From February 15 to June 21, 2020, the San Domenico Museums in Forli will host a major exhibition dedicated to the figure of Ulysses: with works from antiquity to the present day, the exhibition, entitled Ulysses. Art and Myth and curated by Fernando Mazzocca, Francesco Leone, Fabrizio Paolucci and Paola Refice, will investigate the figure of the Homeric hero according to how it has been read in the various eras and according to how it has been interpreted by different artists. With an impressive body of works, the exhibition will establish relationships between art and myth by leading the visitor along a journey that spans more than two thousand years of history. We spoke about the exhibition with curator Francesco Leone, who explained some of the motivations behind the exhibition and gave us some previews of what we will be able to see in Forli. The interview is edited by Ilaria Baratta.

|

| John William Waterhouse, Mermaid (1900; oil on canvas, 81 x 53 cm; London, Royal Academy of Fine Arts) |

IB. From February 15 to June 21, 2020, we will see at the San Domenico Museums in Forli the exhibition Ulysses. Art and Myth. How did the idea for this exhibition come about?

FL. It is a project that has had a long gestation. We have been working on it for about three years. The idea came from Gianfranco Brunelli, Director General of the Scientific Committee of the Fondazione Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì. He discussed it with Antonio Paolucci, Chairman of the Scientific Committee, with Fernando Mazzocca and myself. Soon after, Paola Refice and Fabrizio Paolucci joined the roster of curators. We began working on it in parallel with the project that led, last year, to the exhibition Ottocento. Larte dellItalia tra Hayez e Segantini.

The presentation reads, “Ulysses is us, our restlessness, our challenges, our desire to risk, to know, to go further”; could you better define this concept?

All journeys are symbolic of a quest: into the deep mysteries of creation and into the equally deep mysteries of our inner selves. Ulysses’ is even more so. The Homeric hero wanders to return home, that is, to be reunited with his origins. But to do so he must face a series of events in which all the feelings, aspirations, and anxieties of the human being take shape from time to time. These states of the soul belonged to the archaic Greek man as they do to the man of today. Even to return to Ithaca Odysseus is forced by Circe to descend into the world of the dead. What challenge, and what fear, can be for a man greater than this? In theAde Odysseus sees his mother and old battle buddies again. In the end it is a journey that reflects an inner quest in almost psychoanalytic terms. Therein lies all the incredible modernity of the Odyssey. I will say more. After the Holy Scriptures, the Odyssey is the first text of antiquity in which it concretizes for us a conception of narrative that is the same on which our notion of history, our way of having awareness of things that have passed and consequently of our consciousness, individual and collective, is based. This is why Ulysses is the father of us all. His challenge to the unknown, with all its enthusiasms and all its fears, his reflection on the supernatural, on the metaphysical element that surrounds us (be it the gods or the Sirens) are the same ones that have led modern man to cross his natural boundaries, even to the conquest of space to get, as the Homeric principle of the famous television series Star Trek goes, where no man has ever gone before.

The myth of Ulysses has become universal and has been addressed in Western culture in every artistic form, as well as in numerous literary works. So, it is one of the most famous cases where art and literature are mixed with myth. How do you think the relationship between art and mythology can be defined? How much do they influence each other?

Mythology has always been an incredible reservoir of images and themes for the visual arts, as well as for literature. After all, if history rationalizes human experience, myth is nothing more than a primary, and therefore universal and timeless, form of understanding our surroundings. It is a primordial and anthropocentric explanation, projected into an ideal sphere, of the world with respect to man, his psyche and his feelings. And so over the millennia the arts have made use of the myth of Ulysses to nest in it from time to time in paradigmatic terms the culture of an era, with all its ambitions, passions, anxieties and symbolic translations.

Through the different representations of the Ulysses myth over the centuries, is it possible to understand the dominant sentiments of an era?

Absolutely! For a good part of the modern era Ulysses is a hero who performs epic deeds; a valiant man whose deeds are brought back into the eternal realm of history. And as such he is celebrated in the figurative arts between the 16th and 18th centuries. Then in the course of the nineteenth century, with the rise of individualism, symbolism and new discoveries about the psyche and states of mind, Ulysses becomes the protagonist of a journey that symbolically exemplifies the existential aspiration to a distant Greekness, tinged with primitivism, felt as irretrievably lost and as such yearned for with nostalgic attitude as an original place linked to the universality of myth and the mystery of the beginnings to be contrasted with modern progress and a civilization that seemed to have reached, like Ulysses at the Pillars of Hercules, the boundaries of its millennial history.

