Luca Pancrazzi: "Painting? It's a window. And it is the main ring of art."

A conversation to learn more about the art of Luca Pancrazzi (Figline Valdarno, 1961). After his academic studies in Florence, Pancrazzi traveled to the United States where he met Jo Watanabe and worked in his studio making graphics and wall-drawings for Sol Lewitt. Until 1992 he worked in Rome for Alighiero Boetti. Since the 1980s he has been the author of research based on the analysis of the artistic medium, its ramifications, the creative possibilities of error and the composite use of techniques and materials. Metropolitan space and landscape, in their continuity with the anthropic gaze that defines them, are the themes treated with more assiduous continuity. He expresses himself through painting, drawing, photography, video, environmental installation, sculpture, shared actions with other artists and editorial projects. He has been exhibiting since the mid-1980s and since 1996 has been invited to participate in a series of international exhibitions including the Venice Biennale (1997), Vilnius Triennial (2000), Whitney Museum of American Art at Champion (1998), Valencia Biennial (2001), Moscow Biennial (2007), Quadriennale di Roma (2008). Some among the many public spaces that have presented his work: P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center (1999), Galleria Civica di Modena (1999), Museo Marino Marini (2000), Palazzo delle Papesse (2001), Museo Revoltella (2001), Galerie Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau (2001), GAMEC (2001), Museo Cantonale d’Arte di Lugano (2002), Centro per l’Contemporary Art Luigi Pecci (2002), Zentrum Fur Kunst und Medientechnologie (2003), PAC (2004), MAN (2004), MART Trento and Rovereto (2005), MAMbo (2006), Macro (2007), Vietnam National Museum of Fine Arts (2007), Pomodoro Foundation (2010), Children’s Museum of Siena (2010), Palazzo Te (2016), Santa Maria della Scala (2023), Uffizi Galleries (2024). He lives and works in Milan.

GL. Luca, for many artists childhood coincides with the first manifestation of symptoms of belonging to the art world, was that the case for you as well?

LP. All artists, and even non-artists that I know and have known, have had a childhood. As I got to know more about them and also about myself, I learned that everyone had a more or less beautiful one. So many creative, artistic childhoods, as childhoods should be, free from patterns that will fill their minds later. The condition of the artist is that of awareness and determination to be one; childhood, on the other hand, is the condition of freedom par excellence, without consciousness and awareness. This awareness can only belong to a later period, a period of learning and formation where the construction of the human being is at that stage of putting the world into criticism and at the same time falling in love with the world. Creating and destroying is part of adolescence and at this stage anxieties can turn into conditions of awareness and determination. The sexual and as we say today gendered sphere in this period of life experiences a continuous storm of conscious and unconscious stimulation and in this fluid, magmatic movement of consciousness, the structures of being that will later come to be built are formed. I remember the moment when I abandoned my early aspirations to be a documentary filmmaker without ever having tried to be one. I was already photographing as a child, first replicating the poses and photos my father took, then documenting family outings, and later, painting and drawing over the photographs I had taken. But still the consciousness of “belonging to the world of art” as you say, could not be present. The artist in my thoughts was a solitary person and a maverick who managed to prolong the freedom of childhood into puberty and adolescence and then I hoped for the adult world. If I ever began to have any flashes of consciousness of belonging to the art world probably coincided with the end of all these pure aspirations, so it must have been a time of realistic disappointment. This happened as I went along, not suddenly, colliding with reality year after year, removing myself from childhood and seeking my autonomy. The difficulties of this new social condition ushered in the realization that I was on the margins of society, and so I needed to find strength in this to be able to carry on. Even today I still feel on the margins of society and the art system at the same time, I’m not sure that I ever came to belong to either one or the other, in the sense in which you idealize it in the question you asked.

In this journey that you tell, were there any important encounters of good or bad teachers?

As soon as I was able to choose for myself, I enrolled in art high school, I was in Florence and it was the late 1970s. In that high school on the edge of the city of Florence I met teachers who were prepared and of a certain depth. My painting teacher was for those years an important first reference for painting, with him I learned to recognize contemporary art and the places where it was visible, we would go to see exhibitions and he would take us to his studio, in hindsight I could say he was a master as well as a good teacher. In the years of the Florentine academy, apart from a few outstanding teachers, the painting course was plagued by a figure incapable of giving teachings and references to his students. A baroque postmodernism weighed down by parodies of quotationism raged over everything from design to art, literature, and graphics. By choice I stopped the academy because of those carious teachings and my irrepressible need to understand. Out of the academy, in those years and the following years, until the early 1990s, fortunately, I had the opportunity to meet and work for two artists who would mark the new part of my life. I worked for them in New York and Rome, interweaving periods for one or projects for the other, and I left Florence. Two very different, opposite masters, so different that they basically met to resemble each other.

How did these two meetings come about? Did you propitiate them in some way or, assuming there is such a thing, did everything happen by chance?

In the words of A. & B. I could answer you that “things arise out of necessity and chance.”

Some time ago you told me about another important meeting, the one with Maria Luisa Frisa. When and how did you meet and what importance did Maria Luisa have in introducing you to the art system?

