Isao Sugiyama. Forty years in Italy, seeking dialogue between man and nature. The interview

Born in Shizuoka, Japan, in 1954, Isao Sugiyama is an artist who has lived and worked in Carrara, Italy, since 1983. His path began with figurative art and then came to Shrines, the series that has characterized his work since 1989 and which Sugiyama has never abandoned . An artist highly appreciated by the market, present in several editions of the most prestigious fairs (from Art Basel to Art Brussels, from Arte Fiera to FIAC in Paris), with his Shrines he has experimented with a language that proposes to Western audiences different elements of the Japanese way of looking at nature. In this interview by Federico Giannini, we looked back at the career of Isao Sugiyama, who will be returning to Japan in a few days after spending nearly forty years in Italy, and delved into his language.

FG. How did your passion for art come about and how did you decide to become an artist when you were still in Japan?

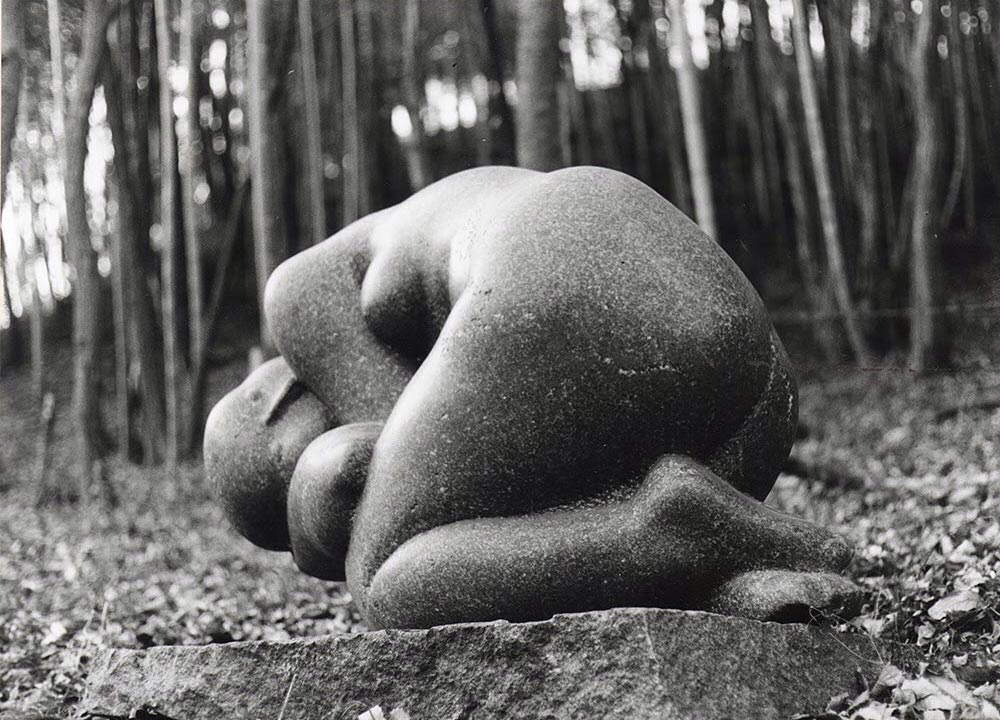

IS. I wanted to become an architect when I was studying in high school. I took courses then in mathematics, physics and similar subjects-I planned to pursue that career. However, the last year of high school I changed my mind: the fact was that few architects in Japan at that time were able to make it to the top, and it would have been difficult for me, following that career, to express myself at my best. I decided then to devote myself to sculpture to be more free. Before I entered Tokyo-Zokei University of Fine Arts and studied sculpture, I studied art history and was fascinated by a sculpture by Picasso, She-Goat: I felt that it was much more realistic than what naturalist art had produced. However, I cannot explain why: it seemed very real to me, though, and so I decided that sculpture would become my art form. And then I was more interested in the third dimension than the two-dimensionality of painting. In college every day I modeled with clay, even from life, and I did this for four years. Then, in my senior year, I started sculpting granite, always staying on a figurative style. After graduation I took a graduate course, and the last year I attended a symposium in Tokyo: that’s when one of my professors advised me to go to Italy, because he thought it would be useful for me to look at another world. At that time I was already working: I had been a truck driver and I was teaching, I was earning enough, and so I didn’t want to go to Italy, I wasn’t interested in going abroad.

