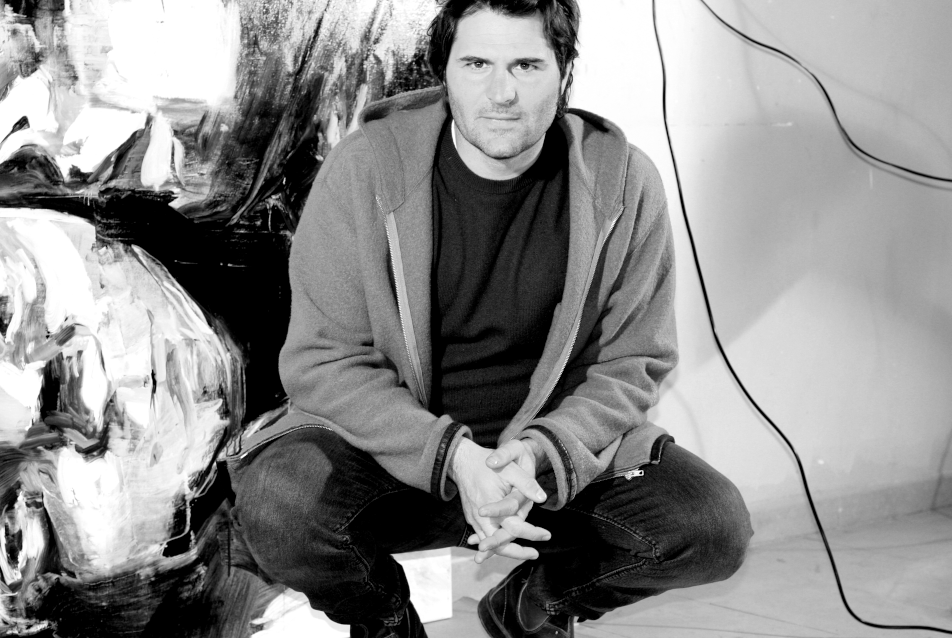

Born in Milan in 1978, Paolo Maggis is one of the most interesting Italian artists of his generation. He studied at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts between 1996 and 2000, then moved in 2005 to Berlin and in 2008 to Barcelona, where he still lives and works. His art, strong, expressive, energetic, with original solutions that combine abstract and figurative, communicates great vitality and brings out the most intimate motivations for which a human being is driven to produce art. We spoke with him about his works, his thoughts on art, and his future plans. The interview is edited by Ilaria Baratta.

|

| Paolo Maggis |

IB. I noticed that in your latest works there is always contact between the subjects depicted: affectionate, loving contact between mother and child, and also violent contact. It is a theme that especially in this time of pandemic and physical distancing becomes very significant and topical. So I ask you if your latest paintings arise precisely from the current situation and this need for contact that we have.

PM. Certainly this situation of isolation has a great impact: the most human gesture of all that is contact, which has always been present in my work, somehow becomes the subject again in an overbearing way. I have always worked on the interaction between subjects and bodies, so after a phase in which I had moved away from form because I needed on a pictorial level to understand the meaning of each brushstroke, I felt the need to return through the sign of painting to reconstruct an image. So I resumed a narrative, an iconography, related to the body and the relationship between people that is what I had started from. For me it is more of a return to the origin than a research related to a current situation that obviously affects, however I think the affect is a side effect: many times it is more what people see within a specific choice rather than a conscious and lucid decision. Returning to form through the architectural construction of bodies, which contact creates psychological reactions among the subjects and also, above all, for those who see them, was an artistic necessity.