I met Maria Luisa Frisa in the early 1980s, in Florence. In that decade, Florence was a very active and lively city, enlivened by interesting presences and art galleries like you have never seen so many in that city. Music, design, fashion, art and experimental theater were protagonists of the piazzas, theaters of the centers, the cellars, the nights, the palaces of the discos and the salons. Private, clandestine and institutional events mingled with parties, raves, concerts, exhibitions, performances, receptions, presentations, and Maria Luisa Frisa was at the center of that artistic and cultural life, had started a periodical, and curated projects and exhibitions that were instrumental in my formation. We hung out a lot during that period and beyond, then we lost touch. In 1989 I had my studio in the Florentine countryside, in an old villa that had been saved from abandonment and the brambles that had clung to it, we organized an art residency inviting fellow artists who came mainly from Milan and Florence. It was a form of prototype for me that I then continued to cultivate over the years with different collaborative projects. Castello in Bisticci was an experience of sharing time and space, where works were made during this participatory practice. The exhibition was a side event, concluding the convivial part. Being together without a curatorial project was the purpose, getting involved without protections and without filters was the practice. During the final party, I remember that Maria Luisa Frisa was with us to share this moment, and together we came up with the possibility of documenting what had taken place through the eye of a photographer who was with us at the time and from his pen that left a testimony on an improvised booklet that was later printed.

You also owe your first exhibition at Vivita Gallery to her: is that right?

Two friends with whom I would later share a piece of the road had been invited to a contest within social events at the Manila nightclub in Campi Bisenzio. “First Graffiti Competition” was called the evening, and I participated by slipping into the graffiti artist’s shoes, the result being that I had a lot of fun and our rather performative and radical graffiti was rewarded with the creation of another graffiti inside the Vivita gallery. In the jury of the award was also Maria Luisa Frisa who therefore indirectly participated in the awareness of keeping together our group that would operate in the following years under the name Importè d’Italie. With Pedro Riz’ A Porta and Andrea Marescalchi we then continued to operate in mixed contexts devoting a decade of artistic and performative activity under this collective name.

In Florence and more generally in Tuscany, as you mentioned earlier, there was a lot of ferment in those years: who were the artists you were seeing, was there a debate among you, on what topics?

The ferment was the result of coming out of a period of “austerity” and the “lead years” of the 1970s. The 1980s was a period of renaissance from the point of view of creativity and beyond. It was the last happy period before the realization of total private and institutional digital control that we are now experiencing and would see implanted in our lives in the following decade. The world was analog mechanical and magnetic, artisans filled Italy’s cities, and in the suburbs manufacturing technologies were being innovated while maintaining a product of high quality and craftsmanship and wisdom. At that time I lived in Florence, had a studio in the Florentine countryside and traveled often to the United States where I also spent long periods. In Florence I was hanging out with artists of my generation and the previous generation who were somewhat suspiciously weaving relationships with the new. I worked in Rome in the studio of A. and B. where gallery owners, dealers passed by and we went together to the exhibitions of the artists of his generation, I would then meet at the openings the younger ones from the pastificio. From Florence I often traveled visiting exhibitions of artist friends in Bologna and Milan especially at gallery openings. In New York working for a time with the studio that produced Sol Lewitt’s works, I met some

few artists close to that world that revolved around Watanabe’s print shop where the color formulas of the wall drawings were designed. Debate among the closest artists was the glue of time spent gleaning the secrets of contemporary art while enjoying the spectacle of the end of the avant-garde and movements with a sense of heady, and often scattered, freedom. The artists were few, we could count them with the fingers of the hands of those present, we kept track of the works of the masters and artists of the generations before ours and tried to surpass them in mastery insight and inventiveness.

Yours was the first generation that was able to escape the burden of opposing sides and the politicization of culture and by virtue of this was able to move more freely among languages. Among the first receivers of these new instances are certainly Marsilio Margiacchi and Luciano Pistoi: how did you meet them and what relationship was created with them?

Subtracted or not subtracted we were and have always been subjected to enormous individual pressures, despite the alignments of the galleries and the stables of the critics in those years we tried to move independently as impatient splinters found possible and impossible ways to put our works on display. It was Antonio Catelani who one day pointed me to a curious moustachioed gallerist from Arezzo who would be willing to try his hand at young artists, who in those years were called emerging. Arezzo had always been a sleepy town nestled in the countryside, on the fringes of the tourist caravans that crisscrossed Tuscany and Italy, and had seen its first industrial development only in the early postwar period but allowed sharecroppers and peasants to become citizens and artisans raising the economic standard of the community. Together with a small group of artists, including Gianluca Sgherri with whom I had shared my Florentine high school studies, we started hanging out with Marsilio Margiacchi, who let us first clean out the gallery of its furnishings and then enthusiastically participated in planning exhibitions by opening collaborations with all the new artists there were in Italy. In that in-between period, before I landed in Milan, I had moved to the Arezzo countryside in an unusual rural industrial building, and I could follow the projects directly with Marsilio almost daily. In fact, with him we landed in Volpaia, in the heart of Chianti, where a community from Turin had settled and created an art hub. Luciano Pistoi in Volpaia prepared an annual event that opened the exhibition season, one of the first periodic artistic events that used the whole context of the village then involving the community in the final celebration and inauguration. People from the art world came from all over, critics, artist collectors, art lovers, journalists, gallery owners, students and art lovers. I participated in one edition in 1992 with intergenerational artists from all over Italy, and in those days we spent good days chatting with Pistoi and Margiacchi, about art and more, evaluating artists, planning exhibitions, and Luciano often attended the gallery in Arezzo.

