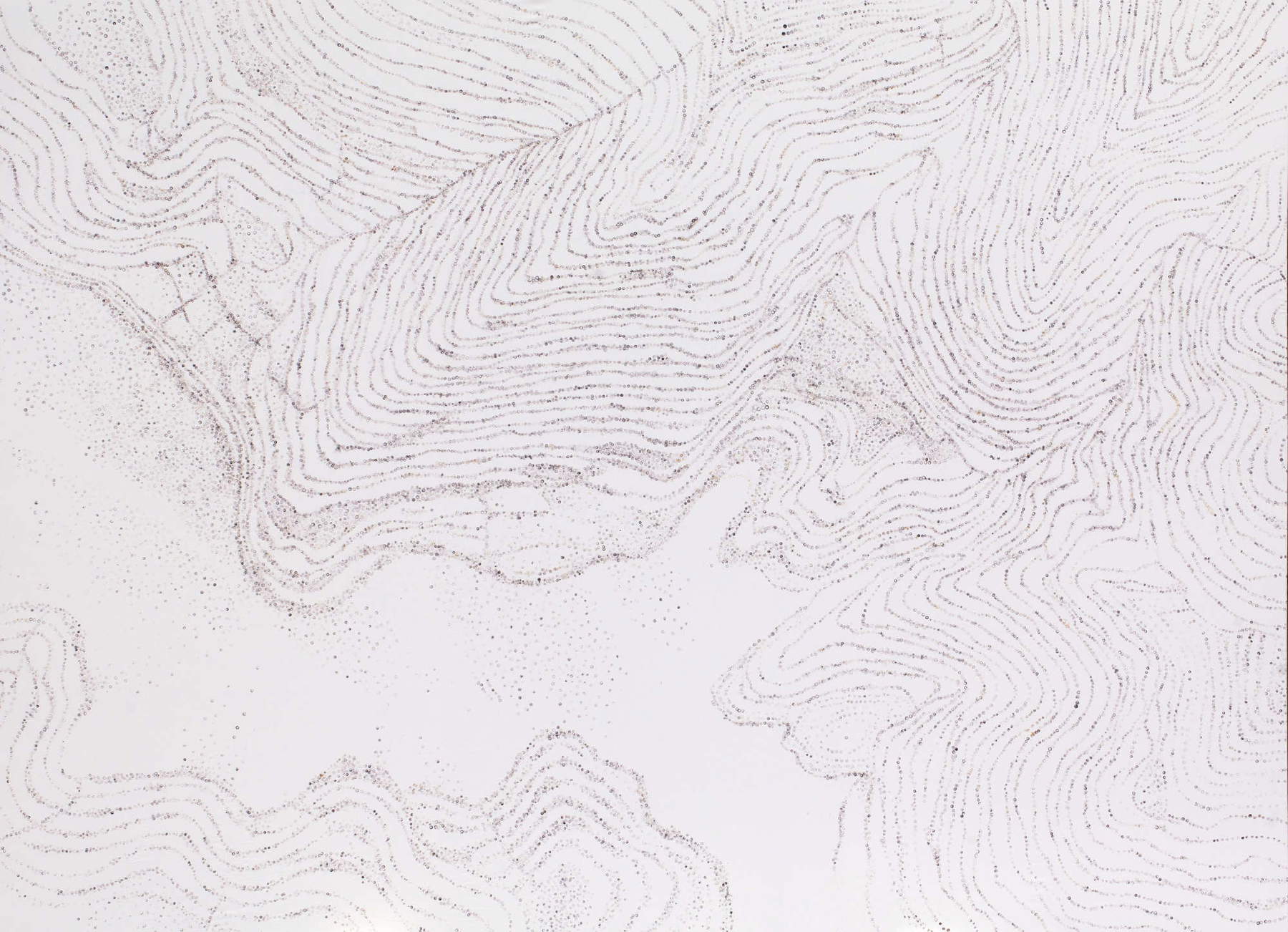

A research poised between the use of primordial materials, the techniques of tradition and a contemporary vision contaminated by technology. It is that of Catherine Sbrana (Pisa, 1977), an artist who, through geographical imagery, investigates the liminal spaces where nature and culture, human and nonhuman, meet. After classical studies, she studied painting restoration at the European Institute of Operative Arts in Perugia and graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara in Painting and Visual Arts. The collection of traces, residues, textures and the direct relationship with the landscape are the focus of his work, which makes use of different media. The sign of poppy capsules becomes a natural pixel to compose large maps while soils, juices and vegetable pigments obtained from wild and dyeing plants, harvested or cultivated, become the material to paint landscapes inspired by digital visions, objects and still lifes in ceramics record the encounter between human time and the cyclical time of nature. Since 2009 she has co-founded with Gabriele Mallegni Studio17 manifacture and multidisciplinary space dedicated to visual arts and design. In 2018-2019 she curated together with Luca Carli Ballola, Irene Balzani and Michela Mei, A più voci, a project of the Strozzi Foundation for people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers; in 2022, again for A più voci, on the occasion of the Alzheimer fest, she presented the workshop L’insurrezione dei semi, inspired by a text by Giuliano Scabia. He has exhibited in numerous exhibitions in Italy and abroad.

GL. For most artists, childhood represents the golden age when the first symptoms of some interest in art begin to appear. Was this the case for you as well?

CS. I think a certain kind of symptoms are common to many children, only in some cases they don’t stop occurring and last a lifetime. My parents were young and newly working, they bought graphics and paintings on installments in a gallery in Pisa, the Giorni gallery that dealt with different artists from Pisa and elsewhere: Tono Zancanaro, Renzo Bussotti, Uliano Martini. They hung these paintings and etchings, some very dramatic, everywhere, even in my and my brother’s room, we would look at them for a long time and to exorcise we would make up stories. Uliano Martini was a relative of ours, he painted skies, the rubble of postwar Pisa, the landscapes of the Monti Pisani where he had done the resistance of which he was an active part and important witness, we had at home one of his Joan of Arc inspired by a sequence from Dreyer’s film. I used to meet him when I went to