When we begin to grow up we are often instructed to draw one straight line and slavishly follow it containing any smears, second thoughts or deviations. We are taught that we can be one thing and one thing only if we plan to take part in the world of the excellent, because those who change fail and those who refuse to box themselves within clear-cut, binding boundaries are only dreamers. Photographer Giovanna Dal Magro, born and living in Milan where she began working in the 1970s, chose, with precise wit and great tenacity, to ignore and cross all these frightening and gray boundaries, creating something to her very personal measure, a life for herself and that resembled her as much as possible. And she tells her story in this interview.

FAG. How did you start working as a photographer and journalist and what made you approach photography after experimenting with painting?

GDM. After attending the Academy of Painting at Castello Sforzesco in Milan, I had many ideas for the future, but I always sought excellence and saw my pictorial works as extremely banal, plus I had become a mother and decided to leave this path very naturally. After about two years, on a very simple day, I went to visit a friend, the photographer and graphic designer Aurelia Raffo, in her darkroom and in a fleeting moment I saw the photograph rise from the acid. I was thunderstruck, I was thunderstruck, and just as the image had revealed itself from the acid, so did I re-emerge and from that very day photography became my trusted companion in life. I began my training in a photographic studio starting with printing and loved it so much that, very often, I would come home to put my son to sleep and rush back to the studio to work incessantly and with ardent passion, until two in the morning. But printmaking and photography are two very different arts, and I approached my real, very great passion on tiptoe, studying a lot and always helped by my friends at the Academy, attending every event and especially browsing through all the exhibitions in town. I was hungry and that was how I learned the art of photography, trapping in my lens everything I could without ever specializing in anything, despite the fact that my friends suggested that I should choose one theme and follow that for the rest of my life. But I am a person who never eats the same dish as the day before and always changes scents, so how could I fossilize myself within one theme to follow religiously all my life? Impossible for me, it’s not in my nature, but I think the hallmark of my art is really freedom. I am not a photographer, it’s five photographers in one lens. I love to change and experiment with new ways all the time, and that’s why, around the 1980s, together with the artist Rosanna Veronesi I decided to approach conceptual art and we were able to make a lot of retrospectives. It was a very special time when we created a lot of installations, we wanted to be the female Gilbert & George and we had a lot of fun until the end of the project.

What were the most significant moments for you in your reportages on five continents?

My favorite places were those that offered me the opportunity to discover and learn about the history of great cultures. One of my first trips was to discover Mexico, when there was still no mass tourism and you could go up to Chichén Itzá. Here I saw the sculpture of Chac-Mool, a male human figure lying on his back with his knees bent, his feet anchored on the floor and his head turned at a right angle, holding in his hands a kind of tray in which the hearts and blood of the sacrificed were believed to be placed, and it seemed to me that I was having visions and I am convinced to this day that I saw that same liquid in his stone hands. Another place that enraptured me was Rajasthan and every time I saw the goddess Kali, as well as other statues of Hindu deities, I daydreamed so much that I could not distinguish reality from fantasy. The same thing happened in the Venezuelan Amazon, where I desperately wanted to photograph the Ye’Kuana ethnic group and had the great good fortune to run into the indigenist Albert Valdez, who helped my husband and me rent a small plane to enter that community. The trip in that tiny plane was terrible and my insides contracted the whole time, but eventually we touched down and discovered a breathtaking sight. Men were returning from the “great hunting festival,” a very rare event with no exact dates that even our new ethnologist friend had never been able to see. It was a unique spectacle. The men were helping themselves to special solar panels to hunt, and under all those lights I was enchanted and took an endless amount of photographs that were later exhibited at Lanfranco Colombo’s Milan Diaphragm Gallery. They liked them very much and, as a result, many articles also came out, which I proudly sent immediately to Albert Valdez, who got us passes to climb Autana, the sacred mountain of the Indians, where no white person had ever been because they had not earned it. This trip was also tremendous, filled with hiccups, sunken boats, contracted illnesses, unspeakable fatigue and a consuming fear of dying, but it was worth it. To get to Monte Sacro we had to ask permission to continue from every village chief we encountered on our way, and once we reached it, it was a spectacular experience lived intensely and on the ground.

