Laura Casalis (Franco Maria Ricci): this is how FMR magazine was reborn.

The historic FMR magazine, founded in 1982, returned to publication in December 2021 after a long period of stop. After the first year of the “new” FMR, we spoke with Laura Casalis, editor-in-chief of the magazine and a work and life companion of the late Franco Maria Ricci, founder of the esteemed publishing initiative, to let her tell us what the new FMR is like and how this first year of new publications went.

FG. First of all, since we are now one year into the publication of the new FMR, I would ask if you are satisfied with the results, if you have met expectations after this first year of publication...

LC. Although it comes naturally, I don’t think it’s wise to make the comparison with what was the first season of FMR: forty years have passed since its launch, and the context was very different; in 1982 the start was fulminating, it came a success beyond the highest expectations because the idea was new, unprecedented. It garnered a throng of enthusiastic comments, which resulted in a veritable harvest of subscriptions. Today, my possible audience has habits and addictions that were unthinkable then, starting with the use they can make of the web’s endless offerings. There has been in this space of time a drastic change in the perception of what is worth seeing in print. To make sense of my FMR, born in the 1920s, one has to be discerning and rigorous in choosing content, first and foremost, but also in choosing the best quality of paper, print and packaging. Wanting to stand out, doing something that swaggeringly proclaims itself for the few by its high price and offered mostly by subscription, are characteristics that exclude the large numbers of the first FMR, but make it an undisputed gift of prestige to give to oneself and others. Am I satisfied with it? Yes, because FMR was liked, readers from back then were happy to find it again, others, from younger generations, who are interested in art, beauty, and things done right, discovered it and fell in love with it. FMR’s audience, then, has much in common with that of the time; it is not, on average, an audience of the very young, although, compared with the FMR of their parents and grandparents, the new magazine is closer to today, precisely from a chronological point of view: in fact, it is interested not only in the artistic phenomena of the distant past but also in those of the past that is much closer and more familiar to us, the art of the second twentieth century and the early two thousand years (unlike Franco Maria Ricci’s magazine in which the twentieth century interested yes or no until the war). I, along with a small staff of intellectuals, who are given to choose themes, subjects and contributions, like to make forays into phenomena that have occurred, shall we say, during the course of my life, thus, albeit in small doses, also in the contemporary. Mostly, however, I try to devote myself, deviating as little as possible from what Franco Maria Ricci did, to lesser-known art, and then to the bizarre, the unexpected, to curious and forgotten phenomena. Let me give you an example: Vittorio Zecchin, everyone knows that he was a very good and very prolific Murano glass designer while few know about his brief past as a painter linked to Deco, to Vienna, to the novelties of the Wiener Verkstätte, with hints of Venetian murrine and Mitteleuropean flavors. Here, what I like is precisely to hunt in these meanderings of art, of things that have remained dormant, around the corner, precisely, forgotten. Formally, as I said, FMR is not much different from its predecessor, everything, however, has become tremendously more expensive (including skyrocketing shipping costs), thus more complicated, not to mention that anyone with curiosities to satiate in the field of art can count on the infinite means that the Web makes available. The Web, a great support for our work, still remains a cumbersome competitor.

It was a bit of a dream of Franco Maria Ricci to restart publications after the making of Labyrinth, but how did you come to revive the magazine? Where did the idea come from?

Franco sold the publishing house when he turned seventy: he had been saying for some time that when he reached that age, in order not to risk that being an editor would become less fun and creative, he would “change jobs,” devoting himself to something completely different, for example, to “creating the world’s largest labyrinth” (which he did and inaugurated in 2015). To do this required time and resources. So he sold the publishing house, looked for what seemed at the time to be the ideal buyer and sold it, still remaining president for a couple of years. Little had changed at first, Ricci continued to set its editorial line, and the staff remained the same. A few years passed, however, and the group to which FMR Spa had been sold had difficulties on other fronts and sold off some of the profitable companies, including FMR Spa...which was acquired by a group with purely commercial business philosophy and priorities. Franco and I, disagreeing with the new management, preferred to sever all relations. The new owners (it was 2002) went their own way making very different products and, interestingly, even trying to hide all “Franco Maria Ricci traces.” Franco watched from afar as they dove into their new projects and, of course, regretted it. Gradually the company lost ground: during the slow decline it was recovered by another company, and then by yet another until the latter went bankrupt. We had begun the process of buying back what was left of FMR when, sadly, in 2020, Franco died. For the last years of his life, Ricci’s dream was to revive the magazine; we had tried, given the impossibility in those years of using his name, to find another one but never came up with one that worked. It wasn’t until a few months after Ricci’s passing that I was able to finalize the recovery of the brand name. Now the magazine could have the same as the name that glorious title that had had tens of thousands of readers for 20 years! Everything suddenly seemed easier and feasible partly because fortunately for me I can still count on long-established collaborations, which are very important to maintain the flavor, grace, and elegance of the golden years. Sources of ideas are everywhere, exhibitions, places, collections, travels; one searches, one inquires, others sail through the real or digital air and one just has to catch them and go deep.

