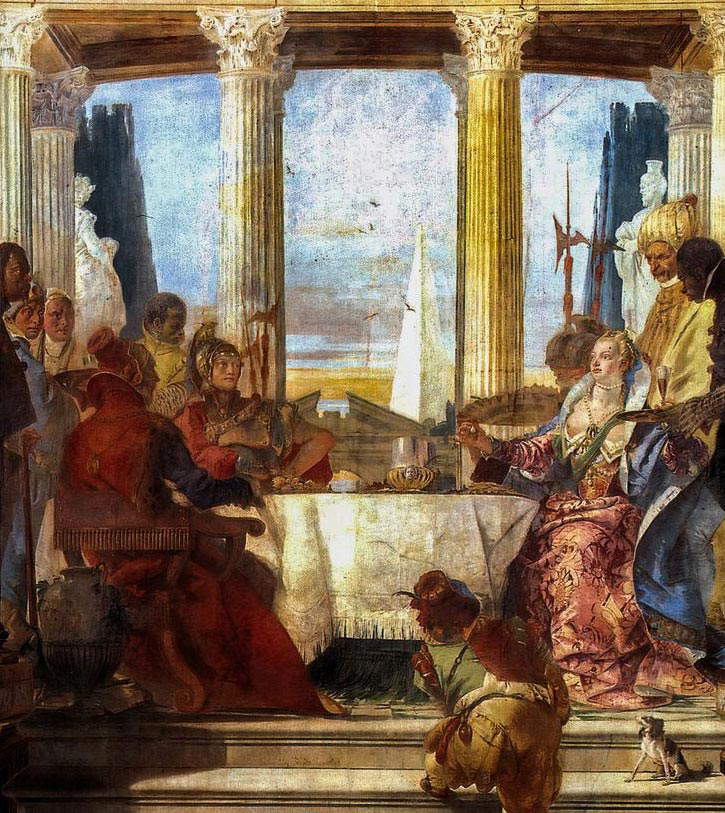

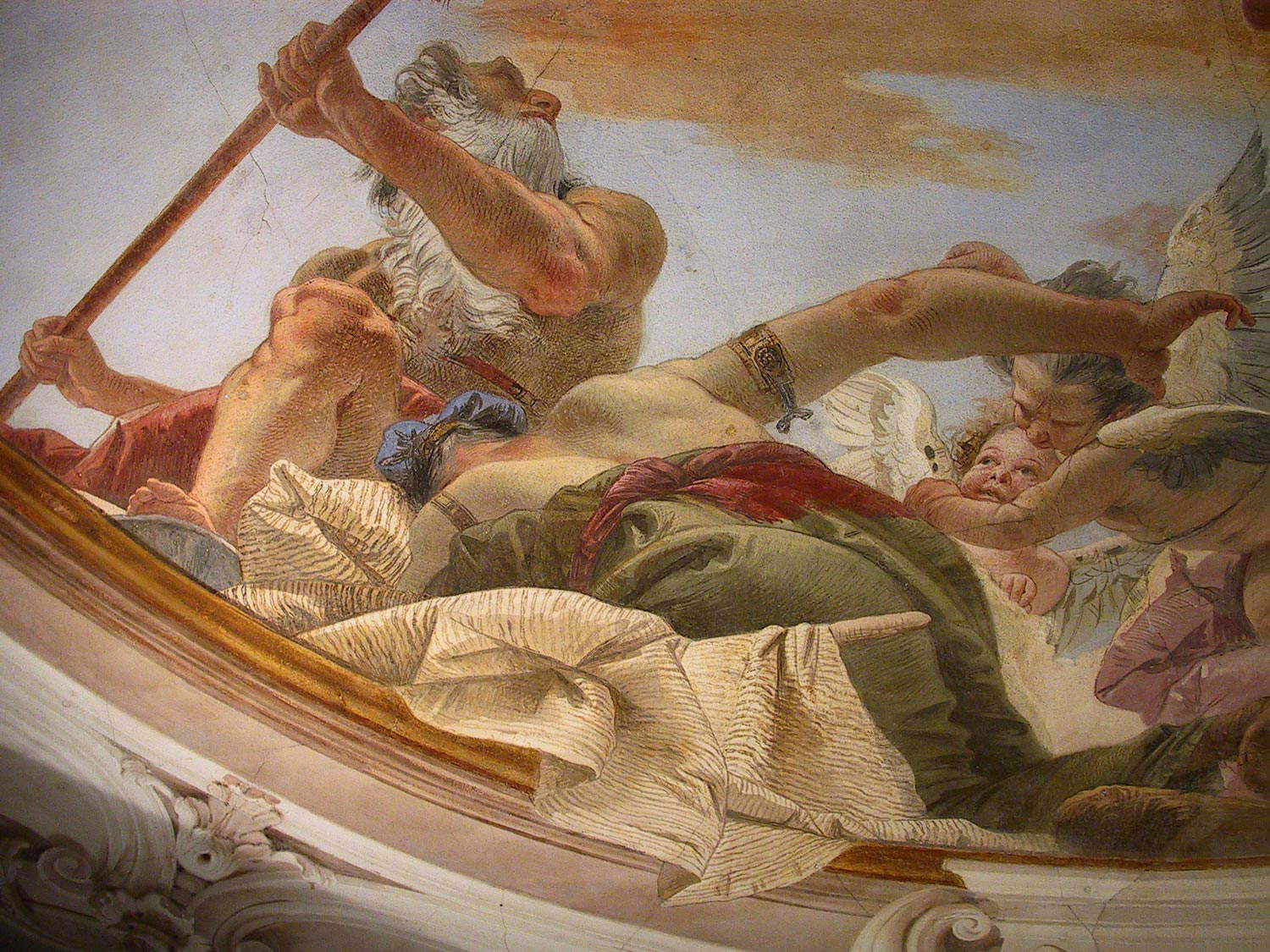

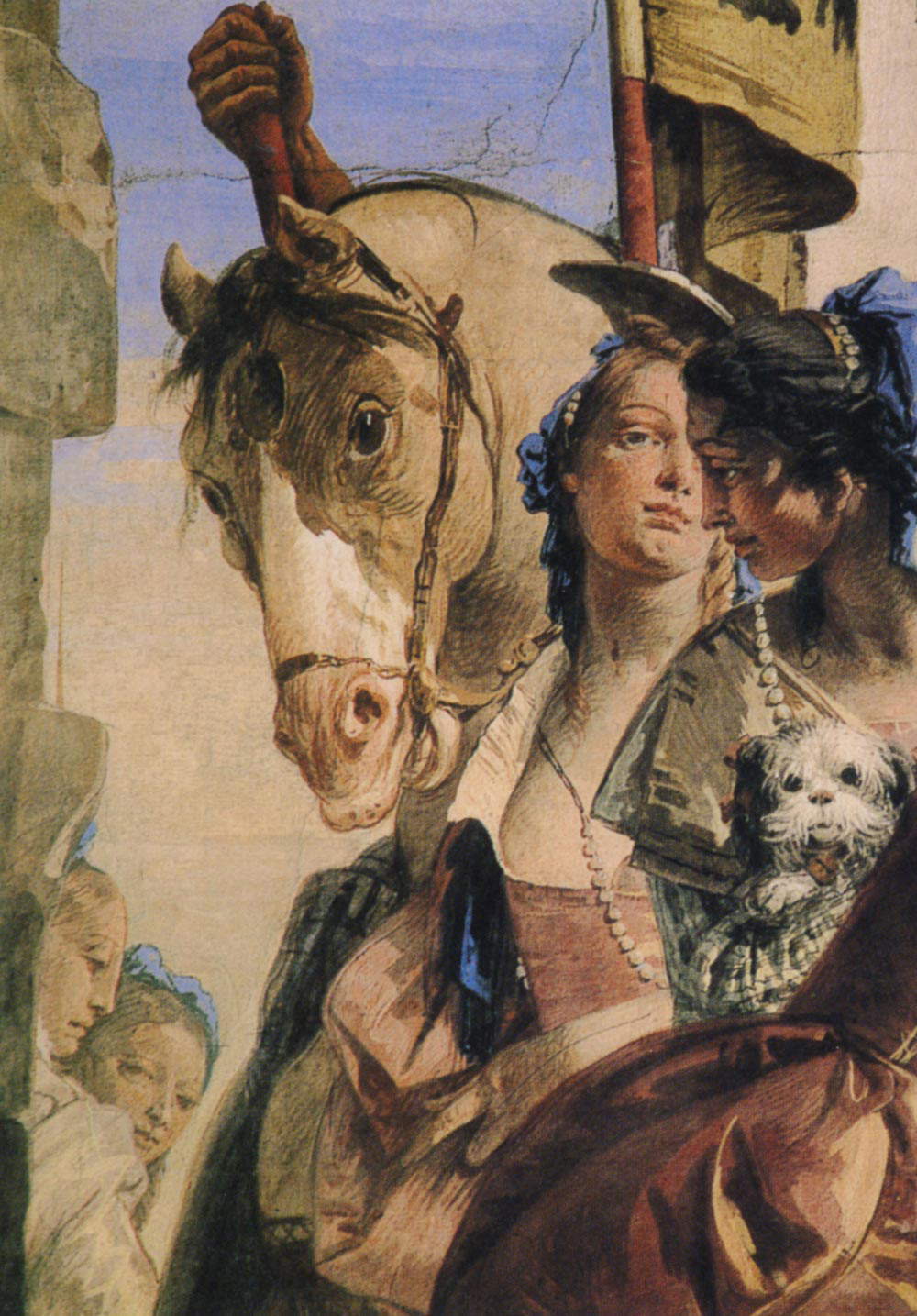

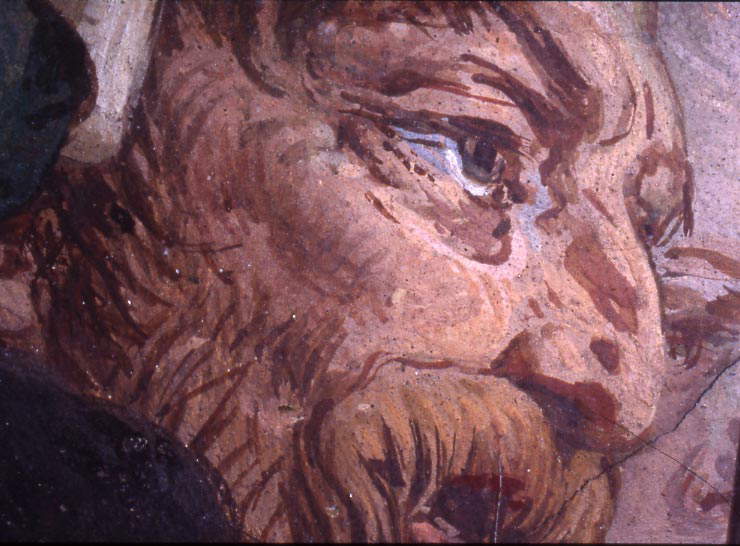

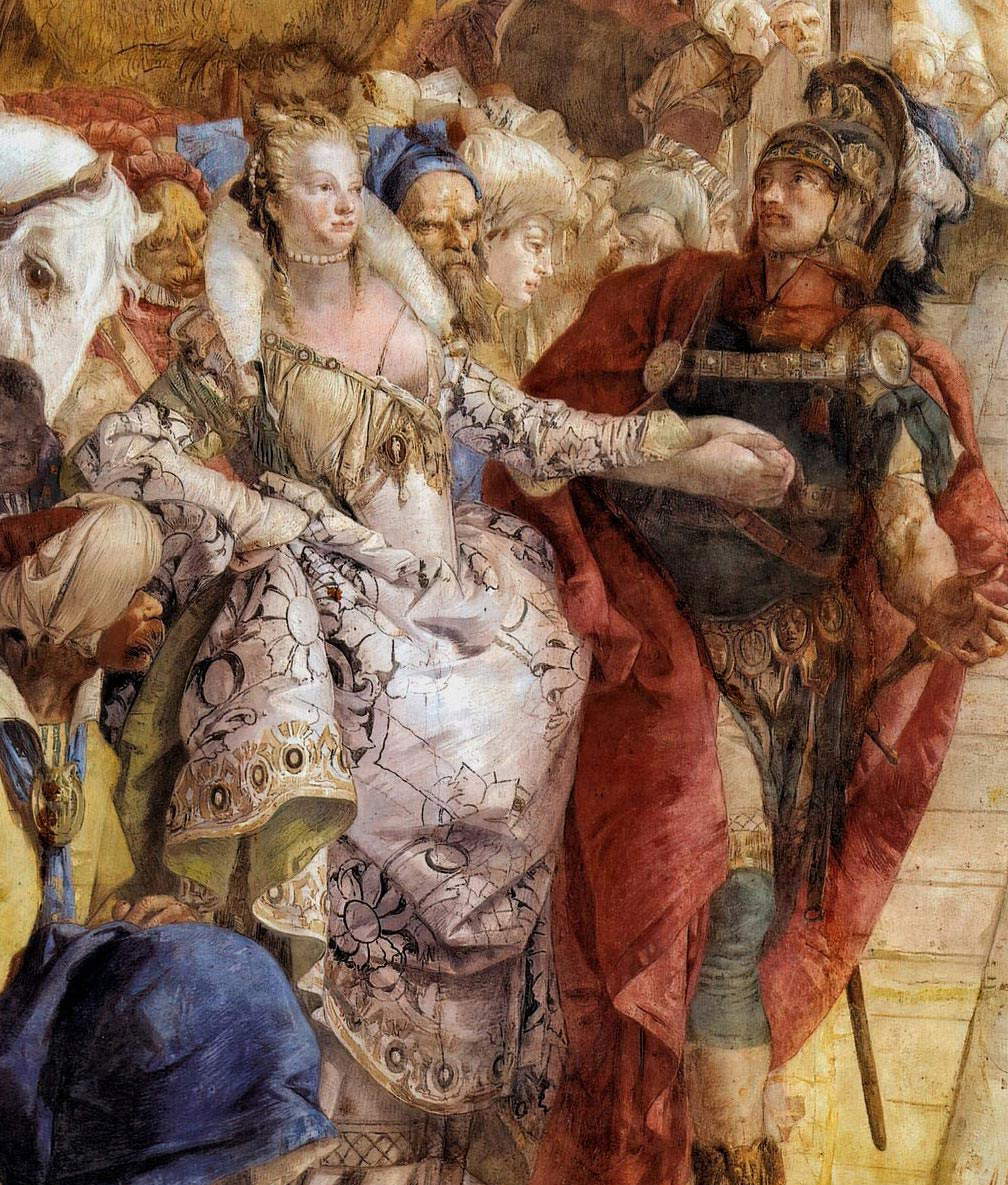

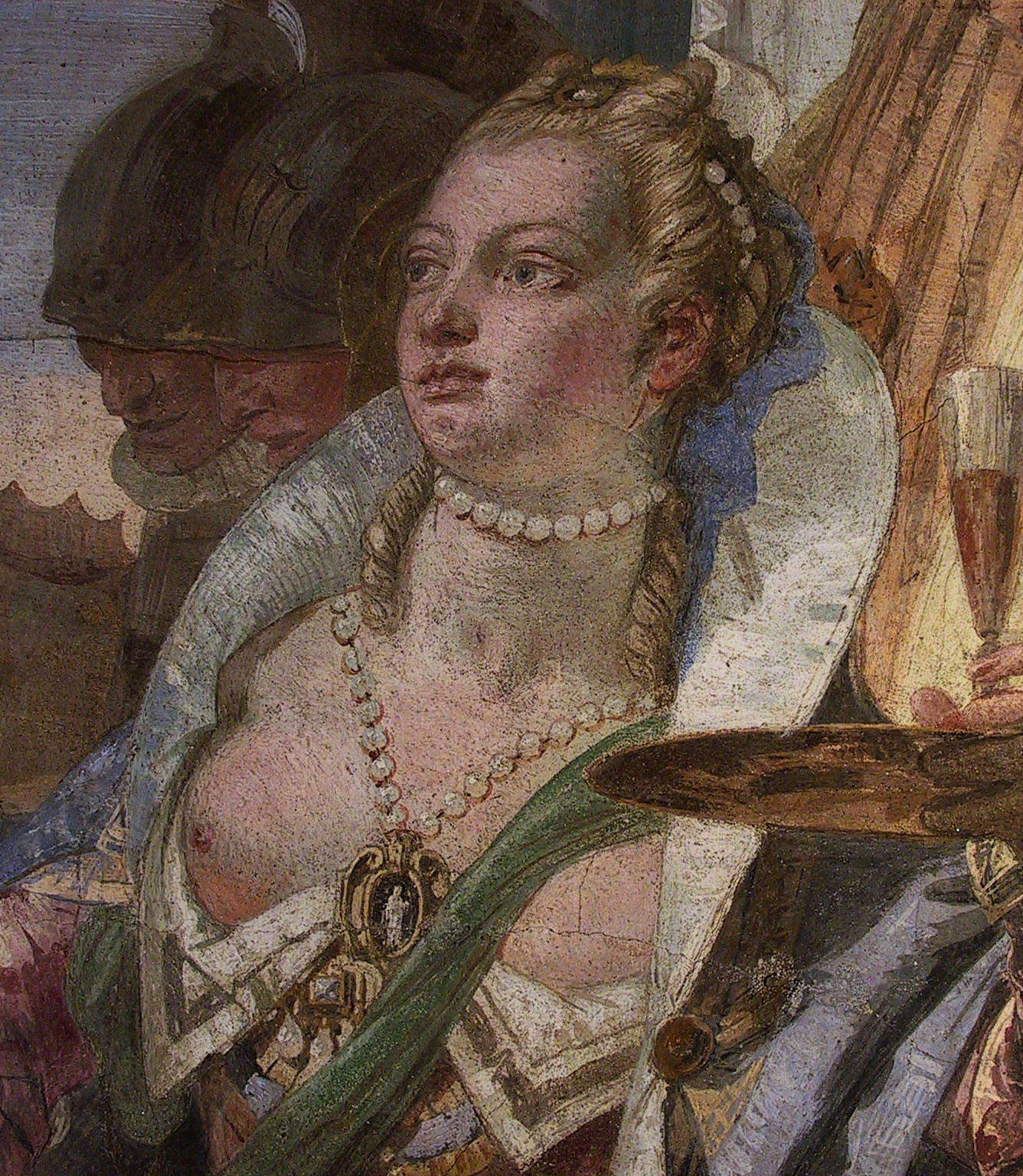

In recent days I am in Venice. Immediately I go to Palazzo Labia where for many years I have been trying in vain to get in to see the “Stories of Antony and Cleopatra” frescoed by Tiepolo in the Salone delle Feste between 1746 and 1747. Palazzo Labia became in 1964 the headquarters of Rai of Venice, which in that year bought