by Ilaria Baratta , published on 13/07/2018

Categories: Interviews

/ Disclaimer

Nicola Samorì is one of the most celebrated and appreciated contemporary Italian artists. A painter and sculptor, in this interview he tells Ilaria Baratta about his art.

Nicola Samorì (Forlì, 1977) is one of the most interesting and celebrated contemporary Italian artists. Known for his paintings that recall the aesthetics of the seventeenth century, Samorì investigates the action of time, our relationship with the past, with museums and with art history, and the alteration that works undergo over time. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and has exhibited all over the world. Among the high points of his career were his participation in two Venice Biennales, that of the exhibition Italian Art 1968-2007. Painting in Milan (Palazzo Reale), solo shows at the MAC in Lissone, the Kunsthalle in Kiel, and the Pescheria Visual Arts Center in Pesaro. Ilaria Baratta interviewed him and Nicola Samorì told us about his art.

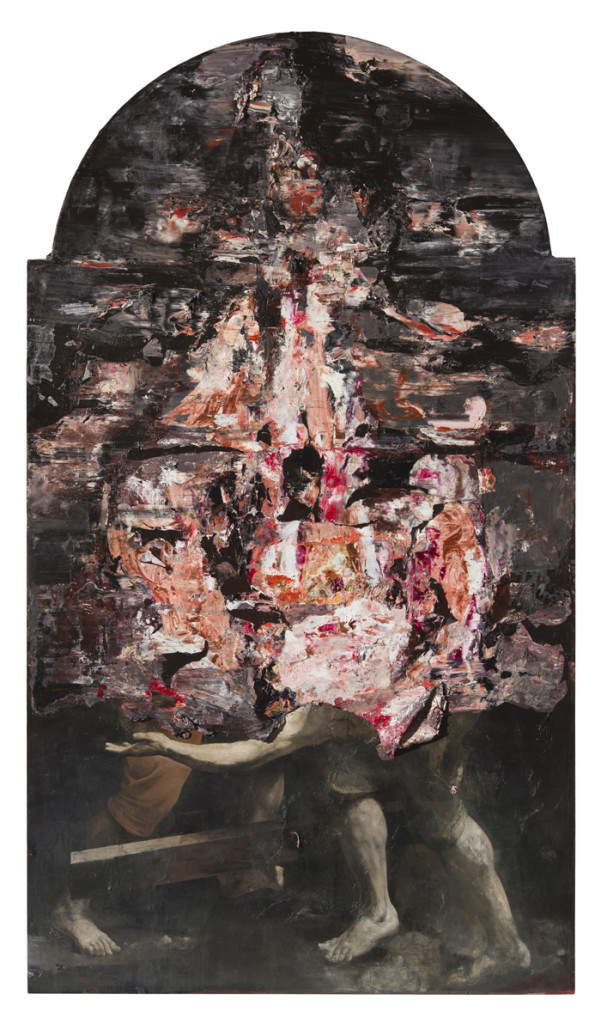

IB. In your last solo exhibition The candle to make light must consume itself, which was held from July to October 2017 at the Pescheria Visual Arts Center in Pesaro, your works dialogued with the collections of the Civic Museums of Palazzo Mosca. How and with what attitude did you engage with them? Does the title of the exhibition refer to this confrontation?

