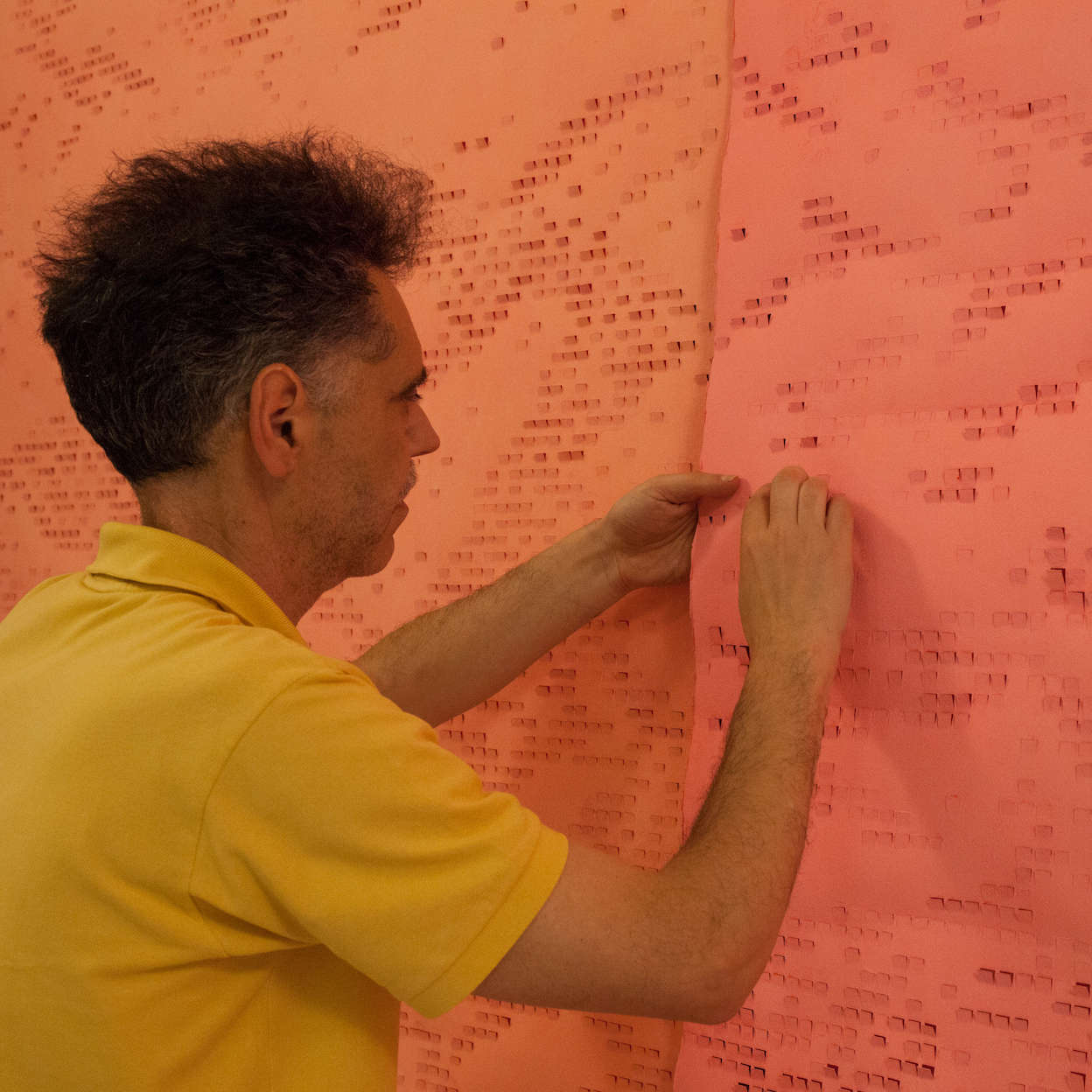

Arianna Giorgi (Milan, 1965) is a visual artist born in Milan where she has lived, worked and exhibited since the late 1980s. She studied at the Brera Academy and then, after a brief period in Paris, continued her training in the 1990s in the context of the Casa degli Artisti in Milan. His research focuses mainly on sculpture/assemblage and branches out into a multiplicity of forms and materials, including stone, which he assembles with other elements to arrive at an accomplished sense of the idea. His gaze rests on reality, nature and art in a poetic, but also critical and sometimes ironic way.