What, on the other hand, spurred you then to follow your professor’s advice?

My professor had ... pushed hard to send me to Italy. Then two people I knew had been to Carrara and I had listened to their experience. I then decided to move there and enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara. It was a total change in my life .

What did you think you would find in Carrara?

In the meantime, I wanted to change my way of working: I had never sculpted marble, I had only worked on granite, so it was a totally new experience. At first it was not easy, and I’m really talking about the relationship with Carrara. I had no money, I wasn’t rich, I wasn’t even handsome, and I found it difficult to settle in. Then as soon as I arrived in Carrara I was robbed, and also swindled: I had rented a fund, and with the owner we had agreed to make him the contract for electricity and him the one for water, because in the fund there was still nothing. I made the contract right away and started paying, but he didn’t do anything for his share for more than two months, and I was really angry about that. Then fortunately some residents helped me, and that story ended. I then found another workshop, but it was full of water infiltration, when it rained it always flooded. I worked together with the owner of the fund, who was a roughneck, and he only spoke in the Carrara dialect, then he was swearing all the time. Every day he would talk to his mother on the phone and ask her to pick him up after the work was done: the first phrases I learned in Italian were one in dialect that he said to his mother every day (“O ma’, ven’m a piar’,” meaning “Mama come and get me”), and then the profanity. He was a very good person though, nice, kind, who also taught me how to use the tools to work marble. Later then I found a third workshop, definitely more comfortable. In the meantime I continued to attend the Academy, but let’s say I was spending about 70 percent of my time in the workshop. At that time I was still doing fine art, because marble was a new subject for me anyway.

Isao

Isao

Was it difficult to learn to work on marble?

Yes, I was used to using a black granite from Japan, which is a very strong material that has a strong resistance. Marble, on the other hand, is softer and has a completely different look. It was difficult for what I wanted to express, my works at that time also conveyed a very strong idea. With marble, however, I was able to change my style, I made my works less angular, working more on the planes. In order to change my figurative style I studied modern Italian masters: I studied the works of Marino Marini, Pericle Fazzini, Emilio Greco, Giacomo Manzù, artists of the new Italian figurative art that I had already seen in Japan. Seeing everything live was a big shock, because before in Japan I was looking more at French art, like Rodin and Maillol, and in the Italian art of the time I found more freedom, and then I found it more innovative. That was also a reason for my moving to Italy. I was disappointed that I could not meet any of them in person, because some of them had recently died when I moved to Italy, and Manzù, who was the only one still working, I could not meet, although my professor in Carrara was in contact with him. Then I happened to be in a period when (I arrived in Italy in 1983) the art of the moment was transavantgarde, there was no art magazine that didn’t talk about it: however, I preferred to look also at Arte Povera, which would later have a certain impact on my style. I really liked, for example, Giuseppe Penone (and still do!): I was impressed by his way of hollowing out the logs, leaving only the shell. So I feel very close to the poverists, also to Mario Merz, for example.

What, on the other hand, is your relationship with ancient art?

When I was at the Academy I used to go around a lot to see ancient art. It must be said that I was always a bad student (I was more interested in practice than theory) so in Japan I had never been more interested in Italian art. However, when I arrived in Italy I started to study Italian art history (in Japanese books, because I understood little Italian). I went around then to many museums, to see all art, from Greek and Roman to Renaissance, modern to contemporary. I toured for several weeks: Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan... but after seeing the works of the great masters of the past I felt enormous discouragement, I thought they could not be overcome. I had come to the point where I thought they had already said it all and so I felt no need to add my figurative art.

Was this then the reason that led you to completely change language by abandoning figurative?

