Born in Paularo, in the province of Udine, in 1945, Julius Candussio is internationally recognized for his mastery of mosaic art. His training began at the prestigious Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli in Spilimbergo, an institute that has promoted the study and experimentation of mosaic since 1922. After completing his studies, Candussio returned there in 1994 as a lecturer and, since 2004, took on the role of artistic director, contributing significantly to renewal and research in the field of contemporary mosaic. Candussio’s career is characterized by constant experimentation with materials and techniques, which has led him to explore the expressive potential of mosaic in relation to architecture, urban spaces and new technologies. A pioneer in the application of computer graphics to mosaic, he has been able to fuse tradition and innovation, expanding the pixel- tessera equation and giving his works a unique chromatic sonority. In this interview, Vera Belikova delves into Julius Candussio’s artistic journey, exploring his sources of inspiration, the innovative techniques he developed, and his vision on the evolution of mosaic in contemporary art.

VB. Why did you choose mosaic as your expressive language and profession?

GC. When I was very young I lived near Aquileia and often visited its archaeological site. The large mosaic surfaces had excited and attracted me so strongly that I expressed to my mother my desire to become a mosaicist. A strong conviction had matured in me that mosaic was congenial to me, and that the practice of this craft would allow me not only to earn a living, but also to grow as an artist and as a man. I think I was precocious in those years in recognizing the artistic quality of the mosaics I admired and what my path would be. I had sensed that those mosaics contained an important lesson for me, one that would mark my long journey as an artist by showing me the way to mosaic. In truth, a mosaic is not seen with the eye, but learned with all the forces of the spirit, attuned in that particular form of theirs called “the lyrical intuition” or “the aesthetic image”: I understood that the mosaic had to exist only for itself. My professional history testifies to the stubborn and almost maniacal search I conducted for long years, and to my continuous if fertile dissatisfaction (I was told by the way, that this which is a typical datum of authentic personalities: the restlessness of wanting to touch the extreme of one’s possibilities). Mosaic was very important to me, it constituted the highest aspiration and at the same time the greatest effort in an attempt to achieve those goals I had set for myself when I was young: to contribute in a tangible way to improving the image of mosaic, its technical and aesthetic quality. I think making mosaic takes three things: the hand, the eye, the heart, I think that’s a very fair observation: two things are not enough.

For what reasons does your concept of mosaic differ from that of “traditional” mosaicists? What does it mean to “think ”in mosaic’ and what are the rules of mosaic language?

Many believe (often rightly), that mosaic is nothing more than applied art subservient to painting. The limiting judgment excludes mosaic from what are true artistic expressions by relegating it, in fact, to a secondary role. This depends on the quality of the mosaic, which in turn depends on the work of “traditional” mosaicists, who are primarily concerned with reproducing, or worse, copying as faithfully as possible the pictorial models and mosaic cartoons. “Traditionalities” conditioned by customs imposed by market rules, in a social context where mosaic has an important economic value. It becomes inevitable to clash with different lines of thought, between different expressive methods, especially if they come from cultural contexts outside the boundaries of “traditionality” and outside European borders. Mosaic, beyond the many possible readings, and beyond its fascinating affair, is an extremely concrete form of artistic expression endowed with its own internal rules, its own linguistic statutes (which we often forget about); it is not a trivial attempt to translate a mosaic cartoon or a pictorial model: it is instead the result of an encounter in which the initial project is annulled and the artist’s style merges into the language of the tiles to design a new discourse. The mosaic is ultimately the result of an encounter, a total welding between the architect, the artist (the author of the mosaic project), and the mosaicist. The architect, in his project, has already envisaged the use of the mosaic knowing well its limitations and potential, has chosen the place where to place it considering the effects of light filtering between the tiles. The author of the “painted” project shows us in the cartoon how he designed in function of the mosaic, making its syntax, compositional, institutional and technical rules well evident. The mosaicist knows the strength of the sign and knows that the outline is a very important element in defining the color fields, delineating those boundaries that the tiles will occupy with the force of light and color. Fundamental will turn out to be the mosaicist’s knowledge of color construction that starts from the original “Theory of Color” expressed in Greek, Roman, and Byzantine mosaics. With this linguistic heritage the mosaicist’s thought gesture will be prepared, which he will recreate, without betraying the initial project, being able to express something truly his own, of his personality: one could say of his soul.

How can one explain the attraction of mosaic to people? Can one recognize the true values of mosaic without proper preparation? Why do so many amateur mosaic enthusiasts today try their hand at creating the most disparate and improbable decorative formulas possible?