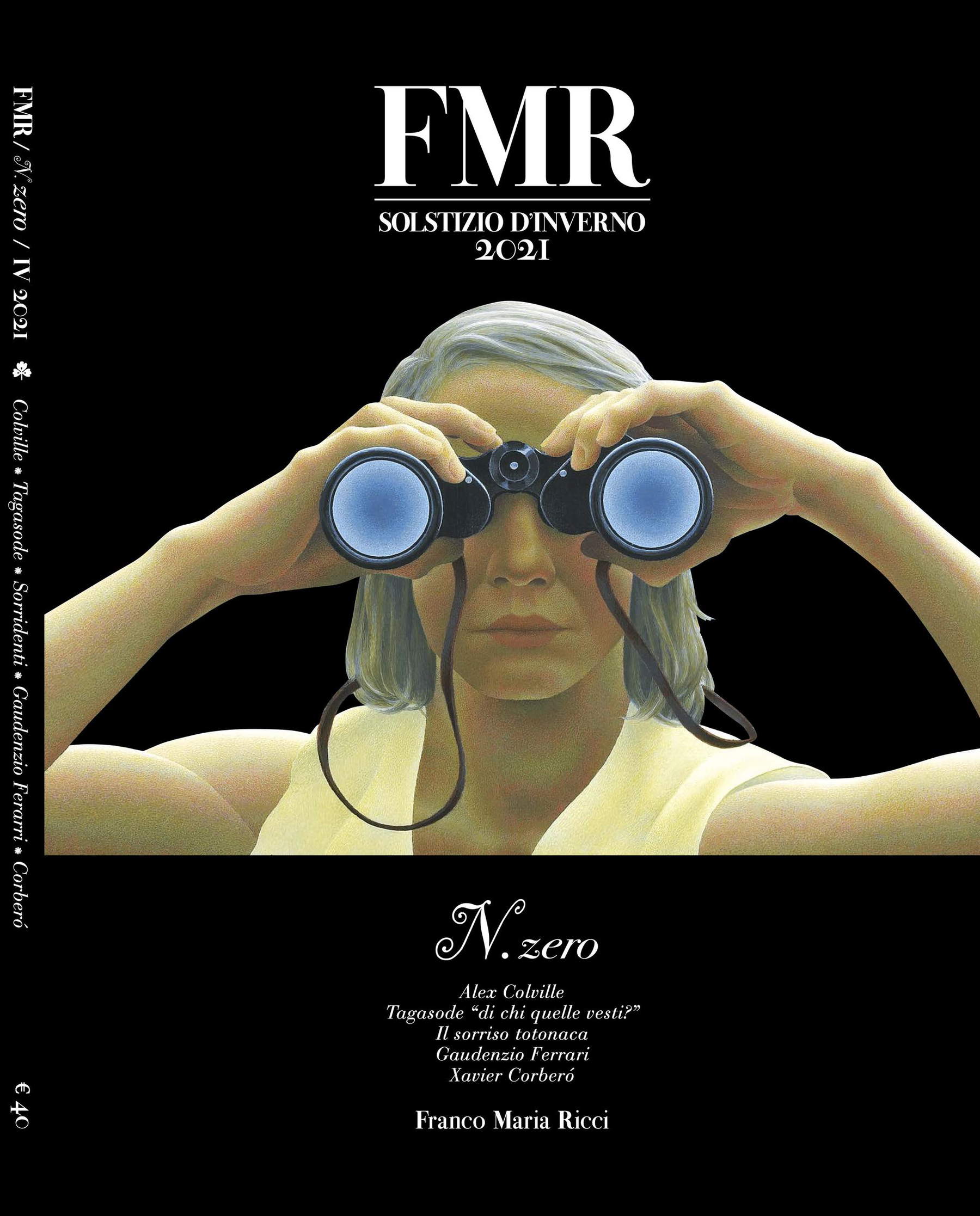

The cover of

The cover of The cover of

The cover ofHere, how do you select topics?