GL. Hi Arianna, often in the events that lead on the road to art the mythical age of childhood plays a strategic role, able with its suggestions, even many years later, to activate mental processes of fundamental importance for later developments, was this also the case for you? Tell.

AG. I think so, at least in part. I realized this late in life, over the years. You get older and you try to get clarity about the past. There are multiple things that I identify as determinants. That, in some way, I revisit (relive as well) in my approach to work. Some are part of family cultural backgrounds. Others, sunnier, are related to what I had around me in the happy moments of my childhood. I think the traces that those experiences left behind led me, at some point in my life, to choose to operate in one way rather than another, without my being fully aware of it.

I remember once commenting on a photo of Abramović and Ulay’s performance at the G.A.M. in Bologna in 1977, you told me that you and your father also passed between the two artists-what interests did your family have in art?

I’ve been thinking about that for a long time. Especially visiting the recent Abramović exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi. Strange, I’m not so sure anymore. That is, I no longer know if it was a concrete visit or a false memory. There had been so much talk about it in the family, evidently, that it made me tactile, in memory, something that perhaps, never happened but that, certainly, stayed with me. In fact I used to place Imponderabilia at the Venice Biennale, where we went, with some regularity, even when I was a child. But in the end it is not so important whether I saw it or not. In ’ 77 I was 12 years old, an age when one is still very permeable and suggestible. At home we talked about art, and I started going to the designated places from an early age. Especially the places of ancient art. My father had a great interest in literature and art. He was a very learned and curious man. He used to take us to museums. But (through no fault of his own) he could not always convey these interests to me with serenity. The “endless hours” in front of a painting having to be still and silent but mostly passive, did not help me grow. Probably, some details began to make their way into hidden places in my mind. That yellow and white matter “kneaded in some way” that “magically” became a very fine gold detail as soon as you moved a little away from a Rembrandt painting, for example, has remained in my eyes since childhood. Without the perception that it was an artifice, but a profound ability. My first experiences at the Biennale, on the other hand, were outings where I literally understood nothing, but I had fun. There was open space, there were “strange things,” there was Venice. What marked me most, which I recognize in part in mature work is not, however, primarily related to that. Rather, to what settled in parallel, during long vacations in a Greece still untouched by tourism. One would get there in two, three-day drives through Yugoslavia. Then the surprise: a mixture of nature and art. The astonishment in front of the Parthenon, which I remember very white, silhouetted against a blue sky. The austere and strong caryatids, imprisoned in their role as columns, the korai with those hairs, those draperies, those smiling faces. And the kouroi, who in their presence appeared uncouth to me, and I could not get over it! Empty Epidaurus, not a tourist, where the acoustics enveloped you-a miracle that cost us the wrath of the gatekeeper after my father placed a tape recorder playing the Casta Diva aria sung by Callas in the center of the orchestra. The snow-white temples next to beaches of ancient shells, Roman quarries of crystal-clear marble (Thassos marble) where I would get lost observing each block and how it had changed through erosion. The sea had fashioned a small turquoise pool with black urchins dotting it: stars the color of night. The altars by the roadsides. Then the village store with its trinkets, the sparkle of the hardware store. The owner, an old man, was called “Mr. Cephalonia” because he had fought in the historic battle. Yes, that was my most desired “toy store.” I would return to Italy armed with colorful plastic bowls and small shiny objects, such as nuts and bolts, and shells stolen from the sea. I am reminded now of how much I suffered from not having access to that door at home, in Milan, which closed a well-stocked toolbox.

As a child did you enjoy drawing, manipulating matter?

As a very small child I invented a game: I used to turn dark soil into a bucket and make the best chocolate ice cream in Milan out of it! Fortunately, I did not have the vocation of a cook. I liked to reinvent what I found. I would knead what was there and there was only the soil in the pots on the terrace. There was no dirt in the house. But you could draw. I used to draw a lot but I didn’t have any guidance. I lived with my grandparents. I also found pictures of me in my dress and big rocks in my hand.

What schools did you attend?

