Mondrian upside down, the discovery is by an Italian artist. Here's how he got there

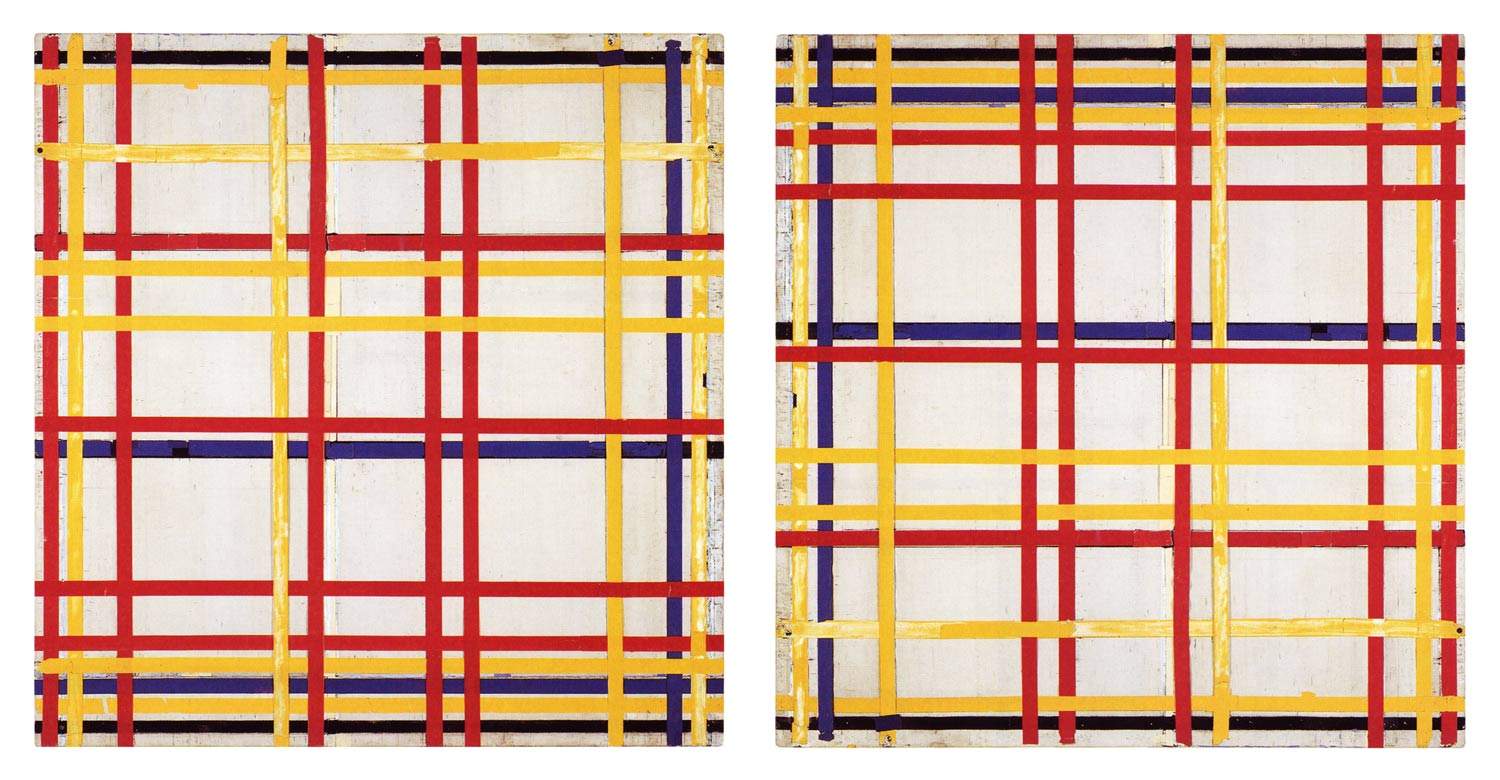

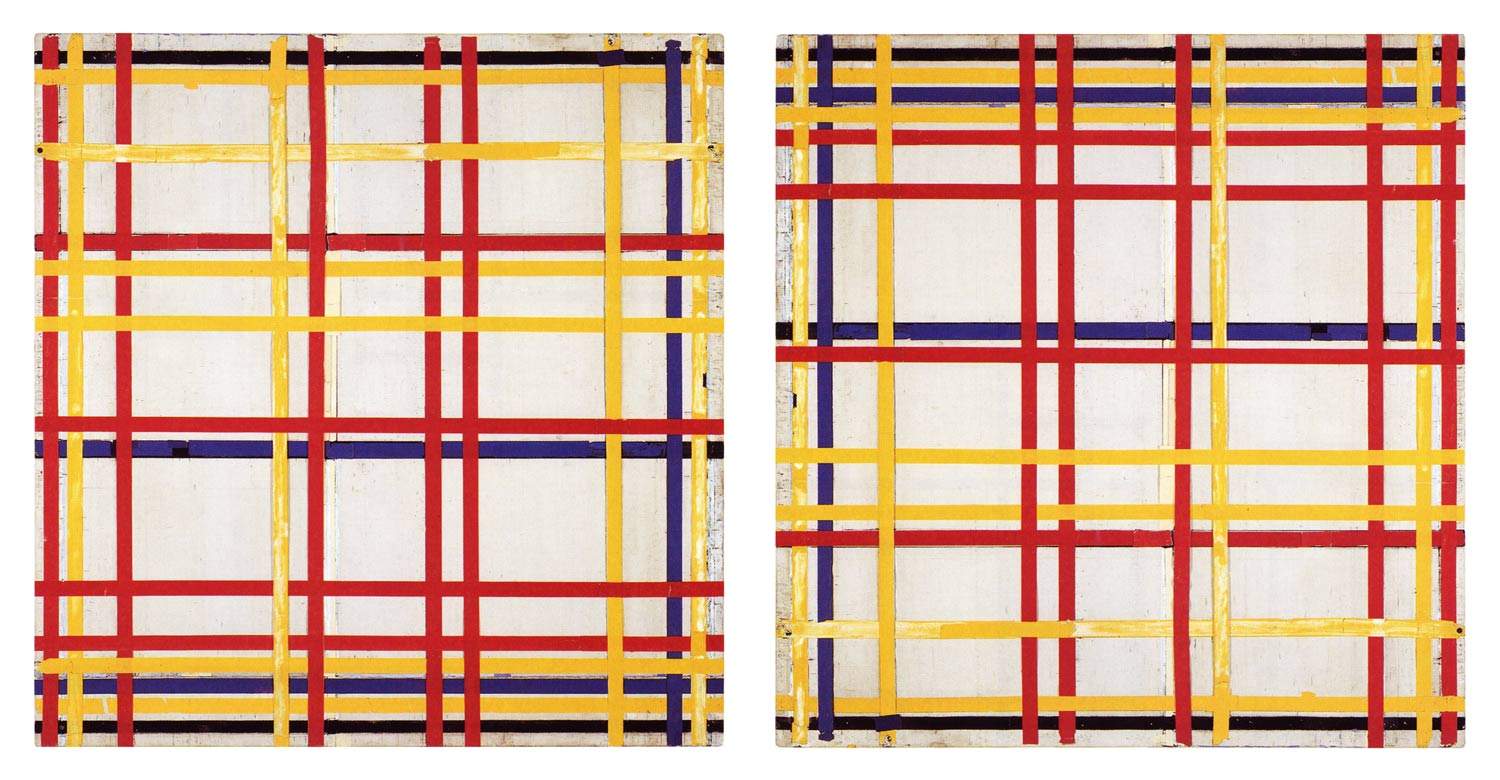

News of Piet Mondrian’s 1941 painting New York City 1, displayed upside down for more than 75 years at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, Germany, has gone around the world. The announcement was made by curator Susanne Meyer-Büser at a press conference, however, during which it was explained that the painting will remain hanging as it has since 1945, that is, with the grouping of yellow, red and blue stripes at the bottom and not at the top as it originally was.

The discovery, as anticipated, bears the signature of an Italian artist, Francesco Visalli, who as early as September 2021 sent an email to the museum’s director, Anette Kruszyinski, attaching studies and period images to support the theory. Visalli, who is often devoted to researching abstractionism and Mondrian’s art in particular, found some useful documents on how the work was originally displayed. The research started with a work, Rhythm in Straight Lines (inventoried as B311 in Joop Joosten’s catalog raisonné), which Mondrian began between 1935 and 1937 when he was in Paris (one can see this work in Rogi André’s 1937 photo of Mondrian’s studio on boulevard Raspail). Rhythm in Straight Lines represents the preliminary phase of the later New York City 1 and was published on several occasions, first in the magazine Das Werk (No. 8, 1938), in Max Bill’s article entitled Uber konkrete Kunst.

It is then presumed that during 1938 Mondrian delivered the work to gallery owner Valentine Dudensing in New York. After moving to New York in October 1940, Mondrian made a series of changes to the painting in 1942, effectively completing the work as we know it today. “For many years (and still today),” Visalli explains, "it was believed that the work in its ’first state’ had never been exhibited and that the first exhibition was of the final work, which occurred in 1945 with the first retrospective at MoMA in New York. During my research I was able to ascertain that the work in its ’first state’ was exhibited in 1940 at the Baltimore Museum of Art in the exhibition entitled Modern Painting, Isms and How They Grew (January 12 to February 11). It was probably a loan from the Valentine Gallery." The work was published in the exhibition catalog, found by Visalli at the Frick Collection Library, under the title Abstraction. Visalli also found a photo of the installation in the Baltimore Museum of Art’s digital collection.

