Until May 7, 2023, the Crucifixion by Masaccio (San Giovanni Valdarno, 1401 - Rome, 1428) from the Capodimonte Museum in Naples is on its way to Milan, to the Museo Diocesano "Carlo Maria Martini ." A real exhibition itinerary has been designed around the masterpiece, curated by Nadia Righi, director of the Diocesan Museum in Milan, and Alessandra Rullo, curator of the Department of Paintings and Sculptures of the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries of the Capodimonte Museum and Real Bosco, entitled Masaccio. The Crucifixion. From the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. A Tribute to Alberto Crespi. We asked director and curator Nadia Righi to tell us about this project in its various aspects, and here is what she told us. The interview is by Ilaria Baratta.

IB: Masaccio’sCrucifixion, now the protagonist of the exhibition at the Museo Diocesano in Milan, certainly invites, given the period, a reflection on Easter, but what is the intent of the exhibition? Did it arise from a collaboration with the Capodimonte Museum?

NR: Yes, actually the reasons are more than one. First of all, like every year during Lent and Easter, the museum organizes an initiative to help visitors enter into reflection on the Passion of Christ through art. Normally at Easter we don’t do exhibitions with a single work (this is a format that the museum usually uses at Christmas time for the exhibition-dossier Masterpiece for Milan): it was a favorable combination of things, born also from the fact that for a few years we had been thinking of organizing something celebratory on the occasion of the centenary of Alberto Crespi, the Milanese jurist and collector who donated to the museum, even before it opened, a wonderful collection of gold fonds and who would have turned 100 on May 1, 2023. So already a couple of years ago we were thinking about what to do to pay tribute to him and to enhance the collection, and within a collaboration that had already begun with the Capodimonte Museum on previous occasions, the idea was born to bring to Milan the gold fund par excellence, also to emphasize a technique and at the same time to make our visitors rediscover the Fondi Oro collection, as in fact is happening.

Why was this particular work chosen?