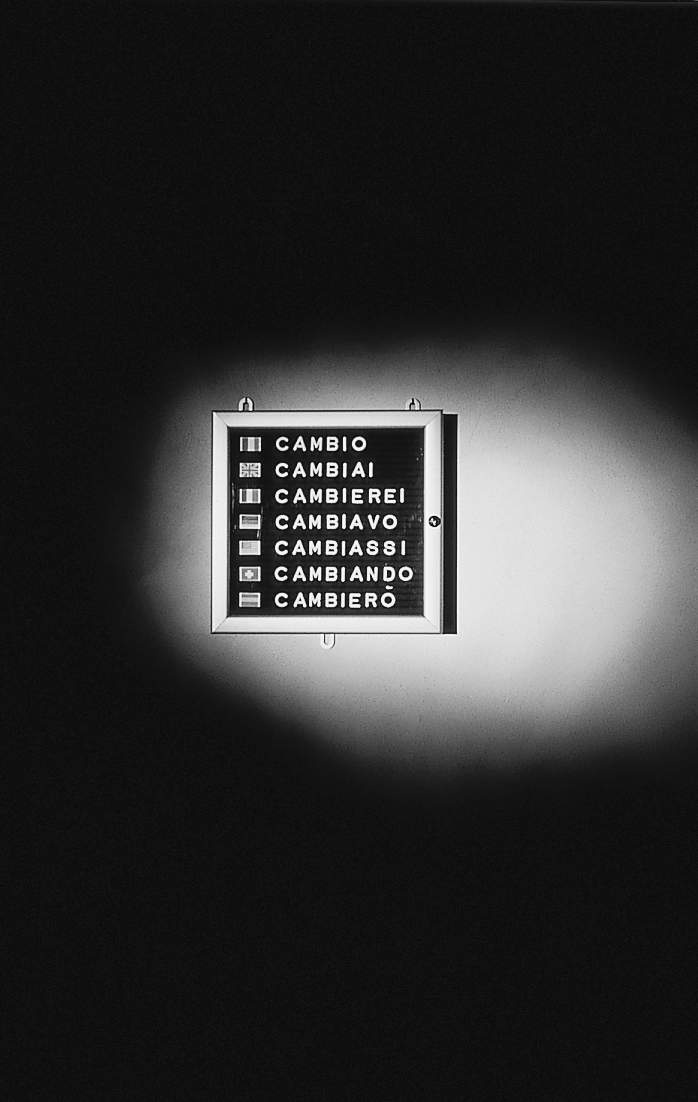

The first exhibition at Margiacchi’s presented by Maria Luisa Frisa was a group show with the symbolic title “Change,” a title coming from a work of yours published on the cover of the catalog. Besides Gianluca Sgherri in the exhibition with you there was also Andrea Santarlasci: what were the subsequent episodes of the Arezzo adventure?

The exhibition Cambio in pratica is an untitled exhibition named after the work on the cover chosen together with the other artists. This exhibition was a watershed for Marsilio’s gallery, which from that moment devoted more time to young new artists: this change necessarily involved the redefinition of the exhibition space to adapt it to the new requirements of formal cleanliness and absence of furniture. Only the brown carpeting survived for a while longer, only a couple of years later I also made a work of it during an exhibition with Marco Cingolani, a double solo show where I ideally flipped the floor to the ceiling and hung paintings there as well. Paintings that portrayed people in the previous exhibition portrayed as seen from above, from the ceiling. Maria Luisa was very present in that Tuscan period and particularly followed the group of artists close to Margiacchi’s gallery.In 1991 we exhibited in addition to Arezzo, in Florence in the Palazzo della Provincia, in Rome in the Sala 1 gallery, and in Milan in the Studio Corrado Levi and then she curated an exhibition project of mine at the Museo Marino Marini, in 2000. From1993 I began a collaboration with the Mazzoli gallery in Modena that lasted several years, and at the same time with the Continua gallery. The following year I moved my studio to Milan and many other things changed.

What is your work focused on these days?

Lately I’ve been working a lot on painting and drawing, as always I carry on cycles of work that often come from other cycles far away in time and so on. I follow a logical thread, which I then punctually lose, I try to have a path that punctually dissipates, I try to be consistent and punctually betray myself, I try to keep the important things in mind and punctually distract myself with futile, useless things, I try to understand what my making has produced and punctually distract myself in the interpretation by focusing on the particular, I try to have a consistent path and punctually betray expectations. This was the teaching I received and this is what I put into practice.

Is the archive a way for you to revive the mechanism of betrayal that you describe above?