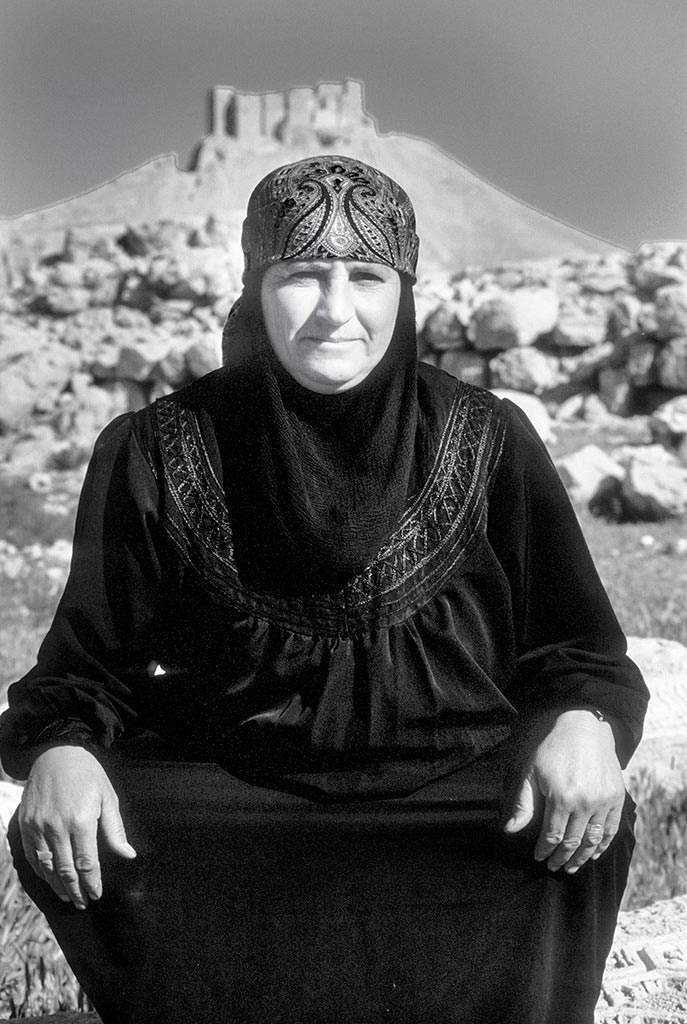

Giovanna Dal Magro

Giovanna Dal Magro Giovanna Dal Magro,

Giovanna Dal Magro, Giovanna Dal Magro,

Giovanna Dal Magro, Giovanna Dal Magro

Giovanna Dal Magro

How did you meet and portray such figures as Marina Abramović, John Cage, Andy Warhol, Dario Fo and others?

They were things that simply happened in a city like Milan that always offered countless chances and opportunities. A young Marina Abramović came to Luciano Inga Pin’s Diagramma Gallery in 1974 to present Rhythm 4, and I, of course, was there. For the occasion, the audience had to stay outside and could see the performance from special televisions, while I managed to squeeze into a corner of the room to portray her at her best. Marina knelt, completely naked, in front of a large industrial fan with the purpose of jamming as much air as possible into her lungs until she collapsed. It was a very hard physical and psychological test for which no one was prepared, no one expected. From that day on we immediately became friends and I used to visit her and Ulay very often in the countryside where they lived and, right there, I took many photographs of them in the company of the little dog and the truck. I met Dario Fo in a very similar way, simply by going to the theater at the Palazzina Liberty in Milan. The meeting with Vittorio Sgarbi, on the other hand, was very peculiar and funny, it could not have been otherwise. I was in Venice, hosted by an art historian friend who told a few acquaintances that I was right in her house and, one day, while I was sleeping I was jolted awake by a not-yet-famous Vittorio Sgarbi who shook me laughing and saying that he wanted pictures. Terrified and groggy from sleep I shouted at him, “Who are you? I mean, what do you want?” but once I calmed down we threw it into laughter and I took all the pictures.

What are the most precious memories they left you with and which character did you find most interesting and why?