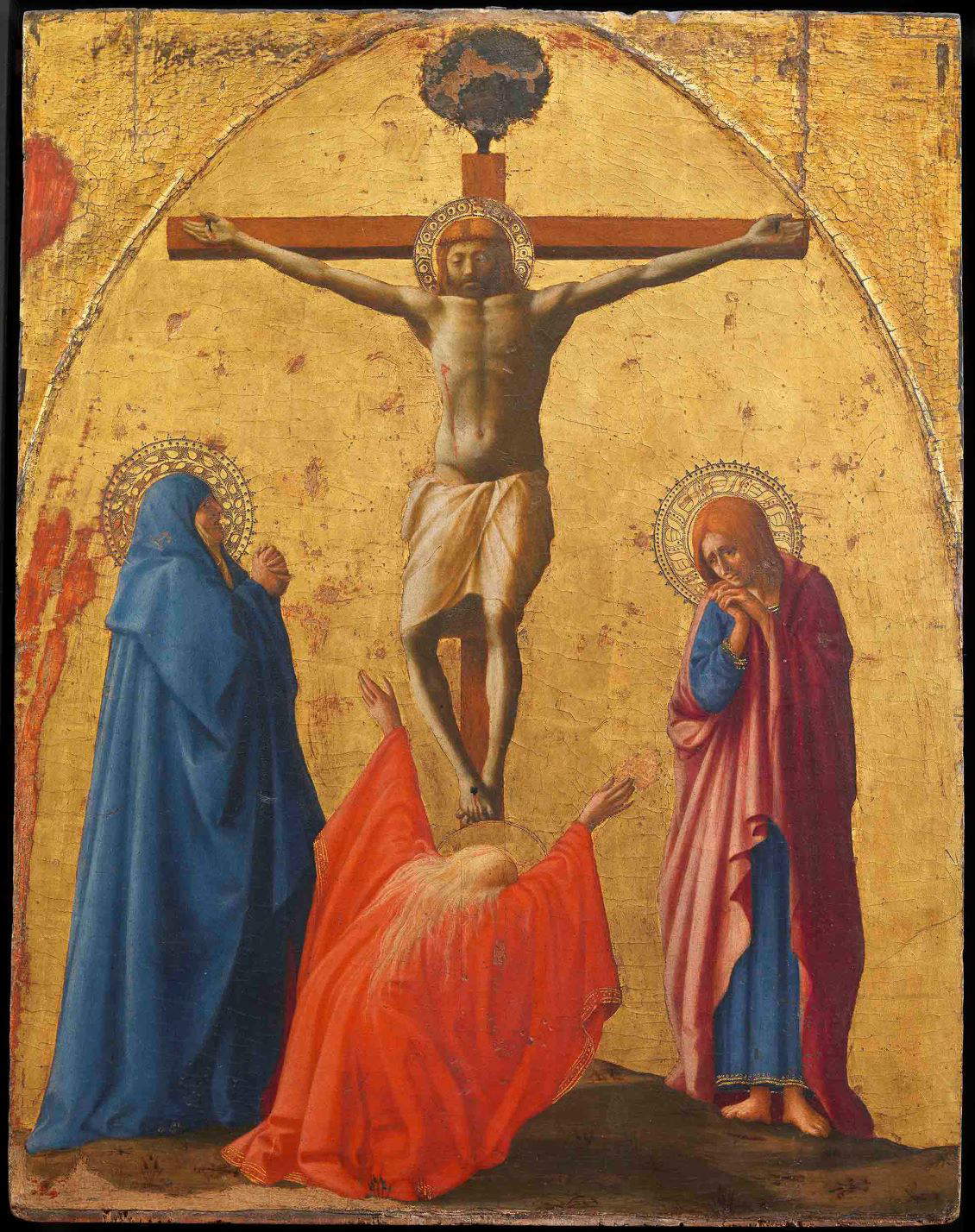

It is an extraordinary work that marks the change of language in early 15th-century Florence. Masaccio, who had already painted the Brancacci Chapel and who was about to begin work on Santa Maria Novella, is paradoxically obliged (he who had broken through the wall in Santa Maria Novella and created scenes of absolute reality in the Brancacci Chapel) to use the gold background, which was anti-realism and was now part of a world that certainly in his stylistic conception no longer existed. He is thus obliged to do something against all his inclinations, yet the client, the notary ser Giuliano di Colino degli Scarsi obliges him and he accepts the challenge, going so far as to break through even the gold ground. This is the first time he dares to break through the barrier of the gold background, and Masaccio succeeds here in creating a scene of absolute realism and naturalism, as he knew how to do, combining and taking up the teachings of Brunelleschi, of Donatello, and translating them into painting, even on a gold background. With this absolutely extraordinary perspective-spatial and volumetric vision that in itself in the gold background we would never expect.

So we could say that Masaccio was a revolutionary in this respect?

Absolutely. Even Vasari himself marks the Giotto, Masaccio, Michelangelo line in the direction of a progressive awareness of space, form, and dialogue with classicism.

And in the composition of the work, what is the revolutionary character of this precious panel?

Masaccio uses foreshortening in an absolutely daring way: those who look at the work hanging on the walls of a museum, as in our case, at the visitor’s eye level, think that Masaccio has got it all wrong, because Christ has too short legs, he is without a neck, but in fact Masaccio thinks of the work knowing already where it would be placed. The panel was in fact the cymatium of the great polyptych for the chapel of the notary ser Giuliano, inside the Church of the Carmine in Pisa, and we know from documents that the polyptych measured eight fathoms and three quarters, so it was five meters high including the altar. A truly considerable height, and Masaccio made this work already imagining the point of view of the faithful, the observer. The foreshortening actually, the moment we relocate the work at that height, as at the museum we did virtually, absolutely takes on meaning and we realize that the perspective and the point of view are perfect. He then later adds the figure of Magdalene (one glimpses underneath the carvings of the drawing of the cross that was to reach up to the hill of Golgotha); he adds it later precisely to give more strength to the composition. The viewer’s eye is drawn to this extraordinary figure, painted in that bright red that looks almost like a flame, an arrow, and her position is also extremely innovative: Normally Magdalene is hugging the cross, wiping with her own hair the blood flowing from the wounds of Christ’s feet, and instead here she is not touching the cross, she is on her back with her head bent forward, her hair tousled, in disarray, and te hands raised as if in a shout, a prayer, an invocation. Compositionally, too, this figure constitutes an absolute novelty, not least because the feeling is that the hands go beyond the cross, precisely that Masaccio breaks through the gold background, as mentioned earlier. It seems that the gold is sent back no longer as a spatial limit but almost as a perspective, as if to recover its symbolic meaning. Gold is a sign of the divine, the eternal, the Resurrection, we could say.