In first grade I had a teacher whom I loved. She also taught us art techniques. Unfortunately, I went to primary (that is, I was enrolled the year before) and in second grade I changed teachers, a trauma! Then, no school that I was ever fully passionate about. I have, for the most part, very bad memories of school. Of school as a physical and human environment. I was put in a private institution of secular nuns because it was close to my grandparents’ house. So the private school circuit, where I was not really in, continued even in high school in very bad institutions, and my disinterest in studying grew. But I think it was something other than disinterest. When a subject excited me, I would jump into it. I was good at ancient Greek, of course. I think there is a deeper reason for this, a very serious fact that unraveled my very early childhood. My mom, who by the way was a painter, died because of a wrong transfusion a few days after I was born. A shock that scarred everyone and is inescapable regarding what was decided for my schooling affair, at least until I came of age. I always thought that to be an artist you needed depth of thought, and in order to be a classical student I tried everything. But when I tried to enroll in public high school and was rejected as a private student, it was quite a blow. I continued with my head down in schools that were unbearable for me. I had no alternative and it did not end well. After two years of gymnasium and a year lost in “meditating,” I succumbed to two two-year art schools (private, of course) that allowed me, by then of age, to enroll in Brera. I have always regretted that I was not able to build a more organized thought, a more articulate knowledge, the gift of synthesis. I have read a lot since I was a teenager, and now I find myself struggling much more. I hope I have at least “forgotten by heart.”

Already “forgotten by heart” great. At the Academy, how did things go?

Yes, Agnetti’s oxymoron accompanies me, today, when I observe the inconsistencies and discontinuity of my early training, my current contradictions. My removals. It helps me to make living matter of them and to persevere in a critical dialogue with myself. Not without self-mockery. In the Academy I finally found myself in a place where I did not feel oppressed. So, paradoxically, also less rebellious or inconclusive. Of course, they were up to something. Often around at night, after openings. But there was a deep connection with art. I rediscovered the passion of going to exhibitions, of going back to the Biennials with a different outlook together with other students with whom you stayed and talked, and laughed, until you got locked out of dive bars and were left without a bed. I had a lot of fun. Maybe too much, but I also worked. It was an important time.

Who were your peers at the time and what important encounters did you have during those years?

It was a formative time, so going to exhibitions, I hung out with a little bit of everybody and a little bit of nobody. Of encounters I made many, as one who attends an academy.

Was yours from the beginning a work on sculpture?

In the beginning I was painting. I was doing various experiments in two dimensions. When I brought a work to class and the teacher, Luciano Fabro, told me that if I wanted to do those things I should, at least, try to do them well (“grammatically correct,” I think he said) I realized that my painting was the expression of an outlet more than the search for a form, but above all, painting-making, in the end, no longer satisfied me. How could I get, on the other hand, to the yellow and white matter that became a very fine gold detail, mentioned above? Did it make sense then? My imprinting, my parameters of quality in painting were those of the greats of the past. I had them in my eyes since childhood and perceived them as distant and unreachable. Above all, it was, for me, anachronistic despite the fact that these were precisely the years of citationism and return to painting. In my Art History class I was studying the experiences of the 1960s/70s. I began experimenting with small sculptures and installations that I kept private. The idea of art as other nature, the idea of making art reality, the freshness of using things I had around involved me. Perhaps, but I can only guess today, it was a way to recapture the wonder experienced in Greece as a child.

Are awe and wonder still your favorite tool for approaching the world today?

Awe and wonder are rare sensations in adulthood. In an age where, by the way, the media and its now constant use, lobotomize us. Let’s say I try to put myself in the attitude of being amazed. But I do not forget that amazement is a moment of suspension, of enthusiasm but also of numbness. It lives in the moment; it has no duration. If it is meddled with memory, it is not free from moments of melancholy or nostalgia. It is up to the next step to process it, to make sense of the awe, wonder and even melancholy of the memory. Otherwise I would get lost in the daze, and that wouldn’t be so bad, given the times. But as a human being I have responsibilities. As an artist I have also taken responsibility.

Can you talk about this? What do you think are the responsibilities of the artist?

