Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria reopens with new layout and many new features

Reopening after a year of work, and with new layouts and spaces, the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia, one of Italy’s most important museums. Appointment for the public on July 1 to admire the new route designed to take visitors to discover the masterpieces of the gallery, the institution that, moreover, preserves the largest number of works in the world by Perugino. The new route has been designed under the banner of tradition and innovation: the National Gallery of Umbria is being rethought with a light, modern, cutting-edge, cue-rich layout, with a renewed arrangement of the works, interesting multimedia apparatus, interdisciplinary and research-oriented approach. The interventions, costing 5 million euros, bear the signature of architects Daria Ripa di Meana and Bruno Salvatici and were financed by the Development and Cohesion Fund.

The National Gallery of Umbria houses mainly paintings of sacred subjects dating from the 13th to the 18th century, and for this reason the layout follows a strictly chronological iter, although with important innovations compared to the past (see in the dedicated section). In addition, in the new layout the applied arts (goldsmithing, medals, ivories, textiles) are placed in dialogue with painting and sculpture, to represent the evolution of figurative languages and the interaction between different techniques through the centuries.

The new displays are also environmentally conscious. The high-tech lighting system is equipped with presence detectors that allow the light intensity to be automatically calibrated; in the absence of visitors, the lights are dimmed to a minimum, thus allowing significant energy savings. There are also novelties from an editorial point of view: on the occasion of the refitting, Silvana Editoriale has produced a new art historical guide edited by director Marco Pierini, with an essay on Palazzo dei Priori and the history of the Gallery by Marina Bon Valsassina. Gnu and Franco Cosimo Panini Editore have produced a children’s guide starring Pimpa: the little red-dotted dog drawn by Altan will accompany the youngest children on their visit to the Perugian museum, who, along the way, will discover many curiosities about the masterpieces and will be involved in fun activities to do during their stay at the museum or on their return home, as a reinforcement of the content they have learned. The book has no shortage of gimmicks for play: stickers, templates to peel off, and a comic strip story about Perugino.

The Gallery’s official website(www.gallerianazionaledellumbria.it) has also had a redesign and functions as a container and tool for in-person visits, then also as a web app. The site, which is more intuitive, dynamic and versatile than its predecessor, has been developed to be accessible, with audio tracks of the descriptions of the works in the exhibition itinerary (in Italian and English), videos in LIS, multimedia and in-depth content, thematic paths, such as the musical one, and much more. Finally, the new pages dedicated to the collection offer the extraordinary possibility of penetrating into the depths of the surface and perceiving every single detail of the works thanks to gigapixel scans created as part of a vast collaborative project with Haltadefinizione that reconciles the needs of fruition with those of conservation. The new site is flanked by the Digital Gallery project, systematization of some 100,000 freely accessible documents that allow users to peruse the historical archive, the restoration archive and the large amount of photographic material.

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery ofWhat’s new in the layout

Among the first novelties are some inserts of works recently acquired or recalled from storage. These include Giovanni Baronzio’sImago Pietatis (circa 1330), Melozzo da Forlì’s Salvator Mundi (1476-1485), the Presentation of Jesus to the Temple by Giovambattista Naldini (1535-1591), purchased in 2018, a sketch of the work in the Gallery, the Madonna and Child with St. Gertrude by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747), and St. Anne, St. Joachim and the Infant Mary by Francesco Mancini (1679-1758).

Monographic rooms have also been created to recount the careers of the major artists in the collection. The ones with the greatest impact are the two dedicated to the most important Umbrian master, Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci, known as Perugino (who thus rises to be the great protagonist of the new arrangement), one on the third floor for the works of his youth and early maturity, the other, on the lower floor, for his late production, with the most significant evidence of his last twenty years of activity, in a highly evocative arrangement that gathers masterpieces first distributed in seven different rooms. What’s more, in 2023, on the occasion of the fifth centenary of his death, Perugino will be celebrated through a series of research, educational, editorial and exhibition activities, as well as through the organization of cultural events, which will have its focus precisely at the National Gallery of Umbria.

