The problems of Venice as seen from the eye of the main point of reference of the Catholic community in the lagoon city: the Patriarch of Venice, Monsignor Francis Moraglia (Genoa, 1953), who has held the Patriarchate since January 31, 2012. A dialogue on the overtourism plaguing the city, on policies to stop it (in particular the hypotheses of a ticket or of a closed number), on the depopulation of the historic center but also on issues related to cultural heritage, on all the entrance fees in many churches in Venice. Also, topics of a more strictly pastoral nature.

AL. As a pastor of a thousand-year-old community, what do you think about the gradual depopulation of lagoon Venice for the benefit of tourists who come only to visit and not to live? Can a Church as a museum live without a people who have a lived experience of it?

FM. The constant depopulation of the city of Venice (I am referring to the historic center and the islands) is a fact that structurally erodes the community and, in the end, undermines its existence - which demands a continuous and concrete turnover - and it is like that for the life of the Church as well. However, I would not reduce the issue to just the resident-tourist pair. There is, in fact, also a large student “population,” with presences of young people who give life to a semiresidential form by integrating themselves, albeit temporarily, into the life of the city. The same happens for professional categories and with multi-year assignments in Venice. Moreover, tourism itself knows levels that differentiate it with fleeting but recurring presences.

Venice today is a world tourism destination because of its uniqueness in the world. It is something to ’see’ regardless. A world attraction that makes problematic what for others would be a source of wealth: the tourist. What do you think of proposals to ’curb’ the problem such as closed numbers for non-residents?

Limitations such as closed numbers or forms of taxation on entry could be discriminatory, difficult to implement, and, I believe, cause difficulties for the resident population in their relationships with friends and relatives who would have the right to travel to Venice to visit and meet them. Such measures could, yes, provide for a number of exemptions, but with not a few complications, especially in the verification mechanisms. In addition to these organizational difficulties, which local governments would certainly have to evaluate, there remains concern about the psychological impact that any filter measures in entering and leaving the city might have on the resident population and external perception. In the end, it would contribute to the “musealization” of Venice by creating even more of its image as a “tourist park.”

Residents almost have been expelled one might say, by tourists, leaving their homes and turning them into b&b’s. With an amendment to the Special Law for Venice, the mayor for the past year has had the power to limit the overnight stays of tourists but has not yet used this power. Is a less drastic solution being sought?

Let me say: to each his own! It is not up to the bishop to assess the legal and political means by which local governments could deal with the situation. However, I can say that, in spite of everything, there is still a share of the population in Venice that is resident and “alive,” moreover, strongly motivated by their love for this unique city. On the contrary, I believe that the emphasis on the albeit undeniable criticality of the relationship between so-called “overtourism” and residents is, in the end, draining and demotivating. It does not benefit a sick person to nag him with obsessively re-presenting the state of his illness. It only serves to depress him, to persuade him of the irredeemability and inevitability of the situation and, in the end, to make him throw in the towel by eventually emptying Venice of the last residents, some of whom complain that they feel they are regarded as an “inconvenience,” as if they were an impediment to further tourism development rather than the necessary condition for the city to remain alive as a real city and not the backdrop of a stage. This to me seems an indispensable condition for conscious tourism. What enjoyment could a visitor have in being in a city deprived of its very life, of the “living” of its everyday life, of its popular traditions, of meeting and talking in the calli, in the campi and campielli, in the fondamenta, with the people, hearing the characteristic cadence of the dialectal accent resonate? Would he not lose his own experience of visiting?

Unesco would like to blacklist Venice as a world heritage site at risk, blaming it on the overcrowding of tourism with all that goes with it. What do you think of this fragility proclaimed for your city by the world’s top heritage body? Are we really close to the limit?

I hope that this intention should be understood as a willingness to raise the level of guard against a danger that increasingly threatens a unique city in the world, thus emphasizing a risk that in no way should be underestimated. Personally, I understand it as a strong call for a synergistic commitment - in the political, cultural, economic, local, national and international spheres - to better promote the safeguarding and protection of the entire city, its territory and its extraordinary natural, artistic and cultural heritage.