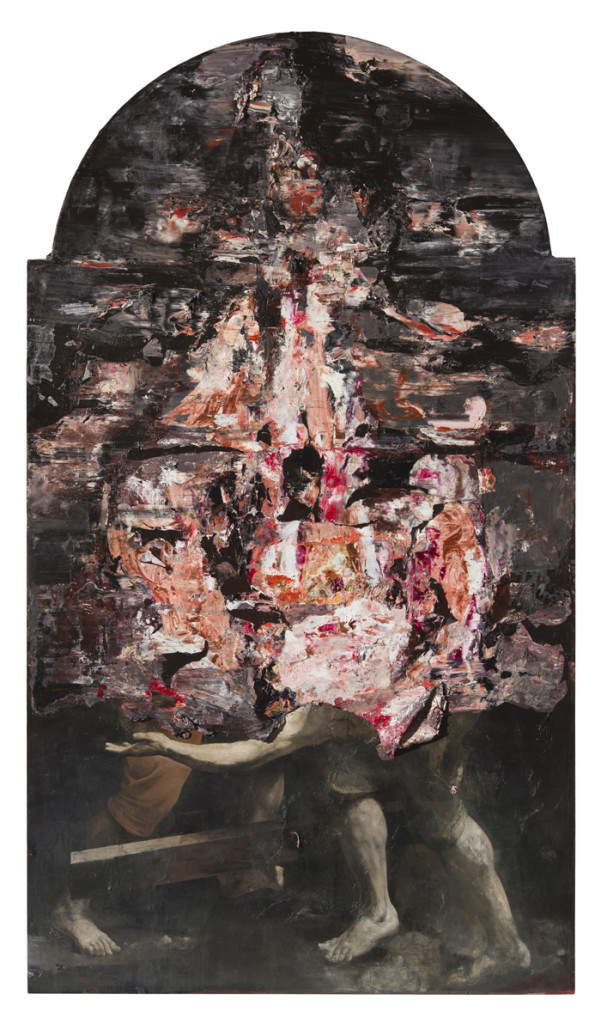

NS. I was specifically asked to include works from Pesaro’s collections, and during the first inspection, it was easy to find the key by exploiting the demon of analogy: a Christ and the Manigoldo painted by Giuseppe Maria Crespi, damaged during World War II following the destruction of a wing of Palazzo Mosca in which the painting on copper was kept. The title coincides with the last sentence attributed to St. Charles Borromeo and connects to the large vertical wood that stood in the center of the former Church of the Suffrage, Lieve legno, resembling an immense, crumbling candle.

|

| Setting up the exhibition The candle to make light must consume itself. Ph. Stefano Maniero |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Lieve legno (2017; walnut wood, 275 x 40 x 30 cm) |

|

| Giuseppe Maria Crespi, Christ and the Manigoldo (ca. 1735-1740; oil on copper, 41 x 32 cm; Pesaro, Musei Civici di Palazzo Mosca) |

And how did it compare with the works by Alberto Burri exhibited for the Gare de l’Est retrospective in December 2016? It was the first time ever that Burri’s works from the Palazzo Albizzini Foundation were placed side by side with His sculptural works and the works of Gustave Joseph Witkowski in such an unusual space as the Anatomical Theater of the University of Padua. How do you stand in relation to these important comparisons?

With a good dose of recklessness - indispensable to dare - also because I do not know any lucid ways to physically approach a work by Alberto Burri.