Compared to the past, the new Gallery also presents a drier selection of the collection, identified with expedients that have led to represent, in depth, the breadth and richness of the collection, while making the visit more fluid and enjoyable. The creation of an Exhibition box for small temporary exhibitions will allow the works in storage to be appropriately enhanced through specific events.Also among the novelties are the innovative bases under some important works on wood, an original solution conceived by the staff of the National Gallery of Umbria and developed by the company Arguzia of Benevento: these are bases equipped with doors that can be opened wide and allow, thanks to an attached mechanical arm, the work to be moved forward, in total safety given also the presence of shock absorbers that eliminate stress and aluminum panels on the back of the works to avoid shocks. On the one hand, this technology saves on handling costs, and on the other hand, the works suffer less, as they are no longer fixed only to the walls and unload their weight onto the base.

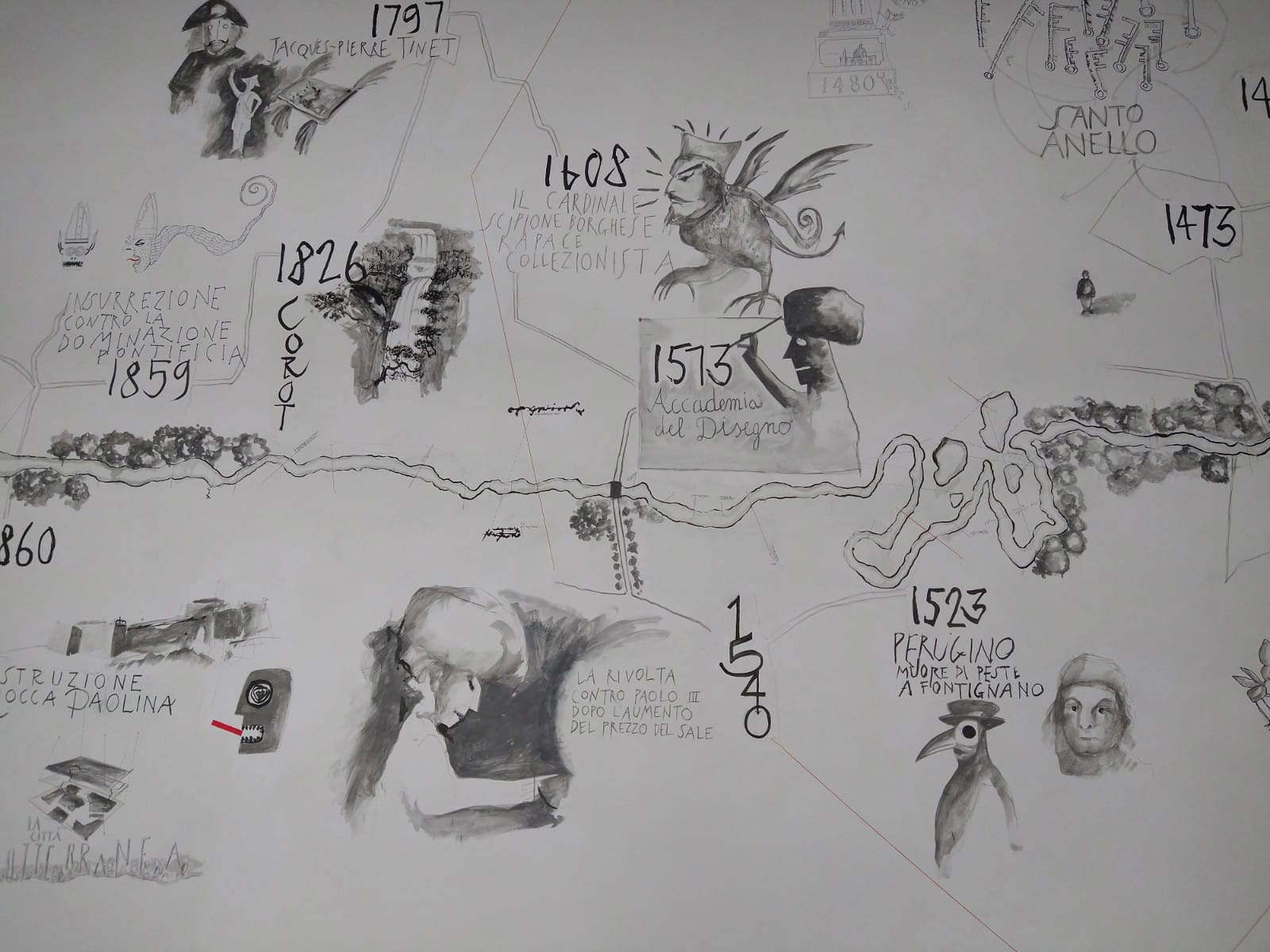

Again, for the first time, the National Gallery of Umbria is opening up tocontemporary art. On the back wall of the Cappella dei Priori, Vittorio Corsini has reinterpreted, using the same technique as then, the destroyed stained-glass windows and shaped in the wooden altar the new sacred centerpiece of the Palazzo dei Priori. Room 20 hosts the intervention that Roberto Paci Dalò made in watercolor graphite and Indian ink Ductus. These are images and words that reconsider some watersheds of history and art in Umbria, offering the visitor suggestions, elements of reflection, and formal remodulations capable of activating direct and intuitive mechanisms of knowledge. In addition, the new layout of the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria dedicates Room 39 to artists from Umbria or who have long worked in the region such as Gerardo Dottori, Alberto Burri, Piero Dorazio, and Adalberto Mecarelli who, with their presence and cultural depth, have participated as protagonists in the debate on contemporary art in Italy, influencing it profoundly.Among the works that the public can see are Gerardo Dottori’s Lunar Sunset, a lyrical Futurist landscape dated 1930, and Alberto Burri’s Black and White C2 from 1971, belonging like Dottori’s work to the museum’s collection, plus a tar by the same master from tifernate(Nero) and with a canvas by the Roman Piero Dorazio(Andi(i)Rivieni, 1970), both arrived from private collections on loan for use. Completing the room is a work made at the beginning of the third millennium in India, Bissau Hotel à Jaipur, by Adalberto Mecarelli from Terni.