The archive is a method, betrayal is a defense, if you want to introduce the topic of the archive I can tell you how some obsessions with various methods of appropriation turned into collecting and then archiving. Images are a heritage of humanity even if they are copyrighted. I collect and catalog them. I collect multiple subjects, select them and many I discard, some I license, liquidate, paint, or print them in all possible ways, imprint them in my mind. I collect, for example, stars from the 1980s, printed images with stars in them, details of flags, of medals on the jackets of generals and military men, of decorations on hats and in flags, in banners, and printed on the T-shirts of passers-by captured in the images I cut out, tear out, from any magazine or newspaper. Over the years the collection has grown, it has become a true Star System, a self-contained work. Stars are never missing in the images that are published, they are a true continuum in the photographic standard, they are all the rage in any period, military, terrorists, sportsmen, movie starlets, all proudly display them and bring them into my archive through their printed images As well as the images of stars, I have in the archive many other subjects divided by categories and themes, all archived in alphabetical order. Over time, the archive becomes a method, and it is fed automatically, it becomes a way of life that punctually leads to its betrayal, it is disavowed if it is cultivated, it is evaded if it is present, it is excluded if it is indispensable.

In addition to cataloging and collecting images that interest you do you also archive your own work?

Archive as an art form is one thing and archive as an organization of works and materials is another. A few years ago I founded A.L.P., Archivio Luca Pancrazzi, which is a physical place and collects all the works, photographic documentation bio and bibliographical documents, catalogs and everything around the works. It’s a space for photographing, cataloging packing and archiving.

Well, then going back to the initial episodes and taking advantage of the archive I wanted to ask you to focus on a couple of works among the early works by telling the genesis and developments in the later work . The first is the transparent pneumatic volume Collecting Space presented in Volpaia, and the second is the installation made on the ceiling of Galleria Margiacchi on the occasion of the exhibition with Marco Cingolani.

Collecting Space, in the sense of empty space, this was the original title and meaning of the work I constructed for the exhibition Spendente, in Volpaia, Tuscany in 1992.

I wanted to highlight the contradiction of the meaning of collection by talking about an object as impossible to possess as empty space. The work considered a portion of actual space within the hamlet, cutting it out, simply revealing and displaying it through an inflatable of transparent pvc constructed by tracing exactly the architecture of the internal volume of a pedestrian underpass that connected two small squares within the spontaneous urban development of the small hamlet. I was interested in that portion of the void between the two buildings that bordered it. That sculpture was but a revelation of the emptiness that surrounds us. In order to highlight it, I needed a shell to contain and delimit it. That project was the first in a series made through the use of the inflatable technique, which tried to carry forward the relationship between nature of the world revealed through a scan that, when flipped, would take into account the empty parts rather than the classical full volumes we are accustomed to evaluating. Reading in the negative scans the world to reveal what is hidden, but the voids tell us about the solids by revealing them as if we were seeing them for the first time. Volpaia’s work was a large clear pvc pipe welded with the shape of the underpass between two small squares. Custom-built, perfectly adhered, as soon as we inflated it I appreciated the unexpected effect of the sun touching it at either end, causing the light to run over the thickness of the pvc and ignite the whole tube with a reflected light that transformed it into a volume of ice. At that time I was developing in different ways the construction of forms and images from empty volumes and spaces, so even the wax sculptures within the Volpaia exhibition were but casts of empty forms duplicated to form new volumes. During the same period in Margiacchi’s gallery, in a double solo show, I was able to highlight another aspect of the space that surrounds us and that we inhabit. The exhibition was shared with Marco Cingolani, who used one of his themes of the moment to create a kind of pictorial sculpture, of an injured astronaut. In his work the subject was the cosmos, the space explored by astronauts, and it was particularly useful for me to play then with the idea of space, although in my case it was that of the gallery itself. An earthly space in relation to a cosmic space. The design of that installation stemmed from Federico Fusi’s previous exhibition in the gallery, where I was able to install a camera on the ceiling, remotely controlled by a remote control with which I photographed all the people with a zenithal point of view. Some who noticed the contraption looked up and I was able to photograph them in that unusual pose with their faces facing the viewer. I used the photos to make 11 pictures that I hung on the ceiling, not before stretching a brown canvas over them like the carpeted floor. A symmetrical, upturned space was created where then new visitors to the gallery during my exhibition would observe this upturning and become part of it. Often a subject would observe himself upturned on the ceiling. Space and time were the intermediate glue, the main subject of the exhibition, and simultaneously space became cosmic and the setting for the astronaut’s drama.

Space and time are two elements that have their own centralitỳ in your work and which you have interrogated in various ways over time. Another element that seems to me to have its own poignancy is the playful aspect that perhaps originates from the strong contact with A. and B.: can you talk about that ?

