Love in the time of digital art. Interview with Kamilia Kard

Kamilia Kard is an artist and lecturer born in Milan in 1981. Her artistic research explores issues of human perception in the context of hyperconnectivity and digital communication. After graduating in Political Economy from Bocconi University, she embarked on an artistic path, obtaining a diploma in Painting and a degree in Net Art from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. She was also a doctoral candidate in Digital Humanities at the University of Genoa and currently teaches Digital Applications for Visual Arts and Multimedia Communication at the Brera Academy. Her investigation focuses on the influence of new modes of online communication on the body, gestures, emotions and feelings. His works traverse different expressive languages, from digital painting and video installations to three-dimensional sculptures, AR filters and interactive virtual environments. Among her best-known works are 2017’s Woman as a Temple, 2020’s Compulsive Love, and Toxic Garden, the latter an ongoing online participatory experience that reflects on toxic human behavior within digital worlds. Kamilia Kard’s works have been exhibited internationally at venues such as the Milan Triennale, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Museo del Novecento in Milan, and the Fotomuseum in Winterthur, Switzerland. In addition to his extensive artistic production, in 2022 he published the book Art and Social Media. Generators of Feelings, which explores the relationship between digital art and social media. In this interview he talks to us about his art. The interview is by Noemi Capoccia.

NC. Kamilia Kard, you are an artist who has been working with digital for years. We talk about works that have to do with 3D modeling, animated gifs, interactive virtual environments, and AR filters (your own website is a dynamic painting). Why did you decide to use new technologies as a medium for your art?

KK. I don’t remember a real moment in which I decided to use new technologies, it was rather a journey that led me to experiment with new techniques and analyze new languages. It is a journey that I do not consider concluded, and one that continues to fly me between different artistic techniques, from digital and ultra-contemporary to traditional ones. If I really had to pinpoint a representative moment that marks my transition to new technologies, I would say it was my interest in the involvement of the viewer in artistic practice. This interest led me to hypothesize works such as websites, collaborative projects, augmented reality filters, and virtual environments. In net art works such as Free Falling Bosch (2014) and My Love is so Religious (2015), the viewer scrolls through different scenarios and compositions through a simple click; in Best Wall Cover (2012-2014), he creatively contributes to an online archive; in Loading Instructions (Mansplaining) (2021) he plays the character in a video game. Another reason that led me toward the use of new technologies was the sociological impact they can have on people and, consequently, on art. The study of technique is thus the consequence of theoretical scientific research that I was interested in pursuing, and vice versa: practice leads me many times to theoretically deepen certain aspects. A recent example are my reflections on AI in works such as A Rose by Any Other Name (2021), where through the creation of an animated 3D model-and then made available on a website for interaction-I hypothesize the difficulty of reading theartificial intelligence, imagining it incapable of recognizing hybrid forms, such as roses that move like animals (minnows), which have a material similar to human skin, on which are applied girly tattoos, some of which bear the words “I’m a daisy.” A confusion of form, movement, material, and language that makes it difficult for the AI to pigeonhole that specific object by following specific tags, data, and biases set a priori. Instead, the funny thing is that if that kind of hybridization were required in a text-to-image program, the AI would do it without a problem.

Her work explores the issue of online communication and how these connections have influenced emotions, feelings and their perceptions. In your opinion, can this different and certainly innovative approach redefine interaction in relationships, both online and offline?

