Working with clay: the seeds of Arianna Cordiviola. "A wonderful material."

Arianna Cordiviola has been creating interesting works with clay for years. She was born in Carrara in 1977, where she refined her artistic sensibility at the Artemisia Gentileschi Art School. She continued her education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara, graduating with a thesis dedicated to Japanese printing, under the guidance of Prof. Giovanna Bombarda. The academic path marked the beginning of a journey toward the exploration of matter, with a particular focus on clay and clay-like materials. Since those years, Arianna Cordiviola has developed a predilection for the coarser, semi-refractory and refractory varieties of clay, with the addition of oxide or all-natural pigments, as an expression of a research on the material and its transformation. In 2005, he participated in the Biennale of the students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara, one of the first occasions when his works were exhibited to the public. In the following years, his work became increasingly centered on experimentation, leading in 2013 to the creation of his own studio and exhibition space in Sarzana. In this interview, we hear about his art.

NC. What was your educational background and how did it influence your art practice?

AC. My course of study has been varied. I started with classical high school because I had a strong interest in the humanities and wanted to deepen that aspect of knowledge. Later I chose to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts where I began to experiment seriously, pursuing a practice I had already undertaken on my own, working with materials, particularly clay. The material became central to my artistic journey, and I still use it today. I think my passion for clay has deep roots in my childhood. I lived with my grandmother for many years, and there, not having many toys, I used to spend my time creating with what I had on hand. I remember that when it rained I would collect mud from puddles or outdoor containers and then mix it with crushed stones or pieces of terra cotta to form small creations that I would let dry. My grandmother, who was a humble and simple person, always left me free to experiment, and those moments have stayed with me. From there my passion for manipulating materials was born. My first real course related to ceramics was when I was about 15 or 16 years old. It was the first step toward what would become an artistic path that I still cultivate with passion.

Over the years you have delved into the use of clay and raw, semi-refractory and refractory clay materials, often mixed with oxide or natural pigments. What fascinates you about these materials?