The twentieth century began with Einstein’s theory of relativity and marked the whole century, I was born in 1961, at the height of the economic and positivistic boom, questioning the certainties of one’s time was a linguistic mission and a daily practice of opposition to everything that was coming and was already the result of the worst lucid and cynical premonitions. Pop Art, conceptual art, and situationism belonged to us just as the worst post-transavant-garde painting belongs to young artists today. Every height has by its counterpoise its abyss, we were the last inhabitants of this planet to live by the day, putting a spoke in the wheels of the emergence of social controls since the dawn of electronics, our exercise was to dodge the frontality of the immense future that made the sky on the horizon black and funereal, but living by the day was, both the natural defense to maintain our freedom and the tool of opposition. Time and space were Einstein’s linear time and space. Space was infinite but not yet curved, and quantum mechanics, although born in the same century, a little later to relativity, had been challenged by Einstein himself and would wait for the new century to be better accepted, tested and popularized. The game, with its rules, was for me an exercise of intelligence, I was building from an early age, with my brother, new games using partly other things and the construction of the rules was the most complex and most interesting part, the game then served for its fine-tuning and verification. We played a lot, we lived in the game in our little room, in the same room that then, as soon as he moved to his new room, became my first studio, where I kept inventing and living in the game. Then the linguistic calembourms, the anagrams, the riddles, were part of the language and the way of continuing to play with art. They always entered more or less through the window and through the front door in my work and in that of artists with whom I often collaborated. The collaboration then with Boetti in his work certainly fortified this aspect and gave me the confidence to be able to continue to leave a privileged place for this practice.