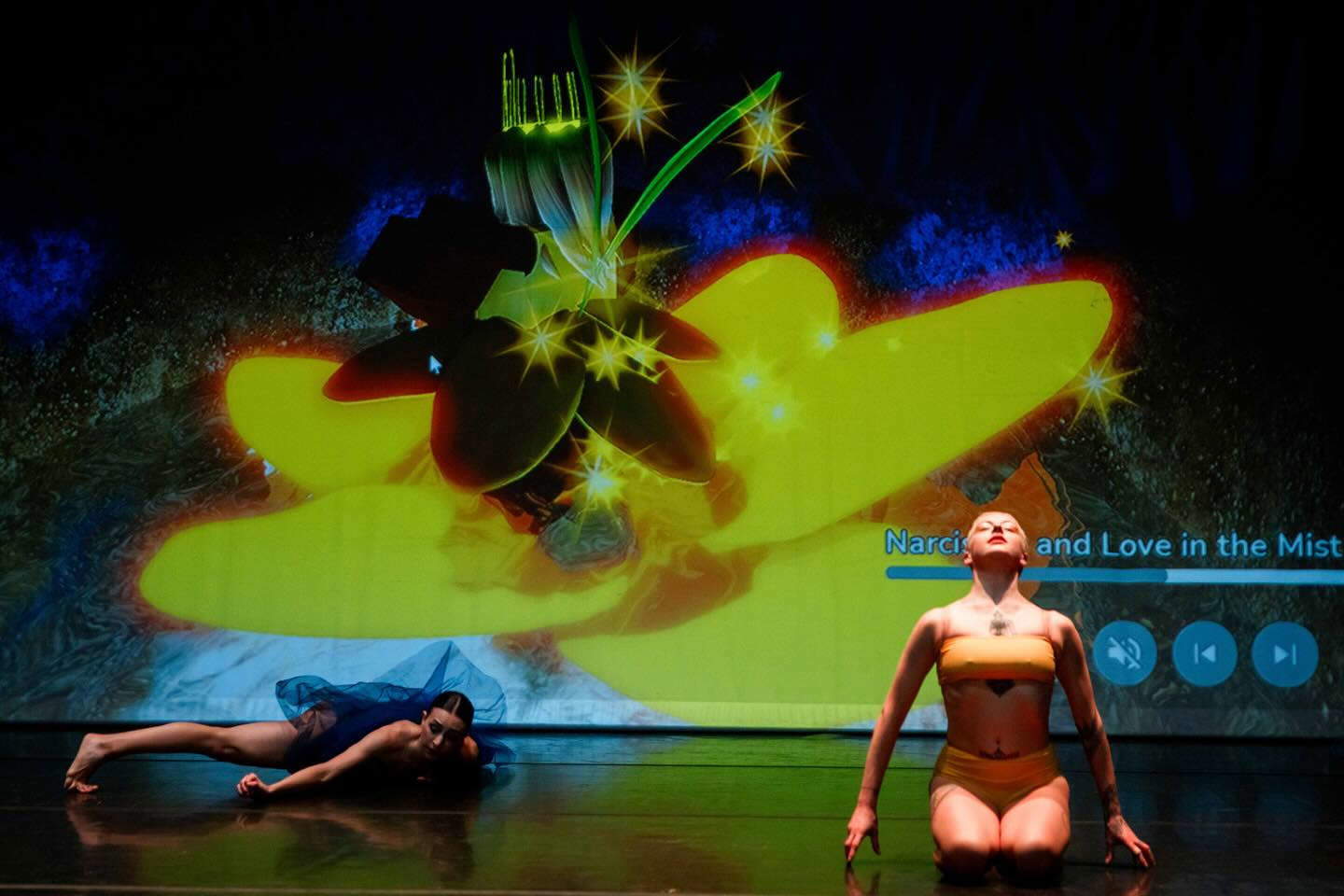

Yes, without a shadow of a doubt. The use of online communication and social networks has facilitated interpersonal relationships in terms of accessibility and reachability, but at the same time, the constant findability of people has introduced a number of new issues in relationships. We can say that we lose our minds if we are left with an unanswered “viewed” for too long, for a green dot that alerts us to a user’s online presence, for one too many likes on the “wrong” profile, and so on. We live very intensely what happens on our device. We can fall in love simply by texting a person, even without ever having met them, establishing relationships that often exist more in the imagination of those who experience them: imaginationships. Then, at the opposite end of the spectrum, there are applications that aim at facilitating live dating in a serial way. These applications express in an even too obvious way the accelerated pace of life to which we are subjected, which leads us to have continuous starts and losses even in romantic relationships, and highlight a tendency toendless scrolling or swiping, looking for the next match. A couples game similar to a large-scale slot machine: “who knows if the next one or two will be the right one.” And if not, all the better: the “human case” on duty will immediately be turned into a meme with social testimonials spread on other social networks. However, even the live encounter procured through an online application will return through sharing the experience in the online sphere. An egoriferous love, a consequence of the new forms of narcissism provided by hyperconnectivity. It is no coincidence that one of the most frequent tags in online sharing in recent years, when talking about failed relationships, is precisely “pathological narcissism,” used and applied to everyone and everything even when there are no professional or pathological prerequisites for doing so. Yves Michaud, in Narcisse et ses avatars (2014), had anticipated and described the new Narcissus as a person no longer content to admire only his image in the mirror, but with a need to share it and create consensus around it. A rather insecure Narcissus, I would say. Of course, there are also relationships that have positive outcomes - or at least I hope so - but these do not generate the same echo of sharing and consensus as do the tragic and cringeworthy ones, which are more apt to go viral, to generate views and memes. In this sense one confuses the figure of the Narcissus with that of the victim; both behave in the same way. One of my very latest performance works in the Toxic Garden cycle (2022-2024) - work whose theme is toxic relationships - titled Narcissus and Love in the Mist (Narcissus and the Bridesmaid) is about the impossible relationship between a person with a strong ego, focused only on himself, and an introverted and weak person, dependent on the affection of others. This performance combines dance in the metaverse with dance on stage (in the theater), creating a choreographic dialogue between avatar-spectators-dancers online and dancers on stage. Thus, a relationship that takes place on two planes: the online and the live. In this work I used two flowers, the daffodil and the scapigliata damsel, to represent the subjects on stage. The daffodil flower, for obvious mythological references of behavior, and the scapigliata damsel, because it is a flower whose blue-petaled corolla stays closed, wrapped by leaves resembling small needle-like nets, and opens only with the help of an insect that comes to solicit it. This floral choice is a metaphor for two different human attitudes, both of which should be considered problematic.

