La Contesa on Picasso: Rachele Ferrario tells the story of Fernanda Wittgens and Palma Bucarelli

There are essays that read like novels because they deal with facts, characters and issues that arouse interest and curiosity even in a lay audience. Credit is due to the writer, who is skillful in leading the reader to discover the protagonists of such stories, making them alive and relevant within the subject matter. In The Contention over Picasso (ed. La Tartaruga, 2024), Rachele Ferrario recounts with passion, simplicity of style and narrative clarity the parallel stories of Fernanda Wittgens (Milan, 1903 - 1957) and Palma Bucarelli (Rome, 1910 - 1998) who competed in setting up the first exhibition that Italy would dedicate to Pablo Picasso: two exceptional women who changed the history of Italian art, reinventing the very idea of the museum and anticipating some current trends. The first as director of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Brera, in Milan; the second, directing the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome and as a stalwart promoter of Italian artists after World War II. Twentieth-century specialist, teacher of Phenomenology of the Arts at the Brera Academy in Milan (but also curator of exhibitions, archivist and essayist) Rachele Ferrario is busy these days promoting for Italy this short essay, which evokes a perhaps little-known but undoubtedly compelling page of our recent cultural history. A history that culminates in 1953 with the double Picasso exhibition, first in Rome and then in Milan.

FL. How did the idea for the book come about?

RF. The idea was born while writing the biography of Palma Bucarelli. I had been left with the exciting story of the challenge for the primacy of the Picasso exhibition between Rome and Milan. After writing about Palma and Margherita Sarfatti, a third important female figure was missing, that of Fernanda Wittgens, active on the Milanese scene. In this book, I tell the story of two very different women who compete for the setting up of the first Picasso exhibition in Italy; in the background, many secondary characters and the historical events of two great cities that, at the dawn of the post-World War II period, are reborn, open to artistic (and other) novelties and compete for cultural supremacy in Italy.

What is the substantial, and most obvious, difference between the personalities of Fernanda Wittgens and that of Palma Bucarelli?

Both inherit the lesson of Margherita Sarfatti, who is the first true art critic in Europe. For a time, at least until 1945, their lives seem to run parallel: they are avowedly anti-fascists; they are used to dealing with power and politicians; they both do their best and risk their lives to save art masterpieces from the destruction of war. As soon as the conflict ceases, however, everything changes. For the next twelve years, Wittgens and Bucarelli mark each other closely: they admire each other but experience a kind of antagonism, determined to make the museums they refound and direct great: the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan and the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. Wittgens has an anti-modernist outlook: she is an art purist. Bucarelli, on the other hand, is modern or, rather, modernist and looks primarily at the contemporary. The contention for the Picasso exhibition is the meeting-point-clash between these substantial differences. The challenge between Fernanda and Palma is also on the level of communication: both appear in the magazines of the time and exploit the language of the popular press to show women that it is possible to have a social, and even political, role outside the home.