|

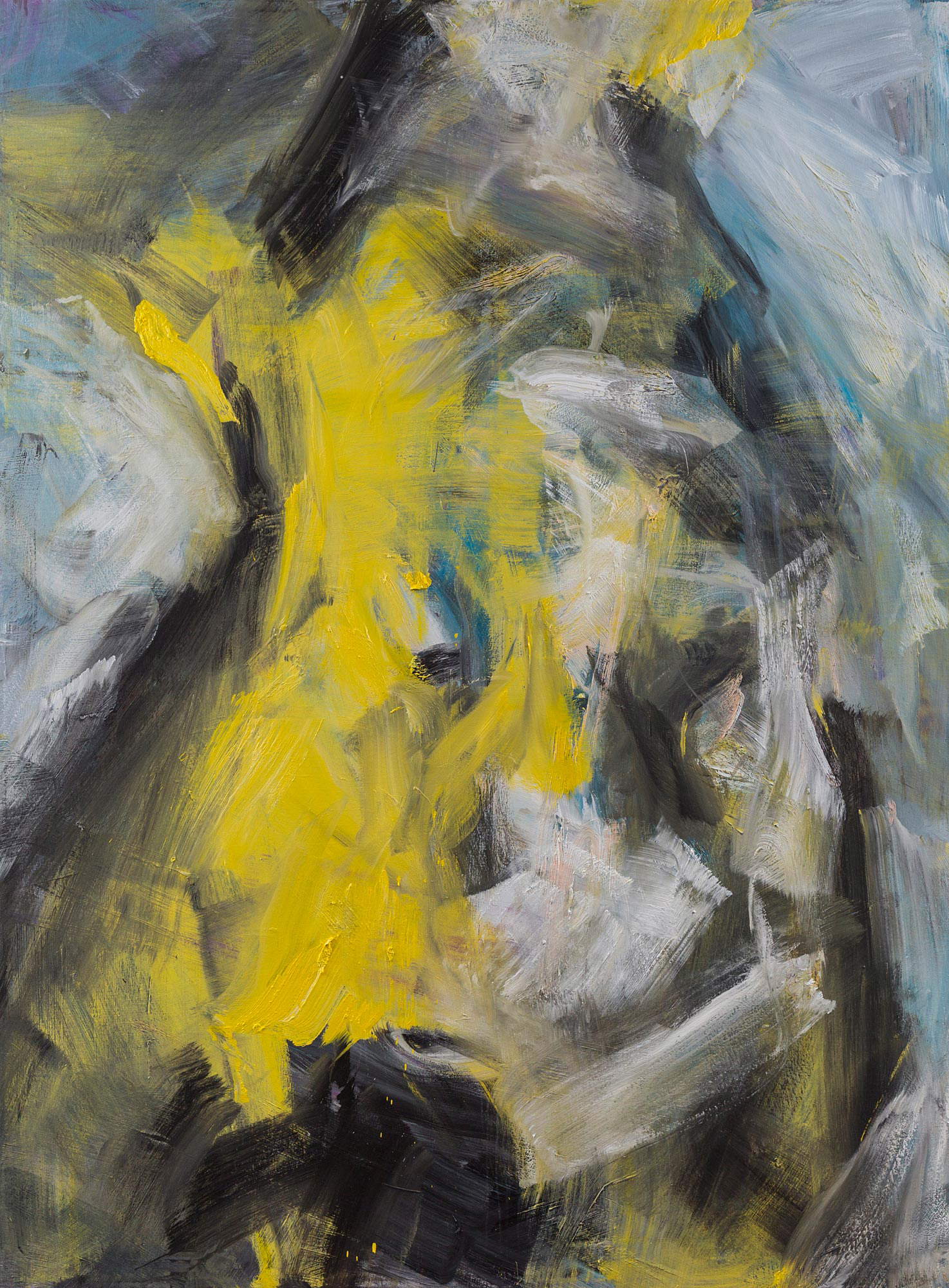

| Paolo Maggis, Keep me with you (2020; 170 x 130 cm) |

|

| Paolo Maggis, The secret (2020; 110 x 80 cm) |

Your latest works move far away from the more properly abstract: I noticed this change from 2014-2015... What led you to this shift towards more figurative art?

I think really the painting itself. In 2015 I realized that there was a problem in my figurative work: the subject matter was more important than the act of painting; the painting sometimes did not have in every mark, in every stroke, in every brushstroke, that intentionality that it actually had to have. At a certain point I felt that it was fundamental that every gesture, every action that I made on the canvas was fundamental, not a formal and gestural correctness that never interested me, but that it was the result of a choice and a specific conscious action. So when I saw that the brushstroke was beginning to follow that intention, I sensed that I could try to take back the image, give a shape back to that painting that was getting further and further away from the subject. In fact, for that kind of research I needed the close-up, that is, I needed to take details and magnify them to the limit of abstraction by letting my body express itself through brushstroke and intention.