If we think of Compulsive Love, Belladonna Be Careful or Falling Love, these works all have a common interest: the female body, love, feelings and emotions. Where does the need to talk about these themes come from?

Very often I deal with the theme of love in an explicit and central form or as a secondary subplot. For example,in A Rose by Any Other Name, the title is a famous quote from the Shakespearean tragedy Romeo and Juliet, one of the quintessential (toxic) love stories. Also in that work, roses assume affectionate gestures by exchanging “kisses” and tenderness. So, although the main reflection of that work was something else, love is one of the recurring themes that I almost always include in my works; the same thing happens with the research on the female body and the condition of women. The video installation Compulsive Love (2019), made site-specific for EP7 Paris, enhances the idea of extreme, impossible, and harmful love. In this work I first quote Romeo and Juliet remediated and recontextualized by Baz Luhrmann in the famous cult film Romeo + Juliet (1996). In a nutshell, I create a composition of frames from the film to which I apply glitter effects; the latter emphasize the expressions of desperation of the two protagonists and the instrumentalization of love, seen as a weapon, narcotic or capitalistic expression. There is also an Instagram facial filter of this work that applies glitter to the people who use it that follows the path of tears in Leonardo Di Caprio’s close-up when he thinks his Juliet is dead. The filter is a chance for mass sharing of one’s image and a state of mind related to the failure of glitter-toned love, such as the impossibility of selfless love for others. In the facial filter Falling Love (2021), on the other hand, I use the instruction send a kiss as a fundamental gesture to succeed in playing the video game. In this AR filter, the action of sending a kiss-often associated with the emotional sphere-becomes a mechanical act to succeed in winning love points. Here, love is quantified in a score and sentimental gestures are used as triggers for the experience, in an attempt to understand how our expressions and emotions are exploited and stored to better profile us and offer us personalized content. A kind of continuous mirroring that feeds and fosters the various new forms of online narcissism. The diptych video Belladonna Be Careful (2022) consists of two flowers of beautiful women made in 3D that rotate on two backgrounds of different colors: one blue and the other pink. Two faces of the same love-person: one positive, with realistic and natural colors, on a blue background, the other poisonous, with iridescent and unnatural colors, softened by a pink background. Two aspects of love associated with the fragile and dangerous figure of the beautiful woman.