To complement the visit, the multimedia project developed and implemented by Magister Art provides insights and unprecedented angles on a selection of the heritage on display. Among the interventions is an innovative multimedia apparatus, for which the definition of animated captions was coined: a nonphysical space where the missing pieces of some of the works now dismembered and scattered around the world are brought together in a non-didactic cognitive journey that breaks down physical and geographic boundaries. Some novelties can already be encountered in the atrium of Palazzo dei Priori with the bookshop expanded in size as well as in services, and with lighting that enhances its architecture, vaults, ribs and ogive windows, all unmistakable evidence of the building’s medieval origin.

The work has enabled the creation of a restoration laboratory and a fully accessible classroom, equipped with furniture and materials and instrumentation, including electronic equipment, to allow initiatives such as workshops, augmented reality activities and more to take place. In addition, one of the most significant novelties is the opening of an Art History library, rich in almost 30,000 volumes, set up in the Hall of the Gryphon and the Lion, which was made possible thanks to the concession by the Municipality of Perugia of this prestigious space, from now on available to students and scholars.

The

The

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The statements

“Today is a special day for Perugia, for Umbria, for Italy,” says Professor Massimo Osanna, director general of Museums. “After a year of work, a place of excellence, guardian of the national artistic and cultural heritage, is once again accessible to the public. A tradition that had one of its absolute summits in Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci known as Perugino, whose fifth centenary of his death will be remembered in 2023; an anniversary that sees the Ministry of Culture in the role of promoter of initiatives dedicated to him.”