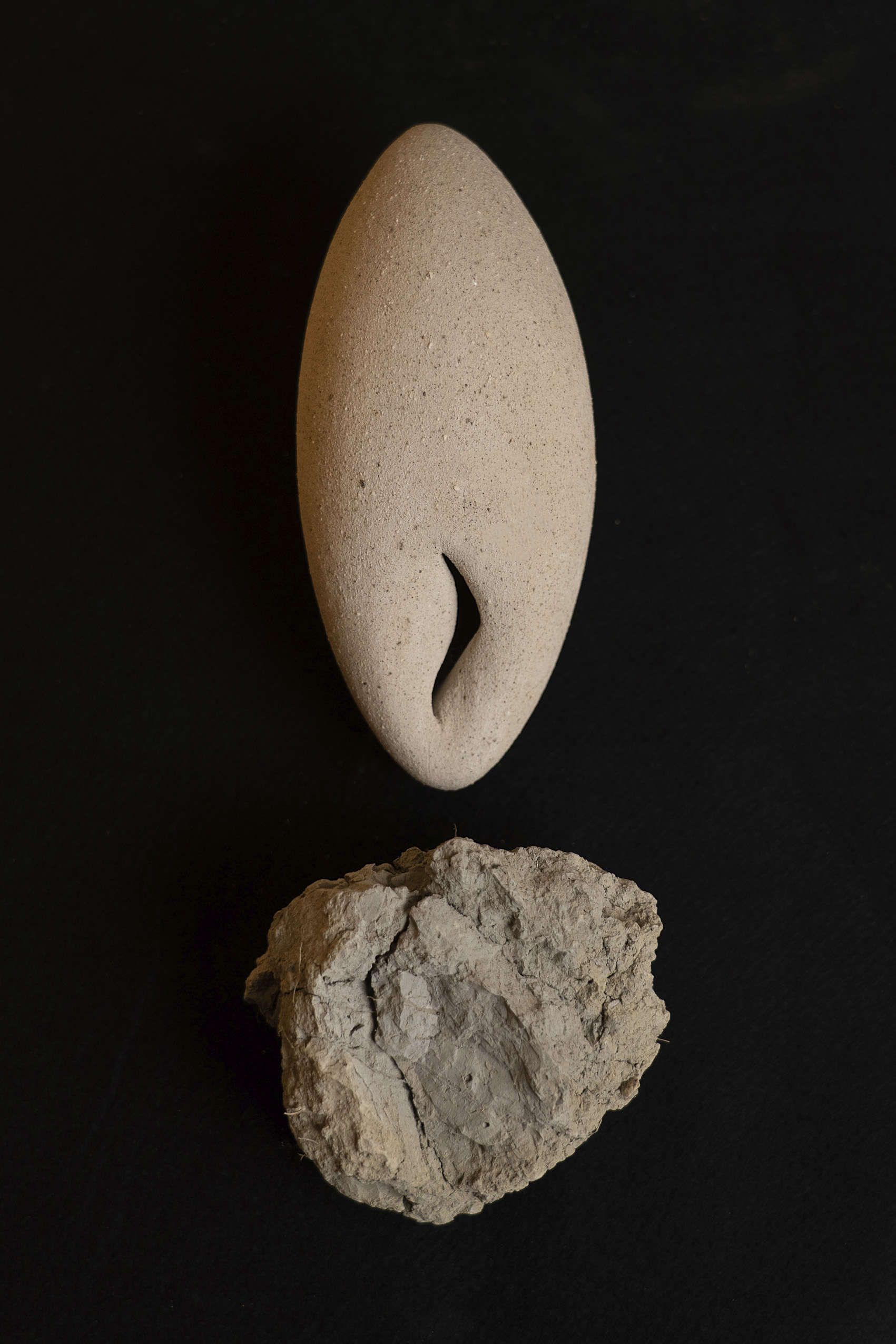

The materials I use, starting with clay, are simple and poor, but that is what makes them so special. In an age like ours, attributing value to materials readily available in nature gives added meaning to the work of art, be it a sculpture or a vase. The materials enrich the work, give us a new code for reading and interpretation. What fascinates me is the idea of working with clays collected directly from nature. There are many places, such as old abandoned quarries or riverbeds where clay settles and can be found with a careful look. Each clay has its own identity, and I like the idea of telling the soul of those places through the works I make. When I search for natural clay, I take with me the experience of discovering the place. The finished work, besides being the fruit of my labor, becomes a kind of genius loci, the story of a specific place, with its landscape and geography. The material I choose embodies the history of those places as if each sculpture or creation is a narrative of the very land from which it was born.

Your works are made with a focus to manual skills and traditional materials such as clay. In your opinion, where does the work of the artisan end and that of the artist begin? How do the two roles intertwine in your practice?

