In recent years, the Uffizi has become a major player in the world of museums internationally, thanks in part to frequent, constant, pervasive, effective communication that has used a variety of tools and channels, from traditional media (newspapers, television, radio) to social media, even those never before explored by a museum. What are the dynamics that have led the Uffizi to invest time and resources in communication? What strategies does the Florence museum employ when communicating with its audience? What changes have you encountered? We talked about this with the head of the press office, journalist Tommaso Galligani. The interview is edited by Federico Giannini.

FG. Communication at the Uffizi travels through different channels: there is a press office, there is institutional communication, there are digital resources. I would start by asking you specifically who is in charge of what within the museum and what structures are dedicated to communication.

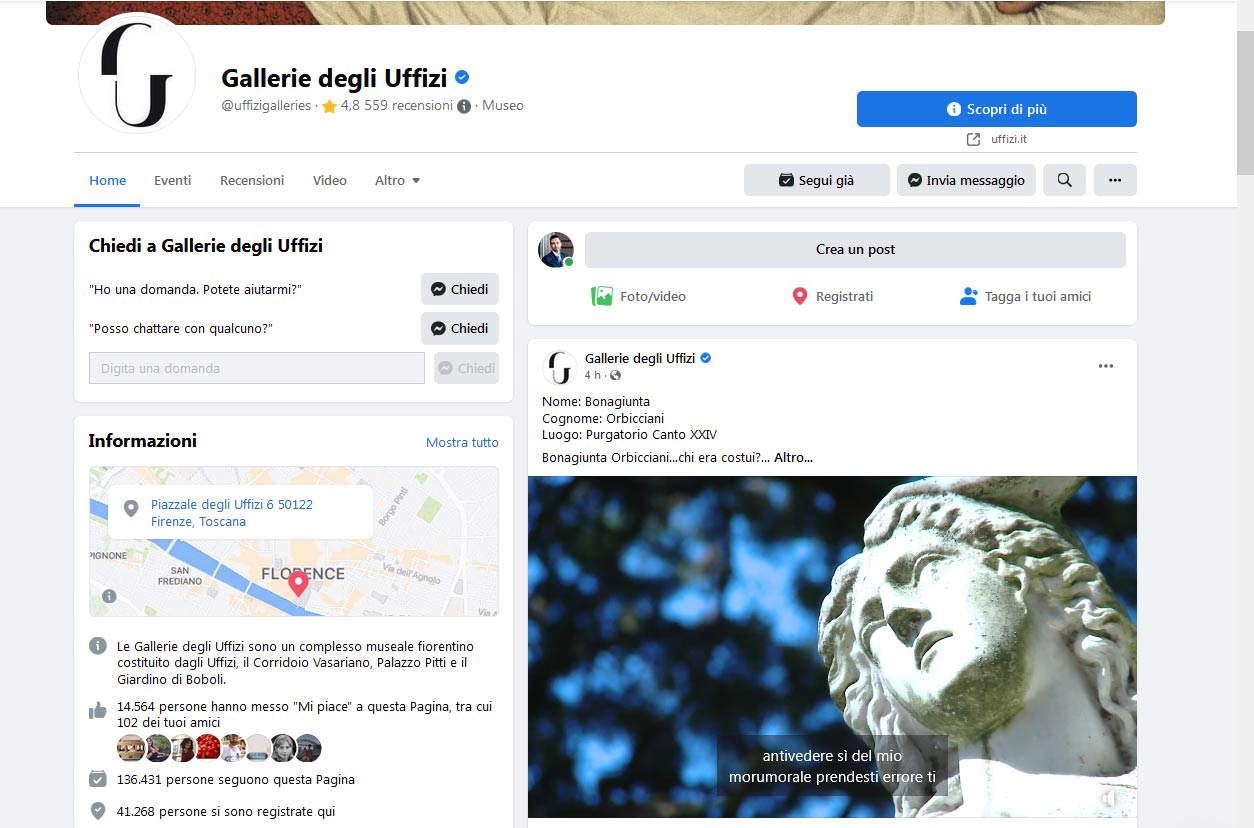

TG. On the one hand, we have the press office that takes care of all relations with traditional media (newspapers, television, radio, sites) and shared communication in the case of partnerships with other entities. Everything for the press and traditional media goes through my office. Then, next to the press office, we have the website and social media part, which are now the ordinary interface that the museum uses towards all potential types of users. Everyone can now relate to the Uffizi through a click, and the easiest way to do that, even before the site, is through one of the museum’s social platforms, each characterized by a different personality: Instagram, Twitter, the now traditional, generalist Facebook, and even the very famous TikTok, which has become our social and media star. This is our overall “deployment,” our armamentarium of communication with the outside world.