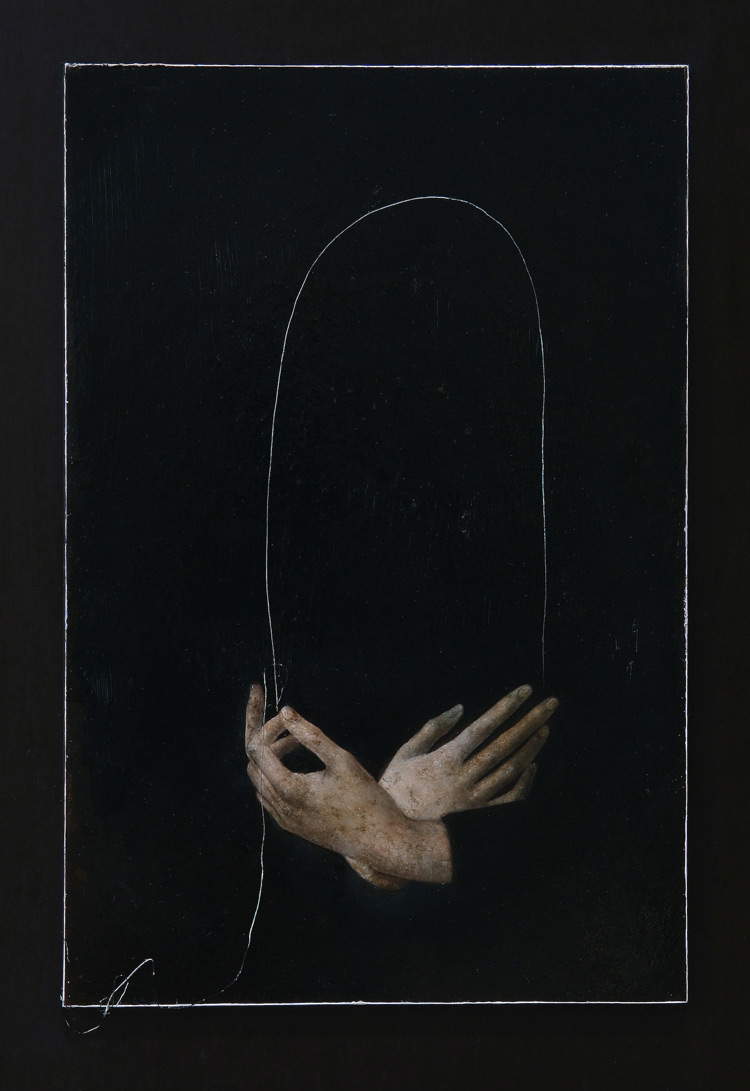

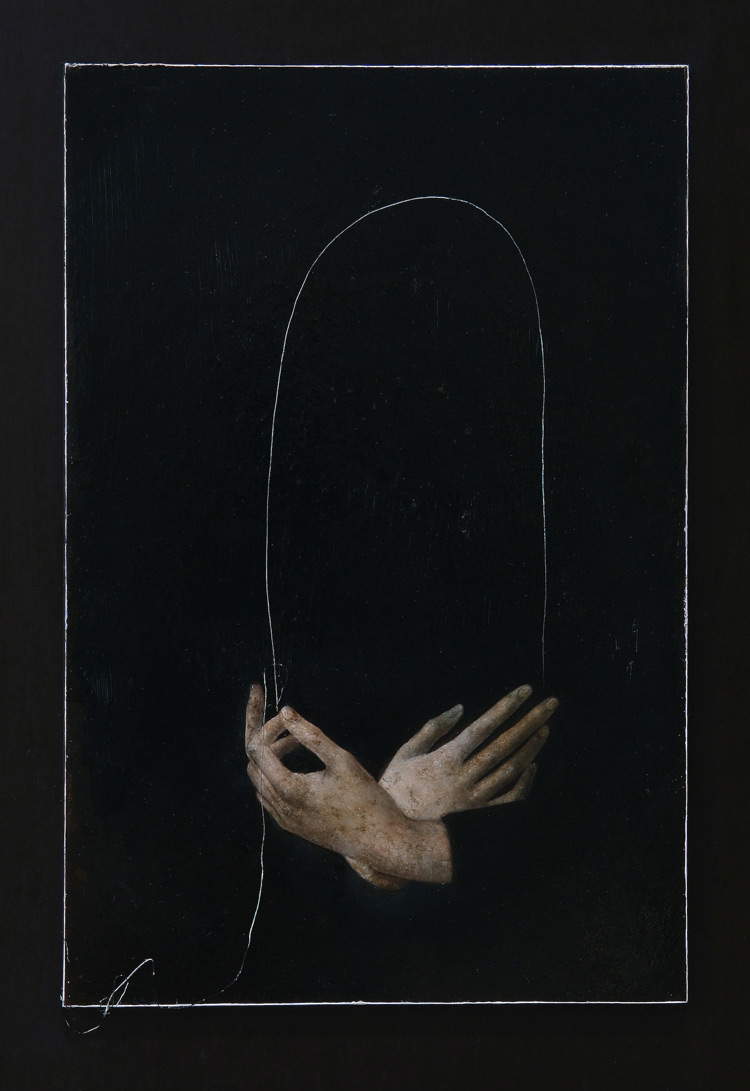

On the occasion of Your exhibition The Dialectic of the Monster in February 2010 in Milan, You stated that Your object of research is to return an unstable theater where portraits of portraits (never portrayed from life) repeatedly fail in their attempt to fulfill themselves. Indeed, most of Your works feature figures with indefinite, undelineated, almost diluted, often even nonexistent or scarred faces. What significance does it have for You to depict portraits of faceless figures? What gave rise to this distinctive trait of yours?