How does contemporary society influence the way you represent themes in your works?

I have always liked to observe people’s behavior, trying to define their repetitions, excesses, insecurities and so on. Mass online sharing of disparate content, from selfies to statements, from links to game sessions to moods, gives me the opportunity to pause and study certain attitudes on a large scale. I generally observe phenomena occurring on the web, trying to go on to understand then how these create entanglement in the non-online, non-digital experience.

Your latest and current cycle of works is related to the plant world and toxic love. How do you explain this choice?

Toxic Garden - which I mentioned briefly earlier - is a project that combines video games and performing arts within a metaverse created by me and composed of poisonous flowers. In this context, I used the metaphor of toxic plants to express harmful human behaviors toward others. Hypothesizing a kind of ancestral remnant of plant component that influences human beings when they feel attacked or activated without reason. This mixing of plant and human is echoed in the environment avatars that are hybrids between plants and stylized blocky human representation. This form of hybridization stems from the need to break down barriers of gender and race, promoting inclusivity as much as possible and creating a community that reflects on the issue of toxic online and offline relationships. The toxic plants, in addition to representing the player-actors who take part in the performance (or who enter the part of the game that remains public even when there is no performance), also form the main garden of the metaverse; each of these plants is associated with mini-games inspired by the harmfulness of the plant. In this context, the set of plants converted into infrastructures on which the avatar can climb, play and dance, represents the social architecture, container and creator of a whole series of feelings and emotions expressed in my project in the form of emotes: small animations of the avatar expressing a state of mind - a very common tool in Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO). To create the toxic garden emotes I collaborated with 4 dancers, who after reflecting on the topic of harmful interpersonal relationships identified with me a set of keywords that became triggers for the creation of the dance step and at the same time the textual name of the emote available in the video game. Precisely during the process of capturing the dance steps with the dancers I made using artificial intelligence (AI), I was able to observe how the AI’s mistakes were an interesting component of the movement and from this reflection, and the use of the 3D models of the toxic plants I had modeled for Toxic Garden I developed the project HERbarium dancing for an AI, a performance that combines live dance and projection and is divided into 3 acts: Love Potion, Death Potion and Dream Potion. HERbarium addresses the themes of the role of women, the witch, romantic relationships, plant behavior and artificial intelligence. In fact, the concept of HERbarium - Dancing for an AI stems from the association of woman as a witch figure - an age-old image - and AI as female entities, a recurring theme in film, fiction, and everyday use, as evidenced by Siri and Alexa voice assistants. In films such as Spike Jonze’s Her or Andrew Niccol’s Sim0ne, AI is portrayed as female, and humans develop a toxic addiction to or undergo manipulation by these figures who might be called “digital witches.” These entities seem to have the power to make humans lose control, who become succubi to them. The witch, historically, has always been seen as an evil female figure, capable not only of creating spells, but also of cursing humans through physical transformations and the creation of deformed beings, part human, part animal. Poisonous plants, linked to witchcraft, were used to produce poisons, love potions or hallucinogenic substances. With HERbarium, I wanted to explore this parallelism by imagining AIs as modern “digital witches” capable of altering emotional dynamics and manipulating the human mind, using a new form of power that, just like the poisons of yesteryear, has the ability to intoxicate relationships and create psychological addictions. In this performance, the error component of AI is central to the concept of the work. In fact, these movement processing errors are transformed into an opportunity to learn and interpret an expression of the body that does not exist in nature, an unnatural movement. It is in these misreadings of gestures that the AI manifests her “creativity” in dance steps, transforms herself into a choreographer manifesting a form of authorship. In AI’s freedom of movement and the idea of AI as a witch capable of creating hybrids between different species, I built my idea of AI-mediated movement as an opportunity for human and technology, technology and plant, human and plant to meet. Yes, because while the dancers were learning the choreography repurposed by the artificial intelligence-that is, including all the movement errors-they could not help but also follow the movements of the plants (which in turn moved with the same choreography assigned to the dancers, adding several errors dictated by their anthropomorphic plant nature). So, if in the end the plants in the background moved due to human movement mediated and digitally transformed through AI, the dancers in turn danced a choreography that encompassed AI and plant movement. AI-mediated movement and reproduced error become in my work an important glue between human, plant, and digital, a creator of ontological uncertainty that opens up infinite possibilities toward a broader knowledge, a rapprochement toward the nonhuman; an element that creates a hybrid that underscores and gives greater value to the concept of the project and the idea of AI as witch. In conclusion, in my performance a continuous dialogue is established between the machine and the human. The process begins with the dancers creating steps, which are processed by the AI. The latter then returns a new choreography to the dancers, generating a cycle that enriches human movement with a technological vision. It is not a matter of making the dancer automatic or humanizing the machine, but rather exploring that uncertain boundary between the two, blurring the human-machine dichotomy and creating a “vigital” (digital vegetable) dance body that amplifies this interaction.