In these last works I wanted to seek a balance, after all, my research has always been based on finding a balance between form and content. I always thought that the truth of a thing did not depend on its narrative aspect, but on how it was said: a child who says “Mommy I love you” expresses such a great truth that it will continue to be true and emotional in its eternal externalization because the truth does not lie in the sum of the four words, but in the child’s need to express them. I sought and seek in painting that consciousness of gesture that somehow can give truth to the form itself; a point of balance in which the painting is not secondary, but the soul of the subject itself.

Despite your academic training at Brera, you chose to make abstract art that breaks free from formal correctness and the limits imposed by convention. Why did you feel this need to break free from formal correctness, to step outside the limits?

Because basically I realized that it did not belong to me. I went to a very classical academy and an art high school that was also classical. These years of schooling taught me how to perfectly paint or draw a face, a body, an image, but I felt that there was no consonance between this knowledge and what I was as a person and it did not respond to the expressive need that shakes me. I had to make the stroke and gesture become foundations of my work so that I could better express what I feel and experience in my relationship with reality.

|

| Paolo Maggis, Storm (2015; 89 x 116 cm) |

|

| Paolo Maggis, H1747 (2017; 160 x 180 cm) |

His works are strongly expressive and energetic, and above all this bursting expressiveness is rendered through color, with large and dense brushstrokes clearly visible and marked on the canvas. Thus, color becomes the fundamental element of His art. Why is color the protagonist in His works and what does He intend to signify through color?

For me, color is life. When I paint I don’t choose color, it is my body that chooses it: many times I don’t even look at the tube I pick up. Color is life, passion. I lived in Berlin and then in Leipzig, and in those cities you have the feeling that color does not exist, you experience the lack of light: everything is gray even when it is sunny. Light and color bring things to life, catapult the subject into the realm of life. The choice of color is linked to this need for vital expression, which perhaps deviates from a more intellectualistic vision or linked to conceptual choices in contemporary art, but which is part of my desire. Through color I live.

You define your paintings as “the result of a struggle of the pictorial matter that breaks free from the limits imposed by the subject”... even in some “the brushstrokes struggle for survival.” There is a kind of philosophy then within your works....

I don’t know whether to call it philosophy, because philosophy is rational, it reflects on life through thought. Mine is not just reflection on life, I see it more as my body’s attempt to express itself in relationship with the world. I think our brain is a crazy machine that contains much more than what our own reason can conceive. At a certain point I realized that I had to trust the brain and the infinite possibilities it can generate, outside of my temptation to contain it: painting struggles with the subject because really everything you do within a painting is a life choice. The brushstrokes destroy the subject and the subject tries to resist in an obvious contradiction that is simply part of a process totally beyond my ability to contain it. Why do I love making art? Because it is the miracle of seeing that your body, in the unitary sense of the term, following an order that is not in your logic and perhaps not even in your subconscious, creates an image in spite of you, beyond your preconceived idea; the moment you introduce within that creative act thought, you risk killing the result. When I create there is a moment when I lose consciousness of what I am doing: as if there is a higher or other consciousness whereby the brushstrokes flow, the subject is built up or deconstructed, but, in that moment I am not thinking, I am just me, free.

Even in the most abstract paintings, Your art starts from reality. Can you explain this relationship with reality?

I think all art is abstract because all art is an abstraction operation. When I take a subject and take it out of a context I am making a gesture of abstraction condition that not even the most formal painting is able to get rid of. On the other hand we are not able to live without reality fundamentally because this is the only tool we have been given to know, which is why I believe that basically abstract and figurative art share the same mother. When an artist paints the canvas a color (I give the example of Yves Klein) that color is something, it is a part of reality. Personally, even in my most abstract paintings I have always started from an idea of tangible form or one that I had in mind, from a formal architecture that could be described through lines and geometries so much so that I am convinced that even the most abstract painting always starts from something that has been seen and has settled in the mind seat in which it has found a place to live and then flourish. All I do is take a piece of reality and transport it to the canvas.

|

| Paolo Maggis, H1744 (2017; 147 x 195 cm) |

|

| Paolo Maggis, H1805 (2018; 83 x 92 cm) |

What are your models for your art? If you are inspired by any artists...

