Loredana Longo (Catania, 1967) is an Italian artist and sculptor who has built her research around the aesthetics of destruction, a theme that has marked her work for more than two decades. Her practice, which ranges from sculpture to installation, performance to site-specific space design, explores the relationship between matter, body and transformation. His works are often characterized by the use of unconventional materials such as concrete, plastic, plaster and earth, and by the direct involvement of the viewer, who becomes an active part of the artistic process. Longo makes much of her work in the spaces in which she operates, drawing inspiration from the context that surrounds her. In her home-studio in Milan, for example, she lives in close contact with some of her best-known works. The expression “aesthetics of destruction” emerged as a key concept from her solo show in 2005 in Catania, Italy, and continues to be central to her research, highlighting the fragility and potential for rebirth that accompanies any process of deconstruction.

His often disruptive performances offer a reflection on the dichotomy between vigor and delicacy, physical strength and sensitive matter. Longo is able to adapt her art to the contexts in which she works, creating processual interventions that continually evolve. Loredana Longo’s work is distinguished by its continuous transformation, involving not only the material but also the audience, in a dynamic process that questions and reflects the human condition and the contradictions of our time. Her art is a reflection on the tensions of the present, an invitation to look beyond appearances and confront the vulnerability and strength inherent in the process of change. Loredana Longo talks about her art in this conversation with Gabriele Landi.

GL. Often for artists, childhood is the golden age the one where they make their first discoveries of reveries that then return later as time passes and the work evolves: was that the case for you as well?

LL. Born in Catania, a city on the slopes of Mount Etna. In elementary school we were asked to do a drawing about Etna Park, WWF had involved all the elementary schools in the city in this big project. I remember in class there was a child who drew beautifully, as I was not, am not, and never will be able to. I looked at him and admired his technical prowess. I drew a very simple and naive drawing, a mountain with its snow-capped peak, some disproportionate animals, but they all had a task: somehow they had bags in which they could collect the recycling. At the time of the award ceremony, I won first prize; the conceptual value had surpassed any technicality. For the first time I realized I had a small gift, but certain gifts must be nurtured; if they are stifled or misunderstood, they can turn out to be poisons. Perhaps the recovery of materials has always belonged to me, it is part of a family heritage, an education and respect for nature, thanks to my mother’s patience.

What was your first artistic love?

I search my memory for the first true love and I think it was Kandinsky. Thinking back now there is no artist further from my poetics and formal vision. At that time I was fascinated by his story, his use of color and form, and I think that was why I went to a painter’s studio in Catania, where I was living at the time. He had a graphic approach, preferably using acrylics and watercolors. Initially I tried to follow his marks a little bit. I would paint almost transported by the love of color and shapes, but I missed the weight of things. I was always just staying on the surface, everything graphically beautiful, it worked like wrapping paper but covering an empty box. For a long time I remained in that limbo, closer to a kind of stylistic decoration than to art. I was restless, I thought for years that I was almost stupid, too superficial, I was looking for depth but I couldn’t because I didn’t have the foundation to find it. I don’t think I ever had masters, I am convinced that it is always better not to have masters than to have bad ones. I built myself in bits and pieces, little bricks that occasionally collapsed and still collapse, but a person who made destruction his mantra could not expect better.

What studies have you done? Were there any important encounters during your education?

My life has been a succession of bad choices due to rather serious incidents. I could not choose my training studies, so for many years I suffered de-formation. A serious car accident forced me to walk with crutches for many months, I have two brothers and a sister, and for my parents to drive everyone to school became challenging. The choice fell on an equal language school, close to home. Let’s assume that everyone definitely has gifts compared to others; I do not have an easy time learning languages. However, I do have other gifts, and together with my other classmates we set up a theater company, I was writing, doing sets, costumes and also acting. I think it was one of the happiest periods of my life. It was all already inside me, but I was not becoming aware of it. That came later. After other bad choices, which I don’t chronicle, I finally landed at the Academy of Fine Arts in Catania, Painting. I didn’t really do painting, I never liked oil, too slow, pasty, sticky and never stopping. My father had a small modular furniture factory where I used to build my frames, big frames, I used to invest a lot of time in the preparation: I would lay burlap on it, pull it with a puller and apply a base. I would paint on it with earths and vinyl glue. Sometimes I would paint on wooden boards, after serious background preparation I would build my figures, like ancestral forms, rigid, almost textural, natural colors, ochre, burnt earth, black. For the sake of clarity I can tell you that I finished my studies at the Academy with a phenomenal 110 with honors for pictorial merits. From the next day I never painted again. Don’t hold it against all my painter friends, but I find it inconsolable boredom and I hate being bored, that repetition of gestures, the preparation of the canvas, the mixing of colors, licking those shades or sampling big spaces or small ones, the cleaning of brushes. There is a world of other materials outside the studio.

What is the aesthetics of destruction and how does it nesce?