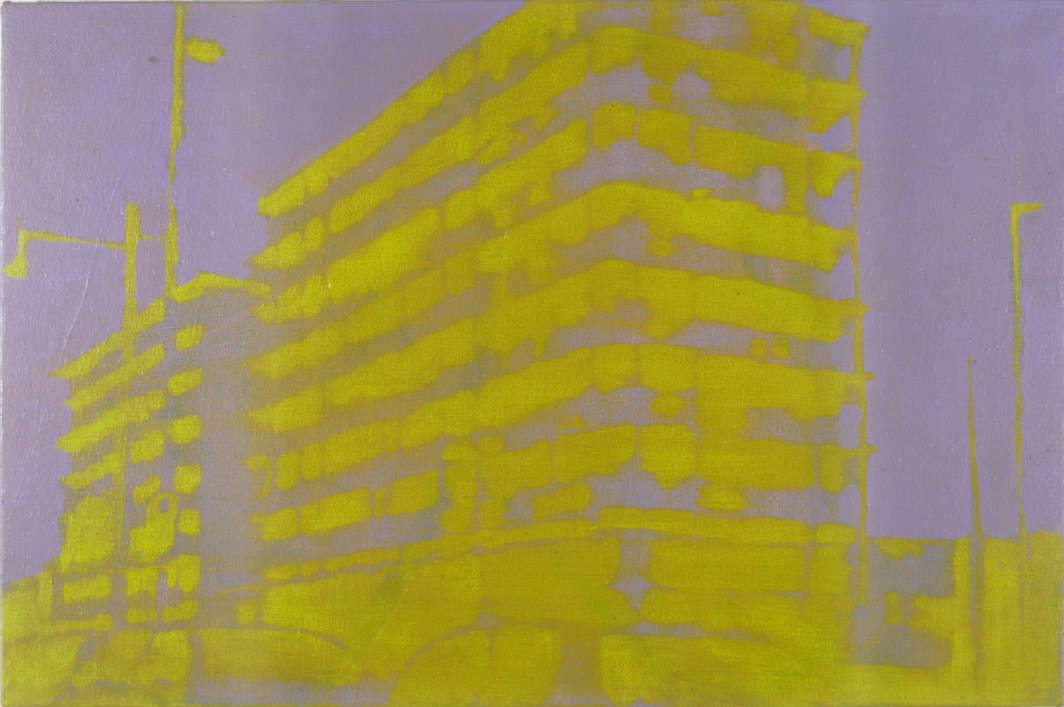

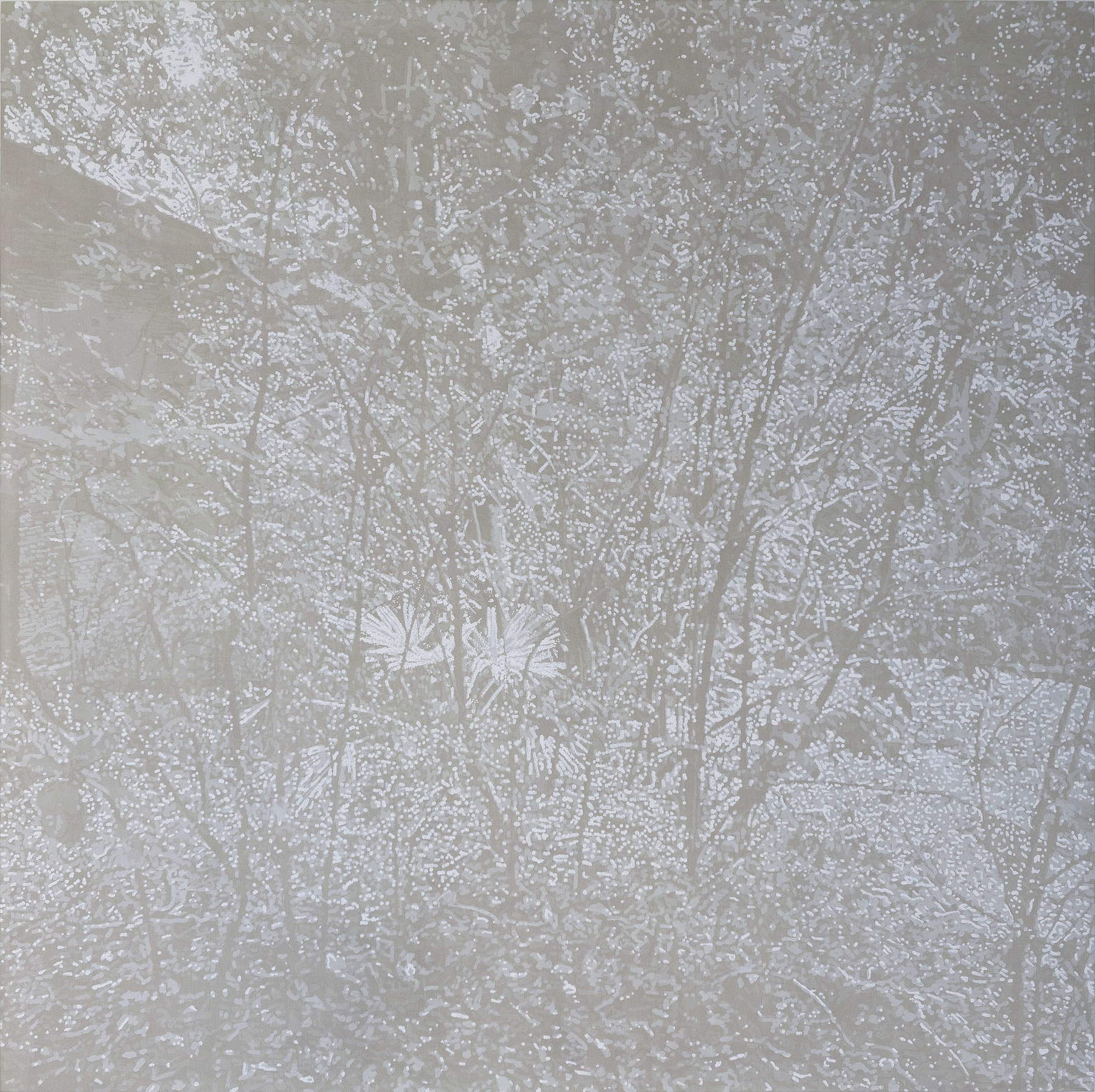

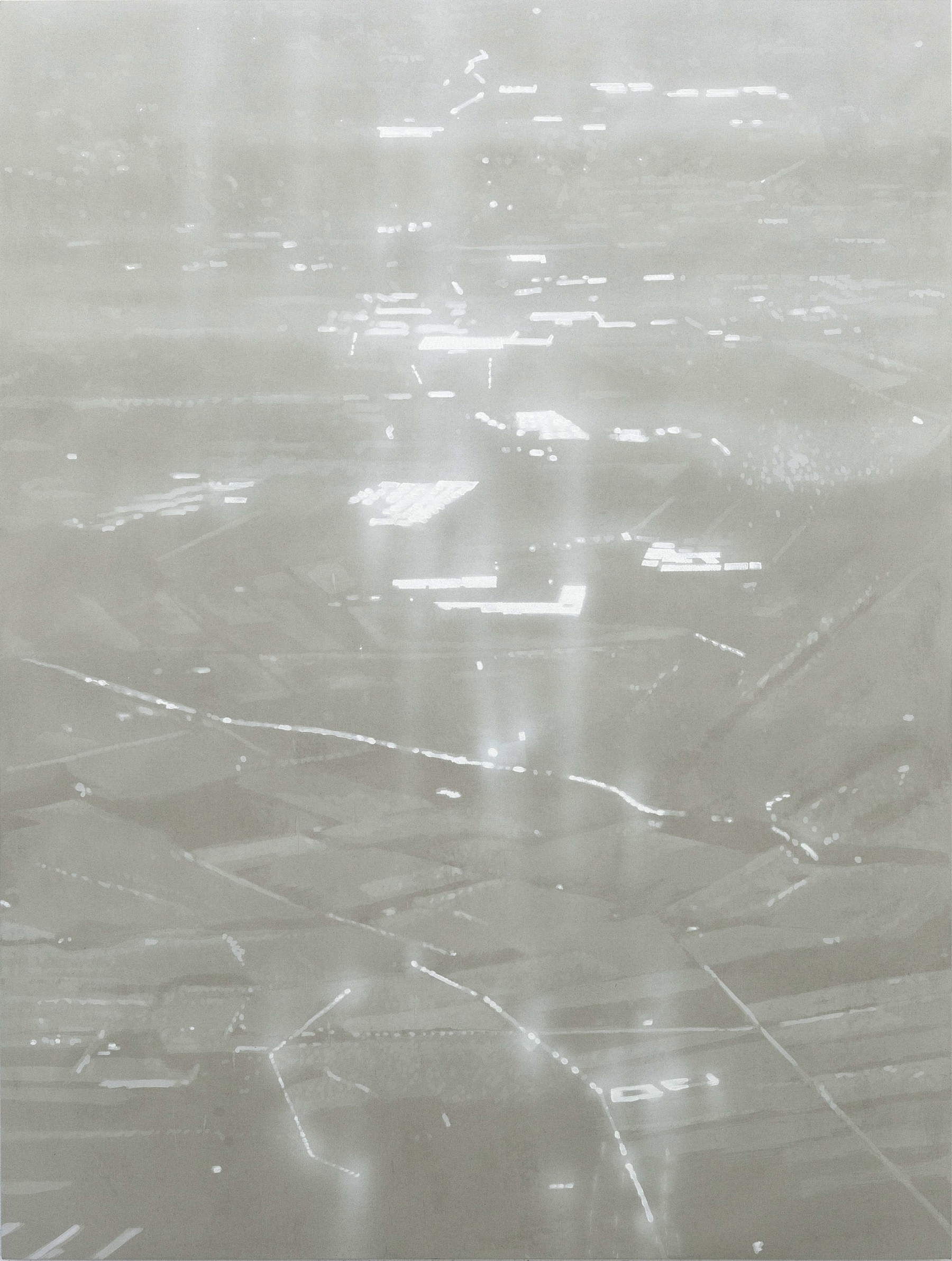

Earlier when you were talking about “Collecting Space” you dwelt on the description of light reflecting off the transparent material of the pvc volume, which inexorably refers back to painting another of the cardinal points of your work. I would ask you to go more into this aspect by telling, for example, how the white-on-white paintings come about and how this aspect of your work has developed over time...

As I seem to have always stated, I am an artist and painter, the retinal approach prevails in the art I make, even when I approach sculpture, three-dimensionality, but in this case I recognize that control becomes subtracted from time to time. The painting remains a kind of window, and even if the window were broken, smashed, without glass or with broken glass, or closed and the blinds pulled down, this window is the formal and conceptual comfort of the painting and is the main inescapable object to which painters refer, painting has always been the main Ring of art. This world inside the space of the gallery, inside the space of the city, inside the space of the world, triggers an inescapably fractal relationship by becoming the very subject of all paintings, in an infinite play of reflections and cross-references while remaining in a space that has limits. For the painter within that space is the possibility and ambition of control, or all that produces the setting of an attempt at control through the chaos of matter. The painter-artist presumes to be the creator of that chaos, responsible for its failure or success. But increasingly frequent and welcome are all those exercises in exiting the space of the painting that gradually cause the tendency to shift attention to the edges, of the sheet of paper as of the canvas, to the thickness, to the back then the painting rests on the floor, the sheet is thrown into the air, the canvas punctured, the surfaces are torn, the canvas is removed from the frame and reassembled badly, with creases and leaking abundances, the paint does not stop at the edge of the painting, it continues on the wall, on the floor, it goes out the door and strolls into the sidewalks, it expands on the facades and becomes gaseous coloring theair, and disappearing endlessly only to congeal with the low emotional temperatures to freeze again into three-dimensional forms, petrified or of liquid resinous memory, re-entering from the street into the front door or even out the window and then into the room. Control is lost to the super-casualty of all that cannot be controlled. This moving world borders the painting, convinces it to be included, sucked in, all those external elements are