We said that the exhibition is meant to be a tribute to the memory of Alberto Crespi, that is, the one who donated his collection of gold backgrounds (over 40 plates) to the museum. When did the donation date back and what are the most significant works?

The donation entered the museum in 1998. It had been presented in an exhibition at the Fondazione Stelline in Milan, and when the museum opened in 2001 it was already part of the Diocesan Museum’s collections. They are works that Crespi had collected during his lifetime, helped by extraordinary scholars, first and foremost I like to remember Miklós Boskovits, who had advised him in the passages, acquisitions, and attributions; they are works from various fields, ranging from the fourteenth to the early sixteenth century, mainly from the Tuscan, central Italian, but also from the Veneto region, there is a single Lombard work by a fifteenth-century anomimo (actually four compartments that were part of the same polyptych) and then there are works by Nardo di Cione, Agnolo Gaddi, Sano di Pietro, Gherardo Starnina, Nanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, and Paolo Veneziano.

The

TheBesides the gold background, is there a link or elements in common between Masaccio’s Crucifixion and Crespi’s gold backgrounds?

The link is given by the continuation, because in the Gold Grounds Collection the visitor has the opportunity to see how painting was done on a gold ground in Italian art. So one further perceives the break that Masaccio marks, because in the Collection there are works executed at the same time, at the beginning of the 15th century, indeed even later, and one realizes, all the more from the very comparison, how revolutionary and extraordinarily innovative Masaccio was.

How has the museum planned to bring the public closer to this theme of the gold backgrounds and thus to the exhibition?

Visitors are invited to follow a didactic and didactic path in which Masaccio’s art, his revolutionary scope, the whole history of the polyptych, the collecting history, the history of the Chapel, the dispersion of the polyptych whose pieces are now in various international museums are explained on panels and also through illustrations; the criterion of the arrangement is also explained, the reason for the acquisition of the new Renaissance frame that from now on will accompany the painting also to the Capodimonte Museum when it returns to its location is given, and moreover, in a darkened room, a video is projected that digitally reconstructs the entire polyptych in life size, precisely to restore the feeling of the positioning of the panel and thus the rightness of Masaccio’s perspective reflection. And only at the end, after all this path, do we arrive in front of the work, where the visitor is left alone with the opportunity to enter into a relationship with the work and to look at it, enjoy it, and deepen all their reflections. The exhibition continues physically with special signage in the Fondi Oro section, which we also did not want to touch out of respect for the very collector who had wanted it that way (the Fondi Oro Collection is a wing of the Museum that was conceived by Crespi and architect Giovanni Quadrio Curzio at the time: a sort of white cube with a different layout from that of the permanent collection). Within the Gold Grounds section we then put a series of graphic references to the Masaccio exhibition, which has as its subtitle precisely “Homage to Alberto Crespi,” and we took the opportunity to explain with a series of didactic panels the various techniques that are used on gold backgrounds, which is one of the curiosities that visitors always have when they visit that section, so it seemed like the right opportunity to delve into this aspect as well, which always arouses curiosity and interest in the public. There is also a series of guided tours offered, which are taken care of by our Educational Services. In the museum we also have in this period a collaboration with students from the Salesian Institute Sant’Ambrogio in Milan who welcome visitors and accompany them to see the gold funds when the public finishes seeing the exhibition dedicated to Masaccio. And we also have a collaboration with the Galdus goldsmith school in Milan, whose students do gilding demonstrations; instead, for both adults and children we offer workshops on the technique of the gold ground. So often guided tours or narrated tours are complemented by workshops or demonstrations that help precisely to understand this technique. Normally, both we and our Educational Services think about the tours precisely by trying to intercept what we feel are the needs of the visitors, and having realized in recent years that the topic of technique is also one that people are not familiar with, so they ask for information, we decided for this time to focus on that aspect as well.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.