A little bit like we did in the first season. Back then we could count on a much larger staff of contributors than we do now, however, the mechanism of finding ideas for topics and subjects does not change: you read an article, you see an exhibition, who informs you from America who from London, Paris, Madrid, or Latin America. I’ll give you an example: taking a cue from a small exhibition held recently in London on Freud and botany, we felt like tackling this curious subject, lateral, if you will, to Freud’s great and popular painting. Timid suggestions also came from readers; we fluctuate between discoveries and falling in love: that’s the beauty of this profession.

During the presentation of the new FMR it was said that “FMR does not teach art history, but makes people love art by forming taste, the ability to see. It is a school for the eye.” This is a very ambitious goal. How can it be achieved?

This was the project of the first FMR, the main goal of Franco Maria Ricci. FMR came out at a time when other art magazines tended to show small images, often in black and white, interspersed with the text, to privilege rather the face of the curator, or an owner, or the antiquarian. Franco wanted to treat each subject by trying to open doors wide, to show it as a whole and in its parts, getting close to it, revealing every detail. Today we are in a context where art is also being eviscerated by digital media, however, printed paper can still win: taking the reader by the hand to lead him or her to where there is emotion and beauty, and it is through the choice of presentation, that of privileged details, that the eye is educated. And then, offering along with the seduction of the images that of the text, printed on pages of beautiful paper in crisp Bodonian typefaces.

You said earlier that so much of the audience is the one that was already fond of the historic FMR. But if you were to indicate the target audience, the typical reader, what kind of person is the one who reads FMR? What is your target audience?

Many among FMR fans are mature-aged adults who are happy that FMR is back, because they remember when they were high school or college students and made sacrifices to buy it. So, partly an audience who loved FMR when they were young. The “new ones” are people who like art, affluent, who have time and space at home (magazines, to be collected like ours ask for space in the library). That is why ours is an audience with a more advanced average age than that of many other magazines. They are professionals, entrepreneurs; there is a very cross-sectional audience; it is difficult to categorize it. It knows how to appreciate the dreamy thread of suggestions and the passion for refinement; here, FMR is a set of themes represented by beautiful images and refined texts, which coexist in each issue in harmony with each other.

It is, however, an audience that still seeks quality....

They look for it and have the tools to appreciate it. It doesn’t happen for large numbers...

Instead, what differences are there from the historical magazine?

The new FMR ventures into art-historical eras close to today by hosting art phenomena of our time, more so than the first one, which was led by Ricci, who did not have a great passion for the contemporary. His was a very personal magazine: he imagined it page by page, checked everything, nothing escaped him. Franco Maria Ricci was a true craftsman, he never put his hand on a keyboard, even though he lived with the age of computers, he did everything by hand, he would point out the cuts of the photos on the light table, one at a time, then delegating to us graphic designers and the editorial staff to carry on the work until it was printed. Craftsman yes, but with great entrepreneurial skills. He was a magnetic man able to coalesce around him the complicity of many when he wanted to. For example, the campaign he did to launch FMR in America was crazy. On his own, he found gigantic sponsorships, calling together “made in Italy” entrepreneurs with interests in the US. A masterpiece, a stroke of true marketing genius.

When you worked together, how did you divide the work?

The editorial staff at one time included about 20 people divided between those who were in charge of texts and those who were in charge of images. My job was to superintend the image coté, so I worked with the photographers, the photolithographers and the printer; I would send forward the visual part following Ricci’s directions, not after discussing them, however, even animatedly, with him. The written part in the hands of another group of people who worked with those who provided the textual contributions, art historians and writers, and they would add those short texts that introduce each article (and which are the ones that everyone reads) and, of course, invent the titles. For language editions, we came to have editorial offices in Paris, Barcelona, London and New York. Their work then flowed to Milan for layout and printing.

To conclude, going back to what was said at the beginning about the web actually introducing a revolution compared to when the historic magazine came out, in a society where the internet has brought the upheavals we all know about, but especially where communication is now faster and faster (we see it on social media), how do you talk about art to the public?

By looking for “goodies!” As I said, nothing obvious or already overdone, never overly technical or geeky articles, and the first five issues published say I am succeeding. I want the articles to always favor storytelling to fascinate even a less knowledgeable audience, to inform without boring, to fall into the world of entertainment. With enticing themes, with beautiful signatures: formidable ingredients, to be blended with grace and wisdom.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.