Mosaic is a crucible where matter, light, color and space come together in subtle balance. With tesserae, one is able to build a system and a relationship between the one and the whole, where the individual unit contributes to the whole. Mosaic awakens desire, in the object and of the object: this desire is color, light, music of rhythms and scans, refined tactility in which, at the moment of realization, the craftsman’s hand is totally present. Mosaic therefore plays a fundamental role in what is the process of transforming the functional object conceived with a character of industrial design and realization, returning a bodily emotion, a decorative splendor, a perceptual intensity, which moves it away from simple and banal functionality, bringing it back to the glow and splendor of its mythical dimension. Thus the purpose, not least, of re-valuing artistic and craft techniques as an expression of the Genius Loci, that is, of the history, memory, imagery and material culture of the area, was also realized. Mosaic in its most authentic form of expression is, on an aesthetic level, a dry and strong result, precisely because of its formal and chromatic essentiality. It fascinates us through the magic of the light that makes the mosaic surface vibrate, and through the sinuous movement of the tesserae that move at regular or irregular gaits, at twists and turns, at sudden ignitions that produce a magical surface of light and shadow that is made vibratile by the flow of light reflected from one tessera to another. In the mosaic, the colors become brighter, the lightings more vivid, the contours more fragmented, yet at the same time more solidly paced. Light is the subject of the mosaic, and by an analogical and symbolic way it produces asceticism and the dimension of the sacred, the swirling and rhythmic moments of matter are enclosed in the paradigm of a mosaic representation, and therefore, more than exemplifying, they are eternal. Mosaic has its own compositional, institutional and technical rules that, should constitute an irreplaceable wealth of knowledge, for the benefit of all those who want to approach the world of mosaic. Knowledge is an indispensable tool that helps us understand and judge things for what they really are. I have been fortunate to know, since childhood, that value I call aesthetics, that is, the ability to recognize art with our eyes. I believe that society or the masses can only appreciate art if they have attained a certain level of education. This idea reinforces my belief that art cannot be received automatically, but that to understand it, one must deal with it at length or study it. I am convinced that aesthetics is a human aspiration and that this term should return to enrich our experiences of life and culture. Contemporary man needs to rediscover the perceptual and fantastic life, is increasingly alienated from an unrestrainedly technological, artificial and polluted civilization, and engages in improving the spaces of our living by making works of “public art.” They have the primary purpose of beautifying the most prestigious spaces in our cities and, at the same time, actually demonstrating the foresight of administrators and politicians. But the work of art before us sometimes disorients us: we are looking at it with attentive eyes, and without any prejudice, and we realize that there is no empathy and no communication between the work of art and those who are looking at it. Vulgarity becomes more and more present and spreads victoriously without anything and anyone stopping it or attempting to do so. No one risks it anymore, no one takes a clear stand, no one has the courage to speak the truth for fear of losing out. The artist, the critic, the gallerist have become less demanding in comparing their own work and the work of others, attracted by the rush to emerge and make money, but the fact is that the artist is encircled by a sick art system, in an arbitrary and tyrannical environment, and while trying to make their voice and role heard, they do not always rebel against the attempt to be turned into a link in the complex machine that moves the world. Of how much the word culture and the word art is used and abused today is sadly well known. But the times are what they are. I try to summarize in a line (unfortunately not mine), “When the sun of culture is low, dwarfs look like giants.”

In 2013 he wrote and published the Manifesto “BEING MOSAIC” signed by leading Architects, Designers, Artists from various disciplines. How did this document come about, what impact has it had on the mosaic world? What are the highlights of this document and why did you feel the need to propose them in this formula?

“BEING MOSAIC” was at that time, and still is, an intentionally provocative manifesto: At the origin of the manifesto is a reflection on the current state of the entire international compartomusivo and the misunderstandings still alive about the nature of the mosaic language, which have heavy repercussions in terms of the market: mosaic is considered too expensive a product compared to its aesthetic value; as a result, the profession of mosaicist has become increasingly devalued and today enjoys, even in economic terms, very little consideration. It is therefore necessary to shed light on what mosaic is, how different it is from painting and sculpture. We need to understand its limits and know its expressive potential, we need to know how to “think” in mosaic, that is, to apply from the design stage that formal and chromatic simplification that is an intrinsic characteristic of this technique. This also means thinking about it in an architectural dimension and implies the welding of architect, artist and mosaicist. Only by working together will they be able to understand both the potential and the limitations of the mosaic language. Only in this way, thanks to this synergistic effort, will the finished mosaic become something that remains in time, that has the strength of great creations and can therefore also be upgraded from a productive point of view.

What role has the Mosaic School played in your life? What is the role this school should play in relation to other schools, mosaicists, and the entire mosaic industry?