I would go into more detail on these topics starting precisely with the press office: never before has the Uffizi appeared as often as it has in recent years not only in newspapers and specialized magazines but also in generalist newspapers, not to mention, of course, the reports on television. I have not procured statistics, but I would empirically say that the Uffizi is the most talked about museum in Italy. This, of course, is not only because the Uffizi is still the largest and most visited museum in the country: behind this constant presence there is a well-defined strategy, and I would like if you could tell us something about how it is thought out and conducted...

First of all, it is necessary to immediately clear the field of a potential misunderstanding: no matter how willing, competent and good an expert or a communication specialist may consider themselves, we are still talking about the most important museum in Italy and one of the most famous museums in the world, which is why the Uffizi’s communication has its own ability to put itself forward on the crowded news market, in itself absolutely devastating and extremely powerful. Having said that, the basic strategy is very simple and can be summarized in a single sentence, which is then the reason why director Eike Schmidt recruited me in the now almost distant 2018: “the desire to tell the daily life of the museum.” Here, this is something that perhaps before, certainly also for reasons of system diversity, was done very little or not at all. Telling the day-to-day life of the museum has, in my opinion, served first and foremost to reveal to the public something it was unaware of: namely, that museums, as you at Finestre Sull’Arte know very well, are anything but dusty showcases full of sacred or pseudo-sacred objects, to be admired with bowed heads in suffering silence. On the contrary, they are true universes from which millions of stories, anecdotes, and beautiful or otherwise interesting information flow every day. From this inexhaustible cultural magma, and chronicle, one can derive a distillation that at times, as happens with the “proflux” of our communiqués, may perhaps prove to be excessively insistent, but certainly sketches a life and profile of the museum, in this case the Uffizi Galleries, as of a reality alive, dynamic, sympathetic (at least this is my perception from the inside, from the point of view of those who narrate it), and above all perfectly immersed in the flow of the world. So the exact opposite of those ivory towers that museums, in a way that far from corresponds to reality, have always seemed a bit like.

Your communication reaches both Italian and foreign audiences: many newspapers abroad have dedicated articles and reports to the Uffizi, and I would like to know what are the differences between the two audiences and consequently how do you deal with them when you have to get the content across?

I can say that the difference, again, is not that complex: let’s say that the audiences of foreign newspapers have to be more accompanied inside the news, inside the events and inside the stories we want to tell: abroad, although the Uffizi is world famous, our reality anyway is known much less than in Italy, and therefore strong news is needed, and offered with a greater simplicity than may be sufficient in packaging it for the Italian audience. In Italy, in some ways, the beauty and this cascade of art and cultural heritage in which the country is immersed are given as a known thing, so to talk to the Italian public requires codes of lesser simplicity, because the Italian public is used to interfacing with cultural heritage. With foreign audiences much more needs to be explained; this specificity is lacking. However, the most interesting aspect lies in the fact that there is also a much more mythical and dreamy approach to cultural heritage stories, also probably related to the greater scarcity abroad on this front. I am reminded of the amazement of some of my colleagues in the British press when I led them a few years ago to film a video report on the bathroom rooms of the Pitti Palace: they were literally dazzled by this discovery. Such a piece is a bit more difficult to pitch to an Italian audience, although then, somehow, we managed to do that as well.

A communications activity like yours I imagine must involve constant interaction not only between the press office and the director but also between those who do the communications and those who work on the collections, those who curate the exhibitions and so on.

Of course, it is a very close interaction: my job in this case is that of a translator. The curators who are in charge of the actual management of the holdings, who organize the exhibitions, who know all the secrets of what we hold, are art historians, and what they express and deal with, in order to reach the public in the most effective way, has to be somehow “translated” into press releases that inevitably simplify and sometimes maybe even approximate a little bit the precision and accuracy of certain concepts, certain details. But it is also an essential step so that the message of what you want to lead to the public gets through: the importance of an exhibition, what are the highlights, and the curiosities, which very often at the level of the press can even be more functional in attracting attention to what you are proposing.