There is much political and administrative debate about solutions to ban or limit tourist rentals. What many Italian historic centers are experiencing is what Venice began to experience first many years ago: the disappearance of stores, artisans and everything that is not useful to a tourist (who is only interested in drinking and eating). Are the churches and monumental beauties that Christianity has produced here over the centuries debased in their value?

I do not agree that a tourist “only cares about drinking and eating.” There is undoubtedly also a superficial tourism and that in traveling seems more caught up in the eagerness to go around in circles, perhaps just for the sake of “having been” to that given place, without actually knowing anything about it. But there are quite a few people who visit Venice because they are attracted by its unique beauty, the extraordinary works of art housed in its churches, palaces, museums and collections, not to mention the charm of a truly unique urban fabric in which those who place themselves in the dimension of observation and listening find a symbolic universe ready to speak to their hearts. The challenge before us today is to overcome the logic of “hit-and-run” tourism, which, to the extent that it is uncontrolled, also becomes a factor in the degradation-even physical degradation-of the city. And the solution is not elitist tourism, but conscious tourism.

The free devotion of the Christian who, in his time, contributed to churches and works of art is contrasted with a city that is very expensive for everyone: residents and tourists (from coffee to sandwiches, from sleeping to transportation). A city where beauty is now only for the rich?

Among the things that are most distressing, especially for large middle- or low-income families, is that so much beauty is not accessible due to ever-increasing costs to precisely those who, perhaps, are more motivated than others and could enjoy it while enriching themselves in spirit and soul. In the qualification of a more sustainable and conscious tourism, it would be desirable to develop some tools to offer more opportunities to those who would aspire to “know” Venice with interest and passion for the treasures of art, history and faith it holds. Art treasures are often the result of the people’s experience of faith. And this should not be forgotten, otherwise they would be “seen” but one would not have the “intelligence.”

What do you think of the mandatory entrance fee required to visit places of worship? Basically a ticket.

The issue is as sensitive as ever. An indispensable condition is that, in any case, free access be guaranteed to those who want to enter the church to pray. In 1997, in order to cope with the management needs and the very high maintenance costs of the churches, the association “Chorus” was also founded, which introduced an economic contribution scheme for access to some churches (not all, today there are 17) that have joined the initiative, with the possibility, precisely, of a unitary economic contribution in the logic of a cultural and theological-catechetical enhancement of the places of worship. This has given the possibility of keeping open many churches that otherwise would have remained closed. But the risk is to lead visitors to consider churches as museum spaces instead of places of celebration. I reiterate that an attempt has been made to remedy this by allowing free access to all for prayer, not only during the times of celebrations, in which the true dimension in which these places are to be experienced is activated, including the works of art themselves that visually illustrate - in authentic pages of theology by images - the mystery celebrated.

What did you think over the years when looking out of your office window you saw the cruise ships, tens of meters high, in this contrast of modern and ancient lapping each other? Are you for or against banning them from entering the lagoon?

The sight of the large cruise ships induced me to reflect on the necessary respect for the delicacy and fragility-almost “sacredness”-of this city and its lagoon ecosystem. It also called to mind the complex demands of work and the lives of many people, in whose inducement they work, and which must also be considered together with those of the protection of a unique natural and urban environment; work contributes to the dignity of the human person. For centuries, the city has stood and thrived on a very delicate balance in which the work of man has interacted with the environment, in a dialogue between man, nature and culture under the banner of respect for the peculiarities of the place and the limits it imposed on human artifice. And man has ingeniously interpreted this relationship to the point of drawing from it over the centuries the elaboration of an urban texture unique in the world: the Venice we know today. Today, we have often misplaced this sense of limit, of harmonious and responsible cooperation with natural reality and available resources; it is what Pope Francis calls “integral ecology,” as an act of responsibility toward human life itself. And we see how our common home, planet earth, suffers. In this respect Venice appears as an iconic microcosm of the relationship with the environment on a planetary scale and can be an interesting laboratory in which to realize a renewed culture of limitation and harmonization because, in fact, the city and the lagoon have been this over the centuries.