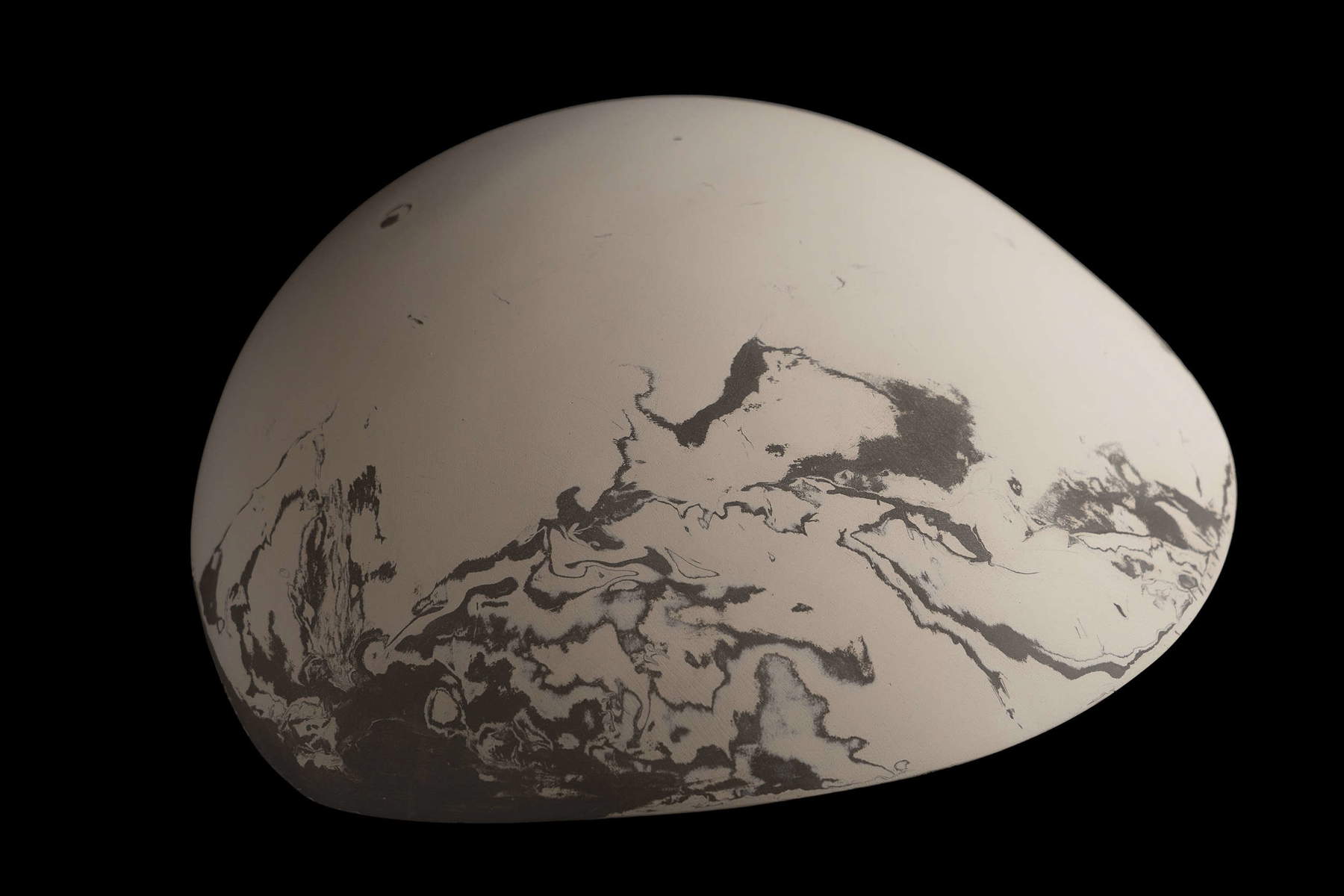

In my practice there is a component that I perceive as strongly artisanal. When I work mostly on the potter’s wheel for example creating vases, I experience the process as a form of meditation. It is very manual work that requires concentration and patience and brings me to a state of great tranquility. Here, this craft dimension is for me an essential part of my artistic and creative approach. Next to this aspect then there is another component of my work that I consider more sculptural. The forms I make are often very stylized, synthetic and essential, almost pure, and are inspired by natural forms.

How important is it to you that the material you choose communicates on a sensory level, as well as visually?

Touch is one of the fundamental characteristics in my artistic research because although the first impact with a work is visual, sight is only the beginning. We certainly observe and encode the work through our eyes, but there is a moment when a significant transition occurs that involves touch. In addition to reading the work with sight, touch comes into play by allowing us to perceive imperfections, details, and variations in materials. All these elements, such as different grain sizes or intrusions of rock or sand, generate different tactile sensations. Some materials are smooth and silky, like certain clays, and caressing them is a pleasure that conveys a feeling of well-being. For me, touching materials is rewarding and creates a deep connection on an emotional level as well; I might call it a sense of reassurance and comfort.

Your works explore the relationship between forms, materials and nature. What inspired you to create giant seed sculptures?

The dialogue arose from a deep connection between my introspective side and the side related to nature. Years ago, I felt the need to express an inner synthesis, a form that was both symbolic and sacred yet essential. I found this synthesis in simple forms and especially in that of seeds. I remember in particular a trip to Ireland many years ago, during which one seed in particular caught my attention because of its fascinating shape. Despite the impression it left on me at the time I did not develop the idea of artistic design. Only in time did that form become a sculpture. It was only when I perceived that that was the right form that I resumed work. So I started with drawings, sketches and later made small seed sculptures, each with slightly different and larger shapes. From there began a real research both material and formal always inspired by nature. Every journey becomes an opportunity for me to observe and pick up new forms in nature, it is a process that I continue to explore and develop.

What do seeds represent to you? Why are they often present in your sculptures?

The seed represents for me a deep core, a connection to something primordial. There is a strong connection with the theme of birth because it carries with it a vast symbolism related to the stages of life: birth, death and rebirth. This cyclical nature therefore has a deep meaning because it recalls continuous transformation. The seed is a form that I feel is an inner place, almost a non-place, and it represents an animic dimension for me. It is as if I am trying to give a tangible form to a deep feeling, linked to the most intimate part of the human being. While dealing with human themes, the works are also animated by a sense of sacredness. Through the process of simplifying forms I try to remove the superfluous, to get to the essence. On this path, subtraction becomes enrichment, and the synthesis of forms leads me toward greater essentiality. The creative act for me is a continuous search for balance between inner complexity and formal simplicity and where each work is the result of this profound dialogue.

Is there therefore a message about time in the works that include sprouts?

Certainly they have a similar function as incubating forms, also because as we were saying they reflect the aspect of waiting. I like to think that with time this process of incubation leads to a transformation, as if the seeds break and from that split a new form emerges: a form that has its own path, its own nature and its own evolution, and then goes back to being a seed.

How many hours of work do your works require?

Clay requires a different approach than other materials, mainly because of its artisanal and artistic nature. For example, when you work on a potter’s wheel you can create shapes such as vases or containers in a relatively short time. However, even though the modeling is fast, the complete process follows a timeline that is not linear because there are steps that must be followed. Clay for example has its own timeframe: once shaped, it must go through several stages of drying, shrinkage and firing. It requires pauses and waiting between each step. Unlike materials that allow continuity in the work such as wood, clay must rest and dry slowly to prevent damage. It has to wait for it to lose its water before it can be fired, and only then can it move on to the actual firing, which can take place in different types of kilns and at different temperatures. Despite these waiting stages, clay is wonderful to work with because of its plasticity and malleability; it is much easier than harder materials such as stone. At the same time, however, it requires care and patience because it cannot be forced or twisted. It must be followed in its natural process of transformation.

For the future will you continue to explore the topic of seeds or do you also have new projects in mind?

At the moment I feel the need to open up and evolve the central forms of my work although I believe that for now clay, which has always given me so much, continues to offer me the opportunity to explore new avenues. It is a living material that stimulates continuous and slow research; it is a process that still fascinates me deeply. Although I am approaching new directions, for the moment I am attracted to the slow pace and transformations that this material allows me to experience. In the future I would like to expand this kind of language, perhaps exploring other materials as well. For now I remain open to all the possibilities that this research and curiosity offer me.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.