After the Covid pandemic, but in any case these were activities that had already started before, the Uffizi has intensified its online presence: for example you broadcast all events (or most events: e.g. conferences, meetings, presentations, openings) on your platforms, you have a website that we can now consider a benchmark on how a museum website should be, not to mention the social presence which I would like to come back to in a moment, though. In the meantime, I would ask you what are the results that this intense activity has brought you, in terms, for example, of strengthening the museum’s image and therefore the public’s perception of the institution, as well as the growth of online and offline audiences, so if the online activity brings concrete and measurable benefits on physical attendance as well...

Undoubtedly yes: this kind of enhancement was done at a time when we had no other way to reach the public, because we were closed. And this was an opportunity to consolidate an instrumentarium that, now that we are totally reopened and our numbers are practically the same as pre-pandemic, we have been careful not to downsize, because it adds to the direct, physical, concrete relationship with the public, and it responds to different needs and methods of attractiveness. We, like all museums, have gained visitors and fans by proposing ourselves through social media and through the Internet, because the basic assumption, contrary to what some initially thought (i.e. that the museum that proposes viewing its treasures on the internet risks leaving at home all the people who could already see the Venus, the Spring or the Medusa from the couch stay there and do not go to admire them ’live’), is that these dynamics work exactly the opposite of what you might imagine: you see the Venus in pixels, perhaps even in very high definition, or a video that explains it in detail, or you read a card on the website, and yet then you are left wanting to see the original even more. It’s kind of like when someone listens to a band’s record that they particularly like: at that point it’s not that they don’t go to the concert anymore because they have the record; on the contrary, they go all the more precisely because they liked the record. It works exactly the same way here, and we after years of very intense web and social activity are back to pre-pandemic numbers in a flash, certainly in part due to good positioning on this kind of activity. Not only that: we have attracted a lot of young and very young people to the museum (and this is a great point of pride for us), who have become fascinated by these platforms that now, especially for them, represent the first way of relating to the outside world.

Moving on to talk about social, you are present everywhere: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok. What strategies do you apply to the different socials?