town with my mom, he had a studio near the church of San Michele in Borgo stretto. I was little and this tall, thin gentleman with white hair and a black beret would bend down to greet me, behind his head the marbles of the church and the motherhood of Wolf of Francis. He was different, he smelled different, a resin smell that I would get to know years later, he seemed to come from somewhere else. I looked at it, and my thought was that whatever mysterious place it came from I definitely wanted to go there too. Uliano was like an epiphany and for me he was perhaps a bit, without knowing it, like the pied piper of Hamelin in a gentle declension and not at all creepy, he died a few years later, I would have liked to have been able to hang out with him as a teenager and as an adult. I was sociable but lonely, I could be with others but I was really happy when I was with animals, cats, plants and books and had something to draw or manipulate and that hasn’t changed at all. I would build cities and houses with dirt and then erase them by flooding them with a bucket of water, with a friend of mine I would do archaeological excavations in the vegetable garden. I used to play a lot with my grandmother Nara, a young grandmother, she was in her forties when I was born, like many of her generation her childhood had been interrupted by the war and because of that, I realized many years later, she played as a child among children tirelessly and totally. We made dish and tea sets out of aluminum foil, sewed dolls out of socks, and embroidered our hands under our skin with needle and red and blue cotton thread to draw new little veins. My grandmother is still with me, she is 95 years old now. I would fall asleep at night listing the colors of the sky and clouds to try to reproduce them the next day with crayons.

You also had, as happens to many, a first artistic love, which one?

It was a sudden and violent love that left me speechless. It was for Evening Shadow at the Guarnacci Museum in Volterra when it was still in the old domed case that looked like a space capsule, and for Ilaria del Carretto also seen, for the first time, as a child. A shadow and a dead body. In front of me were the immaterial and the unrepresentable. Two works that do not fit into space but, rather, create a space around them and speak of that which cannot be said, which cannot be explained, which cannot be stopped. The daughter of the potter of Corinth traces on the wall the profile of the beloved who must leave: representation, in our culture, comes from absence, from loss.And then Ilaria had a dog, and I could never conceive of existence without the closeness of another animal.