Your art is not only visual, but also immersive. What need drives you to want to interact with the audience?

I like to make the viewer the protagonist of my works, for better or worse. I do this through video game simulation, large projections, asking them to participate in online performances or, as I explained at the beginning of the interview, engaging them with a simple click. The denial of the unique and central point of view of the artist in some cases, and the direct experimentation with a certain feeling are two of the main reasons why I engage the audience personally. In Toxic Garden Dance Dance (2022), a participatory performance on Roblox, the avatar spectator at one point dances the same choreography that the other avatars of the spectators participating in the performance dance. In this uniformity of movement, environment, and avatar customization, what makes the viewer’s experience truly unique is the point of view, which is unconstrained by the artist and one-way. The viewer will experience the experience subjectively or by following their avatar, they can walk around and move through the space. The theatrical constraints of frontal viewing of the work are also lost. While in Loading Instructions (Mansplaining) (2021) I try to make the viewer experience through the simulation of the video game a specific state of mind related to the concept of the work, the sense of defeat of those who find themselves fighting against the rubber wall of a macho society, in which women lose even when they win or are endowed with obvious superiority.

How doesyour art, which combines aesthetics such as kawaii and curvy models , manage to converse with today’s audience?

In an age dominated by kawaii - or cute - and the power this uncertain aesthetic wields over contemporary society, my work often addresses important issues, such as toxic relationships and mansplaining, with an aesthetic that tends to lighten the viewer’s load of the subject matter, allowing them to enter into dialogue and understand the work in a more effective and fresh way. The cute perturbing is for me like a kind of pink filter that gradually fades into orange applied to reality. Something that attracts me but also frightens me. For as long as I can remember, the last few decades have been dominated by the kawaii aesthetic, in a kind of cute monologue. Hello Kitty has become over forty years old, a mouthless kitty with round shapes and dot eyes, Sanrio’s winning product that has captivated generations and generations around the world. There are some cute shapes and colors that are recurring, such as pastel colors-unless we are talking gothic kawaii-and as I mentioned earlier the gentle lines of the curves. The cherubs and angels might be an early form of cuteness ante litteram: how many of us going to the Uffizi in Florence have not been gently and tenderly entranced to see the sad, dreamy gaze of Rosso Fiorentino’s Musician Angel (1521) playing a lute larger than himself? What is it that engages the gaze and the spirit so much? It is the boundary of uncertainty that creates the contrast between the angel’s soft forms, forms in this case associated with the funny proportions of the child figure, and his attitude, his sad expression that makes him so pleasantly nostalgic and cute to us. Contemporary generations experience a continuous state of uncertainty and precariousness spread over many levels; the spread of cute on such a large scale is a great expression of this, or perhaps a refuge. In works such as Woman as a Temple (2014-2021), in which I exalt the curved forms of women, celebrating their universal maternal beauty, I use a tendency toward cute. In fact, my sculptures have very common colors in Kawaii aesthetics, as well as recurring shapes. At first glance, people who see my sculptures want to touch them, some to hug them. They seek contact despite the fact that they are in fact women’s bodies without legs, arms and heads, something that should be monstrous. Or this is the case with the aforementioned Toxic Garden, in which the cute aesthetic of the rounded cubic shaped avatars and the colorful environment are a triumph of the cute, which instead conceals a difficult and complicated issue of toxic relationships. Like Hello Kitty, Toxic Garden avatars have only eyes (in different neon colors), made as simple, small ovals with a glow around them.