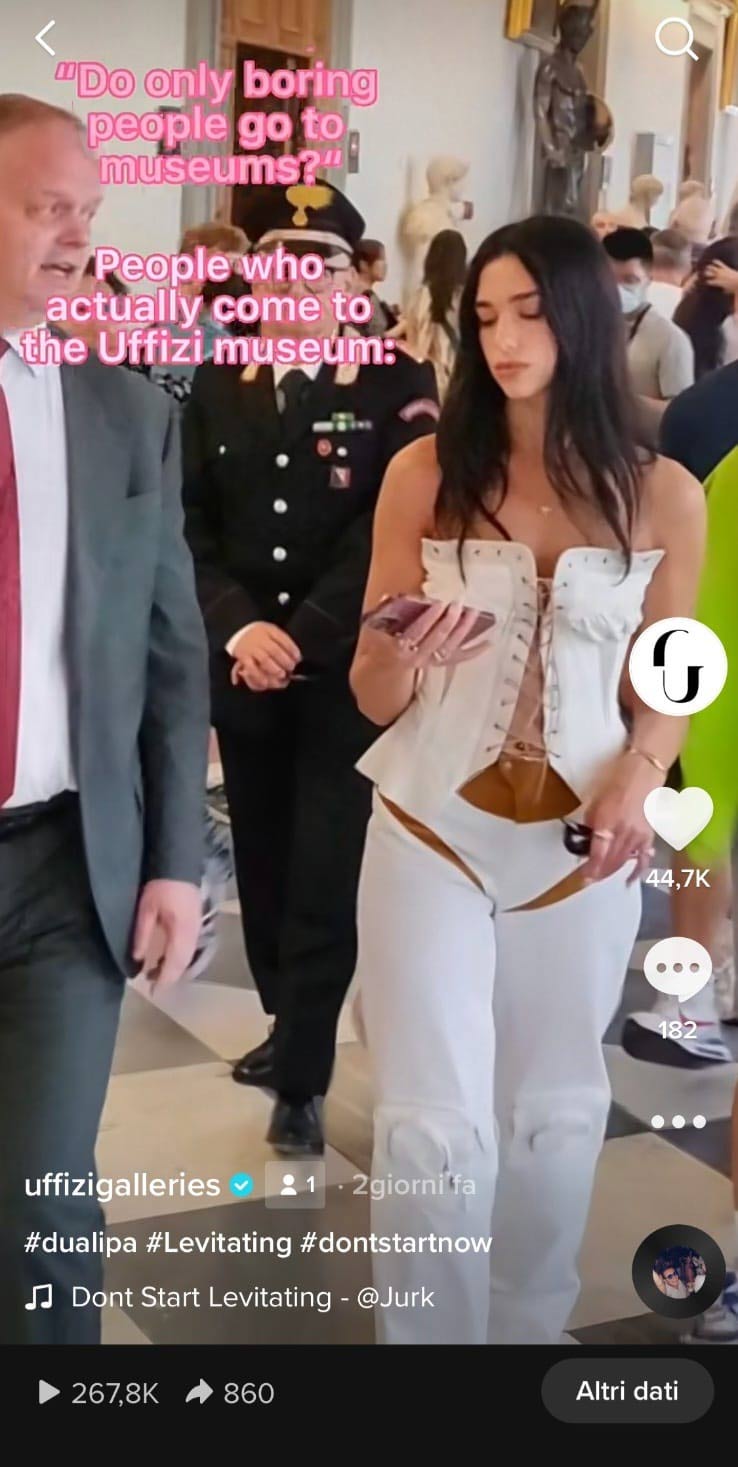

Each social has a distinct and particular personality. Instagram is consonant with the nature of the platform itself: more aesthetic, more graphic, based on image and loyalty of those who want to enjoy purely artistic content from our spaces (the Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti and Boboli Gardens). Then we have our generalist flagship, which is Facebook, which hosts a more heterogeneous type of content, and where you can find videos of various genres: we have series such as My Room where museum assistants illustrate spaces and works in our museums or individual works, the live broadcasts of the Uffizi on air series, that is, appointments where specialists tell paintings, sculptures and stories live and always answer questions from the public, then again the very successful series The Uffizi to Eat where we juxtapose some great chefs with works centered on culinary and gastronomic themes. We then do live coverage of press conferences and cultural events on Wednesday afternoons. Facebook is, in short, our basic ’broadcast container,’ the main one. Twitter is a bit of a mix between Facebook and Instagram, while on TikTok we decided (first museum in the world among the international ones in April 2020 to open a profile on this platform) to publish short ironic videos dedicated to our works. It was a gamble, an attempt consistent with our philosophy of telling the daily life of the museum, which also includes desacralizing a bit this aura of ’intangibility’ of the works, in order to initiate a more colloquial, fun and entertaining way of proposing them especially to the young and very young. It certainly seems that the experiment has worked: we recently surpassed one million likes on TikTok for our videos, and we are also thinking of new ways to expand the types of our content on this platform.

Uffizi

Uffizi Uffizi

Uffizi

You have also been criticized for certain choices you have made: I remember in particular the controversy stirred up by the presence of Chiara Ferragni, related both to her presence inside the museum and to the way you had communicated her, and those, on the other hand, about the way you had begun to communicate on TikTok. We specify, of course, that many, the majority, have instead welcomed these initiatives of yours, but there is a part of the environment, of the insiders, who have accused you of making a trivializing and sensationalistic communication. How do you respond to this criticism?