The accident, yet another accident. I lose a kidney. Hospitalization, that long period of inpatient, waiting, patient patience in which my mind devised how to get out of that barbed bed, the catheters, the tests, the days of virtuous abstinence from food and alcohol, concealed and nurtured an implosion. The frustration of inactivity moved thoughts of great operation. I watched a lot of TV, and news of exploding cars, Mafia murders, mingled with news of war around the world. My mountain, the volcano Etna, was exploding and erupting. Only I was forced to stand still. But I had vowed that from my recovery I would think only of me. How does one be reborn from destruction? Rebirth is already an aesthetic choice, you will never be the same as before, but perhaps more interesting, you will carry that wound with pride and it will be the point from which to rise again, with strength. My favorite animal, even though it exists only in the mythological world, is the phoenix. This summer, invited to a festival on art and science entitled Volcanic Attitude, I thought of using volcanic ash. In the performance Black Phoenix, which took place in June at Vulcan Island’s Warm Waters, four girls come out of the water, lie down on the ground following a cross pattern, I then sprinkle them with ash and place palm leaves on the sides, which also have the meaning of rebirth. The performers get up and the shape of their bodies leaves the pattern of a phoenix on the ground. They rise from the ashes. Unexpectedly, this summer, the city of Catania has been buried four times by volcanic ash, as a result of eruptive activity from Mount Etna, sand on us. It is a story that repeats itself over the centuries, in one of the city’s Entrance Gates there is an inscription “Melior de cinere surgo,” Catania has been destroyed about nine times by lava and earthquakes, but it has always and stubbornly risen from its ashes. I am a child of my places. I have always wondered why to rebuild in a place where you are certain that one day, sooner or later, the forces of nature will overwhelm you again, and I realized that the answer lies in beauty. That magical place enclosed between a crater and the sea, black rock and citrus, are not obvious categories, they are gifts from nature, which takes and gives.

Often in your works there are elements taken from everyday reconstructions of home interiors, carpets, vases, glass bottles that you destroy and then reconstruct.