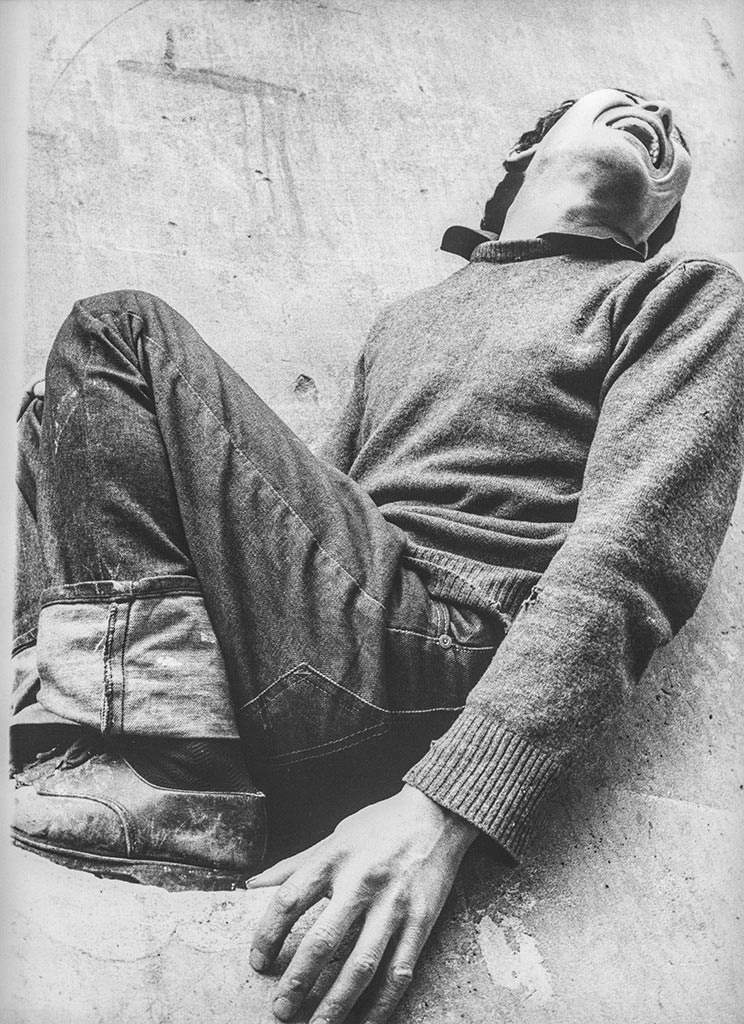

I always felt very close to the writers, they were funny souls, often out of the box and extremely intelligent. In Moscow I photographed Jurij M. Naghibin, an incredible character, very well known and extremely humble, in Peru I immortalized Manuel Scorza who was one of the first Peruvian writers published by Feltrinelli. Another man I found particularly interesting was Aldo Busi, who possessed a stratospheric intelligence, beyond human comprehension, and because of that, photographing him could be an almost impossible job. He hated to stand still, rigidly posed, waiting for the shot, and he was always apostrophizing me to film him talking and moving, but I did not work that way and took unsatisfactory pictures, and just as I was thinking about the gigantic failure, I realized I had to change my approach: I had to be able to fool him somehow, trap him. I made up the fact that I had finished the job, pretended to put all my equipment away, and as soon as I put the camera down, he lay serenely on the couch mouthing something that sounded like an exhausted “finally.” It was the perfect shot. Two photos, two only, just the ones that were missing to finish the roll. I hastily warned him and stopped that fleeting, relaxed moment forever. It was simply him, captured by my camera, and Aldo, those two photos alone, liked them so much that he began to introduce me as the one “who managed to bare me inside as well.”

There definitely has to be an innate talent and a lot of work to be able to understand people, read them and put them at ease to stop forever that characteristic that you saw in them and I also think that this is the great strength given by the lack of clear boundaries in your work.