“The reopening of the National Gallery of Umbria,” says Andrea Romizi, mayor of Perugia, “an integral part of our Palazzo dei Priori, is a source of great satisfaction and pride for the return to the city of a treasure chest of works of art that is among the most precious in Italy. The renovation, starting with the new layout, recalled a Renaissance building site, affecting various areas of the municipal palace such as the former Hall of the Gryphon and the Lion, which will house the Gallery’s library. As of today, the cultural offerings of the city and the region are restarting with significant momentum for an increasingly aware tourism in search of significant cultural deposits and complexes. Credit goes to the Ministry of Culture, which has allocated substantial funding, but above all to Director Pierini for his determination to return Palazzo dei Priori to us in its original form, and a Gallery made on par with the greatest international museums.”

“Rethinking the museum all over again,” explains Marco Pierini, director of the National Gallery of Umbria, “has meant, first and foremost, knowing how to keep a steady gaze on history and tradition, in order to grow, develop, and improve knowing well ’who we are’ and ’what we want to become.’ The bet we wanted to take was to transform an accessible museum into a welcoming museum. Firstly, for the works, for whose preservation and enjoyment special care has been taken; secondly, for the visitor who can walk through the halls choosing to enjoy the view of the works, to deepen his or her knowledge through the textual or digital apparatuses, or to rest legs and eyes admiring from the windows the city from whose monuments most of the artistic evidence comes.”

The new arrangements of

The new arrangements of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery of The new arrangements of the National Gallery of

The new arrangements of the National Gallery ofThe new exhibition itinerary explained in detail

The itinerary begins with a vision of very strong impact in Room I, The Art of the Thirteenth Century in Umbria. The visitor is in fact immediately in the presence of the large painted cross by the Master of St. Francis. The reading of the work will be aided by a video in which philological rigor and visual impact are combined: the first step of a rich multimedia path, which significantly enriches the experience of fruition for all types of audiences. The room brings together numerous paintings, sculptures and goldsmithing that tell the story of 13th-century Umbria. A land ignited by penitential movements and the spirituality of Francis and Clare of Assisi, where art responds to the needs of faith and is the protagonist of processions and sacred representations.

Then we move on to Room 2, The Fountains of Perugia, which houses the elements of the Fontana Maggiore by Nicola and Giovanni Pisano that have been musealized for conservation reasons and the surviving fragments of Arnolfo di Cambio’s “Fountain of the Thirsty.” Marbles and bronzes are illuminated by natural light, which enhances their material characteristics and plays of volume. From here one passes into the Cappella dei Priori rethought, as mentioned above, by Vittorio Corsini, who has reinterpreted in a contemporary key the destroyed stained-glass windows, made to a design by Benedetto Bonfigli, and has shaped in the wooden altar (designed taking Giotto’s mountains as a model) the new sacred fulcrum of Palazzo dei Priori. Room 4, Duccio di Boninsegna and His Legacy in Perugia, reconstructs the physical space of the primitive Priori Chapel, erected in the 14th century, giving new meaning to the material evidence that remains, thanks in part to the presence on the walls of Duccio di Boninsegna’s splendid Madonna and Child.

The works exhibited in Room 5, The Early Fourteenth Century, Between Florentine and Sienese Suggestions, document the primacy of the poles of Florence and Siena, with works representing all techniques: paintings by Giotto’s followers such as Marino di Elemosina and Puccio Capanna, stone and wood sculptures by the Sienese (perhaps Sienese?) Master of the Madonna of St. Augustine, and goldsmithing attesting to Siena’s absolute supremacy in this production. Room 6(The tower of Benvenuto di Cola dei Servitori: the domestic dimension) houses works from the first half of the 14th century related to private and devotional use. In particular, ivory objects of use from French manufactures of the first half of the 14th century. The tiny tabernacle, mirror box valance and medallion decorated with courtly scenes hark back to private rooms, precious gifts at weddings or engagements, whispered prayers in intimate and cozy spaces. Continuing, Room 7(The Mature Fourteenth Century between Umbria and Siena) hosts a survey of fourteenth-century art in Umbria, when the worksites of the Basilica of San Francesco and the Cathedral of Orvieto were confirmed as hubs of innovation in the figurative field. Finding its place in this space is Taddeo di Bartolo’s polyptych of San Francesco al Prato, which will be reconstructed on two sides as it was originally placed on the high altar of the Perugian church. Room 8(Gentile da Fabriano and the Late Gothic in Perugia) recounts the refined late Gothic civilization, placing side by side with the Madonna and Child of St. Dominic, a masterpiece by Gentile da Fabriano, the medals of Pisanello, exhibited for the first time in the museum itinerary. Gentile’s panel is the protagonist of another one of the Gallery’s novelties: the “Angeli musicanti” project, dedicated to works depicting instruments or even musical scores, finds space in the rooms thanks to directional bells, which will allow visitors to listen to the sound “produced by the works,” with highly suggestive effects. We then move on to Room 9, The Autumn of the Middle Ages in Perugia, where the refined figurative culture of the extreme Gothic period is represented, and then to Room 10(The Spring of the Renaissance: Beato Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli), which recounts the novelties of the Renaissance in the city with works such as Beato Angelico’s Guidalotti polyptych and Benozzo Gozzoli’s Pala della Sapienza Nuova.