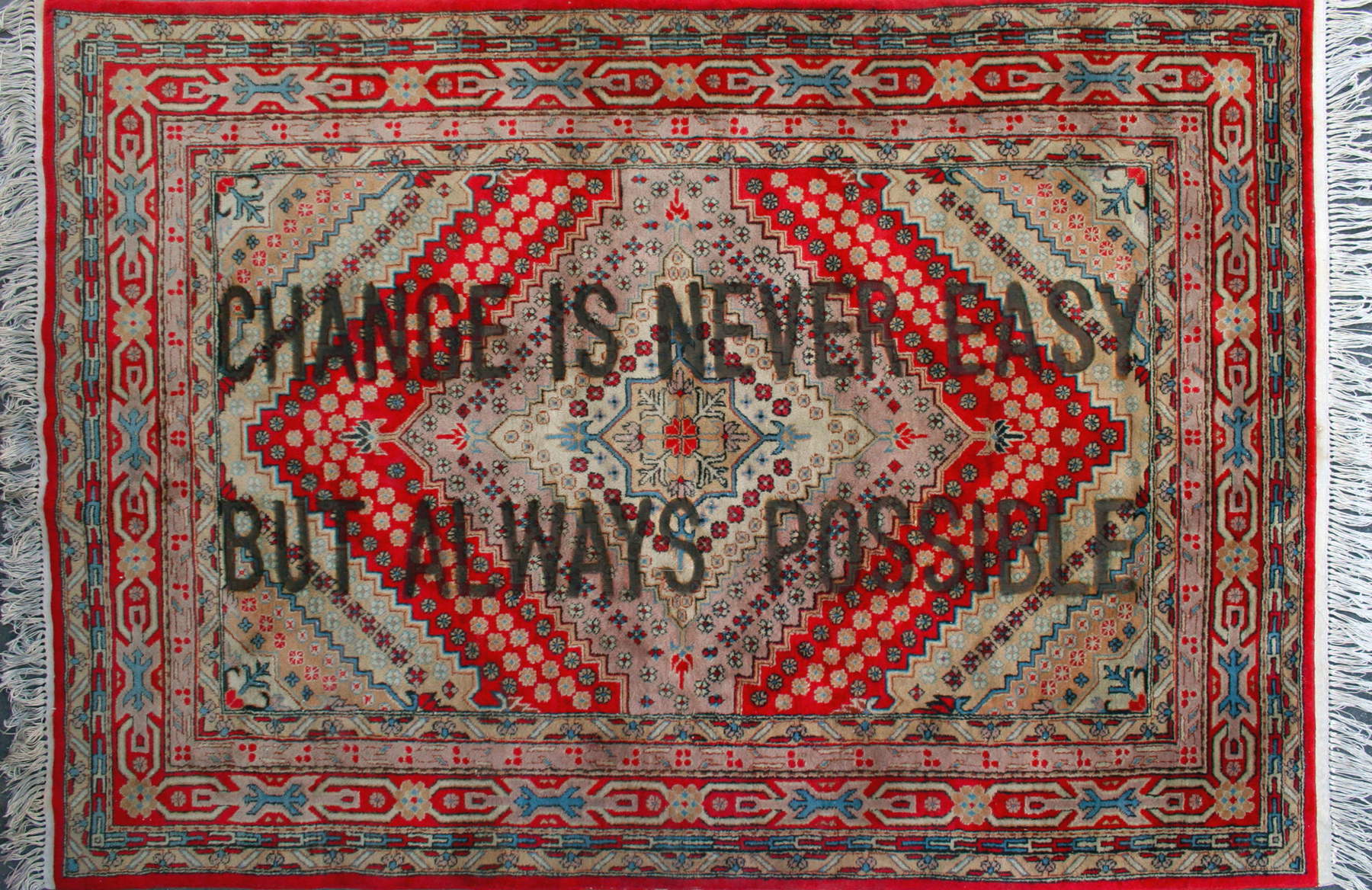

The simplest and most common objects are within everyone’s reach and often the most useful, everyone knows how to use them and they are not full of meaning but you can fill them with memories, moments when you associate them with something. Sometimes they seem trivial to us, but only because we have them at our disposal every day. Everything can become other and other in the other from us. I find it interesting to use objects that are present in our everyday life, to interrupt their functioning and make them become other. I think of my Carpet series, oriental carpets that relive a second life the moment I burn simple phrases, a few words spoken by a Western politician. It creates this clash/encounter between two different cultures, but more importantly they use the same object in a different way. My fire engraving violently etches the surface of the carpet and takes it to a different level than the religious convivial one, turns it into a tabloid in which political slogans stand out.

What value does matter and its becoming have for you?

Matter is what things are made of, it is fundamental, because it has a structure that can attract you or repel you. I don’t like paper and pencils, markers, I don’t like the feel of them, and the noise when I use them. I never draw, if anything with a ballpoint pen. Sometimes I am asked to submit projects, sketches. I do the work directly and send the picture. Any subject matter can become the subject and object of my artistic process, a kind of junkman of the present. I take things and transform them, but not in a “Duchampian” way, I do not elevate anything to a work of art. I perform an almost maniacal process, I destroy it, reconstruct it and then if anything elevate it to a work of art.

Are you interested in the idea of staging the work?

An almost essential component, especially for those making sculpture installations and performances. The risk is to become theatrical, to load the works with too much drama, but I love the dark side of things. In my Explosion series I build real theatrical sets, I leave nothing to chance, they are reconstructions of bourgeois, 1970s environments, reminiscent of the old traditional middle-class homes where the walls of the houses were covered with damask wallpaper. I describe family moments of pure conviviality: family lunches, Christmas dinner, tea time, or rather empty bedrooms. These rooms are always empty, as if waiting for someone to arrive; there is never any human presence. Suddenly something happens, an explosion and objects blow up, something burns, smoke everywhere. I pick up the rubble and arrange it, try to put it back in its original position, glue the pieces together, tidy up. The whole scene stinks, denounces what happened, but to the superficial eye it looks like nothing happened. There is no repentance, I don’t put things back together because the incident provokes in me a need for order, rather it triggers something mechanical akin to manic serial killer repetition. There is no possibility of completely healing some wounds so I try to dab them because I don’t want them to disappear. Why erase the mark?

When you work on an exhibition where you present multiple works how do you tend to think about it?

When I work on an exhibition, I always develop a project, it is not relevant that the works are formally recognizable to the previous ones or to each other, rather that they go along with the thought that animates that project. I use all techniques and all materials, and even simultaneously, sometimes creating confusion in a viewer unfamiliar with my work, but there is always one thought that binds them together. The performance component is always there, either in the form of video documenting something or in presence, but they are always connected. In my latest work in the Victory series, I made an intervention in a rugby field, a huge “VICTORY” sign, almost 50 meters long, made up of the same lawn that I grew taller for about a month. The youth of the Benetton rugby team played a friendly match, I wanted this “VICTORY” to be trampled on, there was no winner, and finally halfway through the video everything goes somber, the color gives way to black and white, and their movements are more like a war march than a match. The video is projected on a wall of the Villa Rospigliosi space, and in the next room there is a large “VICTORY” sign resting on the ground composed of lawn. During the opening, I wore iron soles with 12-centimeter high iron cleats, a variation of the original rugby shoe, and marched, and stomped on the writing. The performance was titled, How to make my Victory. My idea of Victory coincides with a defeat in the middle.

What is your idea of the body and what role does it play in what you do?