Every artist feels his or her own responsibilities, I suppose. Thinking, understood as reflection, is not separated from making art. Pensum comes from the Latin word “pendere” meaning to weigh. Pensum was also the amount of wool weighed for a certain purpose. I realize, thus, that thought manifests itself from concrete forms and then returns to them. Here wool could, very imaginatively, represent the raw material that we turn into the thread and then into the weft. Interwoven with the warp, the weft composes a form. In the end, among many, it seems like a metaphor for art making. In particular, I respond to you by trying to explain a way of working that I have been cultivating for many, many years. I see, for example, a stone: it looks interesting to me, beautiful. I pick it up. Looking at it I let myself go fulfilled by the boundless places I glimpse in it, by the emotions I feel. I lose myself in it. I surrender myself to the amazement that a stone arouses in me! I know this is childish, bordering on the puerile because of its paradoxical nature. But this bewilderment where “s’drowns il pensier mio,” to trouble Leopardi, is the prologue to the next moment, which is when I begin to think about what could really happen using that stone as an element of a work. A transition occurs between two dispositions of mind. The first is the passive phase, of enchantment, the second is reactive, of exploration, of observing that rock, that stone as a possible element of an art form. It is a hypothesis of the future that lets you enter the present. But it is necessary to create the conditions for it. That is, to be aware that a transition must take place. I do not forget the original experience but I move toward the sphere of inquiry through the cognitive and constructive elements of art making. Sometimes it pains me to leave that corner. To risk losing the “toy.” I am never certain, a priori, that its transformation convinces me. But this transit, this passage of temporality is necessary for me, it is consciousness of making and part of my responsibility to the work.

This praxis, seen from the perspective of the totality of the work, seems to contribute to tracing a totality that is, however, destined never to show itself in its entirety but always to offer only fragmentary visions of itself, and so ?

The one above is an example related to a specific mode. In other works I start from different assumptions. With respect to the totality, if you mean the totality of my work, there is no formal continuity, if you can call it a practice that is repeated over time. Rather a poetic continuity. I don’t even see fragmentariness. Rather I would say that from the multiple one arrives, or would like to arrive, at a recognizable chorality from the point of view of the sensitive. Although I work very often with fragments, each work, even tiny ones, has a precise and autonomous identity that tends, attempts, to take the fragment out of its state of being. To assign it a peculiarity. In itself, the fragment does not interest me, not as a subject. Rather, I see it as something that offers itself with its history and that, with its elapsed time, invites me into other unknowns.

Let’s talk about poetic continuity, what are the fields you are interested in investigating?

I do not investigate specific fields a priori. It is a given that art and nature are part of my being. If anything, I act the other way around. I start from the idea of a work by developing its research. I identify traces and kinship between physical things and other things. The outer, surrounding space is a panoramic place, a complex landscape from which I draw ideas that I subsequently develop. I place myself in a contemplative disposition to come to internalize the reality I observe and move toward a secularly metaphysical vision. I try to see through the mind, peering with my senses inside the potentiality of things. Ultimately that means imagining.

Let’s talk now about some of the work I would start with the cycle of works with metal, a sample of which you recently exhibited in the exhibition Il Numinoso curated by Giorgio Verzotti at the Building Gallery in Milan...