The splendid loggia overlooking Corso Vannucci (Room 11, A Space Rediscovered: the Loggia of Alessi and the Sculptures of Agostino di Duccio) is one of the most significant outcomes of the redevelopment of the main floor of the Palazzo dei Priori designed in the mid-sixteenth century by Galeazzo Alessi of Perugia. Previously, this environment was “fragmented” by movable panels, which did not make possible an overall view of it. The elimination of these diaphragms recovered the unity of the architectural space, revealed by natural light and entirely enjoyable, thanks to the presence of comfortable seating. However, the loggia has not lost its exhibition function, allowing the narrative of the collection to continue thanks to the presence of Agostino di Duccio’s sculptures.

Then here is room 12, Giovanni Boccati and the figurative culture of the 15th century between Umbria and Marche, where some of the many works by Giovanni Boccati da Camerino preserved by the Gallery are displayed. Partly by virtue of his contacts with Florence and Padua, the Marche artist elaborates an original interpretation of early Renaissance innovations, where interest in antiquity and the scientific rendering of space take on bizarre and restless traits. In Room 13, Piero della Francesca’s The Polyptych of St. Anthony, we delve deeper into the great borough artist’s masterpiece, The Polyptych of St. Anthony. It continues in rooms 14 and 15(The Perugian Way to the Renaissance: Benedetto Bonfigli), devoted to Benedetto Bonfigli, official painter of Perugia’s institutions in the third quarter of the 15th century. His production is characterized by an underlying uniformity in which is embodied the bionomy “quality and industry,” typical of many artist-craftsmen of the early Renaissance. The selection of works sought to account above all for quality, representing the highest achievements of this master so important to the Umbrian city. Room 16(Perugino: The Golden Age) is the first of those dedicated to the man whom Agostino Chigi called “the best master of Italy.” The path that led the painter from Città della Pieve to be contended by the leading patrons of the time and to give birth to a true ’national language’ is summarized in this room, thanks to the works that marked his beginnings and first resounding successes: the celebrated Miracles of San Bernardino, the Pietà of the Farneto, theAdoration of the Magi, the cymatium of the Pala dei Decemviri, the gonfalons of Justice and Consolation, and the lyrical Annunciation Ranieri.

In Room 17, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, the career of this painter, who effectively embodies the combination of ’quality and industry’ in Renaissance art, is fully traced. Perhaps for this reason, too, his critical vicissitude has been marked by erroneous attributions that have led first to exalt, then to diminish his profile, finally leading to a more balanced recognition of the important role he played between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the Perugian context. Room 18(Art in Perugia in the Second Fifteenth Century: Bartolomeo Caporali) is dedicated to another protagonist of the second fifteenth century: before theexploits of Pietro Vannucci, the protagonist of Perugian artistic life in the second fifteenth century along with Benedetto Bonfigli was in fact Bartolomeo Caporali. The latter ran, together with his miniaturist brother Giapeco, a workshop devoted to a plurality of painting techniques, in which the major artists of Perugia of the time transited as pupils or collaborators. The works collected in this room trace Caporali’s complex stylistic evolution: from his beginnings under the aegis of Benozzo Gozzoli, witnessed by the Madonna and Child with Angels from Monteluce, to the more Verrocchio-esque phase represented by the Triptych of Justice. Room 19(Perugia and Paul III: the Sala Farnesiana), or the Room of the Governmental Congregation “for the state,” is rearranged, without the presence of works, to ensure its historical identity, making it a resting place where one can refresh oneself, thanks to the presence of comfortable seats. One then enters Room 20(Ductus. Roberto Paci Dal ò), where Roberto Paci Dalò has created in watercolor graphite and Indian ink Ductus: images and words that reconsider some watersheds of history and art in Umbria, offering the contemporary visitor suggestions, elements of reflection, formal remodulations capable of activating direct and intuitive mechanisms of knowledge.