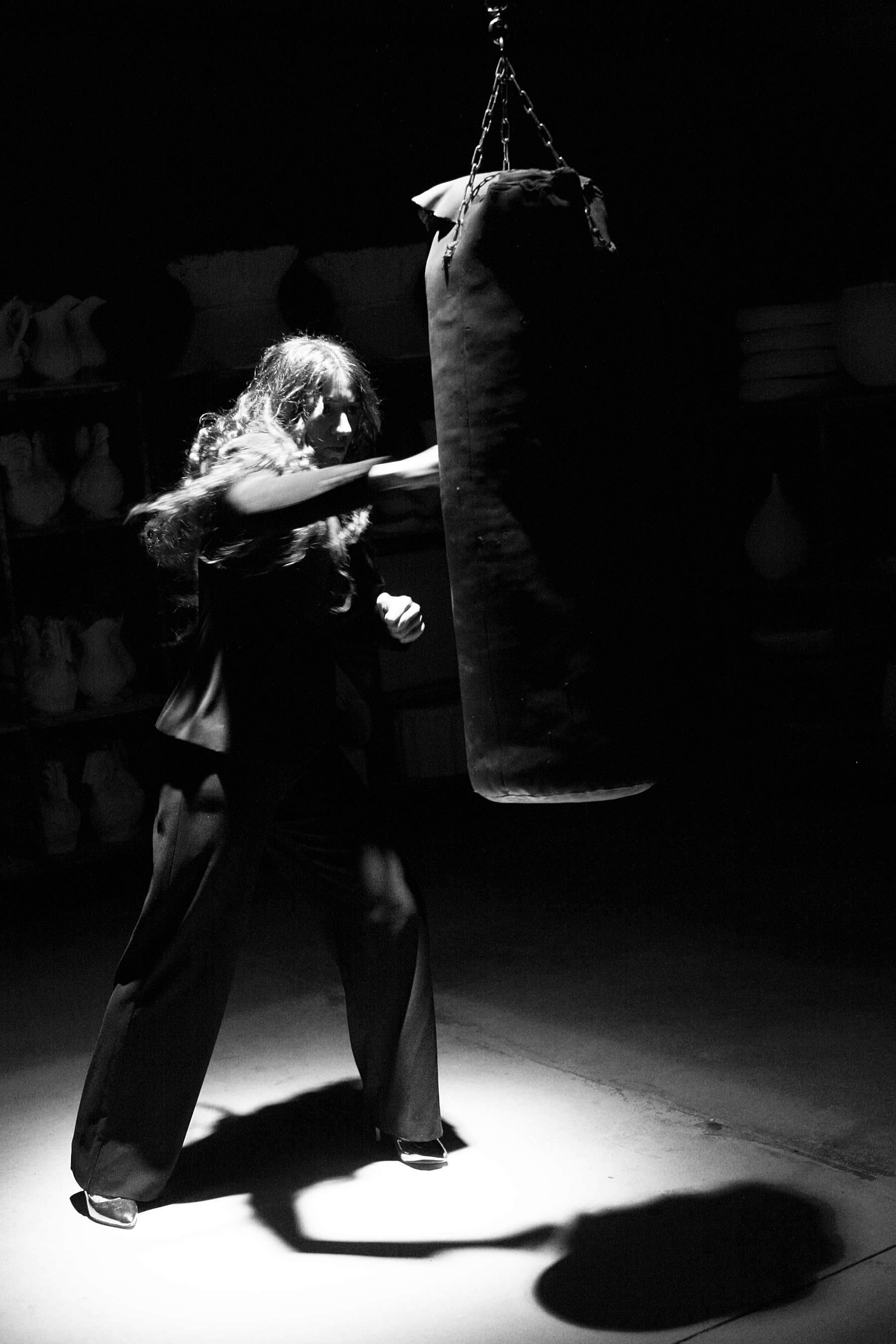

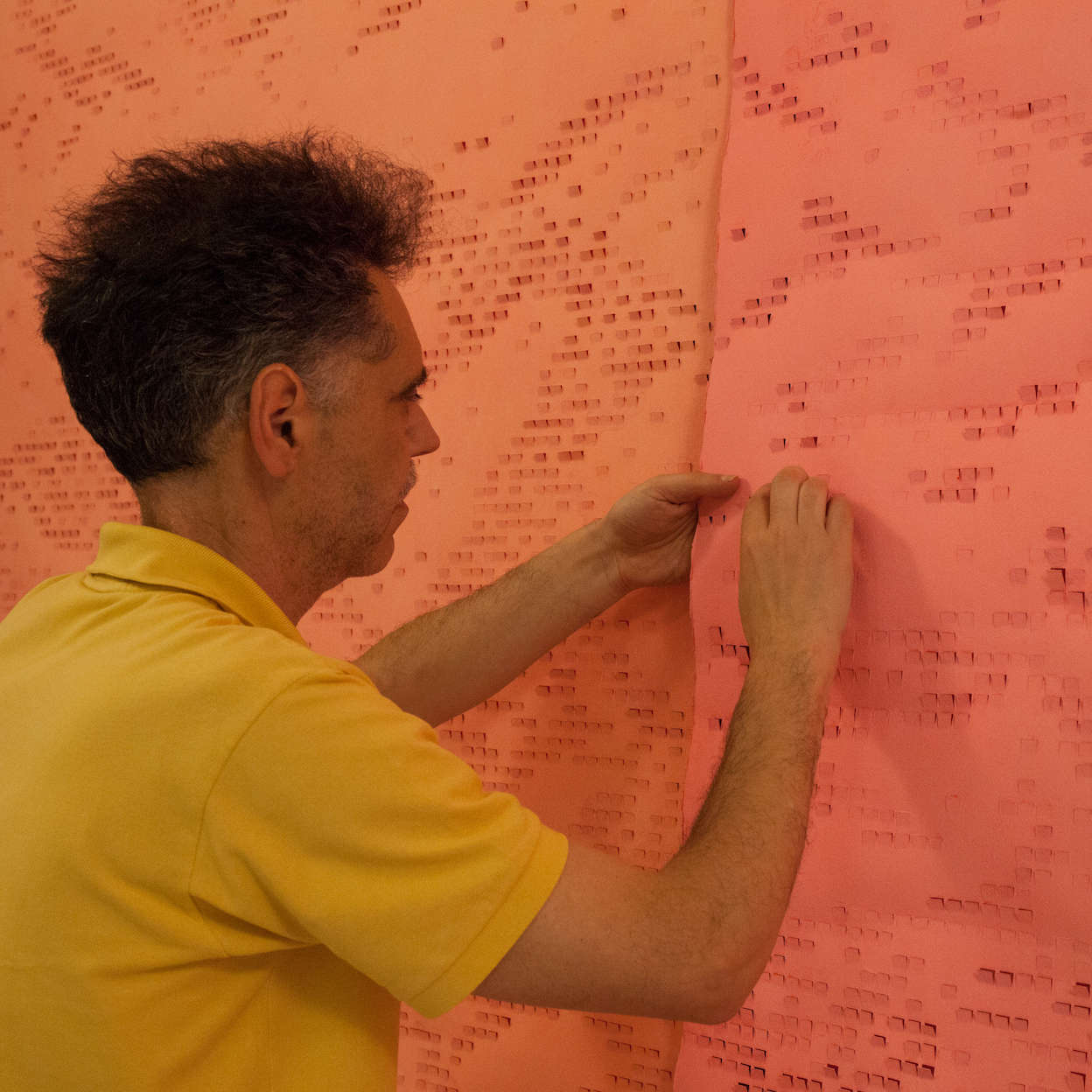

You can tell about things you don’t know just because you can imagine them. Artists talk about themselves and imagine something that is not there, but they always start from themselves. My body is the seat of my movements, happenings and thoughts. My body is fundamental in my work, it is the measure of everything, which does not mean it has to be there in presence, but it determines the structure of the work, the dimension. Immediately after my academic studies, I started on a path that is still in progress, I have never stopped making performances, and this I think is in relation to the truth of being there, as if I am testifying that I really exist and can only test myself as long as my body is able to do so. There’s never any preparation for this, I never rehearse the performance beforehand, let’s say it’s impossible, it’s just a test of strength with myself, a demonstration that as long as my body is there I’m alive and I can do without the work, in fact I often realize it while I’m performing. In Capitonné Skin Wall, all painted black, I throw myself against a paper-covered wall, leaving footprints. The sheets of paper become the patterns used to carve long cuts on large skins the color of my complexion. Each of my marks on the wall becomes a padded panel in which a body seems to be trying to get out. Capitonné is an organ suturing technique, and I could not have found a more apt title. Why do I test my body in this way? I don’t know, but I think it has to do with that relationship with reality and fiction. Is the work always just fiction? I want there to be a relationship with reality and for it to be real. During performance I get hurt for