I was a student of the Friuli Mosaic School in the four-year period from 1958 to 1962. Before that time I had built up a particular view of the nature of mosaic by assiduously attending the archaeological site of Aquilea. There I discovered mosaic and, at the same time, learned “the great Aquileian lesson,” an authentic founding pillar on which my convictions rested: the realization that mosaic was nothing more than the expressive language of a completely autonomous art. At that time in history, in the entire mosaic universe and school environment there were very different lines of thought from this one: artisan operating traditions that started from far away consequent on the line of thought of Domenico Ghirlandaio who called mosaic “painting for eternity.” Thus a reproductive technique enslaved completely to painting. A distorted mosaic, deprived of its linguistic distinctiveness, reduced to mere applied art. During the period in which I was a student at the Mosaic School, the teaching staff of the school consisted mostly of artisans/teachers: the best ones, those who had been chosen to teach, had been trained during a long apprenticeship in the workshop, which had been followed by a practice of the trade exercised in the most disparate places in the world. They were the repositories of all the secrets of the trade, secrets that in some cases they themselves had “stolen with their eyes” from old artisans jealous of their knowledge: ideal teachers to pass on knowledge and craft to the students of a vocational school, and at the same time, give continuity to the “tradition” in which they believed. My unchanged beliefs helped me to overcome the currents of thought of my teachers, to whom I never reproached anything, knowing that they had given me all they could give me. I drew a lot from their technical background, and from their behavior I learned a love of work, dedication and professional ethics, which is no small thing. In 1994 I was called by the Management of the Mosaic School to make my contribution to a major renovation of the school’s teaching, which was no longer in step with the times. My tenure lasted twelve years and I served as teacher and artistic director and was able to fulfill a promise I had made to myself when I was still a young student: if I ever had the chance, I would be for my students, the teacher I had not had. In these twelve years devoted almost entirely to the school I believe I have given the best of myself. I have had notoriety and attention in return, but above all else, I have had the gratitude of my students, which has totally gratified me.

Your artistic path is not only related to mosaic, but to painting, sculpture, drawing, and computer graphics: how is it possible to go from one expressive language to another and still remain recognizable?