Venice is the icon of world art: it has been expressed here and has evolved to the important international manifestations of art, which today is contemporary art. Art with Venice has, therefore, an inseparable union. What has allowed you to have this ability to pass on for centuries this witness of patronage and the pursuit of artistic expression among these islands?

I think it was the extraordinary freedom of imagination and creativity that this natural environment, initially devoid of almost anything, induced in human genius. A creativity fertilized by the experience of interiority, fostered by the quietness of the lagoon environment and the insularity of its civil settlements, from the very beginning, marked by the presence of very ancient churches and coagulated into poles of habitation around them, as was the case, for example, with Altino and Torcello.

What do you think could be decisive in triggering in man that desire for the beautiful and the true that has driven him over the millennia to represent his respect and gratitude to his gods by creating altars and simulacra that were precious and beautiful? Beauty is the splendor of the true one would say....

Beauty is, no doubt, a high expression of the human experience of truth, and the Christian spiritual tradition, reconnecting with Plato and Platonism, describes God himself as supreme Goodness and Beauty. It, however, needs spaces of silence and reflection in order to be grasped and Venice would be the ideal city, in this sense, as the “city of silences” although this property of his is increasingly attacked and eroded by mass tourism and its increasing invasiveness in terms of noise pollution. Here, too, a challenge opens up: in qualifying a conscious tourism we should know how to educate in the contemplation of beauty. In the human sense, first of all, because contemplation is looking and, at the same time, thinking; it is the human in its elementary experience, a condition of the opening of the doors of the heart to transcendence.

When the first people arrived on an island in the lagoon, the first building they cared to pull up was a place of worship. In fact, there are islands that have just the church up to the height of magnificence like St. Mark’s. Today, comparing modern society to that of those early Christians, probably the first thing they would think of building on an island as soon as they docked would be a stadium or a hotel: how much has faith and devotion changed with it and how much has sacred art changed in these centuries?

Despite the materialistic reduction of contemporary man’s experience, our society paradoxically suffers from an excess of “abstraction.” Abstraction from life in its concreteness, first of all, as can be seen from certain attitudes and a certain way of understanding politics and law today and from the position of the individual in civil society; there is like a factory of abstraction that “generates” a right for every desire. Believers themselves, men and women immersed in this time and its culture, suffer from such an inclination in which even faith risks abstraction from life and ends up contracting into an individualistic interiority; it is reduced only to a “thought” that which in reality asks to be “believed” by the whole man-spirit, soul and body (1 Thess 5:23)-. Art, and sacred art in particular, represents a resource of extraordinary value in calling faith back to the Christian realism of the incarnation, putting us back in touch with the beauty of the reality it expresses in its figurative languages. Christian faith at its core has the Incarnation, Passion, Death, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus Christ; it is, moreover, faith in the resurrection of the flesh. Of course, we have to make sure that his works still speak to the human heart and make themselves intelligible in their narratives, which are no longer taken for granted due to the fading of the references of biblical and catechetical culture in many people. Here, too, a challenge opens up to which the Patriarchate of Venice is sensitive.

Christianity has generated a numerically and qualitatively significant heritage over the centuries, and St. Mark’s is of the richest beauty. The message it conveys is that of a people who love their God and offer him the most beautiful gift. The precision of the ceiling mosaics is an example of this. How much do you think art can be a vehicle for evangelization?

St. Mark’s is a unique treasure chest with an unparalleled theological-iconographic concentration. But a church, before recounting a people who love their God and before being a temple elevated by the human imagination - projecting something imaginary out of itself to worship him and pay him human honors -, recounts the experience of a people who, first, were loved by God up to the supreme sacrifice of his Son. And this sacrifice - in the paschal mystery represented in completeness by Christ’s passion, death on the cross and resurrection - draws on the central archway of St. Mark’s the axis that catalyzes the entire history of salvation that unfolds over the entire mosaic surface of the basilica’s vaults and walls. St. Mark’s is the dense and touching narrative of this lived experience unfolding in the history and wonder, generating beauty, of those who have personally experienced what it means to be saved and welcomed into the golden ocean of God’s mercy. St. Mark’s, not for nothing, is called the Basilica of Gold.