No, actually at that time I didn’t want to change language-I really wanted to quit! I felt disappointed, demoralized. For some time I was still, I wanted to go back to Japan, defeated. But before going back to Japan I also wanted to see the French museums: I had never been to the Louvre and the Pompidou, they were two museums I wanted to see. Before I left then I took a trip to Paris, and I devoted the whole first day to the Louvre. I couldn’t tear myself away from the Mona Lisa, I stood thirty minutes in front of her, close, from half a meter away, because at that time one could approach it more freely than now. That visit accentuated that sense of defeat I felt, because I was impressed by that work. Then the next day I went to the Pompidou, and seeing the abstract and non-figurative works I changed my mind: at that time I was obsessed with finding new avenues in the figurative, and I had not considered expressing myself in a different language. I wondered if I could then do something more personal, if I could look for another way to express my feeling and ideas. I then went back to Carrara and started to try many other things, and I took a year to experiment with marble. So at a certain point I started another path.

Isao

Isao Isao

Isao

Isao

Isao

How did your art change then afterwards?

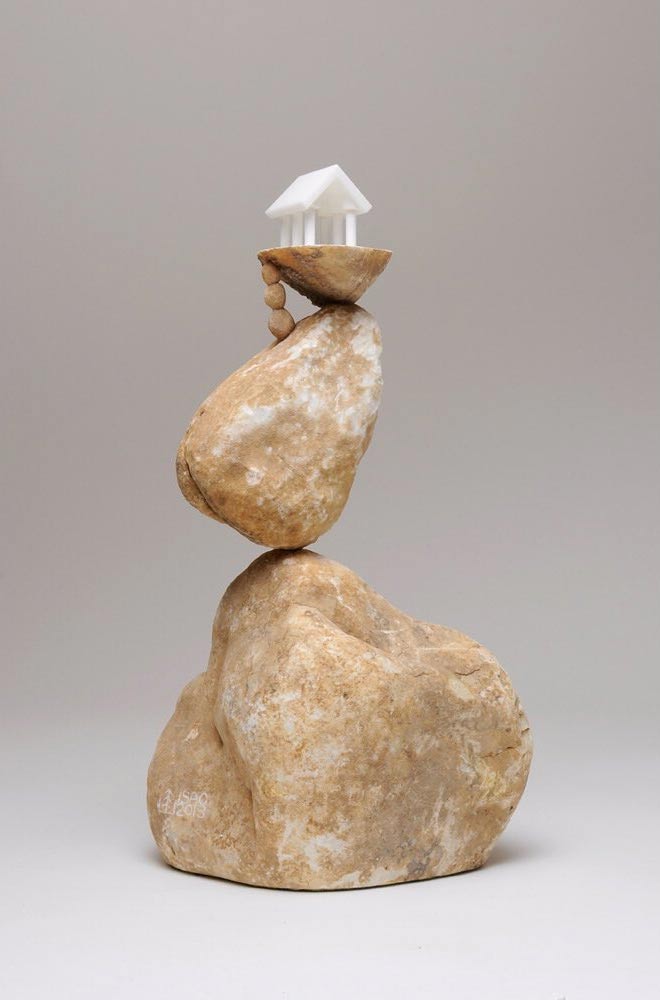

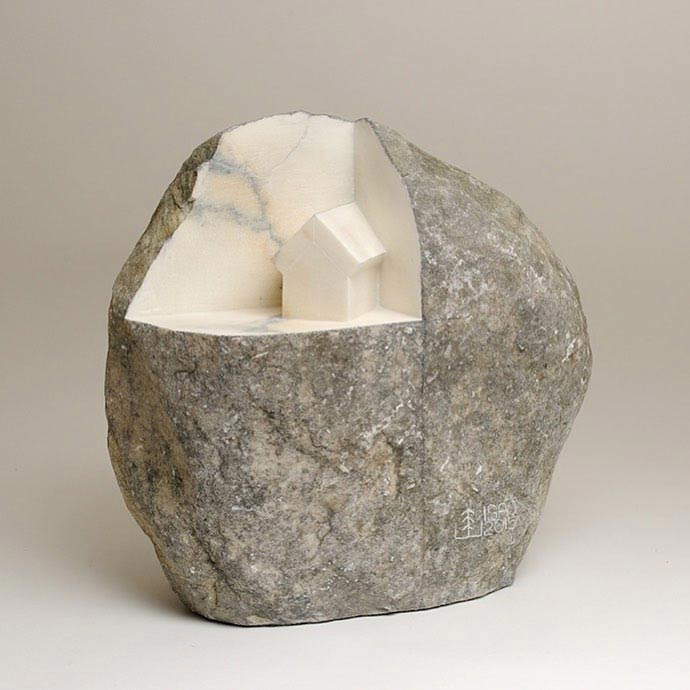

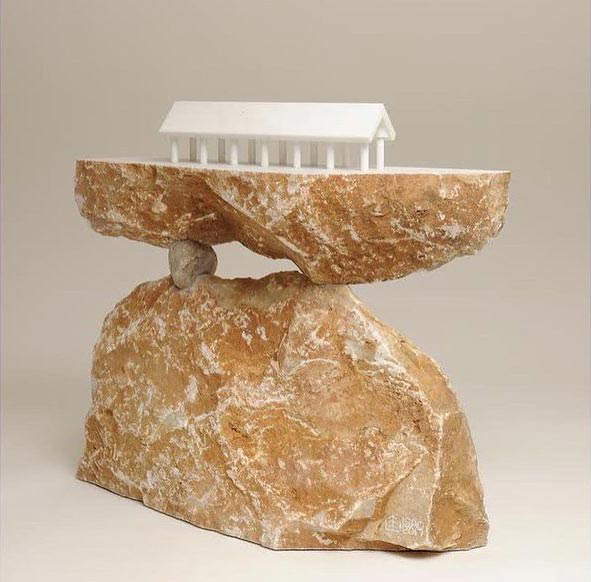

I became interested in postmodern languages. I used to think that you Westerners have centuries of history to look at, but for us Japanese it is more difficult: after the Meiji Revolution [1866-1869, ed.] art also began to be “imported” from abroad. The very concept of “art” in Japan was born a hundred and fifty years ago. In our culture there was no concept of “art” similar to that in the West before, so I had to look for a reference point in our history, thinking about what I had studied in Japan. Also, I thought I had to go back to what I liked as a child-I was passionate about modeling, and this passion inspired me for the framework of my new art (I like to think of my art as consisting of a framework). So I created my first new work by hooking a wooden frame to marble-I had thought of it simply by looking at a window. I felt like I had created a shrine: thus began the Shrines series, which I still work on today.