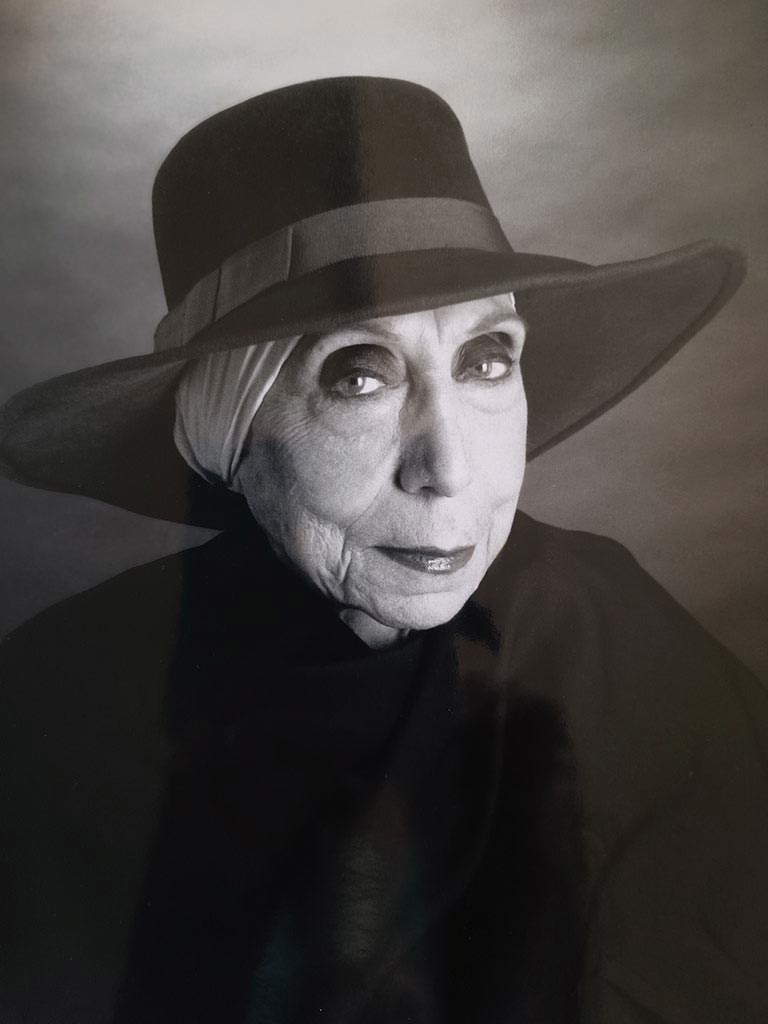

Exactly, some things are innate, inherent in us, and only through hard work are they strengthened and take more solid forms. While I have never chosen one rigid thematic path to follow, I have always liked portraits, especially because I started there and they will always have a very strong emotional charge for me. I was extremely insecure as a girl, and among my first assignments was to photograph the art critic Gillo Dorfles. I showed up trembling, with a multitude of catastrophic thoughts cluttering my mind and with the very firm conviction that if I made the smallest mistake, my career would be over forever, nipping suicide in the bud. I was the picture of unrest, and the malaise only increased, sinking its claws into my stomach when he received me in his studio with the darkest face I had ever seen: he was already angry that no one could take pictures of him that would satisfy him. He had opened a small drawer and was waving and tossing photographs that I thought were wonderful. I felt I was finished before I even started, but I had to take courage and think quickly. I decided, in a moment of fleeting lucidity, to take him outside to admire his beloved Art Nouveau buildings and he was extremely enthusiastic. He settled the Borsalino on his head and we were ready to go out and while he was mesmerized by his own story, I hid and began to portray him. He was so thrilled with the shots that, not only did he mention me in an article in Corriere della Sera where he talked about the four most interesting Italian photographers, but he also started sending me chocolates at home and, once, left a note that said “thank you for trying to aestheticize me.” From that moment I understood that photography, for me, was as natural as breathing, but above all that I always had to be the one to get the better of the most difficult characters, especially when they gave me little credit because of my young age. Another experience, similar and opposite at the same time, happened in Manchester to photograph the world’s largest arms dealer who looked like a loving and extremely smiling old grandfather. We were in an old factory flat with weapons of all kinds, where every wall exuded death and despair, and I hated every moment locked within those walls with a man who did nothing but laugh and think about the coming Christmas. What does destruction possess that is funny? I didn’t understand it. I was tired and furious, and I was so angry at the situation that I made him grip the machine gun tightly in his hands and immediately ordered him to stop laughing. He took offense and the picture came out perfect.

While studying your work I fell in love with the photograph of Kengiro Azuma sitting in one of your sculptures, can you tell me how you met and specifically the story behind this shot?

Azuma was an incredible character, every time he saw me he laughed heartily and possessed the affection typically associated with a Neapolitan. I met the sculptor thanks to a Japanese photographer I had hosted for a while in my old studio in Via Bramante, and we became friends at first sight, we would stay talking for hours telling each other everything. We saw each other, for the last time, shortly before his death to celebrate his 90th birthday and I remember him with eyes filled with the same joy and enthusiasm as when he was young. It was a sincere and wonderful friendship.