Although pink is the predominant color in her works, toxic loves, superiority of women, eroticism and glitter are part of her artistic journey. What drives you to depict such colorful worlds and dreamy atmospheres that actually conceal much deeper messages?

As I mentioned above, this choice stems from a desire to send an important, sometimes problematic message in a simple way. I try to make the audience think without further burdening them with heartbreaking aesthetics. Loading Instructions (Mansplaining) (2021) is an example of this. This work is a machinima video shot within a video game I developed, Zero EXPerience (2021). The video game is a single melee (hand-to-hand) combat scene in which a female warrior equipped with a pink sword and shield faces a man completely unarmed and in his underwear. Despite the woman’s superiority in skill and equipment, the man in his underwear will always win. The machinima uses the gaming language of in-game instructions found in RPGs: while you wait for the game to load, static or minimally animated images appear accompanied by hints or instructions useful in the course of the game, inserted as subtitles. Somewhere between irony and denunciation, Loading Instructions (Mansplaining) sequences typical phrases of the “mansplainer” in the form of hints and tips to satisfy his game. Some of the phrases included in the video are responses to a call about mansplaining that I had posted in Instagram stories. The work expresses the state of powerlessness and psychological vulnerability in which women are often confined, in the workplace and otherwise.

In a world that sees women as objects of male desire, you have reversed the process of commodification of the female body. How do your Venuses approach those of ancient art and how can they relate to each other?

