"Irony is survival, in art as in life." Conversation with Chiara Lecca

Chiara Lecca (Modigliana, 1977) graduated in 2005 in painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna and in 2008 took part in the Fondazione Spinola Banna per l’Arte residencies in Turin. She focuses her research on the relationship between man and nature to bring out the fracture operated by contemporary society. The animal element, in particular, becomes matter for a process of semiotic alteration. He lives and works in Modigliana.

His solo exhibitions have been held in several public and private museums including Museo Bagatti Valsecchi in Milan in 2024, Collezioni Comunali D’Arte in Bologna for Art City Polis 2017 and in the same year Museo Carlo Zauli in Faenza, Fondazione Ghisla Art Collection in Locarno, Switzerland in 2016, Naturkundemuseum Ottoneum in Kassel, Germany in 2015, MAR Museo d’Arte della Città in Ravenna in 2010. He has exhibited his works in numerous public museums and private galleries in Italy and Europe including the MAN Museum in Nuoro in 2024, Galleria Fumagalli in Milan in 2023, Monitor Gallery Pereto AQ in 2021, Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium in Norway in 2018, Schloss Ambras Innsbruck in Austria, Museum Schloss Moyland in Germany and Castle Gaasbeek in Belgium in 2016, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Gallerie d’Italia and Villa Necchi Campiglio in Milan in 2013, the MIC in Faenza in 2015, 2013 and 2012, Spazio Thetis in Venice in 2011, and Kunst Meran/o Arte in 2009. In 2019 she was invited to the MACRO Asilo project room at the MACRO Museum in Rome and in 2016 she exhibited at Palazzo Reale Milan with the work Dark Still Life as a finalist in the 17th Cairo Prize. Her work has been presented in various Italian and European institutions such as the Italian Cultural Institute in Madrid in 2018 and Kassel County on the occasion of the 2012 European Art Camp EUARCA.

His works are present in public and private collections such as, among others, Kassel County Palace (Germany), Naturkundemuseum Ottoneum, Kassel (Germany), Mus.t Museo Settore Territorio (Faenza), Ghisla Art Collection Foundation (Switzerland), Kunst Meran/o Arte (Merano). Since 2008 he has collaborated with Galleria Fumagalli Milan, the year of his solo exhibition at the Bergamo location. In 2020 he founded the Clarulecis Collective. In this conversation with Gabriele Landi, he tells us about his art.

GL. It is often the case that an artist’s work is rooted in the mythical age of childhood: is this also the case for you?

CL: I confirm that it is so for me too, I think that the period of childhood can be considered the only time frame in which we face the world with an atavistic gaze, where all the parameters given by the society in which we will spend the rest of our lives are not yet formed. I would define the age of childhood as that of great fears and great wonders. These are the reasons why I find it so fascinating, not only as an artist but as a person. I spent my childhood in the Romagna Apennines, on my family’s farm - where I still live - and I retain invaluable memories of that period. Such as savoring the sense of freedom, of discovery: I used to spend whole days exploring the territories and creating new adventures together with my brother and cousins, around us there were no gates or fences so the feeling was that we could reach any place we could imagine. Smells also were an important factor, from the most sublime to the nauseous, all of which have remained in my memory. Then there was - and still is - the herd: I was therefore interacting at the same time with the animal and plant world, as well as with the human world. Dealing with animals, all aspects related to the birth, caregiving and death of living beings punctuated my days. I can consider these dynamics as a legacy left to me by my paternal family-for several generations devoted to pastoralism-where the cycles of life are linked to those of nature. All these aspects I believe have contributed to my imagery today.

Did you have an artistic “first love”?

I don’t remember a real first artistic love, however, I do remember a vignette in a summer homework book from elementary school where we were asked to draw what we wanted to do when we grew up, and I filled it with a large bouquet of flowers.

At the time you were drawing you were painting.... ? When and how did you get in touch with the expression of your creativity?