Overcoming the slavery of the gaze: if you tear out the eyes and part of the face from the body a myriad of new eyes gem around the abused. Even so we begin to see what happens beyond the eye sockets, shifting lattention from the complicity of gazes to the machinery of representation and all those mechanisms that the meeting of our eyes with the painted ones displaces in a dombra zone.

|

| Installation of the exhibition Gare de l’Est. Ph. Rolando Paolo Guerzoni |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Agnes (2009; oil on copper, 100 x 100 cm) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, r41 (2010; alabastrine plaster, wax, pigments, 170 x 115 x 45 cm) |

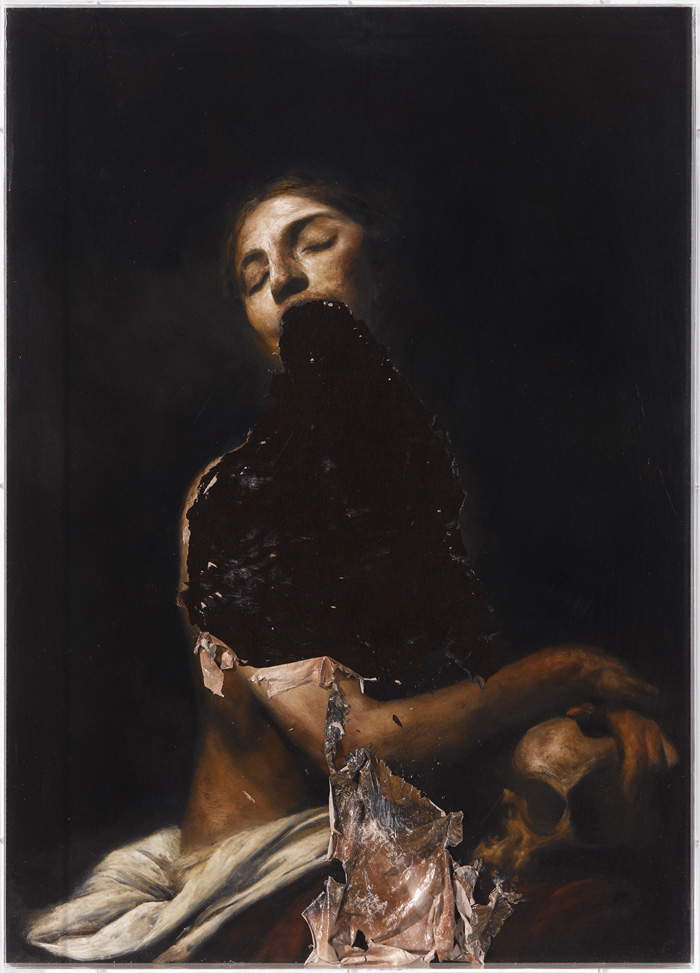

What feeling is your art moved by? Is it a gesture of anger, of rebellion, or does it take shape from a deeper feeling?

One is not always kind to what one loves. I have never rebelled against anything, nor am I angry. I try to pick up on the weariness of images in museums and in our memory, which need a catastrophe to find blood again; but defacement is never a vandalic entry into the body of forms, but rather a thoughtful expedient that insinuates a rereading by breaking the thread of the narrative.