it from Mexican billionaire Charles de Beistegui, the one of the legendary parties attended by the Aga Khan, Consuelo Crespi Christian Dior, Orson Welles, Cecil Beaton, Marella Agnelli and so on. I ask at the concierge desk if I can see the Tiepolo Hall. They reply that it is closed because the frescoes are being restored. I tell the speaker that for many years, when I come to Italy, I have been trying to see those frescoes but always I am told that they are under restoration. Response, “It is a restoration with a long time.” I then decide to ask my friend Bruno Zanardi, one of the best known Italian restorers who worked years ago at Palazzo Labia, for explanations. It was a very interesting interview because a totally unexpected and “very Italian” story came out. Unthinkable in my country, England.

AP. Professor Zanardi, Tiepolo’s fresco cycle in Palazzo Labia, Venice, has been closed to visitors for some 15 years. The same amount of time it took to restore Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. But the frescoes in the Labia Palace are ten times less in size. Why so much time for those restorations?

BZ. Because the Tiepolo frescoes are not under restoration.

They are not under restoration! But then why do they always tell me at Palazzo Labia that the Tiepolo Hall is “closed for restoration”?

Because of a decision made in 2008 by the then Superintendent of Venice, architect Codello. There had been detachments from the wall of Tiepolo’s frescoes in the Salone delle Feste. Rai wanted to finance the restoration of the entire decoration of the Salone. But the superintendent objected, despite the fact that the proposal was very beneficial for the Tiepolo frescoes, the city of Venice and the State Treasury. Not least because those detachments most likely had structural reasons. And that funding was also an opportunity to study the static tightness of the Palace with respect to high and low tides, currents of the Grand Canal, and so on.

But instead?

Instead, the superintendent had only the plaster detachments from the wall consolidated. After that she ordered that the Salone be closed to visits, leaving it as it was. That is, with in view the holes used to inject plaster consolidants on the wall. So that today those wonderful frescoes stand in a state of neglect.