What studies did you do?

Classical High School, then I studied painting restoration in Perugia earning a diploma as a technical attaché and graduated in Painting and Visual Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara. I would do this nonlinear path again because it allowed me to follow my inclinations and never feel perfectly adherent, comfortable, in each of these environments, which I think is important. From high school I learned the vitality of things that are said to be dead, I learned to try to look for the root of things and words and to cultivate everything that is considered useless in this society. Liceo Classico is also a fairly elitist school, in the sense that most of the pupils come from affluent social classes and from families that make a certain kind of profession: the encounter with this reality, which was unexpected for me as a teenager, and the observation of certain dynamics determined my attitude and reinforced my rejection of criteria for evaluating others linked to social and economic belonging. At the Academy, on the other hand, I began to realize that perhaps I could do what I do.

Were there any important encounters during your training?

The encounter with Homer, Sophocles, Euripides, Ovid and with Ballard, with Shelley, Byron and Toma’s poems. All the people I mention in this interview were important for different reasons. Simone Mancini, who is now a restorer at the National Gallery in Dublin, was my teacher in the restoration course in Perugia, I think he doesn’t know how much his sensitivity combined with his practical sense made me see the life of paintings and works differently. At the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara I was attending the Painting and Visual Arts course taught by Omar Galliani we used to compare and talk a lot, he introduced us to some of his artist friends such as Marcello Jori and Vettor Pisani whom I still remember as he wandered around the classroom. One day, it was 1998, I showed up dragging a sack full of the soil from my grandfather’s garden that I had brought by train on the stairs of the Academy and with that I repainted Millais’ Ophelia in mud on a large rough canvas, a relationship of trust and esteem was established. In those years there was less rigidity in the rules, more freedom, the classrooms of the main subjects were always open during the week, those who attended more assiduously won a whole wall, a stool and a small table, a studio in nuce, in the middle of the classroom was a large table full of books and magazines, for the first year I did not leave the painting classroom, I stayed behind with all the supplementary subjects. All my friends from those years at the Student House were important for my education, in Carrara I also met Gabriele Mallegni, my partner, a fundamental personal, we have grown and are growing together, sometimes we even work together on common art projects like Lapidaria and Una brillante Memoria, a project on the imprints of the injuries left by the war on buildings, and we have a molding workshop and a manufactory where we produce design objects and objects of use. Attending Torano, above Carrara, and the Quarrymen’s Circle, then run by Vladimiro known as “Togliatti,” also put me in touch with a completely different reality from the one I knew, in some ways even harsh and strong. Very important were the encounters with people far from the art world, I am not very comfortable in cenacles and for me to hang out with people who do different things is natural, vital and very fertile. During the summer breaks during the Academy I worked on an organic farm near my home, and the people I met taught me valuable things: the rudiments of keeping a vegetable garden, planting how to recognize certain plants. Immediately after the Academy I started working in an antique and handcrafted frame restoration business where I worked for almost nine years, the owner Elena Baroni taught me a craft that is with me even now, gilding, faux wood, faux marble, she taught me organization in work and not to waste materials, it took me almost two years to learn how to decently patina a gilding. And then Andrea Barsi, professor of foundry, who introduced me to Gabriele and taught us so much about casts and molding.

Over time how has your work developed?