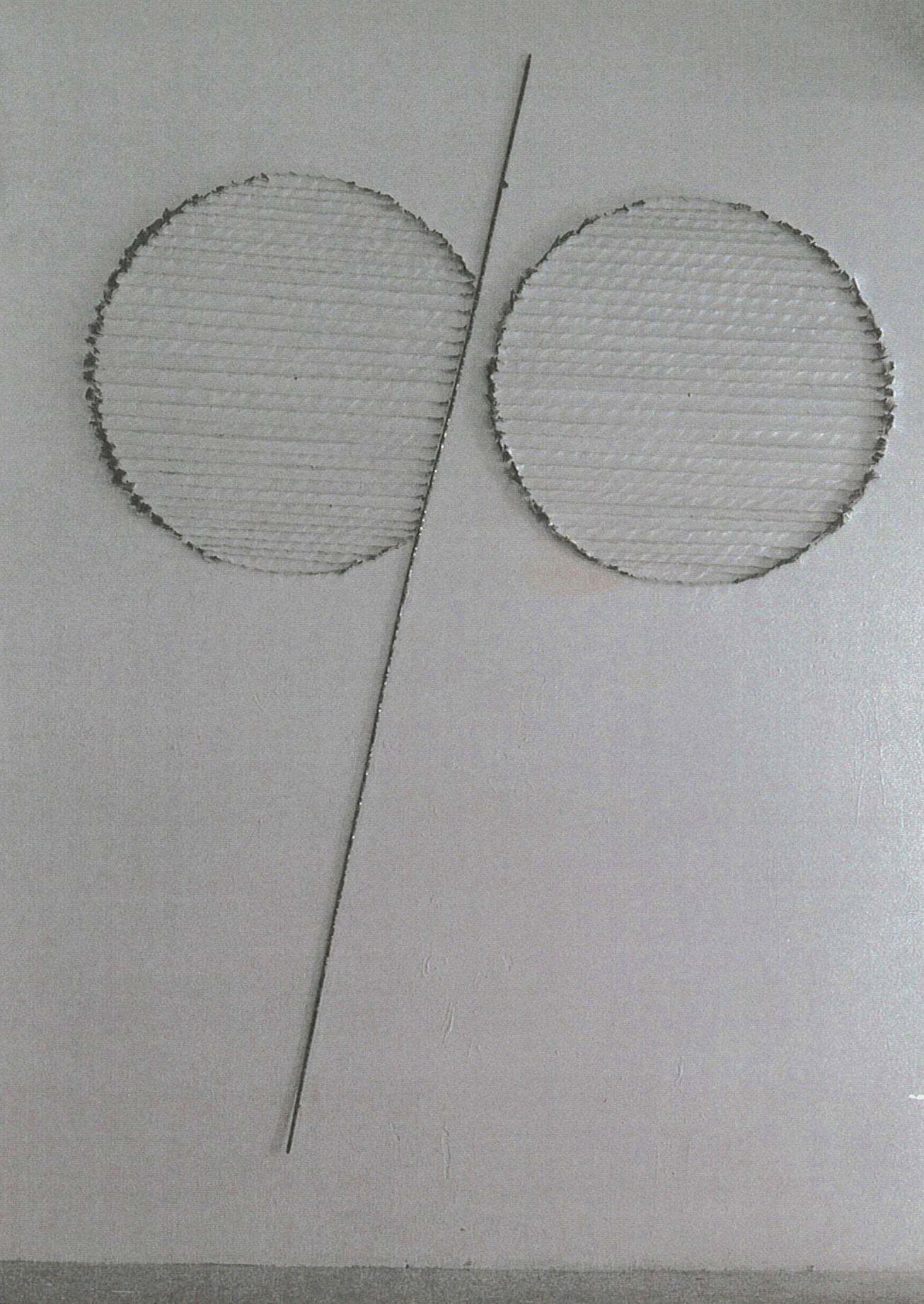

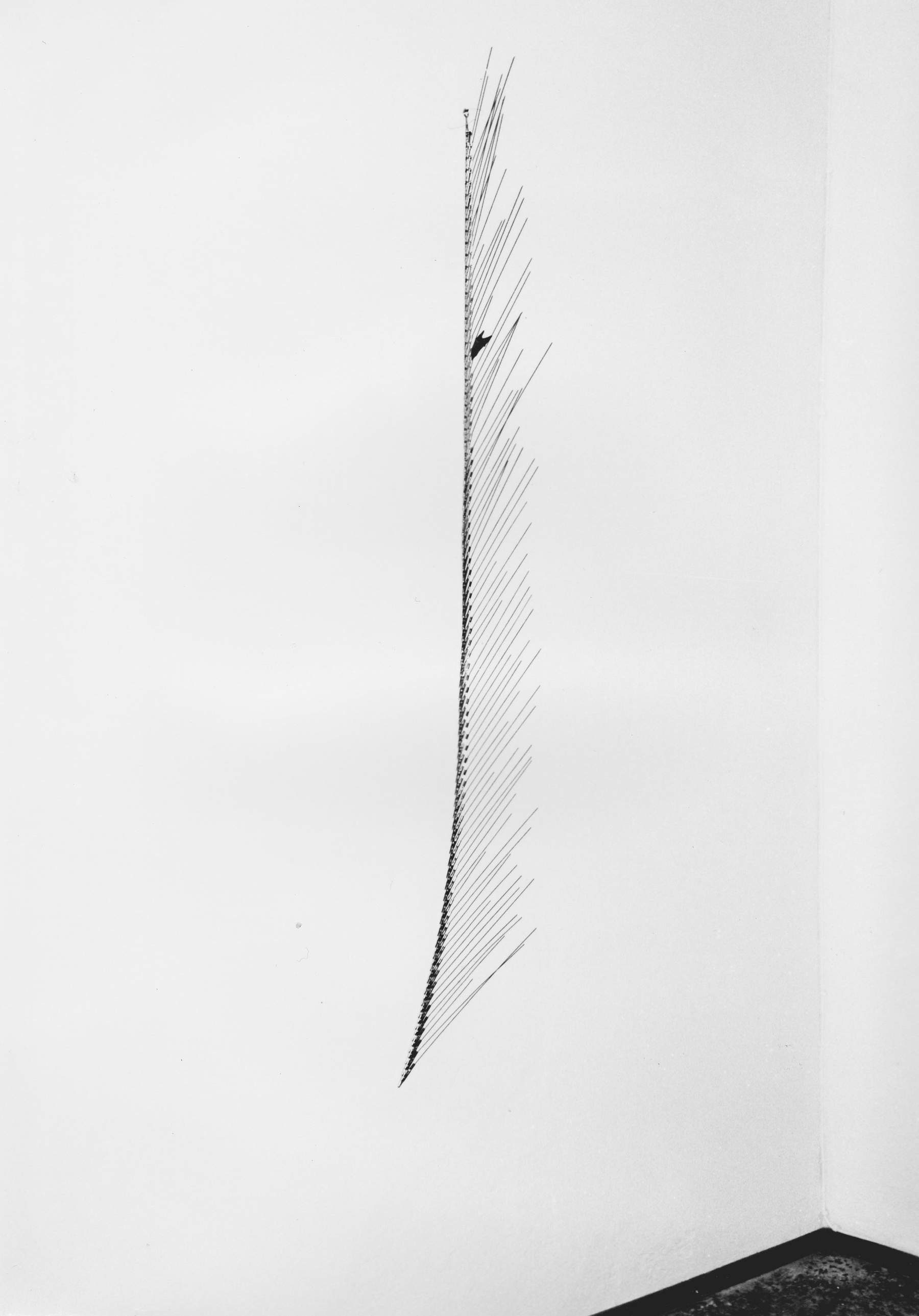

I started using metal tape (fired brass, raw brass, bronze, aluminum) many years ago. A practice that returns with different forms and meanings. Early works, such as the 1993 Grottesche , were derived from observing those painted, or bas-relief, moldings in Renaissance palaces called precisely “grotesques” but much simpler than the Roman-derived namesakes. Decorated linear bands that take a back seat to the frescoes but have the ability to delineate the wall space. I was interested in this aspect and the way of defining space through plant elements. My works were made with essential gestures. Brass tape cut into simple folded segments so that they could be supported directly to the wall by a vertical row of nails. Something extremely simple. I was not trying to shape leaves but to get the feeling, the perception of a vegetal flow. I also made circular Grottesche by welding the ribbon to an iron frame. I called multicolor Gro ttesche those few made with different metal ribbons and Golden Grottesche some more elaborate installations (with chains and other elements). “Golden” to differentiate them from the first ones and because I thought of them after a visit to the Domus Aurea. At the same time I was observing the potential of the reflection of the metal ribbon and how it made the light reverberate such that it became an element of the work. With this mode I made some works such as Near the Sea, 1994, Luna-Mare, 2011 and also the one you mention, Ring of Fire, 2022.

The idea of the reverberation of light reflecting around the work is a dimension that I also investigate in my work, it seems to me a good way to expand the dialogue between the work and the space, are you also interested in this kind of dimension ?

Absolutely yes, I share. Although not all my work is based on this, light is living matter. There can be light intrinsic to the material or light reflected by the material or the medium we use. Either way, the relationship it creates with space is substantial.

I wanted to ask you to talk about works like Lilith and Black Moon.. ..