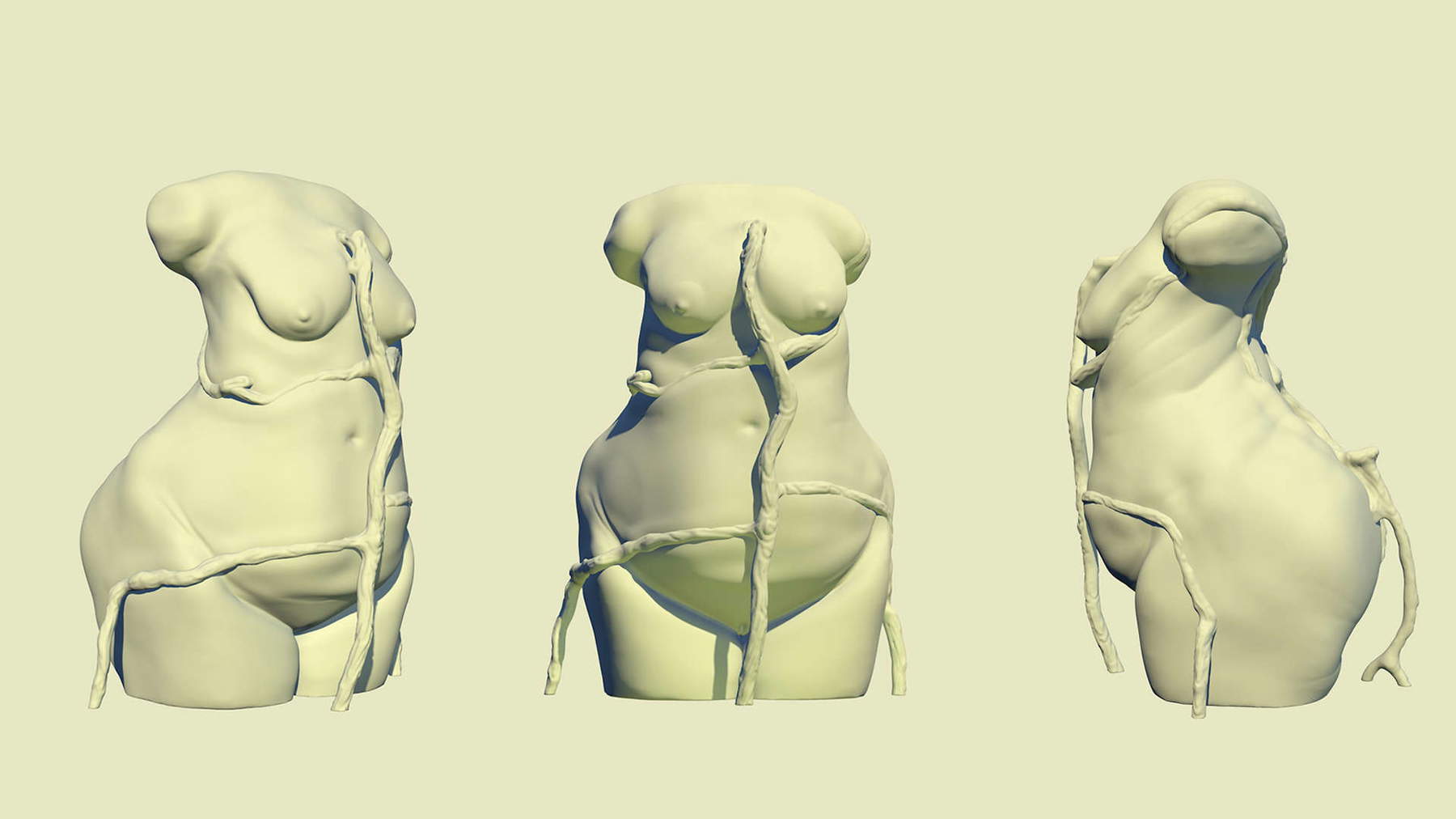

The sculpture series Woman as a Temple (2016-2021) takes the voluptuous female body and shows it in all its naturalness and statuesqueness. They carry with them all the sacredness and abundance typical of Paleolithic venus but are redefined in the absence of limbs and head. They become anonymous bodies, recognizable only by their central part without somatic features, without race. They are the inescapable and unique center of women, the strength of their matriarchal being and the source of their weakness. They are an exaltation of contemporary imperfections, defying contemporary aesthetic standards. But it is also a very stable body, from security it is welcoming, a temple. I chose 3D printing to make this cycle of sculptures because I like that you can see the layering of the print, those overlapping layers of filament remind me of the layers of the earth’s crust and also the circles of tree trunks, as for the latter two things those marks indicate the life cycle of the sculpture. For this reason, I do not “correct” my prints, but instead choose filaments that enhance volumes and defects. I also like that the woman’s body retains the errors of the printing process; marks that represent on the one hand the problems the sculpture had during its creation, but on the other hand evoke the visible and invisible scars that accumulate over the course of a woman’s life.

What is the ultimate goal of your art?

I like to observe how certain social phenomena influence people’s behavior and try to interpret these influences and sharings according to my own point of view and with my own stylistic signature. For example, lately I have been working on a new series of sculptures made with a 3D printer entitled A Love Story as Many Others(2024). This project tells how romantic relationships, which we experience as unique and special-in the positive but mostly negative sense-are actually clichés resulting from the repetition of human behavior. This conception is exalted and taken to the extreme through the sharing on social networks of videos, audios, screenshots of messaging conversations, of sentimental love affairs, partly to make fun of each other, partly to seek a community that shares the same experience. Very often, when a video has the right audio or mood, it is either re-shared - or republished - as if it were one’s own experience, or reinterpreted by the users themselves; keeping the same audio and working with lipsynch, or making the similarity explicit with text, giving further tone of collectivity to the affair, which gradually takes on characters of familiarity more and more ingrained in our everyday life. Building on these observations, I chose to model different torsos of women to emphasize the choral multitude of people living “the same clichéd love story,” and the roots that embrace and imprison them are the visual translation of hashtags and recurring words that are very often found in these video shares, reinterpreted using metaphors: hashtags such as #lovebombing or #ghosting, to which the names of the individual sculptures wink. Women, as I pointed out earlier, are always at the center of my investigation, and although there are also many videos of men addressing the same issues from their own perspectives, I chose to focus, as always, on the female experience.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.