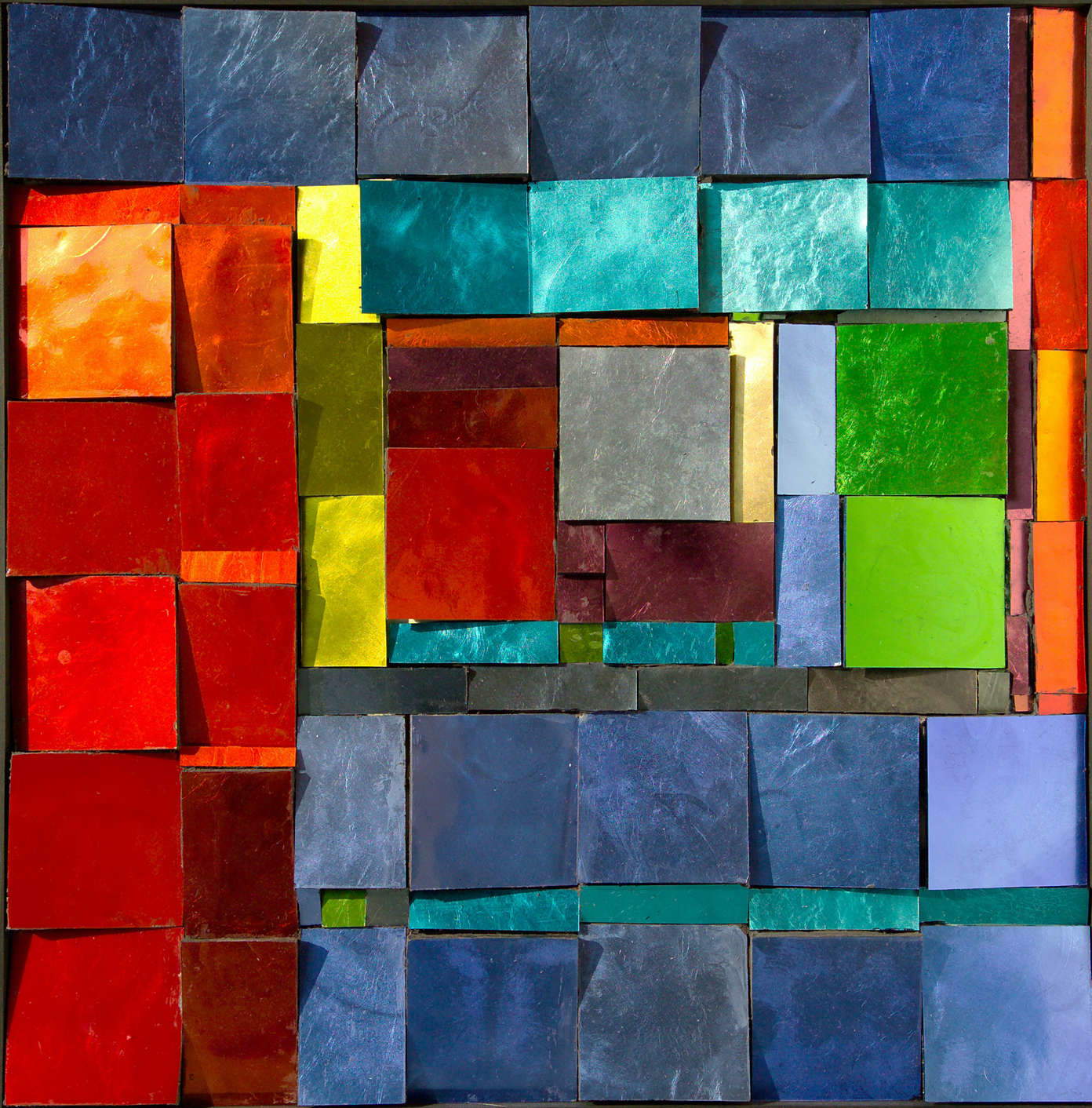

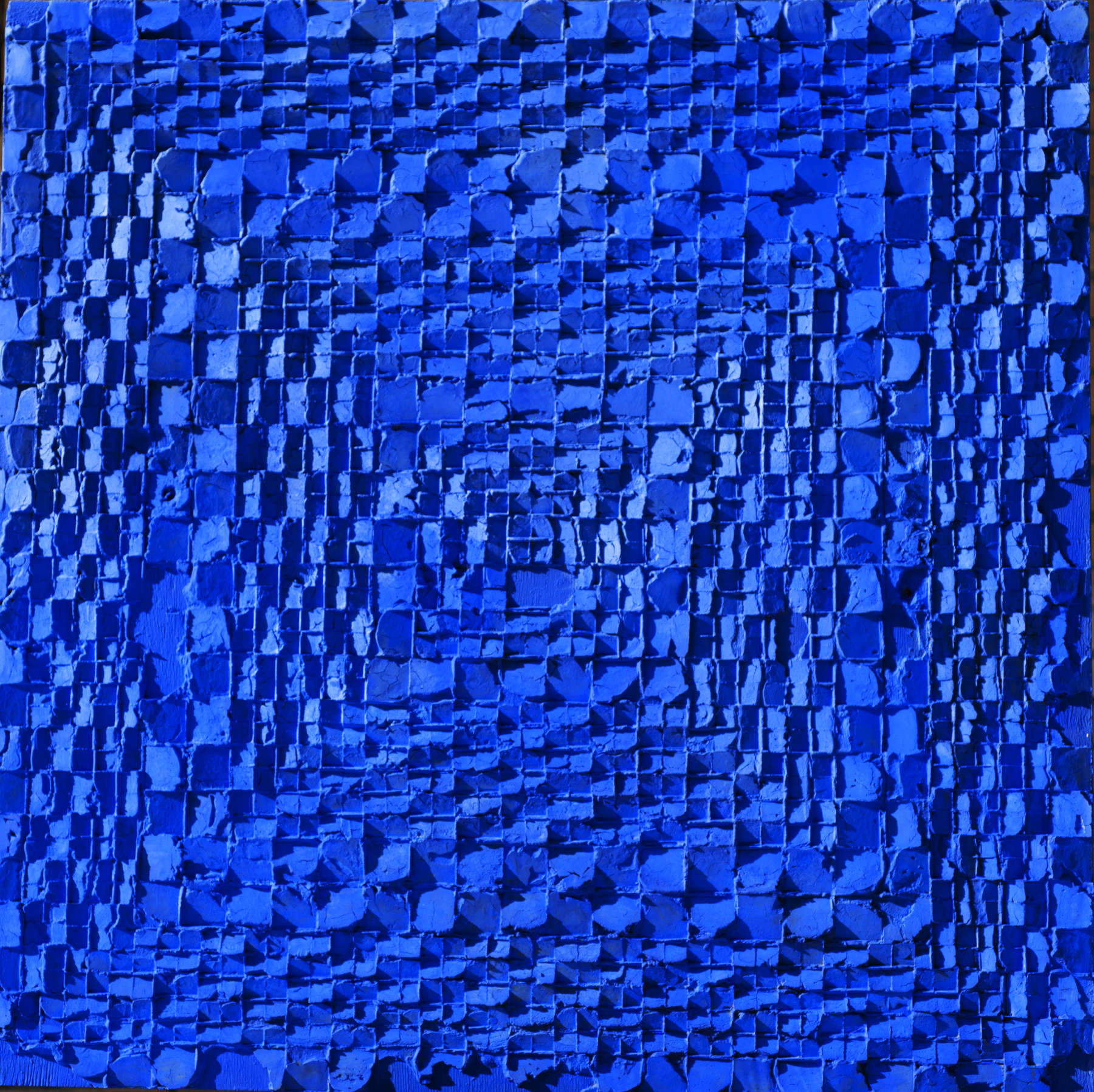

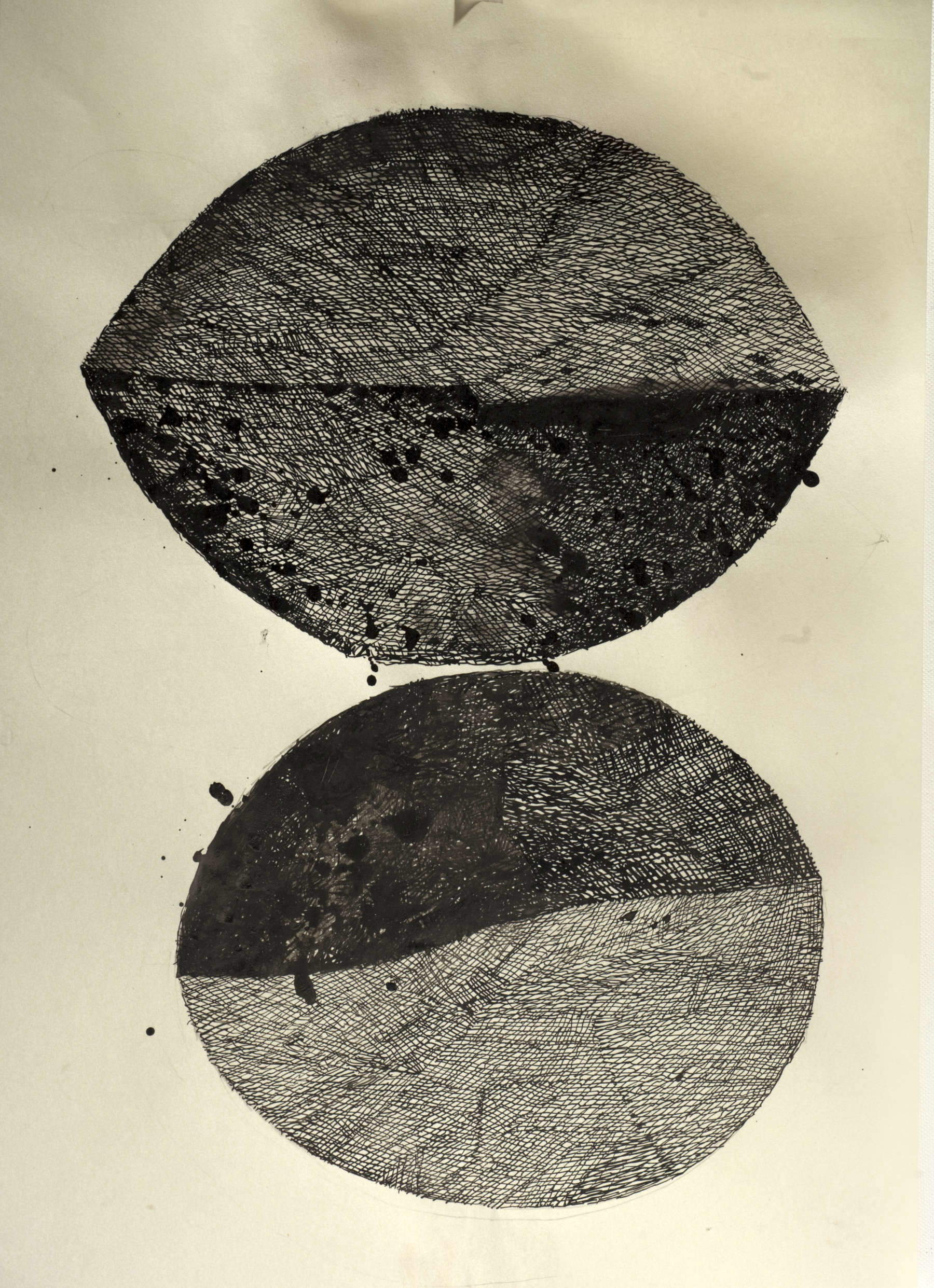

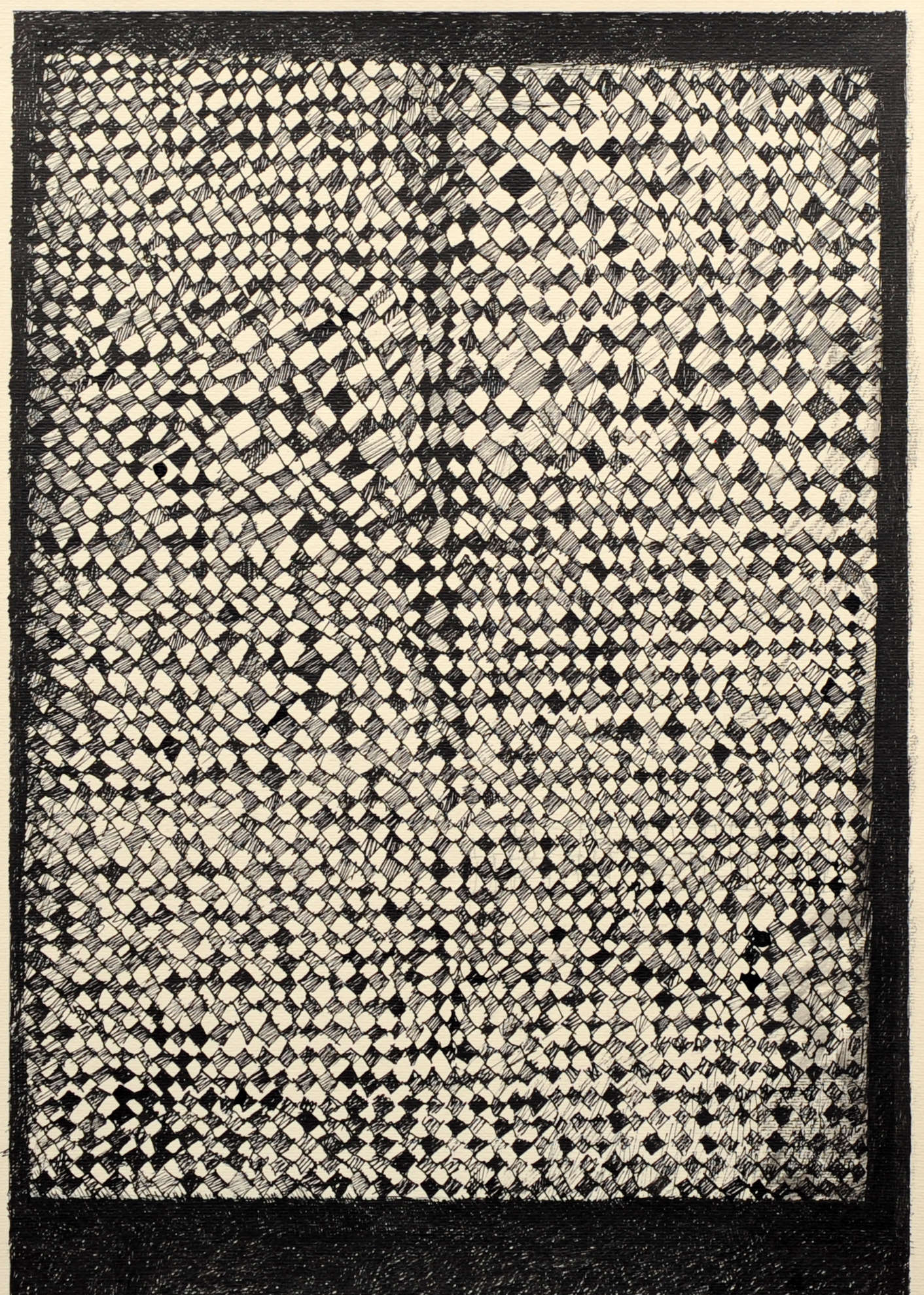

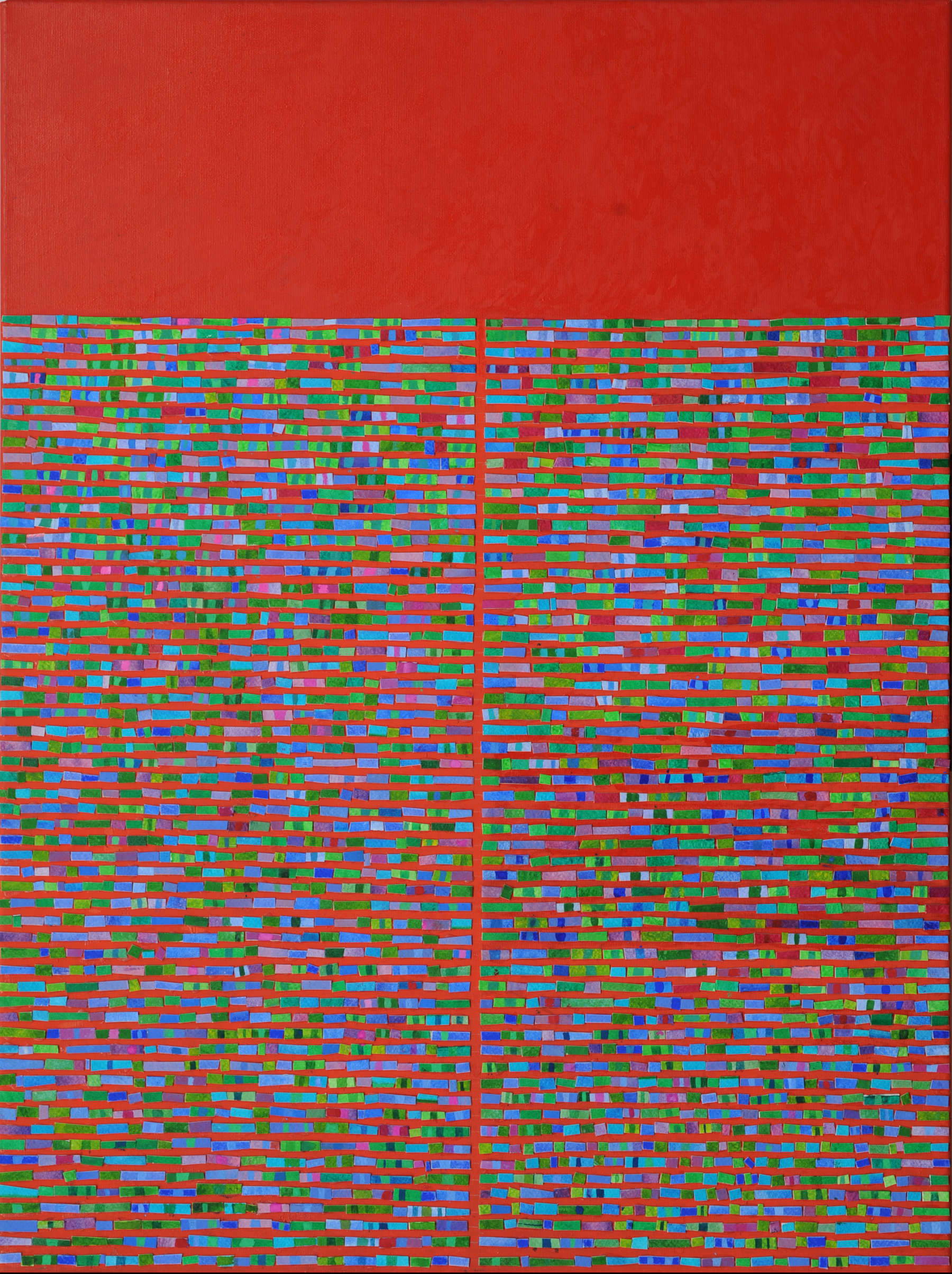

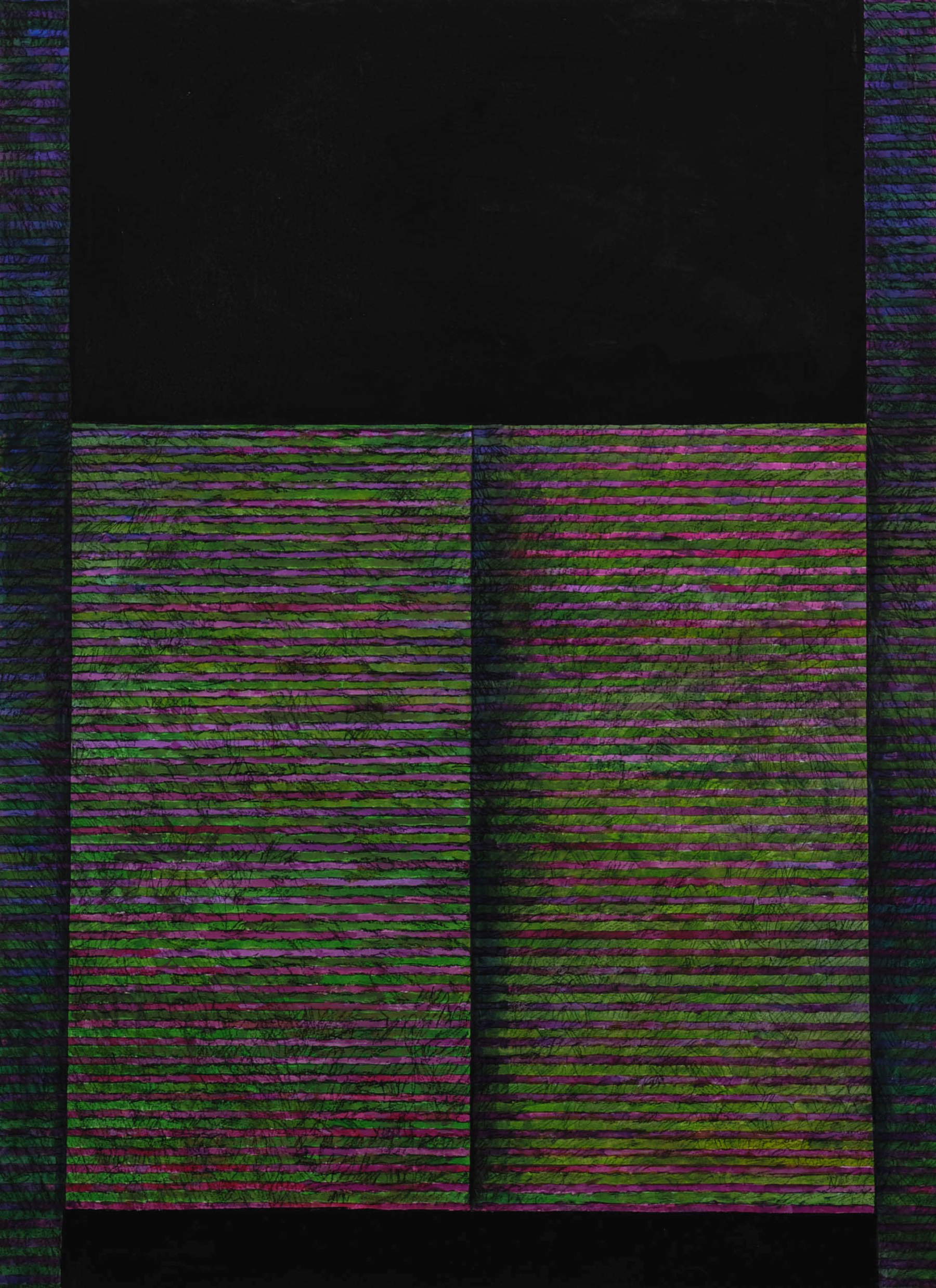

My artistic training, and not only, was close in constitution and cultural attraction to what I considered, since I was a boy, the greatest Friulian masters: the Basaldella brothers: Mirko, Dino, Afro and Zigaina. At a certain point in my existence as an artist, I changed my life, no longer having any interest in those art forms