Paestum, a participatory and inclusive place to give a strong signal to the south. Director Gabriel Zuchtriegel speaks.

The Paestum Archaeological Park, under the direction of Gabriel Zuchtriegel, an archaeologist born in 1981, has undergone major transformations and has become a very active site. There have been many innovations, from the opening of the deposits to maintenance plans, through exhibitions and many initiatives, some of them unique. Zuchtriegel’s term will expire next year, and since the Paestum Park is one of the places most affected by the autonomy established with the reform in 2015, we interviewed the director to understand what principles have animated the many actions undertaken by the Park during these four years. The interview is by Federico Giannini, editor in chief of Finestre Sull’Arte.

|

| Gabriel Zuchtriegel |

FG. Director Zuchtriegel, your management of the Paestum Archaeological Park has been very active indeed. Excavations have been going on relentlessly, there have been exhibitions, special initiatives, openings to international relations, interesting experiments and much more. Soon your term will expire: so we would like to know if you can take stock of your management.

GZ. We have started many things and many are yet to be finished. The first essential point is that of research: the park developed its own scientific research program, which we then carried on by also collaborating with universities and institutions. We were the first state museum in Italy to do an excavation, we even raised funds for it, and I think this is very important because research is the real heart of our activity, which is not only to tell what we already know, but also to tell about research as a method, questions, dubbî. The second major theme is that of accessibility, inclusion, openness to the territory: meanwhile, Paestum guarantees routes without architectural barriers (we have the first Greek temple still standing where you can enter in a wheelchair, we have made a route for blind people with tactile models, and now we also have a route for autistic people), and the very opening of the deposits, which are now open every afternoon, is a sign of openness and sharing. We do our research and our work, but we also want to share the behind-the-scenes, in fact the initiative of the repositories is called Museum Behind the Scenes: we also want to tell people about the whole process of archaeology and excavation to make them aware of these issues. Inclusion, however, also means affordability: there are concessions (we have introduced free admission every Thursday evening as part of the increase in free admission wanted by Minister Bonisoli), there are so many initiatives and collaborations with the territory, with associations and foundations, and above all we finally have, for a little over a year, the association of the friends of Paestum (modeled on what other museums are already doing especially in the north and also in other countries: I am thinking for example of associations such as the Friends Groups of the Metropolitan Museum or the Freundeskreis of German museums), that is, a group of people from the local area and even beyond (because there are people who also come from further afield), who support our activity. And then I would also like to mention the annual ticket at a symbolic cost, one euro more than the normal ticket, which was introduced with a view to encouraging the use of the museum not as a singular and punctual event but as a point of reference: that is, visitors know that by paying that extra euro they can come back every day of the year. So the theme is to make the museum not only a place of culture, history, and archaeology (because this of course always is), but also a point of reference, a kind of cultural and social center for the area, and to create synergies with all the excellence that is in the area. Finally, the third essential point is conservation, restoration: in the past the system of allocations and management did not allow in the Paestum site a continuous maintenance and also a monitoring of what needed to be done. Now we have resumed the maintenance and restoration plan for the temples, which had been suspended about ten years ago due to lack of funds, we have also started a major restoration and maintenance project for the walls of Paestum thanks to European funding, and, among other activities, we are starting a routine maintenance plan for the archaeological area, which may seem like a trivial thing, but those who know a little bit about the situation know that the real key to successful change is to move from managing emergencies, where we then always have to invest very large sums, to ordinary maintenance that is done every year, investing and thus avoiding the point where there is an emergency, the collapse, the degradation that make it necessary to remedy with even very substantial resources. So this is absolutely strategic, as is also, for example, the anti-seismic monitoring of the Temple of Neptune (a project for which we have raised 110,000 euros of funds also from private individuals), which involves continuous monitoring of the monument, with advanced technology, in real time, collecting data that arrive in a control unit and that will then be available for consultation on the web through open data and accessibility. For us, conservation and restoration are fundamental aspects.