How did Arte Povera affect theShrines, if at all?

It certainly had an impact, but it is difficult for me to explain. It is essentially a matter of materiality-I find Arte Povera to be very material. Before, when I was doing figurative, for me art was essentially a matter of form and meaning, and I neglected the material a little too much. Arte Povera made me change my mind about this aspect; the material is now fundamental for me. The material speaks: a wooden structure speaks, a piece of marble speaks. Also for this reason I have chosen to work often leaving the forms natural (to create the shrines I carefully choose pieces of marble directly at the quarries and on those I then build the shrines): it is a dialogue between nature and structure. Another theme then is that of time: marble is a mineral, wood is vegetable, and as time passes, the wood part rots and disappears, while the marble remains. When the wood disappears, a marble with a hole in it remains: it is the sign of the passage of time. I thought about this when I first visited Rome and its archaeological remains: archaeology, in this sense, also appealed to me and inspired me.

Why do you leave the forms natural when creating the Shrines?

In Japan we have a great respect for nature. When we construct a building or a temple we make sure that the intervention in nature is as minimal as possible. If there is a stone in the place where something is to be built, we don’t remove the stone: we go around it, or we build on top of it, but without altering it, and if we have to, the intervention will be minimal. The idea is that once the architecture is gone, the natural element should be seen exactly as it was before it was built. After arriving in Italy, I felt very much the difference with the West: Westerners mostly try to conquer nature, and have, if anything, second thoughts afterwards. Orientals, on the other hand, ask nature first. According to the Japanese religion, Shintoism, there is a god for every element of nature (a tree, a mountain, the moon, everything has its own deity), and every time you build you have to ask permission from the deity: you do a ceremony, you make offerings to the gods, you pray, and this puts us in a strong relationship with nature.