two reasons, the first is because I perform actions that are often violent or strong but the second is more important, I want it to be real, not to look real. If I throw myself hard against a wall I will cause myself pain, if I fall I will hurt some part of my body. I can’t pretend that it hurts me, because it wouldn’t look real. Why do these kinds of actions and do them while pretending to do something? The explosions? They are real explosions, there is explosive material triggered, I never know what happens in detail but I know it will explode and I know how it will do it and it is certain that something will break. If the material is subjected to hard tests, something happens.

Are there any favorite venues for your performances?

The places where I am invited are the places of performance. A very close friend, a very good critic, told me long ago: performance is not theater, it is not acting. I adapt to the place I am in at the moment, without music. Performance has to work in its execution by depriving itself of those effects associated with film or theater. Often music tends to become a kind of soundtrack in some performances, causing a sweetening effect that detracts from the action itself. In Creative Executions, a series of actions in which I explode pots of fresh clay, the only sound, the only action is the explosion frozen in the moment of bursting, then the smoke and what remains, simple cylinders of clay to be fired. The terracotta sculptures faithfully testify to what happened, in the smooth surface of the pots gaps open up, the material is frayed, taken to the extreme of its resistance, it seems that the action of the explosion has fixed itself in those forms.

Are you interested in the idea of precariousness?

