018), others will be soon. In any case, the Prado lets us know, the old titles have not been eliminated: they have been left in the database as “historical titles,” in the notes on inventories so that, for example, a scholar, enthusiast, or visitor who searches the Prado’s database for a work with its old title, the result will still come out highlighting, however, that the title sought is no longer the one with which the museum presents the work.

“What we have done ultimately,” Martín concludes, “is to seek a balance between historical information and the preservation and transmission of the message and explanation of the artwork in accordance with current sensibilities. It is a process that continues, that we have not finished and that we will continue to work on, because really what we are interested in is that we understand why certain works were made.”

|

| Prado updates captions: away with terms like "dwarf," "handicapped," and others |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.