As we have been responding for two years now, because Chiara Ferragni’s visit was in July 2020 and that became the beach debate of that summer. Reminiscent of Berlinguer’s Sergio Forconi’s I Love You: “Pole an influencer allow himself to go to the museum?” Critics would have immediately said “no!” like Forconi in the film; instead, most people think, as we do, that an influencer can go to the museum and communicate it. The point is that the goal of a museum (and this is a personal opinion, but I think it can be shared) should be to open up to as many different audiences as possible: there is no need to be a snob, if anything the opposite. So why can’t an influencer be a way to tell the story of the museum? Why should we limit ourselves to already established forms and subjects that refer to or appeal to audiences who, by the way, already come to the museum? Let me explain myself better, leaving aside the Ferragni discourse: we have also communicated visits by actors, directors, sports personalities, for example with players of the Fiorentina women’s team; director Schmidt himself has been on sports television programs, always following the same logic, that is, trying to intercept audiences other than our usual ones, to try to intrigue them, to interest them in art, to convince them to drop by the museum, because then maybe they even get hooked (it happens often: it happened to me too, otherwise I wouldn’t be here). We did the same with rock, with the appeal to the participants of the big Florence Rocks event, inviting rockers who were playing as well as their audience to the museum. These ’experiments’ of crossing audiences work: it is also thanks to them that we had more young people, more people. Those who are interested in fashion, in fashion, in film, in music, in sports, why wouldn’t they want to be interested in art? And why not use its codes and language to better enter into communication with it? Not to do so regardless is snobbery, betraying the usual, well-known desire to shut oneself up in supposed ivory towers tied to elitist concepts of culture that no longer make sense: it is a wig-wearing, whitewashed sepulchre mentality that we here at the Uffizi try strenuously to combat.

If, however, between rock music, fashion and art there is nevertheless a vivid contiguity, it is more difficult to find, for example, connections between sports and art, and the audience of sports as a result might seem much more distant. What is the mechanism that leads a sports fan to cross the threshold of the Uffizi, and how does your experience translate? What feedback do you get from these audiences who may never before have set foot in the Uffizi or even in a museum?

There are no answers in my pocket. What there has to be, however, is a willingness to put yourself forward to these different audiences, going to meet their language, their perception and their interests. Fortunately for us, it is a kind of passepartout, because it has all kinds of interpretive codes and can therefore dialogue effectively with all kinds of sectors. Because art is all-encompassing, it touches on all subjects: at the Uffizi, for example, we have works, especially in the field of Roman sculpture, that deal with sporting themes, that recall the bodily plasticity of sport, or evoke its symbols. The suggestions that art can offer toward audiences interested in other things, even seemingly distant themes, is endless. Moreover, and I understand that this may seem a trivial consideration, it is a fact that beauty has in itself the potential to attract anyone. Beauty itself is endowed with attractive capacities in every field; therefore, a field such as art, which has beauty as its raison d’être, holds the keys to dialogue with everyone, and this is what we try to do.

There was, however, a watershed in the way the Uffizi interacts with the public, and that watershed was the 2014 reform with the subsequent arrival of Eike Schmidt as director, which in this sense caused a small revolution especially on digital: in particular, the Uffizi was almost completely absent from social media and had a website that was not very up-to-date, not very modern, not very functional. What work had to be done to transform the Uffizi into a museum at the forefront of communication?