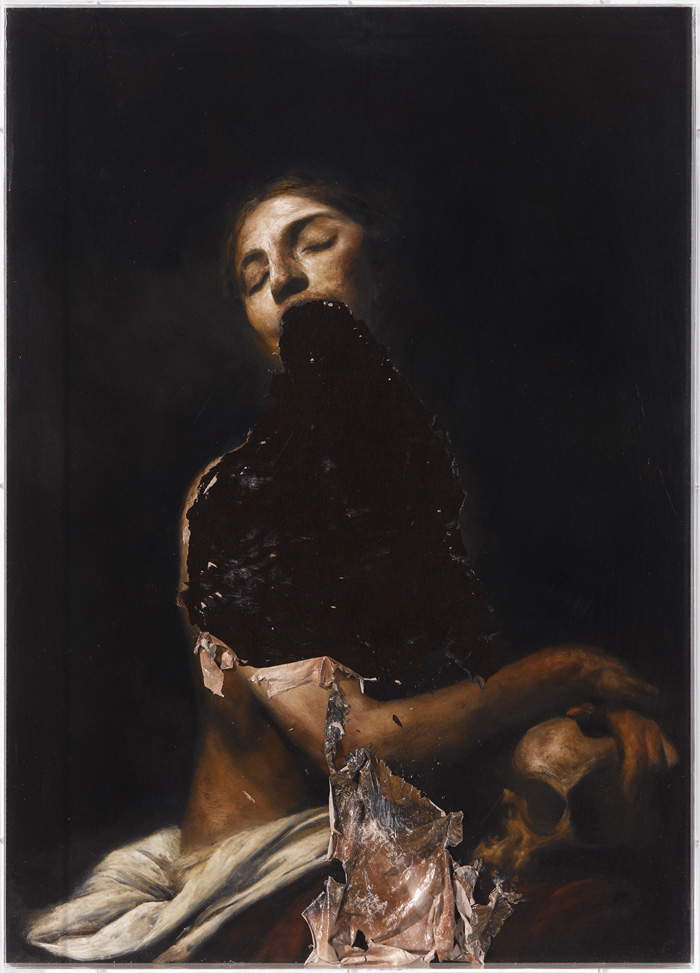

His works generally have a dark background reminiscent of the Baroque period, when the figures depicted stood out against black or dark brown backgrounds. To what extent is Your art related to the Baroque?