|

| Paestum from above |

|

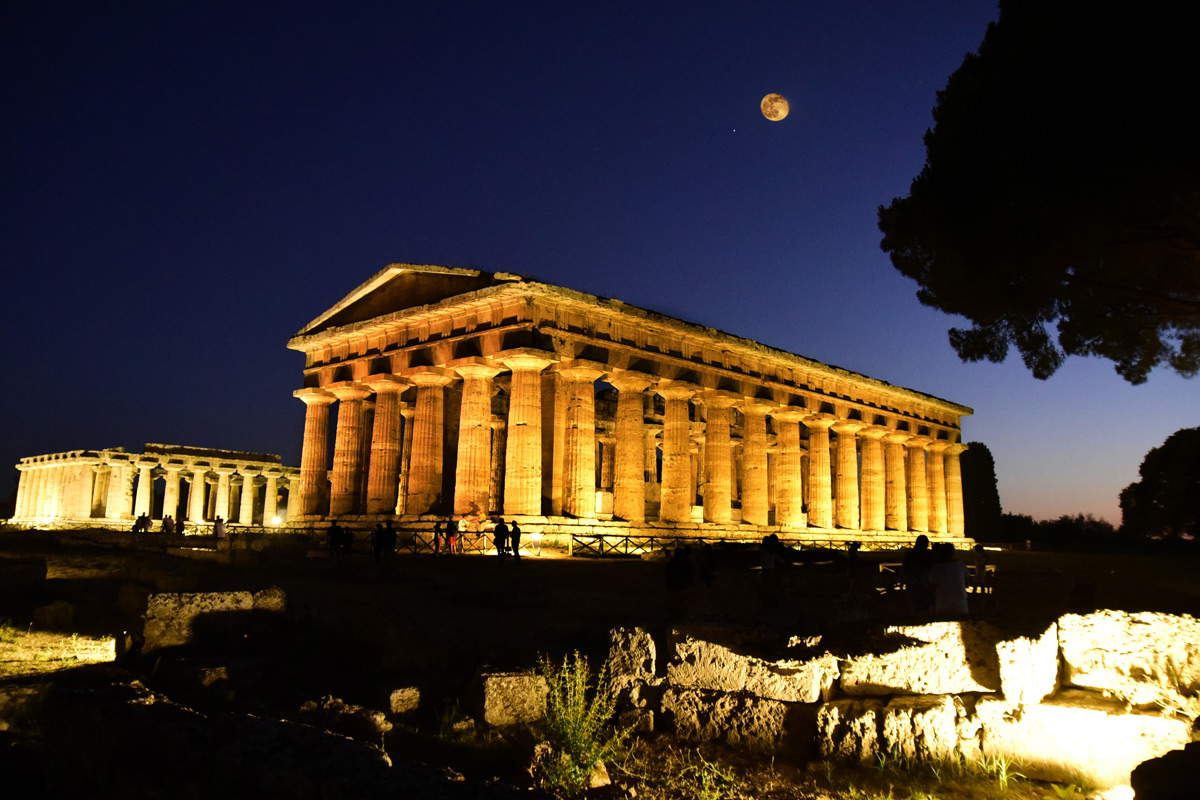

| Paestum at night |

An interesting fact about your management, which you mentioned in reference to the plan for the Temple of Neptune, is precisely the raising of funds from private individuals. What is your approach in this regard?

We have started a path with businesses in the same vein of inclusion and dialogue. And in three years we have raised about 300,000 euros in donations and sponsorships, 170,000 of which in the last 12 months alone: this is a very strong signal in a south where we started from scratch, because there was no such tradition and culture. We have found a response, especially on the ground, from private individuals who support us, and I emphasize that from the beginning we have approached this issue not as a gimmick to fill purely economic gaps, but as one form, among others, of citizen and business participation in the management and revitalization of cultural assets. Even this fundraising activity for us is a way of entering into dialogue, it does not end with the economic transaction and the transfer, but this also creates links between people, the realities on the ground and cultural heritage.

And always talking about accessibility, we can say that the Archaeological Museum of Paestum was the first to open the doors of the deposits permanently to the public. That of deposits is one of the main issues in the current debate around museums, because discussions about accessibility to heritage also pass through the display of what is preserved in deposits: in your opinion, can there be a formula for linking museum and deposits and, above all, for engaging in a serious discussion on the subject, given that deposits are often talked about out of hand?

When we opened the repositories on a permanent basis, we thought of allowing everyone to enjoy these spaces as well, which is a bit tricky: it is not easy because the public visits a real repository, and not a repository exhibition or a repository-museum. So visitors come to the repositories seeing restorers sometimes doing live operations, objects come in and out for exhibitions, and basically you really get to see the museum behind the scenes. We have managed, through a collaboration with the Cilento for all association, to make it accessible. For the rest, repositories are a very hot topic, especially in archaeology, because they are archives that are constantly growing: every excavation that is done, even emergency excavations that occur in the area for new construction or building activity, increase the repository. Of course, inside the repositories it happens to find masterpieces, but there are also thousands of fragments of ceramics, pottery or the like: a large amount of materials. That represented by the deposits is also a great challenge for management and research, and in our experience one of the problems is that the deposits are in a very delicate state. The museum is visitable and has to be kept in a decent state otherwise it is immediately noticeable, and often in the repositories the situation, on the contrary, is very difficult: however, by making the repository usable as we have done, as a part of the path, you also go and affect the management of the repository. Put concretely, I have never seen these depots of ours as neat, as clean, as arranged as they are now that they are visitable, because we cannot afford to present ourselves in a way that is not absolutely up to par and perfect. This also benefits the other users of the repositories (the researchers, the archaeologists) and therefore triggers a virtuous circle: the accessibility and visibility of these places also contribute to their management, preservation, and arrangement.