Think of Odysseus’s encounter with the monstrous Sirens, hybrid beings half-woman and half-bird (or, later, half-fish), polymorphous double-crossers who divert sailors from the right path. Homer turns his attention exclusively to their divinatory qualities. Sirens, like muses and sibyls, know everything on earth that has happened and will happen. Their song leads to absolute knowledge that projects man’s finiteness into an irrepressible dimension that is proper to the divine sphere. In the sirens’ song lurks the human being’s yearning for knowledge. After their great figurative diffusion in antiquity (as a symbol of knowledge) and then in the Middle Ages (as an allegory of sin), from the 16th century onward these supernatural beings disappeared from the artistic scene, only to make a powerful comeback in the second half of the 19th century. This was because the artistic imagery of that period was literally subjugated by the universal, timeless and solutionless enigma of their bewitching song, into which poured the dilemma of every man of all times: the search for a landing place and the awareness of the inevitability of limitation or the enthralling longing for boundless knowledge, fatal in its immensity. And then in the sirens as fish-women symbolism transposed the modern theme of the femme fatale that had so much importance in the arts and literature of the second half of the nineteenth century. These are the same years in which female figures are extrapolated from the tales of the Odyssey as absolute protagonists: Circe, Calypso, Nausicaa, Leucothea, Penelope are the polysemy-rich translates of a complex, sophisticated and multifaceted culture. You think that in 1897 Samuel Butler published in London a volume(The Authoress of the Odyssey) in which he postulated, to much acclaim, that the author of the Odyssey was not Homer but a very inspired young woman who lived in Trapani around theXI century B.C. This was because in the Odyssey’s economics it seemed to him evident (and rightly so) the preponderance of the female element over the male.

According to what was preannounced, the exhibition intends to be a great journey of art (and not only in art), including works from antiquity to contemporary film art. In the face of such a vast theme, by what criteria were the works on display selected?

The more than 250 works that will be on display in the exhibition have been selected in order to give an understanding of what impact the tale of Ulysses has had on each era: antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, neoclassicism, the nineteenth century and the twentieth century. In each of these phases of Western civilization the rereading, and often the related rewriting, of the Odyssey profoundly marked the worldview of those periods. You think of Dante’s Middle Ages. In Canto XXVI of the Inferno, lAlighieri completely reinvents the summary of Odysseus’ story. He does not return home to Penelope but sets out on a final and fatal journey beyond the Pillars of Hercules that will lead him and his companions to death. For the Christian Middle Ages, the absolute knowledge whose longing grips Ulysses (but perhaps Dante himself) belongs to God, and the Homeric hero in that quest beyond all limits can only find death. So we have tried to choose works that are representative of the profound influence that the Odyssey has exerted on the various epochs of Western culture over three thousand years. But at the same time we wanted to build a narrative path full of fascination and suggestion in which the visitor will seem to be led by the hand into the plots of Odysseus’ tale. For the curious visitor it may be a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

What, in your opinion, are the most significant works? Will they all be well-known works or will some new ones be presented?