An incredible story.

Incredible, but true. Do you think that there is a documentary running on the Internet in which it is said that those holes in the frescoes are the trace of nails driven into the wall to attach ropes on which to hang washed clothes by those who had occupied the Palace during World War II. Bale.

So you are saying that Tiepolo’s frescoes in Labia Palace have been closed to the public for 15 years for no reason. Invisible the masterpiece that immediately became famous throughout Europe. So much so that Reynolds and Fragonard left from England and France to go to Venice to copy parts of it to use as models for their works? That sounds crazy to me. But in all this time there were no protests?

There have been, partly because the superintendent who succeeded Codello, Dr. Carpani, also kept the frescoes closed to visitors. So much so that I myself, after an article came out a year ago in which a Venice newspaper denounced this scandalous affair, wrote a “certified letter” to the then Minister Franceschini, the Mayor of Venice and Dr. Carpani herself. But none of them answered me.

Is it possible that Italy’s artistic heritage is kept so sloppily?

The problem is that there are almost four thousand museums in Italy. Exactly 3,882, Istat writes. Of course, not all of them are the Uffizi, Capodimonte or Brera, but still they remain 3,882. Then there are 630 monuments and monumental complexes. And also there are 327 archaeological areas. Sometimes it is just the remains of a bridge or a few columns, but there are also the Imperial Forums, in Rome, and the whole of Pompeii. Not to mention the approximately 50,000 Italian churches under state protection. Churches that are almost all frescoed and with often very important paintings and sculptures inside. So you are faced with a huge problem that in fact no one knows how to solve.

But now in Venice there is the “Mose” that eliminates the high water that often flooded the city.

I wish that were the case. Because high water still floods the lowest part of the city, the part with the most monuments. The same one where St. Mark’s Basilica is located.

So the Mose project, costing 6.5 billion euros so far, is wrong?

This I cannot and will not say. What is true, however, is that the metal barriers of the Mose rise only when the tide reaches a height of more than one meter and ten centimeters. Below that threshold the water enters and floods St. Mark’s Basilica with its crypt, as well as, more generally, the churches, squares, streets, and stores of the entire St. Mark’s basin.

But to safeguard the sculptures, mosaics and stones then what is being done? Are the glass protections they put along St. Mark’s Basilica enough?

A couple of years ago a high-ranking Ministry official wrote in the newspapers that to save the Basilica from “high water” it only needs to be wrapped with “non-woven fabric.” The same remedy that my grandmother’s maid could point out. While in 2008, during a meeting of the Scientific Committee for the restoration of Tiepolo’s frescoes in Palazzo Labia, one of the experts claimed that the plaster detachments from the wall were due to the cold air from the air conditioning going up(sic: up!).

So?

So the glass protections are in technical line with what has just been said. Can you see Venice all edged with glass? And then who cleans and maintains those miles of glass since salt from seawater is corrosive? The superintendents who keep Palazzo Labia closed for no reason? Who protects the marbles with “fabric-non-woven”?

Now, however, there is talk of raising the entire basin of St. Mark’s to protect it from high water.

I read the news as well. All I can say is that, historically, engineering operations with those claims have always cost a lot of money and just as always, or almost always, their implementation has caused more or less serious structural damage to the raised buildings. And here the Basilica San Marco, the Doge’s Palace and so on are at stake. Anyway best wishes.

Proposed solutions to these problems for the new Minister of Cultural Heritage Gennaro Sangiuliano?

The solution has existed since 1976, but no minister has ever wanted to adopt it.

To wit.

To implement a policy of preventive and planned conservation of the artistic heritage in relation to the environment. The one defined in detail in the project formulated in years of research and studies conducted by the Central Institute for Restoration. An exemplary project that has so far been let fall by the wayside by ministers and ministries. Even though it is the only protection action that makes it possible to preserve the artistic and historical heritage of Italy and Italians in the quality that makes it unique in the world. Its infinite and bimillennial stratification in the territory.

So you are telling me that for half a century in Italy we have known in detail how to preserve Italy’s artistic heritage and no one is doing it?

That’s right. And the ad libitum closure of the Salon frescoed by Tiepolo in Palazzo Labia is one of the many proofs of that.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.