In Room 21(Testimonies of Everyday Life), objects closely related to the exercise of governmental functions that took place in the Palazzo dei Priori, and Perugian tablecloths, respectively, are collected in two showcases. Room 22(Great masters in minor Umbria: Piero di Cosimo and Luca Signorelli) shows how in Renaissance Umbria even the most peripheral centers were enriched with works by great masters, such as the splendid Pietà by Piero di Cosimo and the Paciano Altarpiece by Luca Signorelli, respectively from the parish church of San Martino in Abeto di Preci, near Norcia, and from the village of the same name near Lake Trasimeno. Then comes the second room dedicated to Perugino, room 23(Perugino: his maturity and late activity), where works from the artist’s late production are on display, which has been stigmatized in the past for the uniformity of iconographic inventions and the repetition of compositional models, due not least to the reuse of the same cartoons. The works exhibited in this room, however, testify to how, even in his later years, the painter proves his stature by experimenting with techniques that allow him to achieve highly modern chromatic effects. Then we enter room 24(Pinturicchio and the Altarpiece of Santa Maria dei Fossi), dedicated to Pinturicchio’s great masterpiece, here exhibited together with a high-impact multimedia installation, which allows us to appreciate in a kaleidoscopic vision the infinite details of the work, otherwise impossible to grasp. Room 25, Raphael and Perugia, recalling how until the early seventeenth century at least six works by Raphael, who was linked to Umbria by virtue of his close working relationship with Perugino from a very young age, were preserved in Perugia, traces the painter’s presence in the city, collected in this room to testify to the fundamental incidence of his masterpieces for the developments of the local artistic scene. Then comes Room 26(A tormented commission: the Monteluce Altarpiece): the intimate space of an ancient tower house incorporated into the Palazzo dei Priori tells the troubled story of the altarpiece with theCoronation of the Virgin commissioned from Raphael by the Poor Clares of Monteluce. The predella panels made by Berto di Giovanni, part of the collection, will be joined by an extraordinary novelty: the tondo with the prophet David that decorated the capsa of the altarpiece, loaned to the museum by the private owner.