|

| The Temple of Neptune |

|

| Paestum Archaeological Museum, the Mario Napoli Room |

|

| The most famous of the Tomb of the Diver’s slabs. |

Let’s keep talking about inclusion: You mentioned earlier that Paestum also wants to tell the public about “research as a method.” In this sense, one of the most significant exhibitions held during your administration was the one dedicated to the Tomb of the Diver (The Invisible Image. The Tomb of the Diver). In the presentation of the exhibition it was stated that the exhibition was actually an “an ’anti-exhibition’ that wants to ask questions, putting visitors in a position to participate in the debate and grasp the reasons behind it.” Now, the thought that comes most naturally is that it is very difficult to get visitors to participate in a debate around a work, since not all the public is given the tools to take part in such a discussion: so what was the point of the operation?

Isn’t doubt more complex than clarity, and we have tried to prove this hypothesis by even making a guide to the exhibition for children as well, entitled Dionysus, the god in hiding. Our work, as art historians, archaeologists or architects, is full of doubts, ambiguities, uncertainties, choices, stances, ideological issues that also affect the reading of the past. So our task, at least in my opinion, is to tell that as well. Because if we pretend that we have found the solutions to everything, then we don’t tell the real story, but we tell a construction, a fiction that doesn’t even convey what for me is the fascination of our work, which is not only the answers, but it’s also the questions, the discussions, the debates. And of course most people think it’s a complex and difficult enough thing. I, however, do not have that impression. The exhibition certainly was ambitious even in the basic concept that we chose, but it was an unexpected success, followed even in important magazines and newspapers abroad, and this pleased us very much. However, the basic principle is very simple: I do not tell the absolute truth, but I also tell the method of arriving at a scientific hypothesis, and then I also say that this is, indeed, a hypothesis, and like this there are also others. I believe that if we think that the public expects apodictic or absolute truths from us we make a glaring mistake, because often doubt, debate, discussion, and contradiction are even more interesting even to the layman.

I understand, however, that it was still a matter of “passive” participation on the part of the audience, it is not that the audience could actually participate in the debate: they were, however, being put in a position to understand the research developments around a work.

We had a lot of discussion on this, and the same applies to the excavation. On a daily but also weekly basis we do updates on social media, videos that we share on the web that tell the story of the excavation, guided tours conducted by the archaeologists working in the excavation, just with a view to sharing doubt and uncertainty, and this has caused a lot of discussion among colleagues because there is still a very ingrained view that first you have to survey the data, study it in its entirety, discuss it only among insiders, come to a conclusion, and then eventually announce this conclusion, this “established truth,” to the “people,” so to speak. The concept of dissemination: I hold a process of knowledge and research, and at the end of this process is the distribution, the dissemination to the world of this knowledge to those who are not able to understand the method. Ours is another approach, it is that of public archaeology, of sharing that involves participation and sharing from the very beginning. I think we don’t lose anything if we admit that in all areas we make assumptions, which are sometimes wrong, that we then find another piece of data that points in another direction... and that’s really the fascination of our work.

Changing the subject, we can say that the Paestum Park has hosted many initiatives, of various kinds, some of them even unusual for a museum. In Paestum we have seen concerts (on one occasion She also played the piano), we have seen film scenes filmed, we have seen solidarity dinners and much more. In short, it can be said that Paestum is one of the most active sites: considering, then, the activities that have taken place during your management, what is the image that you wanted to give of the museum?

The image is that of a participatory and inclusive place not only in storytelling, but also in research, in management, in protection. It is that of a transparency of our actions as well, it is the image of a liveliness, that is, of the contemporary nature of the museum. What we do has a direct link to contemporaneity. Each generation constructs its own past, not because the past changes, not because the data change (which are always the same), but because the questions, perspectives, methods change, and therefore the past never remains the same. The museum, together with other institutions such as the university or cultural associations, all of which are involved in one way or another, contributes to the reinterpretation and actualization of the past, which is an ongoing process that takes place even without our will, but which is essential to the culture of memory. What we are, we are based on that image of our path understood as humanity and community in the past, so it also orients us toward the future.

|

| Gabriel Zuchtriegel at the piano |

We talked earlier about research and the fact that Paestum focuses a lot on research. But in your opinion, is Italy doing enough to ensure that museums are put in the best possible position to do research?