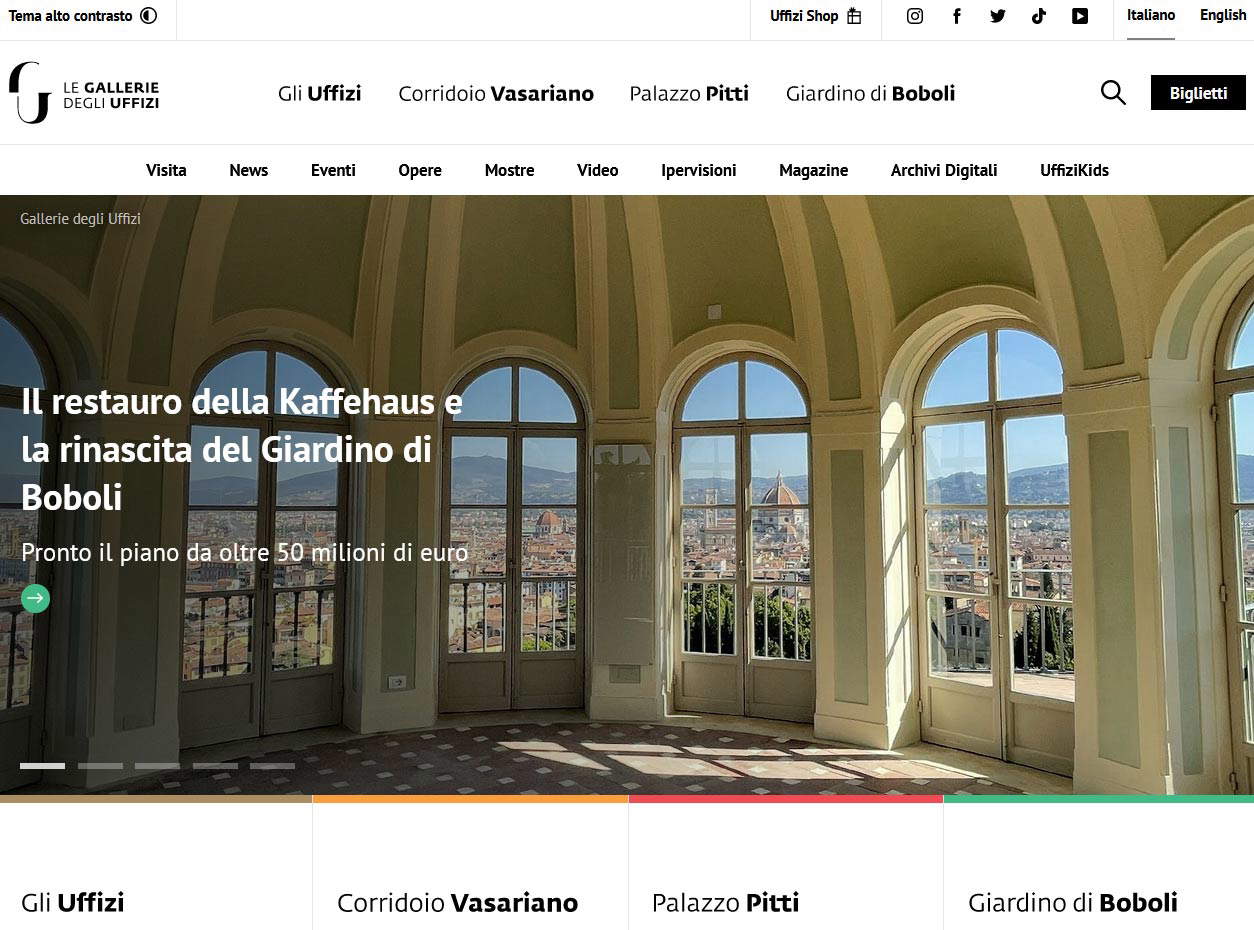

For this, Eike Schmidt must be given credit, and I say this without fear of flattery. In this area the Galleries stood at practically zero, and he from zero created more or less everything: he set up out of nothing (there was none, and understandably so, because, although it seems strange to say it, seven years ago was practically another era) an ad hoc department for digital strategies, the Uffizi had no website (there was a page on the Polo Museale Fiorentino website, with a primitive and totally ineffective positioning), there was no logo, there was no brand. In short, there was practically nothing. The museum’s communication as we see it now was a way of positioning itself built up over a few years, and this happened at Schmidt’s behest. However, this should not be read as a criticism of the past: it was simply another world before. The cultural heritage reform of 2014, by making major museums autonomous, made them protagonists in a way they had never been before: the system became partly decentralized and these cultural venues found themselves to be like real rock stars, perpetually in the spotlight. Unlike before, with a much more hierarchical, centralized, and centralized system in Rome, the great museums found themselves having to stand on their own two feet, doing a lot of things on their own and even communicating on their own: this change was necessitated by the change in management and perspective introduced by the reform, which, in Florence, transformed a unified reality such as that of the Polo Museale Fiorentino (which brought together more than thirty museums) into a much more fragmented and diffuse reality, in which each of the large museums present (Uffizi, but also Galleria dell’Accademia and Bargello) had to learn very quickly how to go it alone. To this must obviously be added the impetuous change that in recent years an increasingly digital and virtual society has also imposed on museums: equipping the museum with tools that would make it capable of keeping up with the times had become an obligation that could no longer be postponed. This explains the premise of the titanic work of creating the ’digital’ identity of the Uffizi: an identity that is strong, yet at the same time multifaceted, multifaceted, but which until a few years ago did not even exist. Today it seems taken for granted that a great museum like the Galleries has an efficient website, www.uffizi.it (where you can find information, the magazine, the in-depth scientific articles of Imagines magazine, the works, videos, etc.): the truth is that all this exists since 2017, before there was not. Likewise, also since 2017, the Uffizi has had a logo that in a short time has made them even more visible and recognizable on the web and beyond: sure, the name needs no introduction in the world, but a logo that defines you in a way as a unique and exclusive identity, helping to position you in the complicated and often bad universe-jungle of the internet has helped a lot: proof is that we even won the prestigious ’Compasso d’oro’ award for communication design.