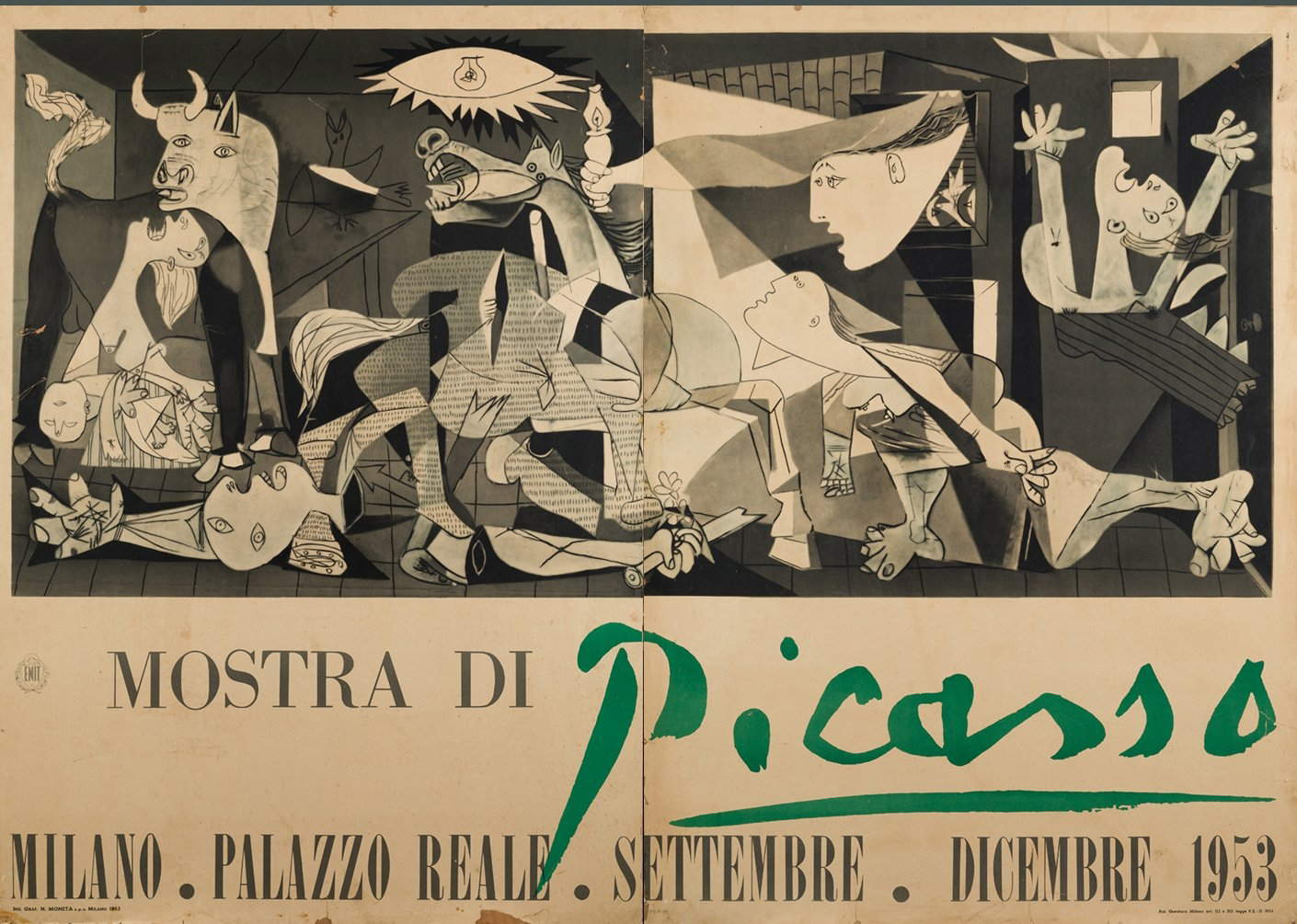

1953 is Picasso’s year in Italy. His presence (not personal, but of his works) marks a fundamental moment in the artistic growth of reborn Italy. How do the exhibitions in Rome and Milan differ, critically and in terms of exhibition design?

1953 is the symbolic year of Italy’s cultural rebirth. In Rome, Bucarelli makes the first major critical exhibition in Italy dedicated to the work of Pablo Picasso, focusing particularly on the last period of the artist’s production. However, the Roman exhibition is penalized by the upcoming political elections. The canvas Massacre in Korea has arrived in the capital, but a letter to Palma Bucarelli from Christian Democrat undersecretary Giulio Andreotti prevents its exhibition. Wittgens at the Palazzo Reale, on the other hand, will manage in September to put together an exhibition with works also by the early Picasso and, above all, to present in extremis, and almost at the close, the large canvas by Guernica, the symbol of the tragedy of the war that is displayed in the bombed hall of the Caryatids. If in Rome politics plays against Bucarelli, in Milan the same politics (with the victory of the DCs in the then recent elections) favors the choices of Wittgens and Milan itself, a city symbolic of the Resistance.

Is dealing with culture today still a political and social act as Fernanda Wittengs and Palma Bucarelli understood it? In what does their modernity consist?

Some time ago, on social media, Marina Abramovic quoted Matisse who, during the war, painted only flowers. Neither, after all, did Picasso during the two wars go to the front or fight in person, even though he was in fact a “political” artist. All art, as such, acts on human ethics and cannot but have a political role, in the high sense of civic responsibility. For Wittgens and Bucarelli, it was obvious that personal behavior was reflected in political action, commitment and social ethics: it represented their vision of their world. For both, in fact, the civic sense of protecting the artistic heritage coincided with the defense of the dignity and memory of the human being. An ancient concept of the highest civilization.

What is the role of a museum or art collection today, public or private?

Today museums can increasingly become places for reflection and social gathering, as well as custodians of historical culture and artistic memory. They have extraordinary communicative potential and can become narrative displays, that is, places where stories are told and the possibility of a new utopia is conveyed, within the great dystopian box in which technological man is enclosing himself.

Upcoming dates for the presentation of the book La contesa su Picasso by Rachele Ferrario

April 2 - Venice, Venice Biennale, Ca’ Giustinian

May 8 - Casale Monferrato, Accademia Filarmonica

May 10 - Verona, Museo degli Affreschi

May 15-19 - Turin, Salone del Libro (date to be determined)

May 28 - Lecce, Biscozzi Foundation

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.