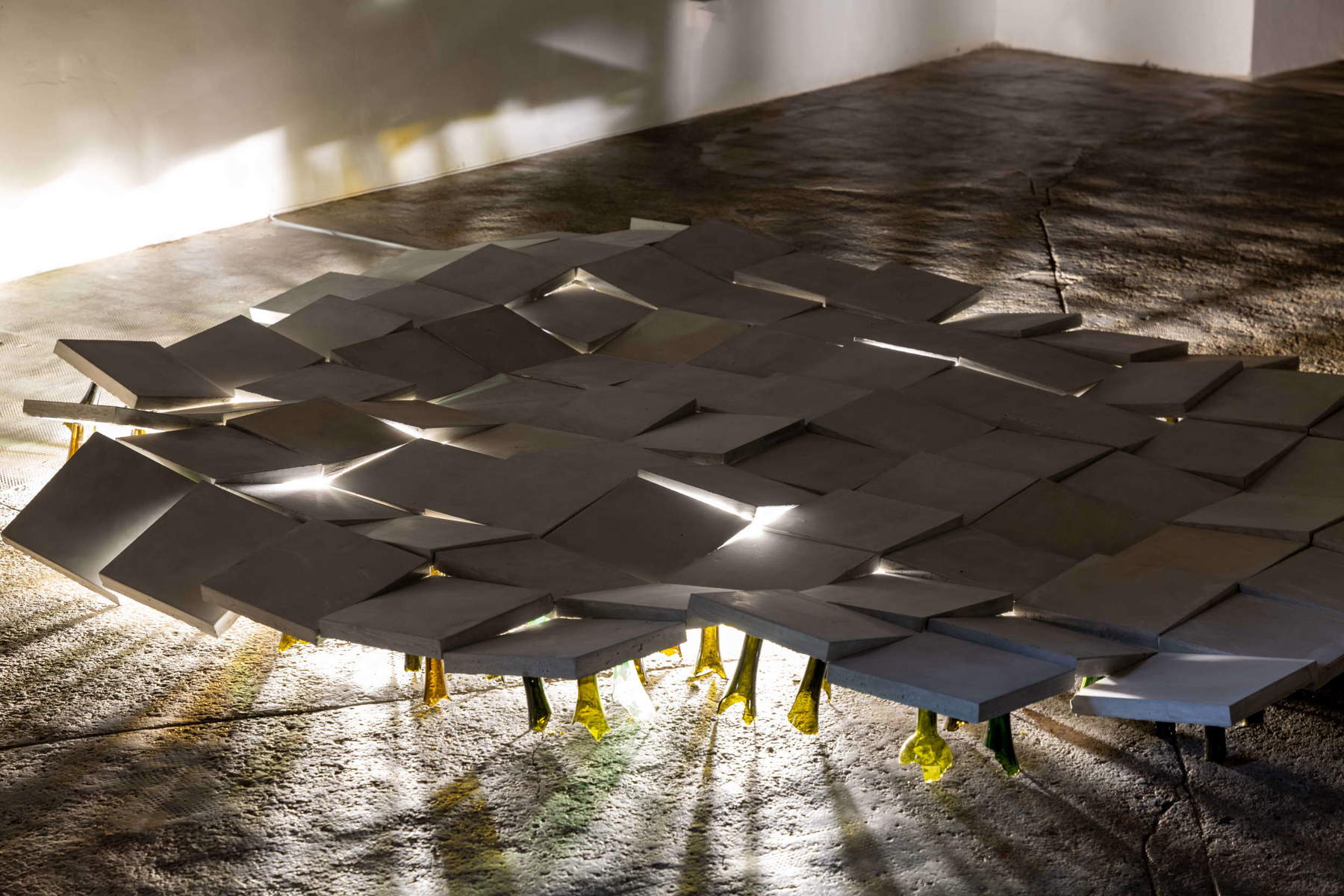

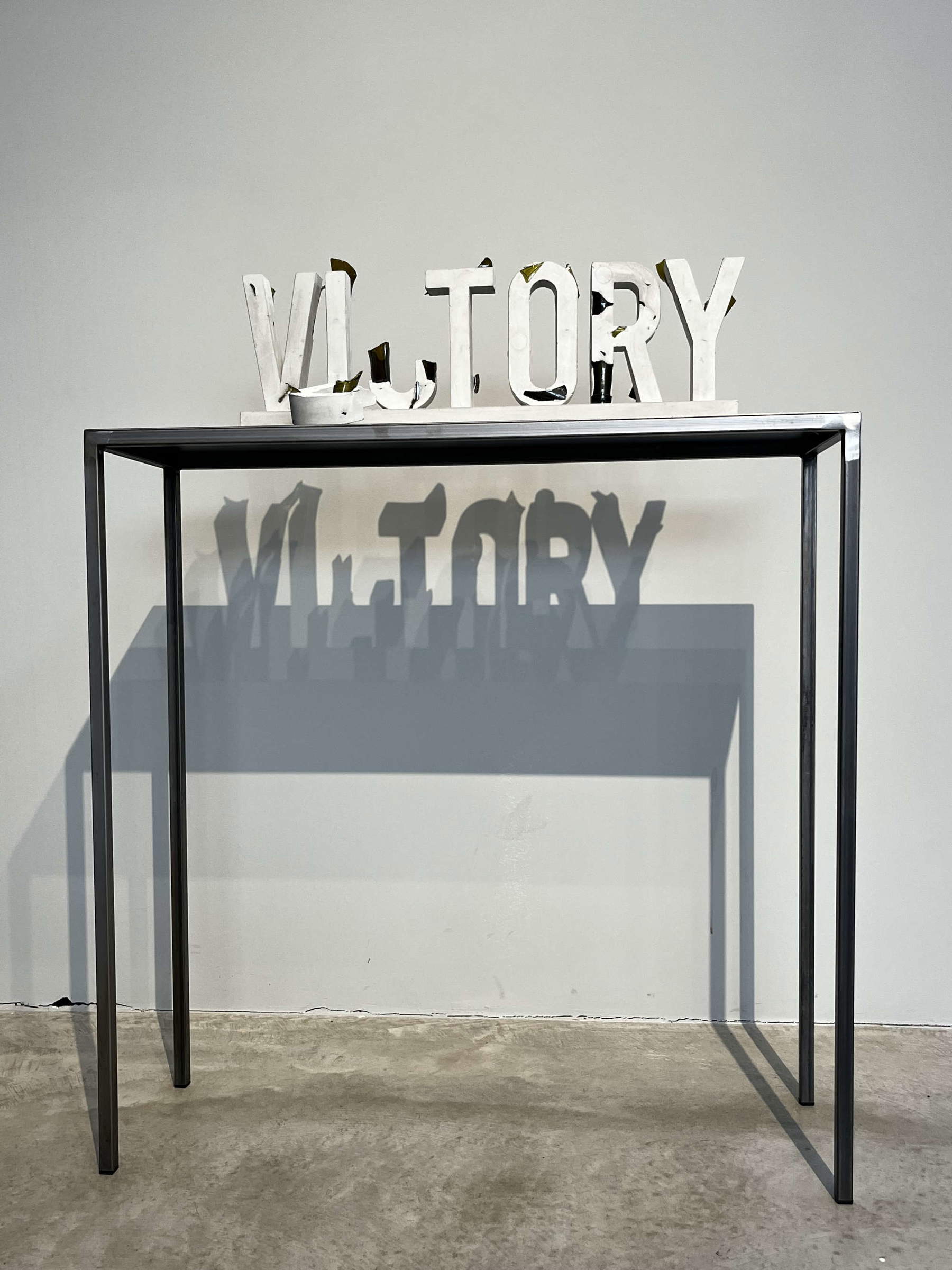

Precariousness is my mantra, if the ground doesn’t collapse under my feet, I move to a seismic location. The place where you are born and where you have spent part of your life marks the way you perceive things. I was born in Catania, lived most of my existence at the foot of an active Volcano, Mount Etna, and in the summer, since I turned one, I spend a few months at Vulcano in the Aeolian Islands where I have a small house. Surrounded by sulfur, perennial sandfalls related to the volcano’s explosions, I feel that the world below is constantly changing, as if nothing is ever defined in its form. Do you understand how geological conformation can fuel my creative processes? In the recent exhibition Crossing the line, at Villa Rospigliosi in Prato, I made a floor of concrete tiles resting on broken bottle necks of different heights, in this way each individual piece has its own inclination and height, placing them side by side the surface is uneven it looks as if something has happened in the part below, similar to a seismic movement, or the explosion of something. I also placed spotlights underneath the floor, I liked to think that the surface of this work looks as if it is suspended, as if a life is hiding, sprouting from this destruction. I don’t think any of my works are in the best static health, they have all been subjected, as I have, to hard tests of survival. They are strong though, expressing that vulnerability but also pride in standing.

Often your work seems to be based on the logic of contrast: attraction, repulsion-sensual, edgy-strong, fragile-is this a dimension in which you recognize yourself?

