Jake Chapman: The audience for art? I don't like to talk about that. You pick the beauty you like

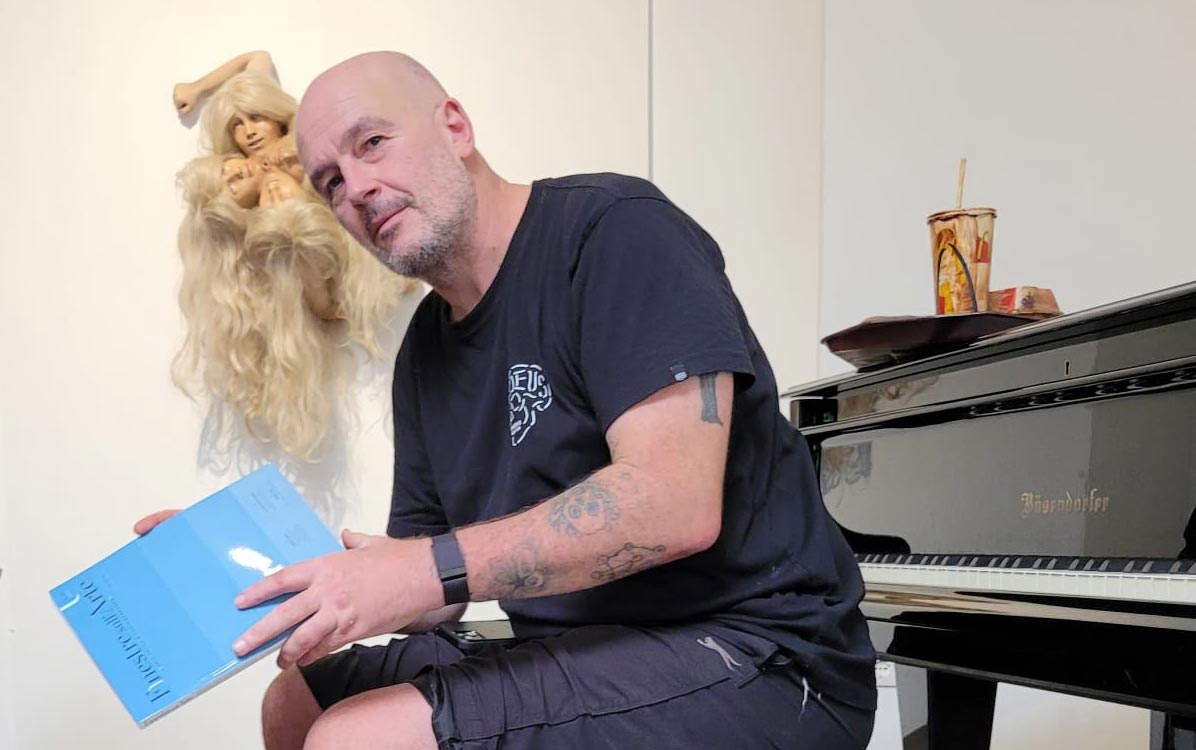

From Aug. 11 to Nov. 5, The Project Space gallery in Pietrasanta hosts the exhibition “The Blind Leading the Dead” by Jake & Dinos Chapman: protagonists of the latest revolution in European art, the Chapman brothers represent the most provocative and transgressive wing of yBa (young British art), an aesthetic and media phenomenon that exploded in London in the early 1990s. For Jake & Dinos Chapman this solo exhibition, staged by The Project Space gallery team with texts by Luca Beatrice and Alessandro Romanini, marks their return to Italy after an absence of about fifteen years. We interviewed Jake Chapman who gave us some of his thoughts on contemporary art: here is what he told us. Interview by Federico Giannini.

FG. Let’s start with the exhibition: why was this title, The Blind leading the dead, chosen? And what should the public expect from the exhibition?

JC. The title of the exhibition comes from the saying “the blind leading the blind,” which an expression that stands for the hopelessness of people who have no hope who in turn lead other people who have no hope. And I thought it would be more interesting if it referred to the procession of the damned as people who have died--but in the end it’s just a title. What should visitors expect? To leave excited. Or even a little bit amused.

Among the works you are presenting in Pietrasanta is a very recent one, Monument to Immortality: how did this work come about? And why did you choose to present the series as a “monument”? Monuments today are a much discussed topic....

Monumentsto Immortality is a series of exploding belts copied from exploding belts that did not explode. They are works made of bronze, and bronze is usually the material used to commemorate heroes, i.e., the kind of sculptures of soldiers, generals and so on that you see kind of scattered all over the cities. As for their significance, we were only interested in making a work that would be a monument to the moment when someone’s claim to immortality occurs....

The public is often shocked by the works you present -- but usually what kind of reactions do you register?

I can’t really think of a general reaction to our work. I mean, it depends. Some people have a strong sense of morality and find our work very difficult, and some people have a sense of humor and find it funny ... so obviously the reaction to the work varies infinitely, but I think it’s possible that our work leads the audience to have some kind of relationship with its critical function. Then there are those who see the humorous side of the work, those who see its sinister side, some are offended...in short, the reactions are varied and many. It is difficult to know, and I certainly do not want to be the arbiter of others’ interpretations regarding the work. This is the work done and finished, and once it is finished it becomes the audience’s problem. Or at least that is the part, I think, that by contract is up to the audience.

Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman,

By the way, you have often stated that once the work leaves the studio, it is no longer under the control of the artist. What does that mean? Does the artist really not have the slightest control over the audience today, or can he or she somehow predict how they will behave and then draw counterclaims as he or she works on his or her work?

I’m not really sure what the audience is. Who is the audience? Is it a kind of official bourgeois elite? Or is it a kind of liberal elite? Or is it a general audience composed of people who are not very familiar with art? In short, I don’t really like to talk about the audience, who the audience is. It is rather difficult to know-I find it more interesting to know that the idea that the work is no longer part of me once it leaves the studio comes from the fact that, in a sense, the artwork is only an approximation of the artist’s intentions. I think it is also possible to consider a history of art that also excludes the people who created it. There is no correlation between the artist’s intentions and the work of art. That relationship is entirely tentative and not self-evident. It is impossible to own the meaning of a work of art. If anything, the reason making art is interesting is because it dismisses the artist. The artist is the least important element in the process. Once the artwork is somehow finished, then it no longer has any responsibility to uphold the artist’s intentions. In fact, as mentioned, I think you can imagine a history of art that excludes the artist, and it would probably be a more interesting description of the process of making art.

So what do you think an artwork is for nowadays? Is a work of art still capable of disrupting or subverting according to your point of view?

I think this idea that art can shock or subvert, or at any rate in general the idea that art occupies a kind of countercultural position within society ... is vaguely sentimental. I actually think that counterculture is now the status quo-I mean, counterculture died in 1968, or so I imagine, and as far as whether a work of art has a kind of critical success, I think that if anything that comes from its ability to affect people. I think art functions as an instrument that draws people into a kind of melodramatic pantomime in which they participate. And their own reaction is a kind of melodramatic reaction. If people assume that somehow a work of art should be shocking, then I think they play their part in the exchange by pretending to be shocked. Because, in the end, I think anyone who is shocked by art is probably also shocked by... I don’t know, by zucchini.

And speaking of critical functions, it is often said that art criticism is dead today. What is your relationship to criticism? What do you think the role of art criticism should be?

Again, it’s very difficult not to think that art is becoming a kind of arm of bourgeois gentrification, so it’s very difficult to see art criticism as having any kind of purpose other than expanding markets, not to see it as a kind of a performative vehicle of capital, and so any kind of countercultural ambition cannot not be tied to the fact that even when we use counterculture to express, let’s say, our anti-capitalism, we are actually still participating in capitalism. So let us consider that even the most abject works, or those that enact or offset our sense of revolutionary spirit, are still participating in the capitalist system. I am deeply pessimistic about the possibility of art functioning critically, because I see criticism as part of a kind of capitalist dialectical movement.

You have often said that you do not think that art is to be linked to the idea of progress. Instead, we often tend to think the opposite, that art should look forward, and that an artist, in order to show talent, must necessarily be original, do something new. So do you think it is possible to be simultaneously current and anti-progressive?

I’m not sure I said I was anti-progressivist, but at any rate if one questions progress without assuming that it is the natural impetus of any form of activity, whether science or art or whatever, one’s notion of progress implies that there is an ultimate goal for progress. You cannot have infinite progress, progress implies that there is some kind of civilizing process. However, when we talk about progress we usually talk about ideology. We talk about ideas like those of the Enlightenment. And enlightenment is an ideology. It is not a natural order of things, and so we need to perhaps rethink what we think is natural. “Progress” is a term. So what is natural about progress? There is nothing natural about progress, just as there is nothing natural about the humanistic assumption that progress is something good. There might be an enlightened idea that can direct us toward an industrial form of genocide, for example. Because you can safely reconcile the notion of mass genocide, for example, the Holocaust, with Enlightenment principles. They are absolutely, completely the same. So progress does not necessarily mean progress toward something that is in some way evolutionary, toward some positive direction.

Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Jake and Dinos Chapman,

Jake and Dinos Chapman,

If we have to rethink what we think is natural, then what could be defined as “natural”?

I actually don’t think the word “natural” is a useful term. I don’t even think it can be an optimal background for discussing anything. I think the concept of nature itself is a very prejudicial term, and I think it is very difficult to define what nature really is. Either everything is nature, or nothing is nature. And if everything is nature, if nature includes everything, then it also includes what is supposedly against nature, like atomic bombs, pollution--there is nothing unnatural about pollution. There is nothing unnatural about climate change. There is nothing unnatural about humanity’s acceleration toward its own extinction. These things are all absolutely natural, and once you argue for nature, why should you then resist nature? Because if you resist nature then you make it unnatural. And it is unnatural to resist extinction.

Let’s go back to talking about the exhibition. This is your first solo exhibition in Italy after many years of absence. Why did you come back?

That’s a question I can’t answer. I mean, unless there is some kind of Italian conspiracy not to invite us, maybe then this is the first exhibition since the conspiracy started. Really, I don’t know. It could be the pope! Take it up with the pope. It’s all his fault.

One last question (which also partly has to do with the pope). Here in Italy art is often associated with the concept of “beauty,” especially in political rhetoric. Your art, on the other hand, seems to me to go in the opposite direction. What do you think beauty is?

Whether you are discussing taste or sensibility or some kind of human proportion of beauty, or whether you are discussing some kind of Kantian notion of beauty, which is a bit like an understanding (or even a lack of understanding) of the greatness of matter and all those things that compel you toward the concept of death (the sense of the sublime and so on), so beauty can be a kind of overwhelming sense of impending death, or it can simply be a beautiful color. You choose whatever beauty you like.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.