Has an artistic vein also disappeared? And is this perhaps a sign of a less living faith? Let me explain: modern churches are often anonymous or, worse, just merely “functional” places to manage an assembly of people, losing sight of the purpose of why we gather. What are your thoughts on this?

Contemporary churches are not always anonymous and insignificant but, unfortunately, quite a few are. Perhaps it can be said that there are more successful and less successful churches. The criterion of judgment must be the specificity of the sacred space for liturgical celebration. A church structured like a conference room, for example, distorts the very understanding of liturgical celebration by risking crushing it on the intellectualistic (if not functional) plane of a catechesis on the readings, when the heart is actually the Eucharist. The success of a sacred architecture depends a great deal on how much it can differentiate itself from the common spaces of everyday life, on how well it can symbolically express “other” and especially “the Other.” The same should apply to liturgical music, which, as the highest form of art, has a very close connection with sacred architecture. In this respect, too, Venice has much to show and tell. In Venice, since before the 14th century, the Marciana Chapel has been inseparable from the Basilica.

In the expression of contemporary artists with religious subjects, even though they themselves are believers, do you not find a lesser ability to be appreciated and effective with the message that sacred art had in other eras?

Contemporary sacred art expresses itself in symbolic canons that are not always easy and immediate to understand, because they are often less expressly iconic, and according to reinterpretations and figurative solutions that, in breaking away from a didactic naturalism in representation (such as had matured, for example, in the late nineteenth century), may be on the aesthetic level more difficult, or less, usable. Mediation and education in understanding the sometimes profound meaning of contemporary sacred art works, especially in the contexts of liturgical space, should therefore be undertaken where possible and sensible.

Often churches and diocesan museums have works that could be better valued in terms of the knowledge of the faithful and also as a source of income, which is always useful in helping those in need. How much does the idea of ’parochial’ doing (in the common negative meaning of the term that stands for something done the easy way) clash with managerial management of works of art?

It clashes at the moment when by ’managerial management’ we mean an entrepreneurial cynicism that, insensitive to the original placement and destination of artworks, would consider them under the sole profile of profit. With respect to this I would opt for “parochial doing,” but expunging from that expression any negative meaning. If there is a place and context in which sacred art can be understood and appreciated in its proper meaning and natural place, making use of it for liturgical life and catechesis, it is that of a living celebrating community. And that is what we call a parish.

Which of the many works of art in the Patriarchate do you most appreciate or to which are you particularly attached?