I made Lilith after the Ara, festive works about the relationship between artifice and nature that I had caught during a trip to Brazil. Afterwards, I was like drained, I didn’t know exactly where to go with it. On the one hand I was closed in on myself, on the other hand I had a great desire to tour the world both real and, also, virtual. There was more and more talk about the great changes in the global order, about the Internet. I hoped for a unified world based on the meeting of cultures, but right next door, the Balkan wars suggested otherwise. We were approaching the second millennium with great hope but also with apprehension. Picking up the thread of memories, of their sudden surfacing, I went back to thinking obsessively about a distant trip to India. I was more or less 13 years old. The first breath in that air saturated with water and spices made me feel apnea. It suffocated me. Visibly sick people were coming toward me in search of something. The upheaval had forced me into a hotel room to cry for a whole day, but in that stop I was able to strip away all fears. My eyes opened. The eyes filled with pity. The whiteness of the sleepers scattered to cover the huge esplanades of Delhi, or Bombay. The red spit of betel chewed at every street corner that looked like blood. The Hindu funerals. How I loved those funerals of scattered flowers and white robes! At least that’s how I remember them as a little tourist. The painted caves along the winding Ajanta valley and the temples where the whiteness of Greece gave way to an animality of form and matter, a carnality of stone. This sudden nostalgia at a time where the constant feeling was the latent loss of centrality, of one’s cultural references, of the fact that something was changing, even within myself, but I did not yet know what, led me to Lilith . “Lilith is like the bend of a river saturated with flamingos that soar at the first ambush,” I had written in a text. As if to say that when you are about to do a work all the senses are on alert but, this time, the alert also picked up a pitfall. I was sitting on discombobulated ground and sensing its change with awe (and trembling). Renewing the skin, the surface on which the depth of the artwork lives and germinates, which, in that moment, I needed to conceal, to protect in an inert silhouette, yet, redolent of rosy valves. Diverting the paradox into the idea of a mute, a lifeless shred because its vitality had already flown elsewhere. As flew immediately away, in ancient religion, the idea of a first woman made with man and not for man. Just after Lilith comes Sick Stone. Then, in 2000 Pelle. Works that, unlike their predecessors, are the result of a restlessness. Recently, in 2017, no longer having the first one, I made a variant of Lilith. Together I made Black Moon. A work thought of at the time, in 1998/99, but then forgotten or perhaps removed because it was precisely the removed that was involved. I think I had some discomfort in going into that quagmire. Instead of pink lactarians and pigments, or salt of the same color, I used large shells of peoci (or muscles or mussels) turned so as to bring out their inner color, pearly gray, almost silvery, of ambiguous luminescence and held in a kind of clay circle covered with black, freshly treated sugar paste. Resting on an orbit of white salt mixed with vegetable charcoal, Black Moon refers primarily to the unconscious. A dark mental place, free from all logical control that, like Lilith exiling herself from nascent humanity while remaining eternal in the imagination, hides in the depths of the psyche exiled from consciousness but, of the latter, a constant harasser.

Arianna do you often make second versions even at a great distance of time of some works where does this need come from?

It does not happen to me often because I have never sold so often, or lightly, so I still have several sculptures. In the case of Lilith, of which I had immediately had a cast made of a detail that I wanted identical, a stone of a particular shape, the reason was that Black Moon, too, had to have that stone (shape) since it is, in essence, one subject. Also, in case I sold it, I could display it without the hitch and complications of having to borrow it. And so it was. I sold Lilith in the early 2000s and in 2017 I redid it and, together, made Black Moon. I think it would be useful to do the same thing for certain works that I care a lot about or are particularly fragile. Different matter for more installation works that I often adapt to the space. Or which undergo small variations when assembling them.

Here this is another fascinating aspect the dialogue with the space, can you talk about it?

More than dialogue with the space I prefer to use the term relationship. It implies a greater physicality that I feel very much in my artistic making. Above I was describing to you more installation works. Some may vary depending on what you find where they are installed, and that intrigues me. So, space, for me, is the place of happening. Beyond any project, when you install there is always a dimension of corporeality and accidentality that overcomes and often modifies or renews things. If I think about the making of a work, on the other hand, I think its space is the result of all the steps I take to arrive at what satisfies me. I mean that, subjectively, I feel the space inherent in each of my works as a concentrated memory of the emotional time it took me to arrive at its maturation. It is necessary, however, to constantly rethink the concept of space, time and place and that of matter and the immaterial, the concept of consciousness. Not necessarily to change one’s doing, much less what has been done. But to understand where we are, where we are going and not to be caught off guard. To be inside the time you live, inside what is changing is, of course, substantial. At the limit, even to reject it.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.