Obviously there are a lot of references in my work as I imagine is the case with most artists. We have all studied, experienced and felt art, and attended museums: the things we see get stored in our brains and then resurface. As I said, of references I have many that span the entire course of art history. One artist I’ve always loved very much is Titian, especially in the last phase of his work; I love Vedova’s work, which is much more abstract and contemporary; I like a lot of great figuration from Masaccio to David Hockney; however, I have a very hard time identifying elements in concrete. I recognize that in my work there is a centripetal vision, where all the elements converge toward a center, and I can also recognize a deeply Italian root pictorially. I proceed by large brushstrokes, which if at the beginning of my research were juxtaposed are now sedimented creating a surface structured in layers . Therefore, they are no longer isolated colors, but the color is presented to the user vibrant thanks to the sum of more or less transparent superimpositions as was the case with glazing in seventeenth-century painting.

You have stated, “Yes, art, let’s call it utopia, can change the world.” What do you mean by this statement? What role does art play for you?

I was referring to the arts in general, whether it is art, philosophy or literature. I think art is that magic, that miracle that, somehow as it happened to me, can change your life, your view of things, can make you think differently. Art, because of its ability to generate thought, but also emotions, feelings, subconscious, has a driving force by which our brain and our person can change. This has happened to me many times in seeing works or reading books, poems many of which I did not even understand or consider sufficiently at first, but without realizing it have become imprinted in my memory. Over time these things read and seen somehow moved me physically from one position to another or from a myopic view to a clearer and broader one. I believe that art can change the world if it is experienced as a relationship and if it is experienced in relation to life, it can change people’s heads and change the point of view with which they come back to face reality. Art can change the world in the human and experiential sense of the word: that spoken word, that seen painting can make you rediscover life. In the works you see, you experience something very great that is able to trigger a desire to take hold, to return to experience that beauty, that greatness, and that desire drives you to take actions that change you forever.

You have lived in Berlin and now live and work in Barcelona. How do you see the current situation of contemporary art in other European countries compared to Italy?

Premising that Germany and Spain are very very different situations and have little to do with the Italian situation, I think that Italian art is suffering a lot right now. Both at the institutional level and at the general cultural level, there is a total lack of approach to art. In Germany people are accustomed to visiting museums that they go to without complexes bringing including their children, while in Italy, and in Spain even more so, there is much less frequentation of art rooms. This evidently generates a whole series of consequences whereby art is in danger of becoming both at the level of its production and at the level of its fruition, a specific language disconnected from the world, absolutely antidemocratic, that is, outside the possibility of everyone having access to it, and on the other hand incapable of generating. If art is generation of thought, generation of beauty, and also of criticism on life, the moment its interest and exercise is not stimulated in schools and in everyday family life, its power is completely annihilated. In Germany everyone accesses museums, people are used to going to museums, schools take kids to see museums, which is not the case in Spain and in Italy little and sporadically. The problem with art, like all things related to the cultural sphere after all, is that it is not enough to see it once to be understood but it needs constancy and dedication. It is very difficult that by seeing one work a year a person can understand what art is, it needs frequentation, which in Italy has never been stimulated, neither at the school nor educational level. Today we experience a disconnect between art and life, as if art were an unnecessary antagonist to the cognitive path of being. If from a certain point of view contemporary art now speaks to no one but itself because it is aseptic, hermetic, you see it and cannot understand it unless you have read a whole series of volumes and writings that justify it, on the other hand the public, has stopped looking for it therefore looking at it and asking for anything. Art precisely because of its being visual needs to be looked at and looking takes time and love.

What are your future plans?

Future plans in this situation are a bit volatile, smoky, however these days the Close-Up exhibition opens in Milan where I would have liked to be present. For a long time I would like to return to Italy with my studio. Surely there will be other events both private and public, but it is all still very confusing. Right now we are living in uncertainty and everything is stuck or moving tentatively. Even if you want to do, you struggle to do. But we continue: art will never end.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.