Today what profile should a person working in the communication sector of a museum have?

The very first double requirement, I say this at the risk of sounding extremely banal, is the fantastic curiosity-humility combo. I think being a journalist has helped me tremendously in moving in this strange world: on the one hand by exercising all the curiosity I can to try to understand as quickly as possible the countless rules, dynamics and stories one comes across wandering around the cosmos of very different microcosms that is a museum; on the other, demonstrating the humility necessary to realize that in such a place there is indeed a great deal to learn, even more to look at and listen to, and absolutely nothing to take for granted. Then there is naiveté, understood in the sense of amazement at the stories: it is fundamental, because what a communicator has to do in a museum is precisely to tell its stories, facts, anecdotes, numbers, curiosities, and to do it at its best, with emotional participation, one has to have a soul, so to speak, ’easy to wonder’ and ready to be passionate even about small events, which then, at the Uffizi, are never small. Let me give an example: last year a swarm of wild bees established itself in the Boboli Gardens: these ingenious insects had found no one knows how to build their hive in the belly of a centuries-old wall and then set out to scamper (peacefully, without any disturbance to visitors, in the typical style of bees) among the flowers of the Medici lemon house. I learned almost by accident about this fortuitous event and instantly fell in love. It seemed to me an incredible story, thinking also of the importance of the environmental issue today: the bees had chosen Boboli, the green lung in the heart of Florence, as their home. I pitched it to the press and it went very well: the media became very happy to share this small but significant anecdote that happened at the Uffizi Galleries. Finally, you have to learn how to write well, because writing is and always will be the basis of all forms of communication (but that was said by Umberto Eco and Bertrand Russell, it’s not like I’m saying it), and you obviously need predisposition and interest in cultural issues. Add up all these characteristics, and you have the requirements to be good museum communicators.

In your opinion, how much more work needs to be done in the world of Italian museums to arrive at adequate communication standards, taking into account that there are differences between large and small museums, and that there are still important gaps between central and peripheral museums, as well as between north and south?

I don’t want to make a category argument, but, in my opinion, it would be really important for museums to have press offices, in-house and trained exclusively by journalists: and just as there is a law on this for public administrations, the same should apply to museums. The journalist brings an approach to storytelling that has the characteristic of being able to easily insert the museum into the flow of the public narrative: of the host city, the country, even the world, if the museum has the size to get there. To perform this function best, the journalist needs to be able to tell the story of the museum from the inside, being in it every day, not working from the outside, in outside companies, on time assignments, or perhaps on call. This dual aspect, working from the inside with the right skills, is not well present in a great many museums and can often translate into less ability to communicate or understand the specific dynamics of the world of information: let us remember that like all professional fields (architecture, engineering, law, art history itself) the world of information also has its own particular dynamics and logics, and it takes a professional to understand them, read them, decipher them, and use them properly. Museums, but I would say cultural institutions in general, live on communication more than any other type of subject: an exhibition must be communicated well, otherwise people will not go there; the acquisition of a work must be communicated well, otherwise people will never know that that work has been acquired by the museum; the opening of new rooms must be communicated well, otherwise people will never learn that there are new spaces. And so let’s reiterate: there is no subject more dependent on the need to communicate itself than the cultural subject, and, specifically, the museum.

To conclude, there has been a lot of talk lately about a lot of innovation on digital, for example, there are museums that offer visitors the possibility of choosing personalized tour routes from the site, there are virtual tours, without then getting into the NFT discourse: in short, it is a world that is evolving. How will the Uffizi continue to enhance its activities? Are there any projects at the level of communication that you are going to build up from here soon?

Communication at the moment is going very well, and this is also because we always have some new project simmering in the pot. However, the first and best rule of communication is to know how to communicate at the right time-when we are ready to do it, you will be the first to know...

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.