The printed editions of Cennino Cennini's Book of Art: interview with Giovanni Mazzaferro

We open 2014 on our website with an interview with Giovanni Mazzaferro, head of the Mazzaferro Library in Bologna, a collection specializing in art literature, consisting of some 1,800 volumes. Giovanni Mazzaferro, who holds a degree in Economic History from the Faculty of Economics and Business at the University of Bologna, has more than 20 years’ experience in the publishing industry, having worked at a famous Bolognese school publishing house, and inherited a passion for art literature from his father Luciano Mazzaferro, who was an art critic for Il Resto del Carlino and started the library’s collection of volumes in 1950.

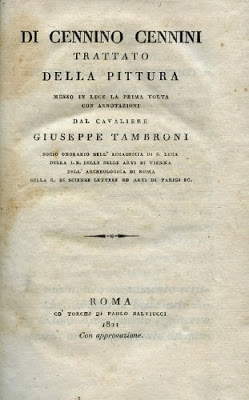

Recently, Giovanni has been involved in the census of printed editions of one of the fundamental treatises on art as well as among the greatest examples of art literature ever, Cennino Cennini’s Book of Art. Thirty-three editions (which become 54 if reprints are counted) were surveyed, making the Book of Art the most widely circulated text of art literature in the world after Giorgio Vasari’s celebrated Lives. Giovanni Mazzaferro’s work is available on his blog Art Literature, which is dedicated to reviews of the precious books found in the Mazzaferro Library.

As anticipated, we contacted Giovanni who gave us an interview about the work he conducted. We therefore thank him for his availability and wish our visitors good reading!

The Book of Art is the most famous Italian treatise on artistic techniques. Written by Cennino Cennini, a disciple of Agnolo Gaddi, it is a book that stands as a direct heir to the medieval artistic cookbooks and a precursor to the first artistic treatises of Italian Humanism (first and foremost Leon Battista Alberti’s De pictura). Compared to the earlier artistic cookbooks Cennino detaches himself, meanwhile, because he claims authorship of the work (the importance of the painter’s role as a practitioner of a liberal art begins to emerge) and because of its organic nature. From a theoretical point of view, Cennino is famous for a statement on Giotto (who remuted larte del dipignere di grecho in Latin and reduced it to the modern) that would later become a fixed point in Italian historiography, from Vasari onward (Vasari knows of Cennino’s book, but it is not known whether he read it). Nevertheless, the treatise still exerts a particular fascination for practical aspects, precisely because it illustrates the techniques of fresco and tempera in use in the late fourteenth century. And for that very reason it is also of particular interest to restorers and all those faced with problems of conserving pre-existing works.

You carried out the printed census of Art Book editions: how did you conduct your work?

On the one hand by starting from the bibliographies in the editions that I had a chance to consult. In this way I arrived at about 20 occurrences. Then used the potentials of the net and especially Google’s advanced search (limited geographic area searches, single language searches). I was not familiar with, and found Google NGram Viewer particularly useful. In essence, from a database of five million books it is possible to search by entering certain terms (in my case Cennino Cennini) from 1800 onwards and by individual languages (the most important ones). Looking at the years around which the peaks were clustered, I searched for printed editions. The first Spanish edition of 1947 (actually printed in Argentina) was found in this way. Finally by taking on board the indications of other individuals who knew of editions I had not found, and which I of course cited in the text.

Of the editions you surveyed, is there one in particular that you would recommend to those who want to learn more about the Book of Art and the figure of Cennino Cennini?

Of the historical editions I would certainly recommend the MIlanesi edition (from 1859) because it is impeccable, both as a translation and as apparatus and archival research. Among the more recent ones, obviously the Frezzato edition of 2003, which marks an unquestionable step forward compared to the previous ones, especially because it addresses the study of the work from different but complementary profiles (historical, linguistic, technical and whatever aspects)

Have you had a chance to present your work to the community of art historians? And how will art historians benefit from it?

I have not made official presentations, but I have written to art historians who I knew were interested in Cennino. My work is actually somewhere between art history and bibliographical study. I have the limpression that not all art historians had a perception of how strong Cennino’s influence was historically in the world. It is not for me to say whether gaining this awareness can be a stimulus to further studies on the artist from Colle Val dElsa. I hope so.

As is evident from the presentation on your site, your work is a “work in progress.” How do you plan to complete or improve it?

When I published it there were 33 identified editions; today there are 40. It is my attention to add all the news that will be acquired in the future. In addition, I would like to be able to acquire as much information as possible about editions about which I know little or nothing and about which I have often speculated: why a Polish edition in Florence in 1933 and one in Warsaw in 1934? who was Nakamura Tsune, who began a Japanese translation before 1924? does the Norwegian edition of 1942 have anything to do with the Oslo degenerate art exhibition of that same year? The dream would be that scholars (or amateurs) around the world would translate the individual prefaces into English and that there could be a virtual place to find them.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.