And after starting the shrines , the success also started.

Yes, the work literally took off, I wanted to work continuously on this project, I had many ideas. I started doing the first exhibitions: the first one at the Naviglio Gallery in Milan, in 1989. There were three rooms in their premises: they granted me one, and in the other two, at the same time, there was an important master of figurative art. Initially I felt a little discouragement because I only managed to sell three pieces, while the other artist instead managed to sell 80 percent of what he brought to the show, and I thought there would be no other possibilities for me, I thought I had no future. However, I asked the gallery director, Renato Cardazzo, if I could continue to collaborate with him, and somewhat unexpectedly he said yes: “you produce so many shrines,” he told me. So I set to work, and after some time he proposed that I take my works to Art Basel. I didn’t know that it was such a big fair and such an important fair: the gallery proposed me to the fair committee and they accepted me, so I had the opportunity to have a solo show at the Naviglio booth , even managing to sell 70 percent of the works. After that occasion, which was a success, I received so many requests: there were 30 or 40 galleries that wanted to represent me, and I accepted some offers, for example the one from Galerie Claude Bernard in Paris. And then a lot of collectors became interested in my work: so I was able to enter the art world also from the economic point of view, which was a different thing than I imagined, because I thought that the artistic aspect was completely detached from the economic one. But actually the truth is that if you don’t sell you can’t produce. In my case I was lucky, because I entered the world of collecting, which allowed me to continue my work all my life.

Isao

Isao Isao

Isao Isao

Isao Isao

Isao

Are there people you met during your journey in Italy that you remember with particular pleasure?

Yes, there are several. I would start with Ottavio and Rosita Missoni. I met Rosita at the Bologna fair: she bought one of my sculptures as a birthday present for Ottavio Missoni. After the Bologna fair, at a solo exhibition of mine in Milan, I met her on Ottavio’s birthday itself, and after the party many guests came to the gallery to see my work, after they had seen the gift. Some later became my collectors. Then I have very good memories of Fausta Squatriti, who was my professor at the Carrara Academy: she gave me many suggestions, and it was thanks to her that I came to Milan. I often went to her even after classes because the topics she explained were difficult for me and I wanted to go deeper. In one of these meetings she asked me if I had ever shown my works in an exhibition. I answered no, because I was not represented by any gallery, I did not know any gallerists. She introduced me to some galleries at that time: the first one that represented me was Studio 111 in Milan, which was run by Vittoria Marinetti, daughter of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and then the second one was Naviglio. I also have very good memories of Renato Cardazzo, who was then director of the Naviglio; he had great charisma. I remember a particular episode related to Studio 111: Vittoria Marinetti as soon as she saw my works asked me to take three of them to Milan immediately, and I managed to sell them immediately. With Naviglio, on the other hand, success was not so immediate. I did manage to come close to the Venice Biennale, though: in 1990 the Biennale also had a section for artists under 35, it was called Aperto ’90. Cardazzo knew one of the curators, and he presented my work to him, proposing it for the Biennale, which the curator liked. It was 1989, Aperto ’90 was being prepared: I had just turned 35, but when the Biennial would start, I would be 36 ... so I couldn’t participate. It was then that Naviglio, perhaps also to mitigate some of the disappointment, offered me the first solo show. Finally, two critics and journalists: Giorgio Soavi and Sebastiano Grasso, who wrote the first texts for my works. With their writings, they got so many people interested in my work and came to see my works at exhibitions. So I also owe it to them that so many at that time liked my work.

Let’s close with a perhaps difficult question: what is art for you?

When I was young I would have answered in many different ways. Now, however, I say that, in my opinion, art is a desire. When you design something, when you imagine the effects that it can arouse, when you create something and see what you thought realized, you feel a strong emotion, which I could not describe, but which for me is stronger strong than emotions you feel for example when you eat or make love, which are also these desires, but art is a more exciting desire, because for an artist the effect is much stronger. It’s like an ecstasy. And so I will continue to design and make also to try to experience these moments of ecstasy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.