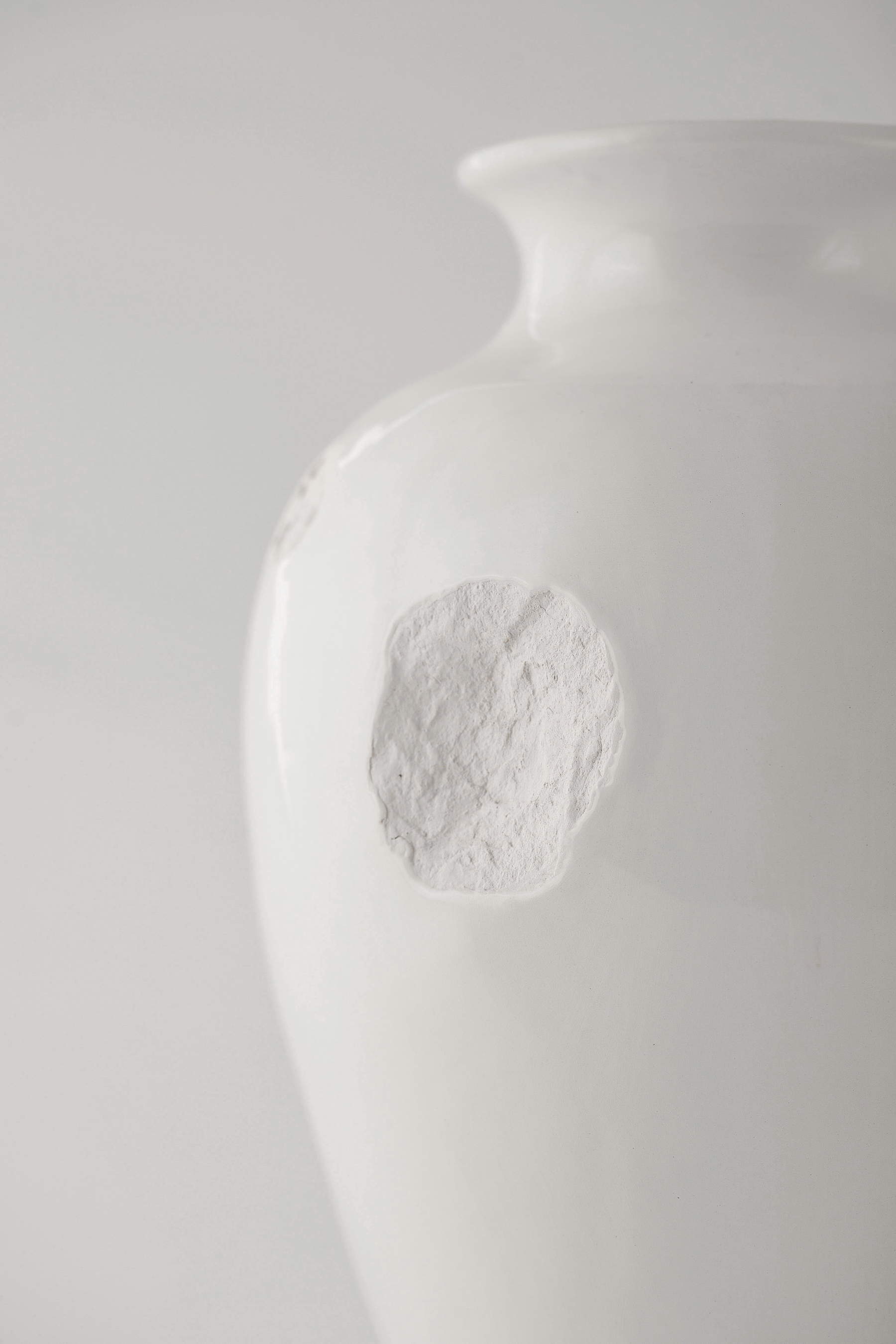

To say it from the inside is difficult, although the topics of interest basically have been more or less the same for years, it has certainly transformed. I like to search and in this search get lost sometimes with joy and sometimes with great frustration, I hope to have time so that my work can be transformed again. The interest in landscape, the relationship with nature and the nonhuman and all the symbolic, dramatic and magical aspects related to it have always interested me. I started from painting and drawing, in my early years at the Academy between 1997 and the early 2000s I almost exclusively used ephemeral materials collected from nature such as mud, ash, with which I traced botanical plates, plans and quotation works or which I dusted in floor installations (Sakros, Carrara, 2008). At some point I felt limited in that exclusive choice, I did not want it to become a method, a custom, a formula for all occasions that in those years was becoming an increasingly common practice. For me it was a choice anyway linked to the idea to the themes I wanted to investigate and still today these materials are part of my research and I use them when I need them. About ten years ago I discovered ceramics and started to not only use raw and ephemeral materials, I felt stuck and ceramics gave me back a fundamental dimension, that of pleasure and play and, in a way, freedom. What unexpected happens on our path is a form of discovery that we cannot give up in order to remain faithful to the idea we have made of ourselves or “to remain faithful to those who look at us,” to quote one of my favorite songs.