I titled my latest monographic catalog/book Strong and Fragile. In the edition, I published only my latest works, dividing them by materials. I believe that the use of one material rather than another depends, personally, precisely on its ability to represent something and be another. Glass is fragile, but if you break a bottle the neck can turn into a weapon, improper, dangerous, transparent, sharp. I have stacked thousands of bottle necks in my works. At the Brussels Central, I exhibited a work, Glass Gate, in which thousands of bottle necks create like an impassable wall of glass, interrupted only by a mark across it. Lights radiate the shapes onto the surrounding walls creating a pattern similar to an intricate forest/prison. This is proof that beauty can be in anything, even in a banal bottleneck. Pottery is very fragile and I take it to the extreme of its plastic resistance during explosions but it is also true that the oldest historical artifacts of the civilizations that preceded us are made of pottery, they have been there for centuries and are irreducible, they will withstand anything.

You often use video in your works either to document your performances or as a medium with its own autonomy. Are you interested in the dimension of storytelling in your work?

Storytelling is not basic in my work. I use video to document an action. I am interested in stopping the process of transformation of the subject of my performance. For example in “Explosions,” I construct scenes of family life and then explode objects and later reconstruct them. It is not really a narrative, it is a life flow. In a gallery or inside a museum, the work is displayed in such a way that next to the reconstruction of the set there is a projection of the video showing the scene before while and after the explosion, in an obsessive repetition of construction and destruction. Basically the genesis of the human being.

What importance does the space-time dimension have for you ?

I wouldn’t know how to answer that, I mean it’s not that important and so I’ll pass.

Are you interested in the fetishist dimension in the objects you use?