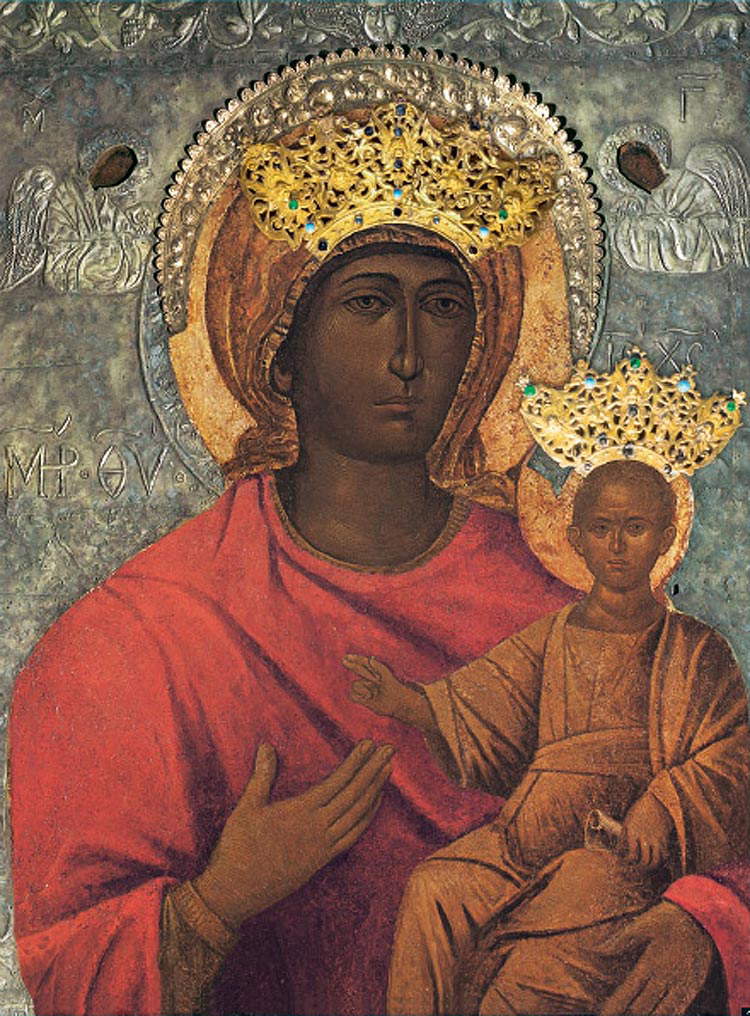

Undoubtedly - and it could not be otherwise - St. Mark’s Basilica, because of the significance of the cathedral as the heart of the diocese and because of the very high concentration of iconography it has. But there are many other places that are densely symbolic for the history of the faith lived in Venice; among them I would point to the Basilica della Salute, beloved by Venetians and still a living testimony of a popular and ignited faith, which comes alive again on the feast of November 21 even in people seemingly far away. If we talk about individual works of art, then I would say the icons of the Nicopeia at St. Mark’s and the Mesopanditissa at the Salute, which have catalyzed popular piety for centuries. And the magnificent Pala d’Oro of the Altar Maggiore in St. Mark’s, a depiction (in a grandiose conception) of the heavenly Jerusalem with Christ Pantocrator in the center between the Evangelists in a feast of enamels, gems and precious stones anticipating the “colors” of the heavenly city.

In Italy, the connection of works of art with Christianity is very strong. In your opinion, has this awareness been lost today?

In Italy, too, we suffer the effects of a deculturation that has produced a kind of religious illiteracy and makes, in practice, works of sacred art unintelligible to many, with the sometimes disheartening effect of finding such inabilities to read even in some insiders, which is unacceptable regardless of the personal faith of individuals. As if a scholar of antiquity could afford to ignore classical mythology, and indeed, in the name of “secularism,” draw boast from it....

In 2025, a year and a half from now, there will be the Jubilee, and here again religious tourism will bring attention from all over the world to our cities so tied to Christian works of art, not including Rome. How is the Venetian Church preparing to introduce lesser-known and touristically very attractive places of faith and to make the frenzy of travel ’with the excuse of plenary indulgence’ into an act of faith lived according to its real Christian roots?

For years there have been initiatives, promoted by the Patriarchate of Venice, for the enhancement and intelligence, among the general public of visitors, of the significance of the works of art in Venetian churches and beyond. One can cite among them the example of the service of guides trained to illustrate St. Mark’s Basilica, which has yielded good results over time, or a column dedicated to the iconological reading of works of art in the diocesan weekly “Gente Veneta.” It will now be a matter of taking up the challenge that in this area comes from the Jubilee, that is, to rethink and channel the many efforts and initiatives to intercept passing visitors more effectively and possibly accompany them, through aids and with studied itineraries, to discover the fascinating labyrinth of the city. The words of John Paul II on his visit to Venice on June 16, 1985, come to mind. In his homily at Mass in St. Mark’s Square he said, “The diocese of Venice has a special missionary vocation. Many dioceses send missionaries to other countries. For Venetians there is another way to live missionary life: it is the world that comes to Venice and visits its churches extraordinarily rich in art. [...] Strong in her Christian identity, welcoming in charity, may your Church always be ready and open to dialogue with cultures, of which Venice is the crossroads, in order to proclaim the Gospel to them.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.