part of the total volume of what has become an installation. So painters have acquired, through widespread consciousnesses of this kind, this modern ambition to have necessity of control over the installation space of the exhibition, over the rhythm and the furnishing accessories that surround the painting, the baseboard, the floor, the light, of course, although we should not forget that painting is painted in another place where this neutrality is not there, painting if it is not site-specific, is born in the chaos of the studio, an organic chaos that the quartered artist spreads every day through his innards on the more or less prepared and disinfected canvases. So I also feel like a painter militarized by the reality of the world, but I mostly leave my ambition of total control over the space around me to cycles of works other than painting. I have always favored natural light because of the fact that it is never the same, that it progresses throughout the day, becomes warmer or cooler during the evolution between sunrise and sunset, suddenly subsides during the passage of a cloud, and returns the idea of time and precariousness with these cyclical changes. I love the modulation of natural light so much that to fully appreciate it I spent many years of my life working at night, using projectors to enlarge my images, so I could keep the windows open and appreciate the arrival of the dawn with which I ended my workday. Being in the dark trains the eyes to the little light and the brain completes the action of reconstructing the world even through just those few glimmers. From the blackness emerge the forms that are revealed through the light. So I began to paint pictures starting from the minimum, from the necessary, limiting the construction of forms through the color white, the color with which the lights are painted. The same white that is mixed with the chalk that is used to give a background to the canvas to paint on later. In that preparation space I started and finished the painting, which at that point leaves the darker parts visible through the lack of paint. The natural canvas is then the background tone, and by diluting the pigment in homeopathic doses I made landscapes and still lifes. My latest New York exhibition whose catalog is out now, after more than a year, has light as its subject, the title Flash Light forces the aspect related to this depiction, bringing it toward the glare, the reflection, the contrast, that light procures in some cases.

Here, the idea of glare brings to mind another work of yours, that of the Maserati covered with fragments of transparent glass, a practice you have also exercised on other objects (clocks, chairs...) that are part of your iconography. Do these works also investigate light?