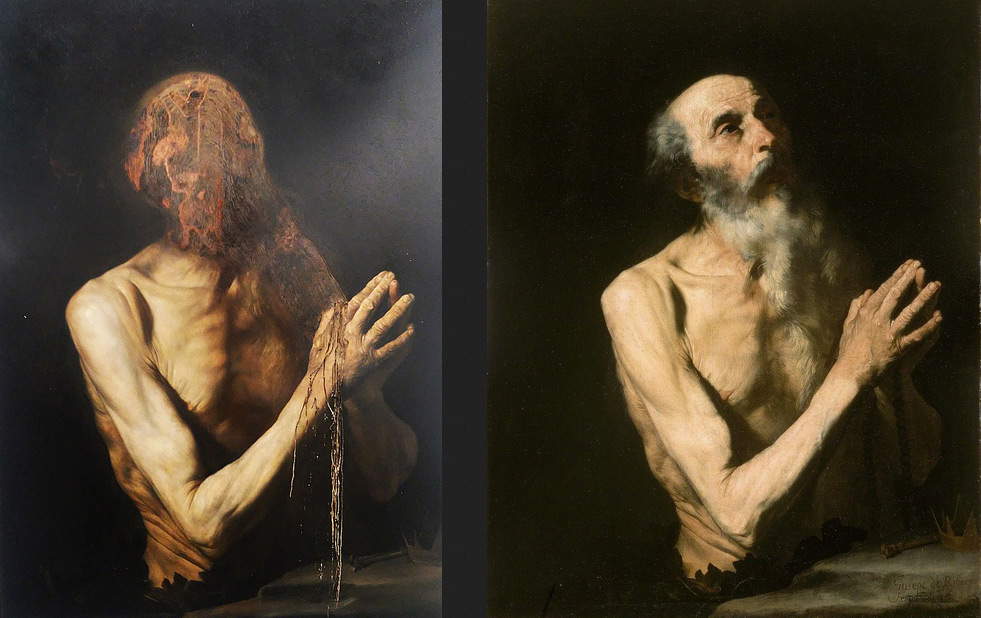

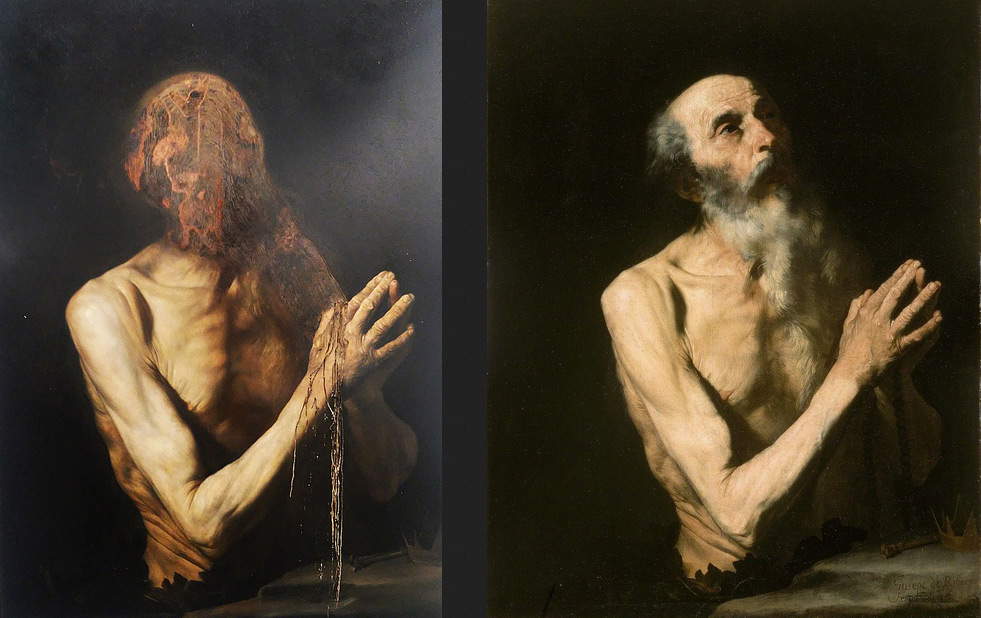

The Baroque is just one of the segments of art history that I plunder, with a continuous focus on the figure of José de Ribera, whom I have imitated dozens of times. The Baroque convulsion is actually not even congenial to me, because it involves a dispersion in space, in conflict with my hieratic sense of center. But Ribera is essential in layout and turgid in modeling, so a body of his in the night always offers a perfect presence for a long series of alterations that starting from a fifteenth-century painting would be unthinkable.

|

| Left, Nicola Samorì, The Ants (2017; oil on copper, 100 x 100 cm. Courtesy Galerie EIGEN + Art, Leipzig/Berlin). Right, José de Ribera, Saint Paul the Hermit (ca. 1632; oil on canvas, 132.7 x 106.7 cm; Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum) |

|

| Left, Nicola Samorì, The Fall of the Giants (2017; oil on copper, 70 x 50 cm). Right, circle of José de Ribera, Saint Jerome (first half of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 92.7 x 70.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Left, Nicola Samorì, Lucrezia (2010; oil on panel, 100 x 100 x 5 cm). Right, Guido Cagnacci, Lucrezia (c. 1636-1640; oil on canvas, 114x112 cm; Private collection) |

In your opinion, how much do you think contemporary art, of which you are already an established exponent, is or should be linked to the art of the past? Relative to the themes you favor, which of these do you take from ancient art?

I do not believe in the duties of art, but I have faith in its enormous memory that obliges us to a confrontation with the pre-existing. It is difficult, after all, to think of a new gesture without an encyclopedic curiosity about those who have gone before us. There is then a sense of discipline in ancient art, even in that which was most transgressive in its time, which makes the works, in my eyes, more exciting and which teaches us to complicate our lives in order to master the form while deriving solid satisfaction from it. Regarding the motifs of the past that I favor I would certainly say lyconography of the saints and the cruel calendar of their martyrdom.

The great part of His works belongs to pictorial art: on paper, on panel, on copper, on linen. Do you prefer painting more than sculpture? In the case of sculptural works, do you apply the same influences and meanings as in pictorial works?

It is easier to proliferate pictorial works than sculptural ones; this is the main reason for the imbalance. But the oscillation from one practice to the other is necessary for me because when painting starts to stink I need to detoxify with stone, and when the dust starts to haunt me I go back to painting. My hands are more at ease with sculpture; however, a huge amount of painting has generated automatisms that also condition any plastic evidence of mine.

What function do you give art?

Larte is a hole in time, something that anesthetizes its rush.

What projects do you have in your drawer for your next works or exhibitions?

I am now working on my next solo exhibition in Berlin, which will be held at Galerie EIGEN+ART in October: a monumental fresco that optically engulfs, like a chasm, a black stone sculpture. On either side are small, meticulous visions that fix man’s fear like episodes under a microscope.

|

| Nicola Samorì, Untitled (2016; fossilized wood, 45 x 20 x 17 cm. Courtesy Monitor Gallery, Rome) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Lucy, detail (2016; Carrara marble and lunar fragment, 90 x 35 x 30 cm. Courtesy Monitor Gallery, Rome) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Anulante (2018; oil on copper, 70 x 50 cm. Courtesy Monitor Gallery, Rome) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Corpus Christi (2017; oil on copper, 40 x 30 cm) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, In principio era la fine (2016; oil on copper, 30 x 20 cm. Courtesy Monitor Gallery, Rome) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Saint Peter in Hell (2016; oil on linen canvas, 300 x 170 cm. Courtesy Monitor Gallery, Rome) |

|

| Nicola Samorì, Magdalene (2010; oil on panel, 70 x 50 cm) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.