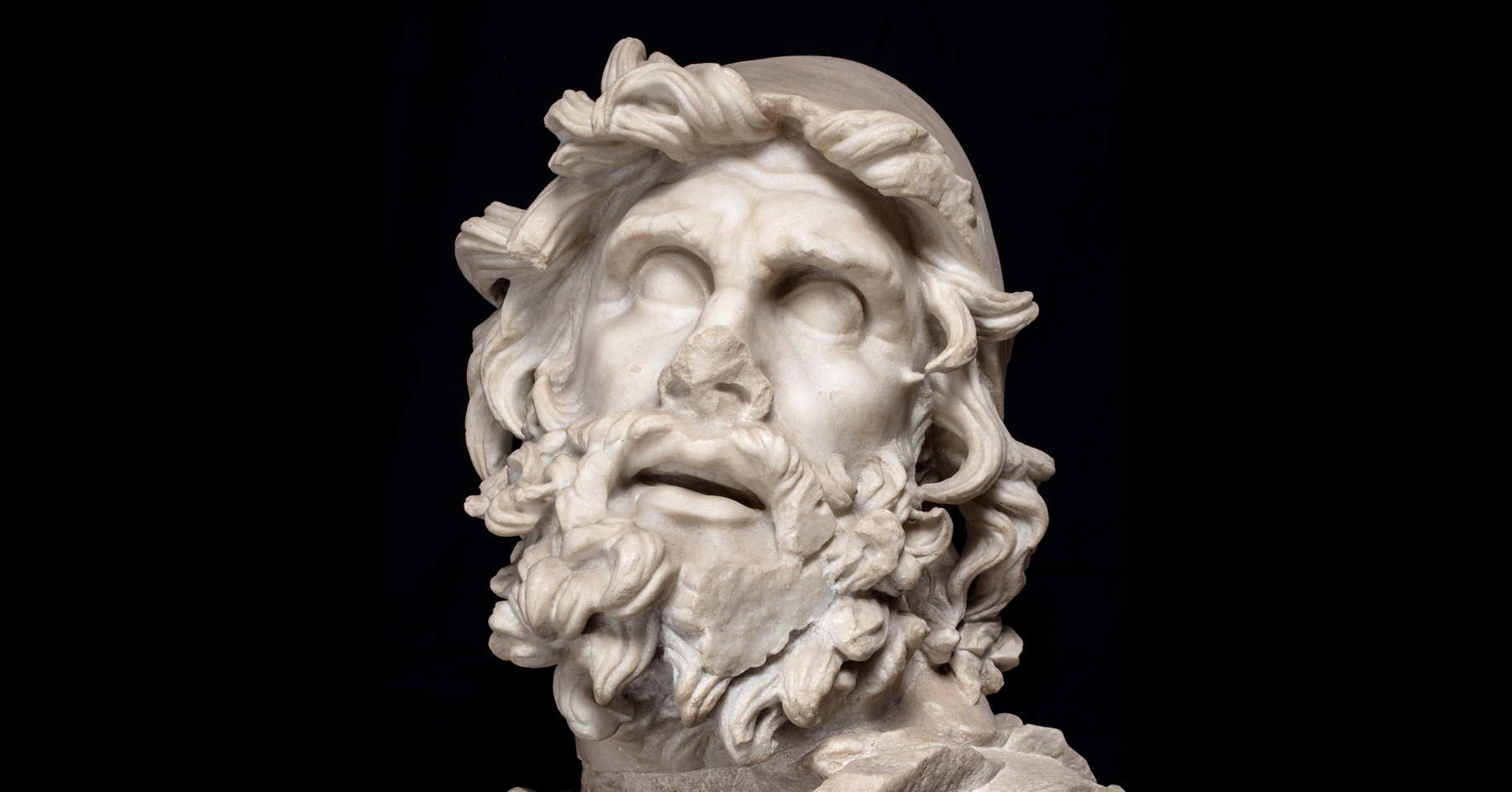

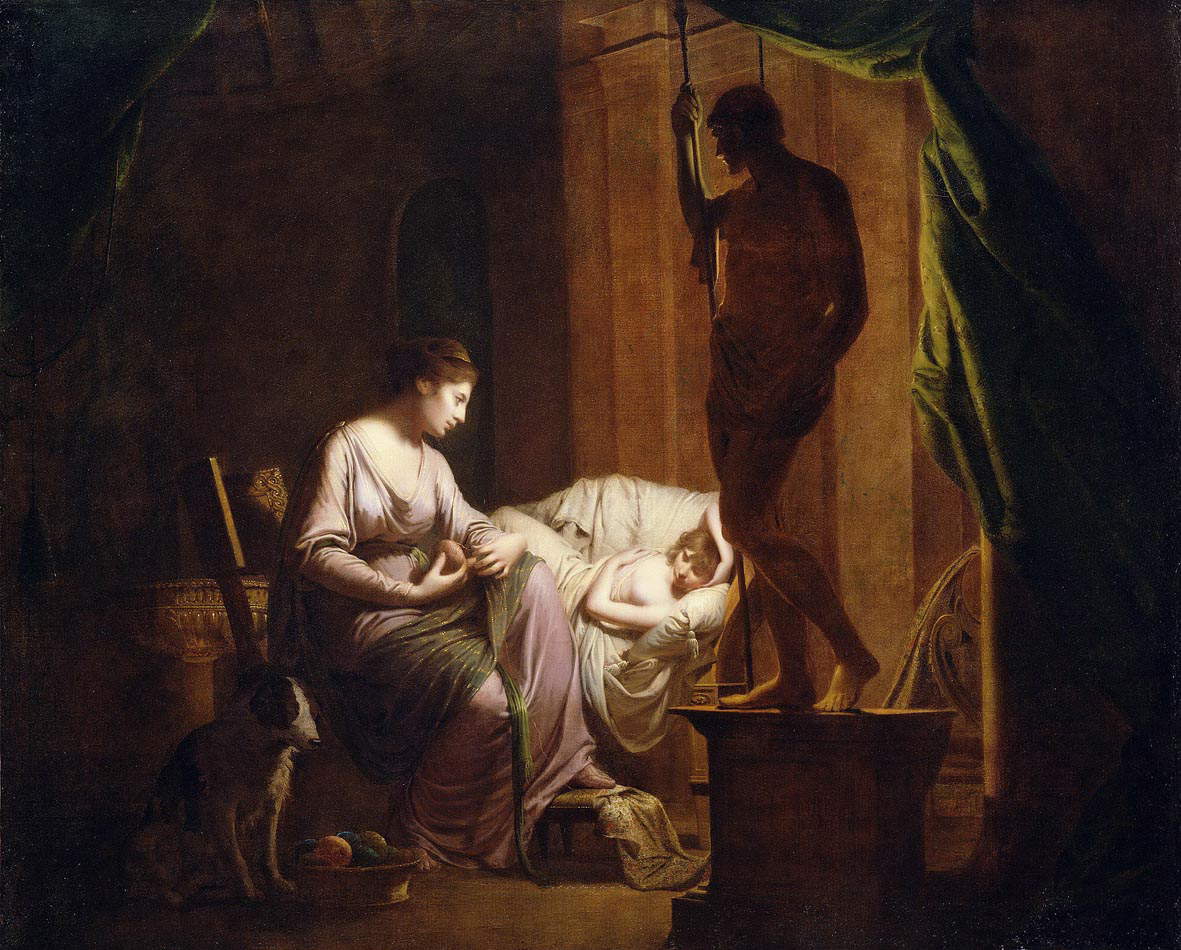

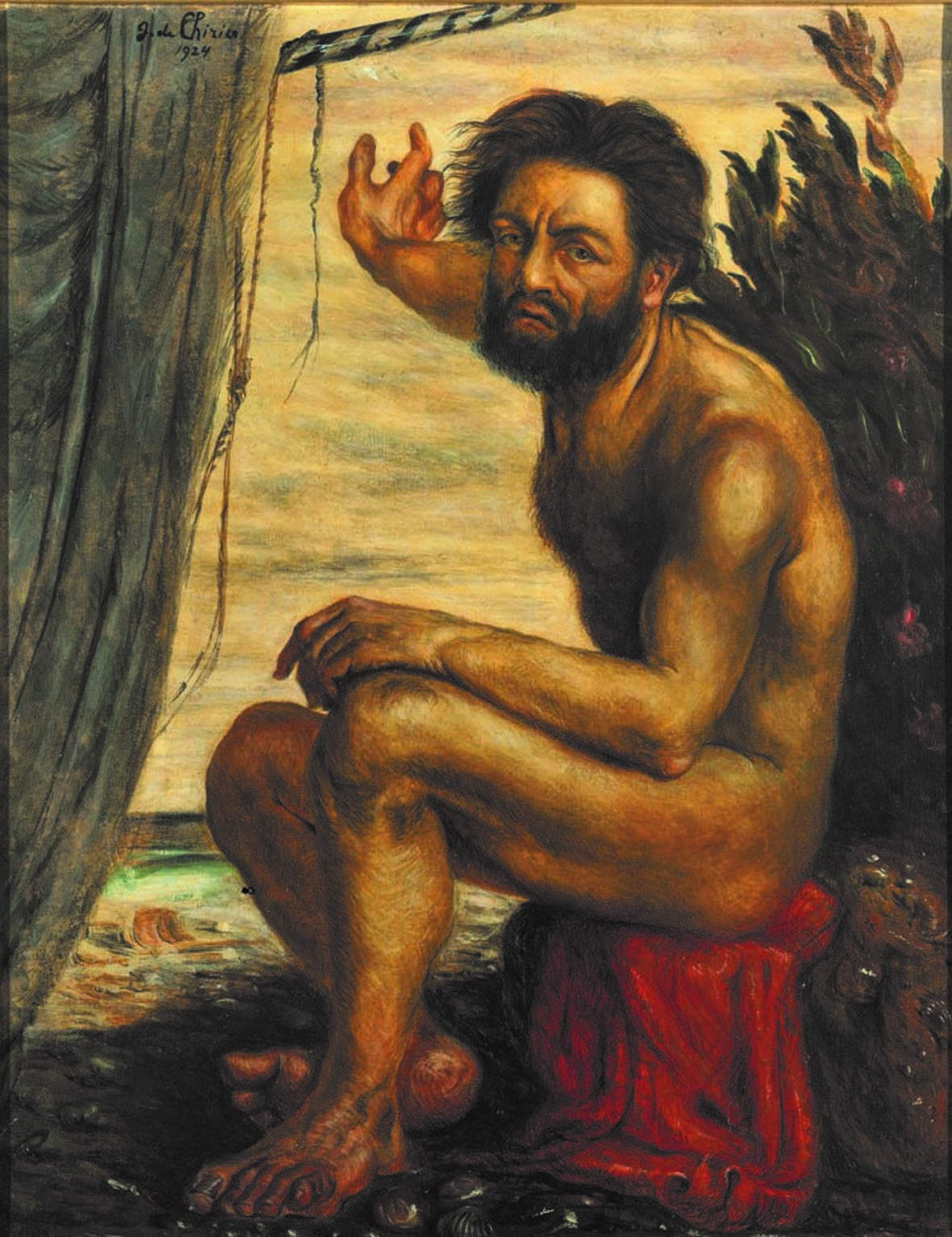

There will be many new works in the exhibition, works that have never been exhibited, masterpieces that have rarely left their locations, iconic images such as the famous head of Ulysses from the 1st century AD from the villa of Emperor Tiberius in Sperlonga. At the beginning of the exhibition, for example, in the monumental spaces of the Church of St. James, visitors will even be greeted by an Achaean ship from the 6th-5th centuries B.C. over 11 meters long. The ship, found in the Gulf of Gela, reconstructed and restored in a complex operation for the exhibition, is surrounded by the deities of the Olympus (incredible examples of ancient statuary) who facilitated Odysseus’ return journey. And all together these deities return in aenormous four-meter base painting by Peter Paul Rubens brought over from the collections of Prague Castle. Along with other very important pieces of archaeology we will display two of the frescoes detached from the Roman Domus on Via Graziosa in Rome. They are paintings from the first century B.C. preserved in the Vatican Museums, from which, however, they never leave. It will be a unique opportunity