Everything investigates light, even darkness. The cycle of works that have the ending “rundum” allude to the material carborundum, hence the title (car)borundum can easily be deduced, and it was inevitable that the first work in this cycle was a car. I wanted it to be traveling and it traveled around Pescara the first Carborundum in 1996 during an “Out of Use,” it traveled inside the exhibition and outside in the neighborhood across the street. With this first work I applied the technique that later served for the works in this cycle. I thought of covering the car with shards of shatterproof glass from the cars themselves. I wanted a glass grit that would simulate on a macro scale the function of an abrasive and at the same time luminous material. The work had to be as abrasive as the carborundum used to make abrasive sheets and materials is, and it had to reflect light as glass can do to break up the compact form of the object and fragment it with reflections just as my white paint produced to the shapes it represented. Splinters of abrasive light. Just as the abrasive cover of some Guydebridean situationist publications produced the effect of consuming the nearby books whenever it was taken out and reinserted in the bookcase, so my carborundomized car, passing through the city, would smooth out, wear away all the corners and roughness making things and houses smooth. During those days in Pescara, a rain and wind storm ravaged the outdoor warehouses of large glass companies in the area. As a result, I was able to tap into an unimaginable amount of glass, free of charge, but more importantly, I was able to choose from the various shattered batches. I thus deviated from the initial plan of using shatterproof glass by switching to the far more threatening shards of clear glass. I favored glass with large thicknesses, and of super-clear glass, glued to the car in a decidedly more dense manner than glass placed on the culminations of low walls to make them impassable. My Regata turbodiesel was beautiful, the best customization I had ever seen, so I told Lapo Elkan one night in a bar in Florence.

Did he provide you with the Maserati?

No, Jean Todt kindly provided it to me, when, asking for a Ferrari concession, even just its body, painted red, with wheels, he instead diverted the request to a new, traveling 4-door Maserati. I then changed the design for the Moscow Biennial from red waste glass from Murano to thick American superclear glass.

Here, I wanted to ask you to talk about the importance in your work of playing with the scales of reproduction by going from 1/1 to micro the landscape for example.

Just to go from pole to pole... I think you are mentioning 1:1, my exhibition within the Moscow Biennale for the 2007 edition, and in the same question you mention the cycle of sculptures dedicated to the horizon that in some cases manifested itself in the form of an architectural column with a landscape inserted at eye level... What to say about that? Play is a beautiful thing to be able to enact; it is the engine of making and unmaking. In juxtaposing different scales coexisting within the same work I enact vertigo by making it impossible to see the work, disguising it with the actual architectural scale and at the same time imposing such close observation where the context disappears. The observer must actively place himself in relation to the work and in relation to the space. The space appears empty, there are walls a floor, and there are columns. One of the columns appears strangely cut and one approaches it to get a better understanding, the cut is right at eye level, but how could a column have been cut? What is inside that cut? You have to get so close that you attach your eyes to that cut and eventually we are looking at a landscape, a horizon that evokes a landscape, so we are looking through the column itself and we see the space beyond the cut, beyond the column. The fruition of space is to move through an empty architectural place, while at the same time an image of a landscape on the horizon has formed in our minds. The work The Landscape Watches Us is made of this imbalance and vertigo. If we look deeper, we find that the landscape is made of small fragments, objects resting on a plane, on the plane of observation. A nail, a bolt, a box of pins, a pencil sharpener, a calculator keyboard become buildings, water towers, smokestacks, factories, constructing a landscape that belongs to a common vision conjured with a few found objects. Nothing is constructed, the objects are glued into the gap and the three-dimensional landscape is visible from all sides of the column by turning around. What is the landscape? What is it made of? Does the person observing it change the landscape itself? Do two different people looking at the same landscape see the same things? Looking far into the horizon has always been a good exercise for the eyes and the mind.

Very often the urban landscape is the protagonist of your works what attracts you to these non-places?

Urban landscape does not mean non-place. Ever since Marc Augé analyzed the presence in the landscape of spaces with reduced relations, called non-places in his essay Non-lieux. Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité (1992), we have become aware that diffuse anthropization is the characteristic of our planet. The urban landscape is one that I frequent on a daily basis; I have learned to read the transformations, and the nuances, in the city that I pass through, going from one center to another by traveling along privileged infrastructural channels that connect all the centers seamlessly. I think the non-places that you identify in my work are the paintings that represent corridors and spaces of communication between places. I started painting corridors because they did not have their own artist to represent them, and enhance them. I was the first painter who worked trying to represent relational rarefied spaces, that is, all those anti-pictorial places that we use every day without giving them a representation. Many of those paintings were actually not really non-places, but simply places of passage, of exchange, of interchange. These paintings have the general title that collects them “Interior,” so they are for me an homage to oil painting on panel, an interior work to painting, a painting that represented architectural interiors. Over time, this iconographic choice slipped toward those spaces described above, which came initially from stolen images, from catalogs of office paneling and modules, of prefabricated and laminated construction, of glass and interior partitions of a certain international modernism. The paintings called “Interiors” for a brief period could be identified with the term coined by Augé, but before and after that transition they were and have become anything else, even for certain cycles even still lifes painted live in the studio. This poetics of certain spaces in rarefied relationship then continued in the pictorial representation of roads and highways depicted with a central, symmetrical view, and then with the series of tunnels and bridges. The urban landscape, on the other hand, is anything but a non-place, at most as far as the suburbs are concerned one could speak of places tending toward anonymity, a certain degree of sameness, but they are anything but non-places, I would say they are places par excellence, spaces of human tragedy that can evoke everything we need when we project ourselves into the vision of a landscape. This could be the sense, there is sacredness in anything we observe, it depends with which eye and willingness one observes.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.