There is more talk of Perugino in Room 27(Perugino’s Legacy): the Perugino workshop of Pietro Vannucci nurtured the remarkable talents of Berto di Giovanni, Giovan Battista Caporali, Eusebio da San Giorgio, Ludovico d’Angelo Mattioli, and Giannicola di Paolo, represented here by some of the best works of their output. Room 28(Beyond Perugino: Bernardino di Mariotto and the unknown painter of Palazzo Pontani) discusses the Perugia of the 1630s, where Bernardino di Mariotto and the anonymous painter of the frescoes of Palazzo Pontanti worked, who, though without reaching high qualitative heights, became interpreters of the heterogeneous tendencies that ran through the panorama of a city still very much tied to the memory of Pietro Vannucci in those years. From room 29(Domenico e Orazio Alfani: da Raffaello alla Maniera), dedicated to the Alfani dynasty, we progress into room 30(Il secondo Cinquecento tra estetismo e devozione), which explores the two opposing but complementary artistic trends of this historical period. The first, which is more rigorously respectful of what was established in the Council of Trent regarding sacred images, inspires paintings characterized by clarity and compositional simplicity and aims to emotionally involve the faithful, bringing them closer to the deep spirituality emanating from the characters depicted, as is the case with St . Catherine of Alexandria in terracotta and the St. Catherine of Siena / de’ Ricci, recently attributed to Sister Plautilla Nelli. The other trend is that of an aestheticism that, while respecting the principles of the Counter-Reformation, is characterized by elegance, richness of color and refinement of composition, as is evident in Giovambattista Naldini’s Presentation of Jesus in the Temple and Ferraù Fenzoni’sAnnunciation and Prophets.In Room 31(Two Examples of Caravaggism in Umbria), masterpieces by Orazio Gentileschi ( Saint Cecilia Playing the Spinet) and Valentin de Boulogne (the Noli me tangere and Christ and the Samaritan Woman) testify to the spread of Caravaggio’s language in Umbria in the first half of the 17th century. Rooms 32 and 33(The Martinelli Collection and the Roman Baroque) are devoted to the Roman Baroque and its protagonists: A number of works by Gian Lorenzo Bernini stand out, including one of his rare paintings, the Portrait of a Gentleman, an autograph sketch for a “ligato” Christo, the two crucifixes of the type of the Living Christ and the Dead Christ made for the altars of the Vatican Basilica, as well as two works by Pietro Bernini, in which the hand of a very young Gian Lorenzo is perhaps also recognizable. All come from the collection of Valentino Martinelli, an art historian and collector, a fine connoisseur of the period in question who, by bequest in his will, donated his art collection (more than one hundred works) to the Municipality of Perugia in 1997.

Room 34(Aldo Capitini) is linked to the memory of Aldo Capitini (1899-1968), who lived, together with his family (his father, as he himself recounts, was the “keeper of the bell tower”), in a small apartment that included rooms on the top floor of the Palazzo dei Priori, recently recovered and restored. In these rooms Capitini worked hard, weaving extensive international relations and writing philosophical, pedagogical, and political essays on nonviolence, direct democracy, religious experience, vegetarianism, and conscientious objection. We then come to Room 35(Pietro da Cortona), dedicated to the works of the third great Baroque protagonist, besides Bernini and Borromini, namely Pietro da Cortona. Thus the large altarpiece with the Nativity of the Virgin, in which the sacred episode is transformed into an everyday scene of domestic intimacy, and two of the many works dedicated by the artist to St. Martina, for whom he had a special veneration, having found the body of the martyr saint during the rebuilding of the church of Saints Luke and Martina in Rome, are on display: the terracotta model for theApparition of Our Lady to St. Martina, from the Martinelli collection, and the beautiful panel painting of Our Lady and Child with St. Martina.

We move toward the conclusion in rooms 36 and 37( Seventeenth-century classicism) with some high points such as the Holy Family with Saints Anne and John the Baptist by Gian Domenico Cerrini, known as Cavalier Perugino, where the influences of Emilian classicism are evident but also the peculiar stylistic signature of theartist, characterized by the harmony of chromatic and compositional choices, and the Purification of Mary by Andrea Sacchi where the scene, although crowded, is rigorously constructed and enlivened by the use of color and luministic solutions, used to highlight the fundamental elements of the composition. Room 38(From the Late Baroque to the Early Nineteenth Century), once used as the Priors’ refectory, houses a series of works documenting the evolution of taste between the second half of the seventeenth century and the early nineteenth century. The eighteenth century is represented in its different souls, from the scenographic Rococo of Corrado Giaquinto’s skies and luminosities, to the Arcadian sensibility of Sebastiano Conca’s canvases inspired by Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, to the almost “purist” classicism of Pierre Subleyras that seems to anticipate Neoclassicism’s quest for formal simplification. An exponent of the latter current, French painter Jean-Baptiste Wicar left Perugia in the 19th century with a series of large-format works and some portraits, conducted to perfection like the two in the room, from the Carattoli collection. Finally, closing in Room 39(The Twentieth Century) with the aforementioned works by Gerardo Dottori, Alberto Burri, Piero Dorazio and Adalberto Mecarelli.

|

| Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria reopens with new layout and many new features |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.