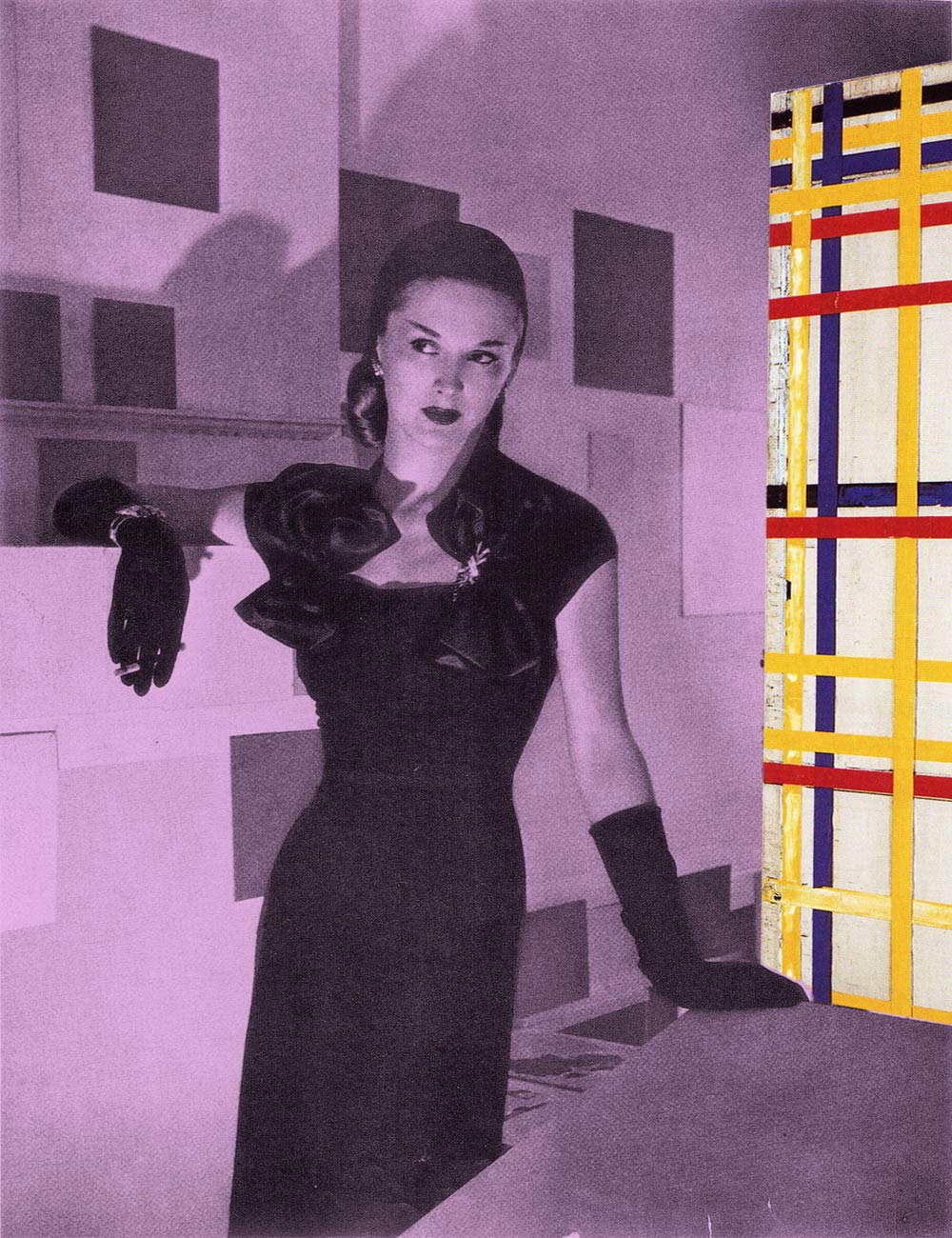

New York City I was later published as B300 in Joosten’s catalog raisonné. “Each of Mondrian’s works,” Visalli explains, “has its own precise orientation and in general it is the position of the signature that determines it, basically you can’t go wrong. But, as is well known, in this particular work the signature is not present and has always been oriented with the thickest lines facing downward.” The definitive proof, however, is a photograph taken a few days after Mondrian’s death by Harry Holtzman, who used the painter’s studio to take some pictures with Swedish supermodel Lisa Fonssagrives, for a fashion report in Town and Country magazine. These images were later published in the June 1944 issue in an article titled Black is Right: one of the photographs shows Fonssagrives posing next to the work New York City I. Only part of the work is visible and it probably rests on an easel just as Mondrian left it. And as can be seen from the photograph, the work has the grouping of stripes at the top: this thus appears to be the orientation Mondrian had intended for the painting.

Visalli’s discovery thus makes it possible to properly appreciate the orientation Mondrian had thought of for his work: it may seem like a minor detail, but for Mondrian it was fundamental, since the balancing of the lines had for him not only a “practical” function that had to do with the viewer’s perception (and thus, according to the way the artist arranged the lines, he intended to suggest to the viewer of the painting certain sensations: tranquility, speed, dynamism, turbulence, and so on), but also symbolic (vertical lines, for example, represented the masculine and horizontal lines represented the feminine).

The

The

The work as it has been

The work as it has been

|

| Mondrian upside down, the discovery is by an Italian artist. Here's how he got there |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.