In the public discussion, the issue of research has been greatly underestimated. However, in the reform of cultural heritage it is present: museums have in their institutional tasks also research, and I am of the opinion (but people like Giovanni Pinna and Lanfranco Binni, who wrote a book entitled Il Museo. History and Functions of a Cultural Machine: we have now moved closer to what they hypothesized) that research, in the area of art history, archaeology, anthropology, is not only the domain of universities, but a plurality can benefit research. Other institutions such as museums contributing to research not to diminish the role of universities, but to create a plurality of voices, of approaches that can only benefit research, which always needs innovation and new perspectives. It is precisely with this in mind that we have invested our own resources in research, we also collaborate with Italian and foreign universities, we invite universities to do research in Paestum, and we are open, but we also have the task, as a museum and archaeological park, to do our own, not in competition with the universities, but to add a perspective and a vision that sometimes are also different, because we know that the ways of management and funding affect the choices and the universities have certain orientations, while the museum has others. This is perhaps not so much true for excavation as it is for archaeometric and collection analysis activities because there the issue of conservation also comes into play. If we can see colors on an ancient metope that you cannot see with the naked eye, then that is a great achievement for research, but for us it also raises the question of how we can preserve those remains and how we can then tell the public about them. We, when we do research, also have this perspective in mind, that of preserving and passing on this knowledge to the public... which, then, enriches the work. We, for example, did an exhibition together with the University of Salerno, and this I think was enriching for both parties: for the university, because we helped tell the public about their research, and for the museum, because the university made available its knowledge obtained over the years.

We gave a nod to the reform. As is well known, you are one of the directors of the new autonomous museums created with the reform of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage: after four years of work, what are your impressions of this part of the reform? Do you believe that autonomy has brought tangible benefits?

I think it is there for all to see what has been done thanks to autonomy and this is very important, not only in Paestum but also in Naples, Reggio Calabria, Taranto, Herculaneum, Villa Giulia. Not only thanks to individuals but thanks to a new management system, so it is not the fault of those who came before us that certain things were not done. I think the strengthening of the dialogue between museums and territories is also tangible.

But still in some realities the problems remain. For example, you mentioned Taranto, which still has many problems with staffing gaps, and the same happens in other realities. So in your opinion, given that the problems are there anyway, what could be the issues on which to intervene with possible future changes, also in view of the fact that a new reorganization of the Ministry is currently being studied?

The issue of personnel is certainly very important but it is not directly related to autonomy or not. It is an issue that affects everyone a little bit, especially the Superintendencies and the Museum Poles. I think Minister Bonisoli’s plan to make more hires goes in the right direction, regardless of how the individual institutes of the Ministry are then organized. The issue needs to be addressed, but this applies to any kind of organization.

Still on issues related to reform: there has been a lot of insistence on the issue of openings. You have opened to nighttime visits. There are many calls for museums to make evening openings structural, because it would be a way to bring museums closer to local audiences in particular. Yet you often find a lot of resistance when it comes to this issue. How have you guys approached it? And why is it so difficult to make evening openings stable?

It is a matter of staffing and resources. We also try to do what we can together with the Campania Region, which has made evening and night openings possible in past years. This is something to be continued, and I hope that this year, together with the Region, we will be able to guarantee these openings as well.

In conclusion, what do you see as the main challenges facing Paestum in the future?

The main challenges are the routine maintenance plan, the management of structural funds for the redevelopment of the museum, the archaeological area and the former Cirio plant (it’s 38 million euros, so a huge challenge for an administration like ours that is young and has to make a quantum leap also in financial and project management, but I’m sure we will succeed thanks also to our collaborators), and the buffer zone, that is, everything that goes around Paestum, where there is an appalling situation of degradation and abuse, which sooner or later will have to be addressed in a systematic way, because as it is now it cannot go on. Paestum is a UNESCO world heritage site, and we have to ensure that there is also a context consonant with the importance of this site.

And finally regarding your future, do you still see yourself in Paestum in the coming years?

Well maybe I should look at the stars, but I am not an astrologer.... ! I now try to finish my first term, which is still full of activities, in the best way, and then it will be up to the Ministry to make an evaluation, as I think is absolutely right. I appreciate this change: doing fixed-term terms and then proceeding with an evaluation. However, I will not be the one to make that evaluation, it would not be fair, so I am waiting to see how my performance will be judged. I will try my best, and I must emphasize that, despite all that is said about the public in Italy, upon arriving in Paestum I found a motivated, smart team of people who welcomed me very warmly and started working with great enthusiasm, including colleagues who are close to retirement. Seeing them enthusiastically espouse this project, this new path of the museum, was perhaps one of the greatest gratifications in these years, and so I hope, also for the colleagues, that Paestum in the future can continue this path, even independently of me. And finally I hope that autonomy, openness and integration with the territory will go forward.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.