Has your work always been based on assemblage or is this a mode of operation you have recently adopted?

The latest works stem from my encounter with ceramics, which I have been using and working with since 2014. I exhibited the first prototypes of this cycle at Studio Gennai in 2018 and in Paris at 59 Rivoli. I would say they are false assemblages, apparent assemblages. They look like combinations of different materials or objects but they are made of one and only one material, ceramic, which in these works represents itself but also the other from itself, imitates other materials and textures. I think of Autosomiglianza in which some everyday objects are recaptured by natural forms and textures, lose their original semblance and function and become the theater of the never-peaceful relationship between man and nature. They are perturbing objects that come from a lost world and already belong to another world, to a new, very ancient aesthetic that combines natural formlessness and the trace of human work. Layered within these works were Palissy’s sixteenth-century ceramic visions, admired in Paris shortly before the lockdown, Ballard’s stories and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, I do not know in what order. The mimetic capacity of ceramics interests me very much, there is a part of research on the technique of the material, the study of patinas and surfaces that often leads me to new visions and works. Because of this, but not only this, I have always been linked to the manual, “artisanal,” laboratory work that I make myself and that is an endless source of stimuli, fortuitous cases and disasters, of discoveries and transformations. For me it is an irreplaceable way of thinking and designing. My work has always also been linked to immersion in the landscape and the act of collecting materials, traces, textures as parts of a large archive under construction, these works are also born from this practice.

When you start a work, do you already have a clear idea of how it will develop, or is there room for changes along the way?

It depends, but I usually start with a clear idea that I then change punctually during the realization phase following what happens. For more technically complex works I always start with a clear idea of the technical steps to be taken, but there are always surprises and so I often have to change my method and approach.

Gabriele Landi: Do these objects you make also have to do with your personal memory?

The nature of the sediment that precipitates within an idea, fortunately remains largely mysterious, some of it emerges and is recognized. I am the daughter of a craftsman, a carpenter and furniture restorer, I remember his workshop as a place capable of suspending time, markets and the homes of collectors and clients filled with objects of art or use that carried a history and mystery, immobile presences that in the imagination were set in motion, familiar objects that revealed a perturbing aspect. Some of the works/objects in this cycle actually resemble small domestic ruins, hybrid and alienating still lifes in which the relationship between the human artifact and the work of nature, which, removed, re-emerges and re-conquers, is highlighted. I remember an art history teacher in junior high school telling how Morandi used to bury his used brushes in the garden; he did not like the term still life and preferred the German still leben, silent nature. I think about how important and germinating is this silent and remote dialogue with things, with nature, with the nonhuman, as in Lapidaria, an archive of stones works and objects, started in 2019 with Gabriele Mallegni. I would say that almost all my works, open cycles that return, start from daily experience and are linked to memory, like the drawing work with poppy capsules that draws on a childhood memory and together with the very ancient symbolism of this wild plant well rooted in our imagination. Since childhood I have lived in the countryside, near a mountain, and in nature and in the fields one always finds treasures that contribute to the formation of a personal mythology. Observing nature is the most powerful tool I know to accept the unceasing transformation of things, and our own as well. I, too, will somehow become part of the landscape I observe again, in another form.

I would like to ask you to tell your idea of nature?