As a child I drew really a lot, partly because I was good at it, plus I loved to assemble materials I found inside and outside the house: I would build a little bit of everything, from the most absurd collages, to small objects to rocambolic architecture in which I could hide. My mother studied at the Art Institute for Ceramics in Faenza so the creative world was also a common thread in my childhood. I then developed a more defined language during the years of the Academy of Fine Arts that I attended in Bologna. In fact, the first experiments with organic materials date back to that period, born during classes in Artistic Anatomy and Painting, because I felt the need to speak of the reality I knew best, in direct line with the world in which I grew up. We all come into the world with starting points that we cannot ignore. At that time I still did not know how to store organic materials so I used to store my small assemblages in the freezer at home and transport them as needed with a small cooler.

What did these assemblages look like?

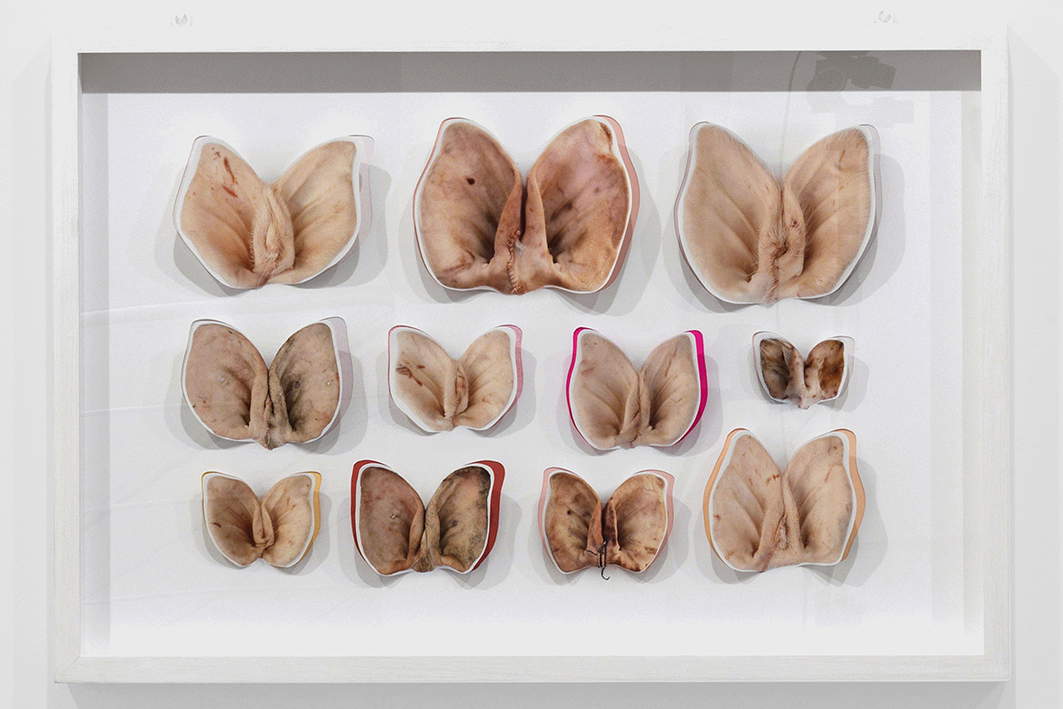

I mainly assembled organic parts of animal origin to objects of use, in truth not far from what I do to this day, but at the time I was definitely more irreverent. One of my earliest works consisted of a polka-dot hairband on which I had sewn pig ears, all enclosed in a blister pack in the style of a commercial object, it was 2003 and the work is titled “Pocket Ears”

During your formative years were there any encounters that left their mark?

My mother and her poetics. And definitely my Art Anatomy teacher who supported and encouraged my early experiments with organic materials. An important meeting was then with Annamaria Maggi, who in 2006 took a gamble on a perfect stranger fresh out of the Academy and welcomed me among the artists of her gallery: the Fumagalli. At the time based in Bergamo, now in Milan. Our collaboration continues to this day. And because I think the formative years never end, I add the encounter in 2014 with Jannis Kounellis and his thought, so powerful and extreme.