to admire them. After a series of priceless medieval illuminated manuscripts relating to Dante’s meeting with Ulysses, we will be immersed in the events of the Renaissance, among works by Liberale da Verona, Domenico Beccafumi, Parmigianino, Dosso Dossi, Pellegrino Tibaldi and many others. In the seventeenth century to emerge is the figure of Circe among paintings by Guercino and Grechetto. While among the works of the Neoclassical period, paintings by Johann Heinrich Füssli, Anton Raphael Mengs, Pompeo Batoni, James Berry, Joseph Wright of Derby, Angelica Kauffmann, and Francesco Hayez stand out. Among the artists of the mid-nineteenth century, the names of John William Waterhouse, Max Klinger, Giulio Aristide Sartorio and absolute must-see discoveries such as that of the Croatian symbolist Bela Čikoš Sesija stand out. Along with those of Ivan Meštrović, Alberto Savinio, Scipione, Corrado Cagli and Leoncillo, a prominent presence in the twentieth century is that of Giorgio de Chirico. Born in Volos, Greece in 1888, more than any other artist of the 20th century de Chirico felt himself to be a direct descendant of Ulysses in the name of Mediterraneanity.

What should we expect from this exhibition and what message does it intend to communicate to visitors?

Visitors should expect an unprecedented experience. A journey, like that of Ulysses, in search of our ancient origins lost in the fabled legends of myth. The figure of Ulysses has dominated Western imagery for three thousand years, but perhaps today more than ever his sea voyage along the Mediterranean routes can be considered relevant.

|

| Roman art, Ulysses (1st cent. AD; marble, 39 x 47 cm; Sperlonga, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Domenico Beccafumi, Penelope (1519; oil on panel, 84 x 48 cm; Venice, Pinacoteca Manfrediniana del Seminario Patriarcale) |

|

| Pieter Paul Rubens, The Olympian Gods (1601-1602; oil on canvas, 204 x 379 cm; Prague, Castle) |

|

| Joseph Wright of Derby, Penelope Unravels Her Canvas by the Light of a Candle (1783; oil on canvas, 106 x 131.4 cm; Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum) |

|

| Lèon Belly, Les Sirènes (1867; oil on canvas, 363 x 300 cm; Saint-Omer, Musée de lhôtel Sandelin) |

|

| John W. Waterhouse, Circe envious (1892; oil on canvas, 180.7 x 87.4 cm; Adelaide, Art Gallery of South Australia) |

|

| Giorgio De Chirico, Ulysses. Self-Portrait as Odysseus (1922-24; oil on canvas; Private collection) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.