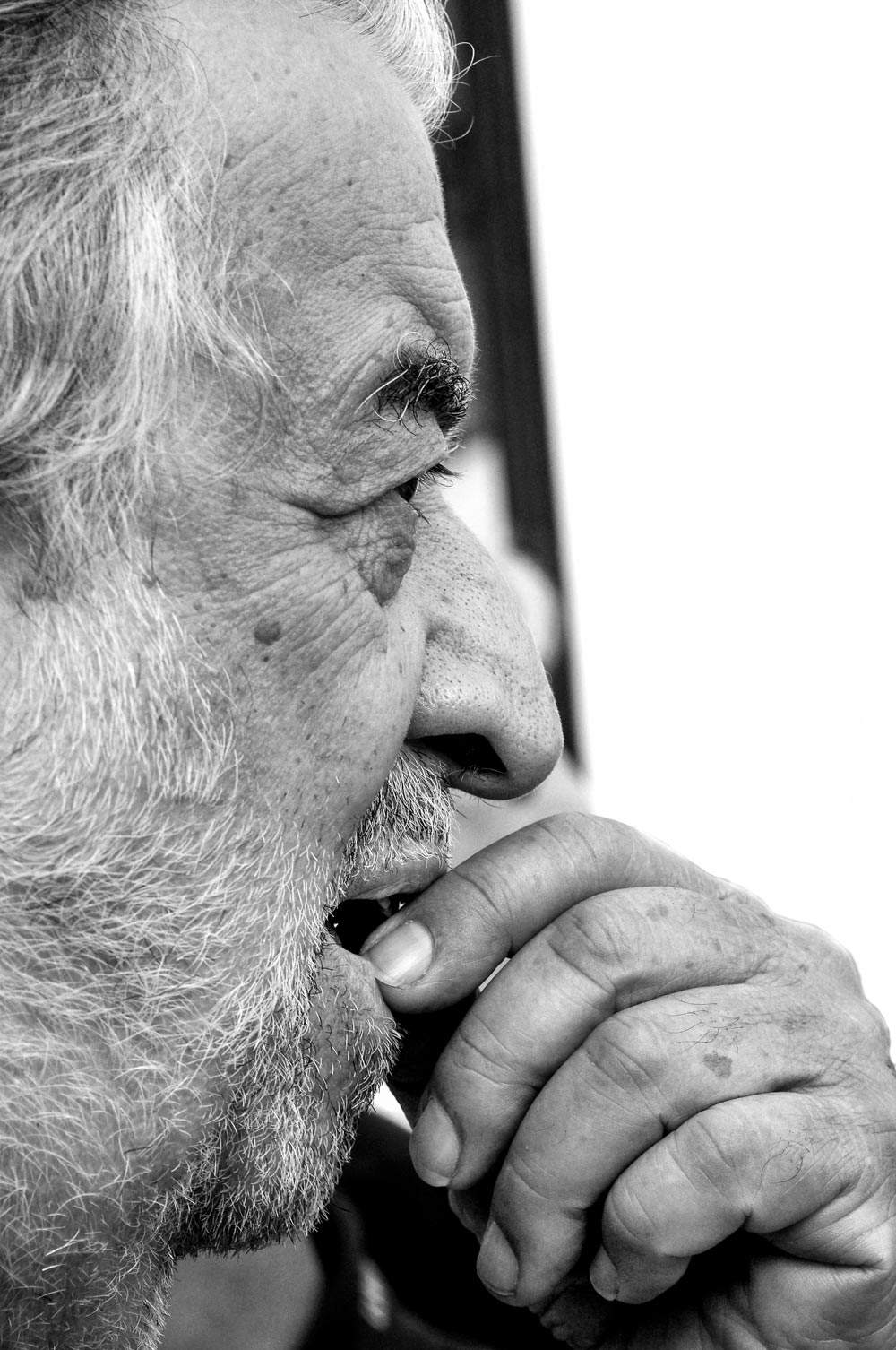

Giovanna Dal Magro

Giovanna Dal Magro Giovanna Dal Magro

Giovanna Dal Magro Giovanna Dal Magro

Giovanna Dal MagroIs there a particular experience in your career that you would like to share?