Does the alchemical aspect ever matter in what you do? I am reminded of the Prince of San Severo and his experiments on the transformation of organic matter....

In truth it has never mattered much, I am a rather practical person, the processes I use on organic matter are mainly a means and hardly an end. Certainly, however, characters like Raimondo di Sangro are very interesting, as are the ancient wunderkammer and all their imaginative power. Probably in what I do the aspect related to the transformation of matter is more important, as may be the aspect related to the preservation of food over time.

I would like to ask you to talk more extensively about your idea of time and the idea of transformation.

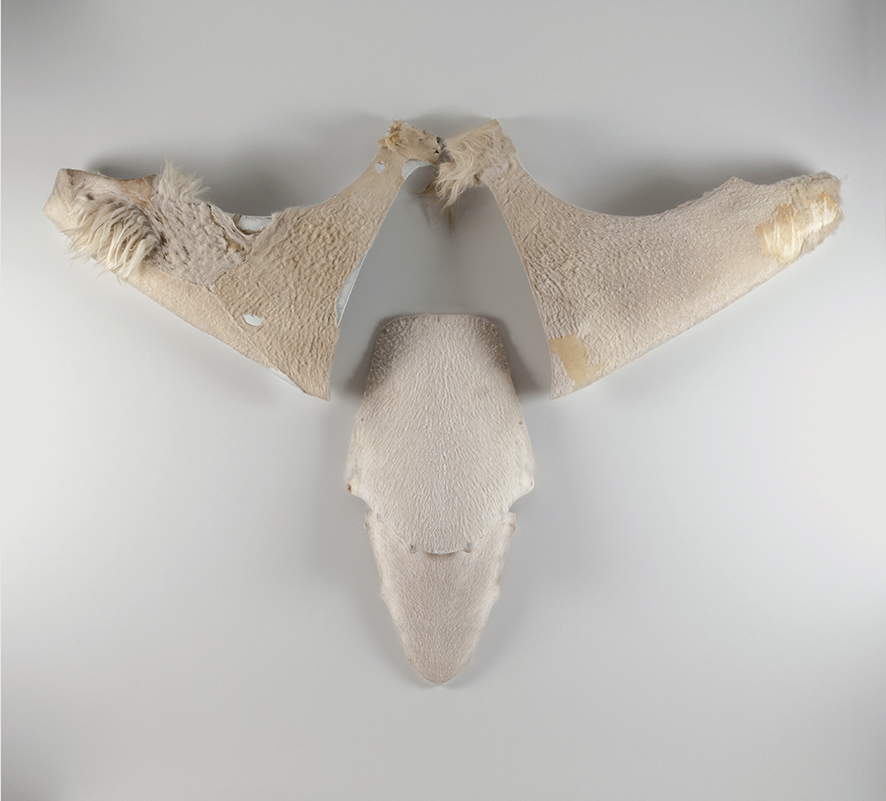

Instinct guides me toward materials but time causes them to be transformed into language. In fact, time is a determining factor in my research that needs dilated time frames. The work Lapped Rocks (2017) is emblematic in this respect: it is composed of mineral feed blocks stacked to form a small architecture. This type of feed is taken up by cattle in the barn to tap into the supply of mineral salts. The pivotal element is the stasis time of the blocks with the animal, and my role was to ponder this time as the animal involuntarily shaped their shape by licking them. I find that the long process of making a work is as important as the end result because it serves to scan the impulses that gave it life. And this is directly reflected in the reading of the finished work, which needs multiple looks, multiple levels of reflection, extended time. Actually, my priority is not that the work can be read immediately, rather I am interested in creating a state of tension. This leads the viewer to keep it with them even after the viewing experience, involves questions and provokes a desire for deeper reflection.

Does the idea of staging matter in what you do?

What interests me is to translate inner fragilities into something real, physical. These are feelings that are difficult to summarize in words, while the material makes them concrete and above all shareable. It is therefore a way of translating reality. I am reminded of Kounellis and his desire to translate reality in the most extreme way. That is why the idea of staging certainly matters and is the consequence of an intimate and personal process, it is the last scene of an inner dialogue that was born much earlier. I can describe it as an attempt to restore tragedies - understood as the unresolved points of our living - on a stage dictated by the society in which we live. And those who enjoy it complete the work.