Nature in the end does not exist, it is an idea, as your question says, a projection, a phantom, a cosmological vision capable of founding the landscape, the world and determining the way we move, in which we shape and are shaped. Nature is a complex system of relationships that embraces the transformations, the movements of the living (and nonliving) and of which we forget that we are part. The Greek physis (nature) defines everything that grows, is born and dies and contains both the concepts of being born and generating. An original unity that includes the living all, including man, and which early philosophers investigated without making distinctions, then Aristotelian categories began to draw the hierarchy of the living and the non-living, a divide that in our European and Western culture has become deeper and deeper and has served to perpetrate injustice, to enact the exploitation of bodies, animals, and nature. There are cultures that have developed and maintain a much more articulated, broad concept of nature, made of relationship and mystery, I was struck to discover that some native cultures in Hawaii for example believe in self-determination, in the life and will of stones and rocks. The human animal, in our culture, in addition to speech and logos has developed a special ability, which is to build enclosures and draw up classifications. In these fences we put everything we want to remove or protect, which then is often the same thing because by protecting something to which we do not recognize life and dignity we actually remove it from our experience, our life and our imagination. The garden and the vegetable garden are born as fences to distinguish what good, especially in a utilitarian sense, has a right to citizenship. Here, in my work I often find myself investigating what happens in those enclosures, in the concluded horti of the imaginary, in the interstices, in the gaps, in those liminal places where it is possible to encounter persistence and presence, the other in all its forms. My idea of nature resembles a place that seems distant from nature, a concrete island, a traffic island. The island in traffic is a hortus conclusus in reverse, a place circumscribed and then abandoned where laws and choices are established not by humans but by the presences and survivals that inhabit it, by animals and ancient, pioneering, allochthonous plants seeking passage. This life a in some cases minimal and almost invisible, in others teeming and explosive returns these spaces from the dimension of nonplaces to which man had destined them to that of real living and experimental places. Together with Gabriele I visited many of them, traffic circles where hemp and datura grew, other small primeval forests in the midst of traffic, now inaccessible, a research that should end with the publication of a small herbarium of concrete islands. And passing through these places it occurred to me that indeed guard rail has the same root, from the Gothic gart (fence) of garden. Just these days I was reflecting on Francesco del Cossa’s panel painting where Saint Lucy, an iconographic unicum, holds a plant looking at us with wide eyes. St. Lucy is after all one of the personifications of nature; in popular tradition her eyes are from time to time likened to hazelnuts or shells; it is an other, non-human gaze. It is no coincidence that some Demeter cults later turned into the cult of St. Lucy in some southern countries, and Demeter as St. Lucy is linked to the alternation of the seasons, of light and dark. But what interests me is that this vegetal gaze, this image that seems to have been painted yesterday is for man perturbing and difficult to sustain just as for Derrida it is the gaze of his cat observing him naked in the bathroom, from this discomfort and this inability to reciprocate the gaze of nature arises the philosopher’s whole reflection on the question of man animal and man nature and the problems, the doubts that this (failed) exchange can generate..

And as if your work is a distillation of the mysterious mechanics of cosmic cycles. What role do time and space play in all this?

A fundamental role, as in all human affairs. Time and space are multifaceted concepts, moving and interacting with each other. We are constantly moving through space trying to mark our paths and measure time, to fix it or to meet it, to curb it or to scan it. I think of ancient maps that trace vital paths, representations of the earth often drawn on the earth itself. Primordial drawings, made of lines and dots, traced by experience. A physical and symbolic place of representation where these concepts meet: the time of traversed space. Some of my works seem to me to be different attempts to measure time: the cyclical time of nature that resonates with my explorations and my time of collecting capsules, or objects and textures, the time of the hypnotic and repeated gesture of imprinting the mark on the canvas. The landscapes inspired by digital programs such as Google Earth are a reflection on space and time: we move out of time and explore landscapes that do not exist, yet our aesthetics and perception are also based on this. However, these landscapes are painted using soils, juices, pigments that I collect or grow in the real landscape, with sometimes very long timescales, thus combining two visions and two experiences of the landscape. And then the working of ceramics with its times and laws after years always to be understood, conditioned by humidity, temperatures, which asks to be known and observed and prevents a superficiality, an imposed speed. Perhaps all this is also an attempt to reappropriate space and time according to other laws, perhaps the cosmic ones you mentioned and at the same time very earthly and human. When I go to Rome, for some years now, I play a game it is called Ways of Measuring Time I photograph details of stones, of grits, balls lost in the Tiber in perpetual motion in the eddies of the river and I take photos and videos of them that I collect in an archive. The non-human time of geological eras, of currents, flowing and sometimes meeting with human time and history. This particular glimpse heals us from the eternal, very fast present to which we have consigned ourselves. It returns us to a larger reality, to larger clocks that measure slow movements, transformations and stratifications and has the ability to condense different conceptions and aspects of time. If I look at Mr. and Mrs. Arnolfini I see time, the morning light filtering through the window, but if I get closer I see time in the craquelure of the pictorial layer, in the micro-cracks of the table, in the movement of matter. Here art gives us this great possibility to get so close to things, to then look at them from afar, to make present what is not, to step outside of time, to experience other times and spaces.