I have always been driven by a kind of momentum, a tension toward discovery and exploration. I needed to end the day dragging myself through exhaustion and with the firm knowledge that I had seen as much as I could. For some things I was literally disastrous: when a camera didn’t work, I didn’t know what to do to fix it, and when digital took overbearingly strong hold I had to learn everything all over again, but I made up for my small shortcomings with a kind of “third eye” that allows me to see lightning-fast what most superficial people miss. When I was in Cancún, where we even slept in hammocks because of the lack of hotels, it seemed to me that from the cab window I could see a tiger on the third floor of a building. I had to know immediately if I had only imagined it, I asked the driver to stop to go check it out better, and that was how I met Pepe, a man who had spent all his money to save big cats. I have been afraid of many things in my life, but animals have never been among them, and when I discovered that a very elegant leopard was hiding behind that door I was pervaded by an endless excitement that led me to take some wonderful photographs and, later, to become friends with the feline, who let me pet him gently on the head. My third eye was also activated in China during a bus trip with a group of journalists when I thought I saw a field of bright red spots. Fortunately, the garden I glimpsed was near the hotel where we were staying, and the next morning I woke up at dawn, while the rest of our little world still slept, to go investigate. I discovered a spectacular installation of red umbrellas and begged the guard on my knees to let me in and he, probably out of exhaustion, agreed. But there have also been horrible experiences from which I have had to claw beauty out of, such as when I recently broke my femur and had to stay locked up in the hospital for two months. While I was bedridden the days went by with tedious slowness, but fortunately one morning some workers arrived to do some work on the roof of the structure in front of my window, and I, with extreme care, again set out to take pictures documenting the progress of the work. It was a breath of fresh air and I felt life flowing gently again.

In today’s world, social media carries a lot of weight and it almost seems as if everyone can be a more or less improvised photographer. How do you think this work has changed and will change because of this?

Yes, today everyone thinks they can become a photographer with social and that is not the case, but I don’t think the quality has deteriorated because of social, but rather because of the ferocity of the market. This world of today doesn’t seem to care about a job done well and justly paid, but prefers shabby things that can be paid as little as possible. It is the indescribable greed of human beings that is the real problem, and social sometimes seems only to exacerbate it. For excellence one has to study a lot, but I am convinced that, in certain places and situations, the beautiful photograph can always happen even by chance, and cell phones make everything much easier. If only they had been there even when I was a girl I would not have missed so many opportunities, like when I met De Chirico. Because when you left your camera in the house you were not allowed to go back by pausing the whole world, but it kept running fast, those interesting people passed by, the flowers wilted, the clock was ticking and all you could do was capture that instant in your mind.