Can you talk more broadly about the relationship between your work and the audience that comes to see it?

The artist with his work can only reach a certain point, it is as if he is building a bridge in the middle, the other part is up to those who come in contact with the work, in this way a relationship is built. With art you throw out worlds that belong to you but that in some way can be akin to those of the viewer: the magic happens the moment the viewer finds his or her own personal connection with these worlds.

What is your idea of nature?

Nature is part of us, we ourselves are organic nature but we are so distracted or self-centered that we tend to forget that. I often try with my research to investigate this aspect. I try to look at our evolutionary past, which is rooted in the natural world, whose archetypes are projected down to us in the present time, and in the same way, to our society in its becoming. Nature is definitely a source of inspiration for all my work. I find anthropocentrism suffocating, when compared to the breadth of the earth and the living beings that inhabit it.

In your work, what role does the short circuit between attraction and repulsion play?

It certainly plays a primary role: what repels us? What attracts us? Is it possible to have these two feelings at the same time? I think so, and when this happens, our certainties are cracked and it can create junctures for discussion. I remember that during the exhibition A fior di pelle at the Collezioni Comunali of Palazzo d’Accursio in Bologna in 2017, the audience was strongly attracted to the large bouquets of flowers, the Still Lives. They were attractive because they were set up in keeping with the space’s baroque furnishings. But upon closer inspection, the attention switched to the process and materials of making them: this feeling of attraction and repulsion was very evident. I care a lot about the formal aspect because the harmonic form attracts us and puts us at ease, this aspect can become the pass to open a reflection. We also see this in nature: often the most attractive living things are also the most fearsome.

Does the imaginative dimension also tie in with a narrative aspect?

I would say yes, the narrative aspect is important. Like a novel in perpetual evolution to which a new piece is added for each chapter. You get a sense of the content by flowing through the narrative. My whole research can be seen as a continuous narrative that has been going on for several years.

Is there also an ironic side to what you do?

Let’s say that an ironic undertone accompanies me from the beginning. In some works it is latent, in others overt, but by and large it is always present. It is a way to trigger the narrative, or, like a catapult, I use it to get to an unexpected point of view, it is definitely useful to talk about uncomfortable aspects. Irony then is survival, in art as in life.

What importance do the titles of works have for you?

They often add to the reading of the work, sometimes they make it even more cryptic, and at other times, they are indispensable for proper understanding. I give a lot of importance to titles; they are also part of the work.

Is drawing a practice that you frequent? What importance and role does it play in what you do?

As I mentioned, as a child I used to draw a lot, these days I frequent it less but it is still important because it is necessary at the time when I have to fix new ideas or new projects. By drawing something you can fix its details on paper and in your mind at the same time.

Is there a spiritual tension in your work?

There is tension related to the creation and transformation of matter. Matter understood as carrying an intrinsic energy. Any successful work then possesses its own autonomous and new aura, where the law applies that the whole is greater than the sum of its individual elements.

What is your idea of death and how do you relate to it?

Death is a complex concept; it is a theme that has fascinated and frightened humanity for centuries. It is an inevitable event, but its understanding varies widely across cultures, religions and personal experiences. Certainly it is part of everyone’s life, the most difficult thing to conceive of it lies precisely in the fact that we can only narrate it as spectators and not as protagonists. The death - and birth - of living beings are components of my experience and a legacy of my past. In my work I stage death no more and no less than it itself is present in contemporary society, the difference lies in how I “tell” it. How to relate to it is a question I ask myself first and foremost, and that is why I feel the need to make it a part of the work.

Where do you stand in relation to your work?

The moment a work is truly accomplished it becomes other than me and is capable of its own autonomous life, I step out of its aura. If it is born as the custodian of my frailties, once it is concluded it can become the custodian of everyone’s frailties.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.