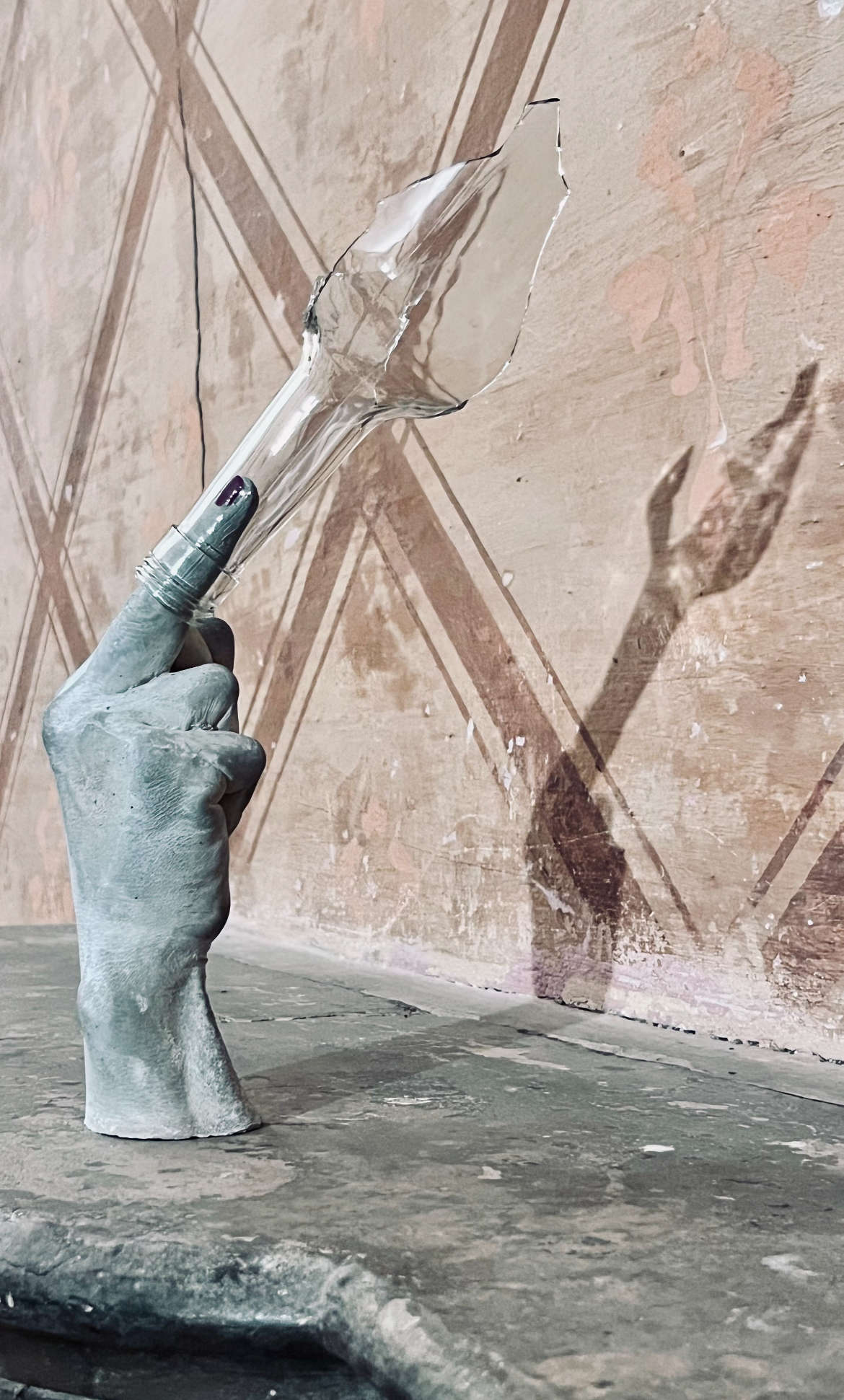

Fetishism in its murkiest sense has to do with the sexual component, which is nonexistent in my work, so I would say no. Then if we want to see the religious aspect of fetishism, I still answer no, I am not religious. I do not charge the object with particular personal importance but with more universal values that belong to everyone. I have often used the cast of my hands, but I think it represents the most mobile and gestural part of our body, I see it as something that is part of the world of making and so I interpret it in irreverent and often provocative ways as in Nice to meet you, elegant fireplace sculpture.

Where did the idea for Victorycome from , a work you have been carrying on for several years already with different declinations and how has it developed over time?

Victory was born in 2015, on TV I see a scene: a jihadist towered over a broken column in the temple of Palmyra and holds a hand up in victory. This word became iconic for me, I declined it in sculptural form with different materials and even imprinted on velvets depicting scenes of dubious victory made by burning the signs with an electric soldering iron. From the earliest marble sculptures in which I would break the letters with hammer blows and then rearrange them to the large concrete inscription in a private park, through the wall sculpture in which the word victory is written backwards with bottle necks.

You have been making frequent use of broken bottle necks for some time now: where do these objects come from in your work?

A bottle is just a glass container, but if you try to break it you will always be left holding only the neck, which immediately brings you back to urban guerrilla warfare, the weapon of defense and attack. Then you look at the broken necks and see the beauty given by the transparency and coloration of the glass, the different facets, the sharp points. Even this very poor object, when stacked in long columns, becomes threatening and attractive. I have been using bottle necks for several years, most recently making a long staircase, six meters long, Stairway to heaven, an impassable ascent.

You often happened to use ceramics :what attracts you to this material?

I think it’s its plasticity when it’s still raw. I have never modeled clay, I use this material often in casting, as in FIST, where several copies of my fist explode, again each hand opens or destroys in a different way, to become a weapon in turn. I placed my exploded fists on long sticks used for farming and burned the surface to make them more durable. In Gold Heel, the impressions of my punches and kicks are fixed on the cool, soft surface of a punching bag, with which I fight during a performance in which I wear gold high heels. The performance ends the moment I slip one shoe off and stick it into the bag.

Do you think art still has its sacredness?

It is the relationship the artist has with his creations that has its sacredness, the euphoria of thought as soon as the vision happens, the artist’s persistence in giving it form, the tension between the thought and what the work becomes, what it becomes and what it could still become, the birth of other works that follow it. This is sacred. When it comes out of the studio it takes on other aspects, as if it goes off with the gaze of others, it loses that private contact that there is between the begetter and the begotten, it becomes something else and goes its own way. I look at my works with detachment, I cannot love them as in the moment of birth, I have to leave them independent to have a contact with other that will be.

When there is no one watching it does the artwork exist in your opinion?

For me it always exists, it is there, it is in me.

Where do you place yourself in relation to your work?

I don’t think I can place myself above or below, distant or near, maybe within.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.