What importance do you attach to the materials you use?

A great importance, the choice of material is closely linked to the concepts and ideas, the themes to be investigated. In the landscape work related to the views inspired by digital programs I went in search of soils, minerals, I processed and burned branches as for vine black, and I cultivated some dyeing plants including ford the Isatis tinctoria from seeds given to me by Alberto Lelli, an agronomist from Rieti who dedicated his life to this plant. Alberto grew a Roman-era ecotype of the Rieti ford, at the beginning of my experiments he gave me the seeds, followed me with my small planting and explained the extraction recipe over the phone. I carry the plants forward each year so as not to lose his precious gift. Alberto died a few months ago, and sometimes I think of how many ford plants will continue to grow from his seeds in the Rieti countryside and in my and other gardens, a form of continuity and memory stronger than so many other things we can leave behind. In the drawings with poppy capsules, on the other hand, it is the capsules themselves that become the protagonist material as matrices to be imbibed or in the summer drawings already endowed with their own natural pigment. While ceramics in its raw form of clay is a very sensitive material, it registers every mark, every force, every fingerprint, it gives us back the world and simultaneously its own disappearance. I think about how ceramic is linked to the everyday and at the same time to a transcendent and symbolic dimension, it is the first material with which we built storage containers and by doing this we circumscribed the void by separating it from the rest and materializing it where it was not. Here at the studio, as I work, I wait for a definite sound of the void becoming saturated, of little bubbles moving the slip and being absorbed: it’s a sign that the pieces have come together and that things of different guises have begun to dry, to shrink as one. I happen to use nontraditional materials, as I did recently with the gold patinas used for scratch-offs that I used to cover lost landscapes by likening them to the pure gold of medieval plates.

Everything you tell seems to allude to a spiritual praxis of the work. Does this dimension exist in your work?

I believe that the spiritual dimension belongs to everyone, that it is inextricably linked to every creative act (in a broad sense) and that it can emerge even and especially unintentionally. I have always experienced this dimension freely, I have always felt the power of images and the sacred in nature and things. Art brings us closer to the mystery of things without revealing it or naming it. It gives us a chance to create worlds and visions, to investigate the secret relationships between things and the connections we have lost. Through matter we get in touch with the life cycle, with transformation, and in this sense working with collected materials and ceramics can also be a spiritual exercise. I am reminded of Carbon, one of my favorite Levi stories: the almost epic journey of an atom through the chemistry of things and through time, a material tale at the same time deeply spiritual. This little carbon atom that mutates until it gets into the body of the writer,and thus participates in the writing of the story, in the creative act, elicits wonder, and wonder is always at the beginning.

What happens to works when there is no one to observe them, can the existence of a work of art be without the presence of an observer?

The work lives in relationship, often thanks to those who observe it or those who come into contact with it are enriched with readings and meaning. But it does not cease to live if it is not observed. I think of a forgotten work, shrouded in solitude and silence that perhaps ceases to live as a work and survives as something else, as a fragment, changes over time, is inhabited by other presences, by microorganisms. Its existence does not cease but abandons its identity and its first meaning until it finds a new observer or new destinations, uses and meanings. What happened to the Evening Shadow while it was underground? Or to the Laocoon? Does their disappearance and discovery contribute to their settling more firmly in our imagination? Have they had a secret life that has resulted in their changes of form, patina mutations, and misses that, as in the case of the Laocoon, have led to different and unexpected interpretations and readings. Somehow the works wait, sometimes dying and being reborn, sometimes being transformed.

Where do you think the artist stands in relation to his work?

Inside and at the same time I hope far enough away to be free to keep looking.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.