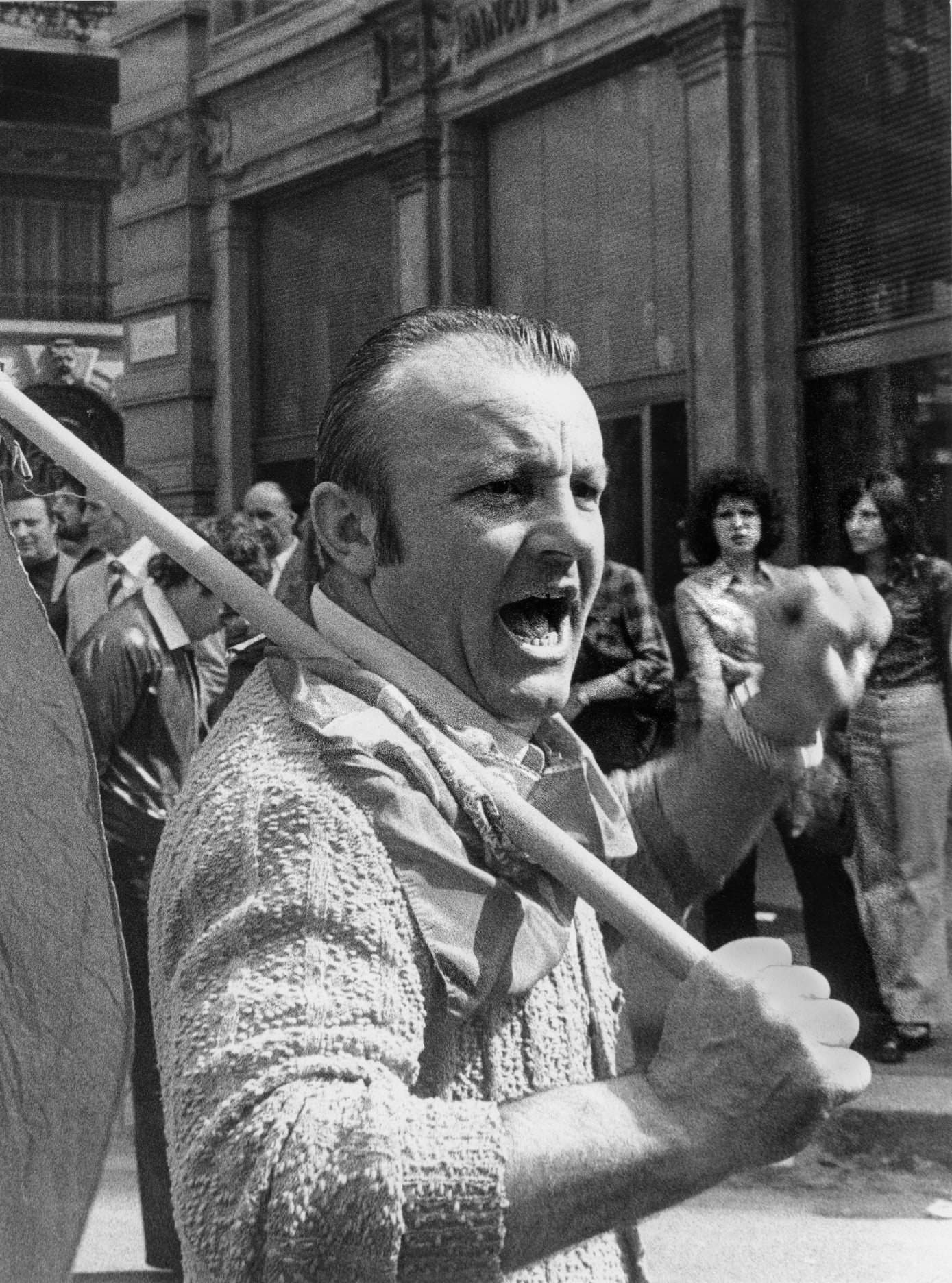

I think photography is art of the present that forever crystallizes the past, and so you did by surgically documenting the post-1968 decade with photos of marches, political demonstrations and Unity festivals. What motivated you to document it and how did you choose to do so?

The essayist Roland Barthes claimed exactly the opposite, that photography is the death of history, but I disagree: photography allows people to relive the past even if that past is not theirs and makes it real and tangible. I chose to document the post-’68 decade because it was simply part of my life, part of my way of being, and I used to attend every event with my greatest friends from the Academy. We would head, always together and with infinite naturalness, to see all the exhibitions and every little thing that was happening in the city, we wanted to actively join strikes and festivals trying not to miss anything. We shared important life experiences that allowed us to stay connected forever. These experiences, which were exhibited at the gallery “The Million” for the 2018 exhibition curated by Alberto Maria Prina Anni 70 .When we thought we were changing the world, and among the photos, taken in the studio, of Marina Abramović, John Cage, Andy Warhol, Franco Vaccari, Gillo Dorfles, Dario Fo and others, stood out the consequences, hopes, dreams and struggles that I froze forever, through my lens, in those fleeting moments of history.

What are the difficulties an aspiring photographer faces and what are your recommendations?

When you are very young, you possess the arrogance and tenacity of those who would like to conquer the whole world, but it is most important to be humble and ready to learn something new from those who know life, not better, but differently. It is necessary to experiment and take the first steps in this strange work with perseverance and tenacity, remembering to behave equally with everyone and without making distinctions between those who live on the margins and those who, on the other hand, are at the top of society because both will have very important and equally enriching stories to tell. I would like to say, to the girls and boys who will undertake or are already undertaking this work, to approach it as a journey and to keep collecting experiences by listening to every life story and always learning from everything and everyone, because when it comes to photography you have never really arrived, you always discover something new. But most of all I would like to tell them to follow their sixth sense because that is never wrong.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.