that had been my starting point. A conviction had matured in me that I could really create pictorial and mosaic works using color alone. The mental operation was embodied: so here is color brought to a point of incandescence that replaces line and renders sign useless. Behind my cultural choice to employ color as a fundamental element of my art were the continuous studies I made as a young man, and which continue to this day, on the complexity and psychology related to the world of color, on the radial visual stimuli determined by light, on rhythms, on tonal harmony, on the relationships that color has with music and mathematics. Ideal testaments to my education, were those of Balla, Kandinsky, Klee, Severini and Dorazio, evident more than is apparent from the dazzling power of their colors. On the other hand, I believe that art history is a work of continuous and patient reinterpretation for which the contemporary artist provides the historian, stimuli on the creative level, just as I believe the painting is born on the canvas. I could very well say that art is born from art, that art is play, artifice, and precisely the artificial element enhances the perceptive intelligence of the eye. In painting, drawing, or mosaic making, I have always tried to compare the relationship between multiple experiences and advanced themes that touch on the different linguistic codes of light and color. I have tried to construct linguistic and aesthetic values within the European tradition of abstractionism, and it is precisely in the continuous experimentation of the relationship between color and surface that I have glimpsed the possibility of making colors dialogue with each other, in the awareness that every chromatic relationship follows the rules of a momentary and unrepeatable creative empiricism. Not following fashions, I have tried for several years to pursue a conception of art as a discipline of form, as a poetic analysis of the linguistic structures of perception, based on the reciprocal relationships of color, light, space and movement. My paintings, mosaics, drawings, sculptures, and computer graphics works are intended to give “figure” to light, and are comparable to sources of energy that emit “radiation” conveying a vital and optimistic message.

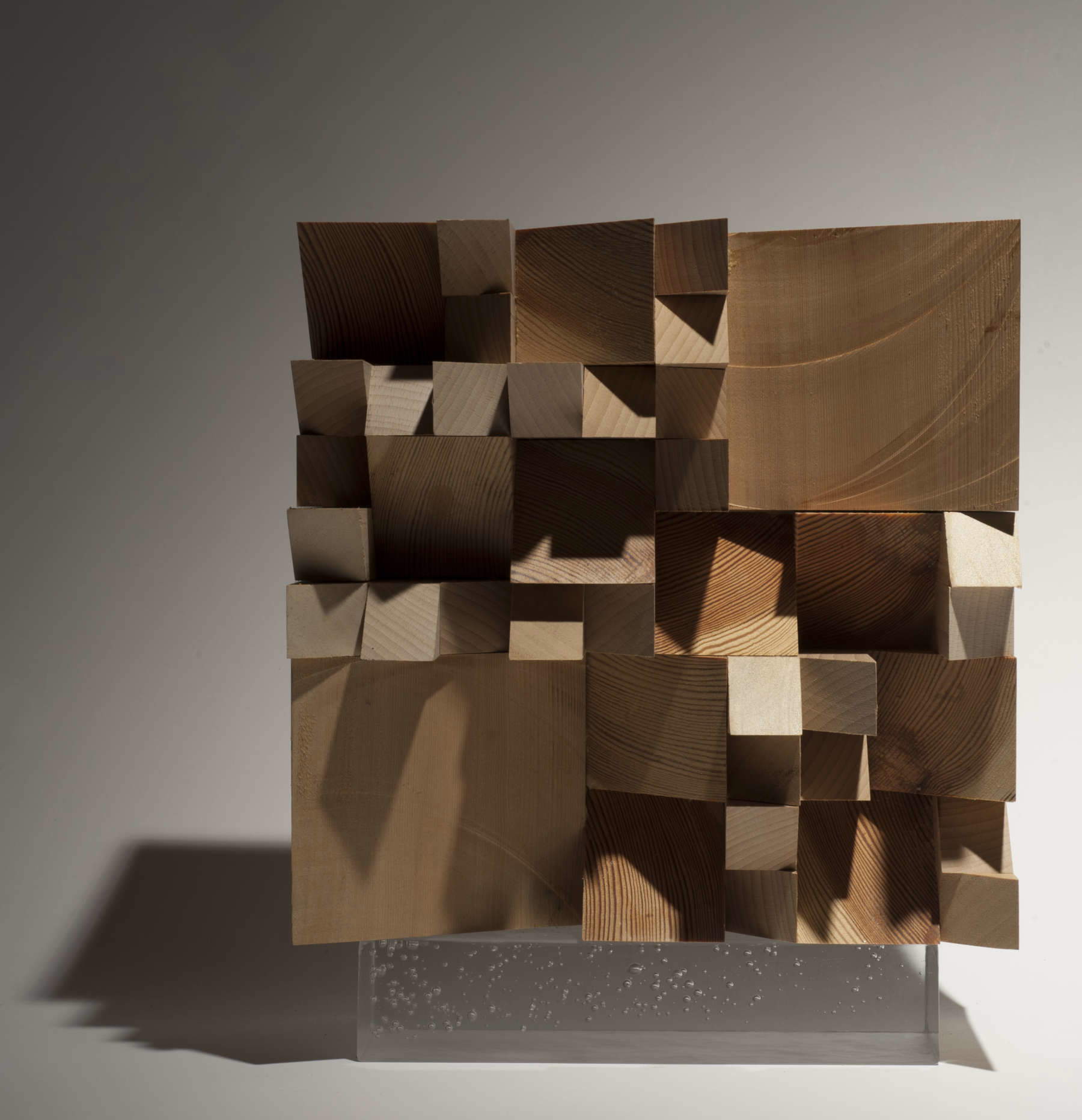

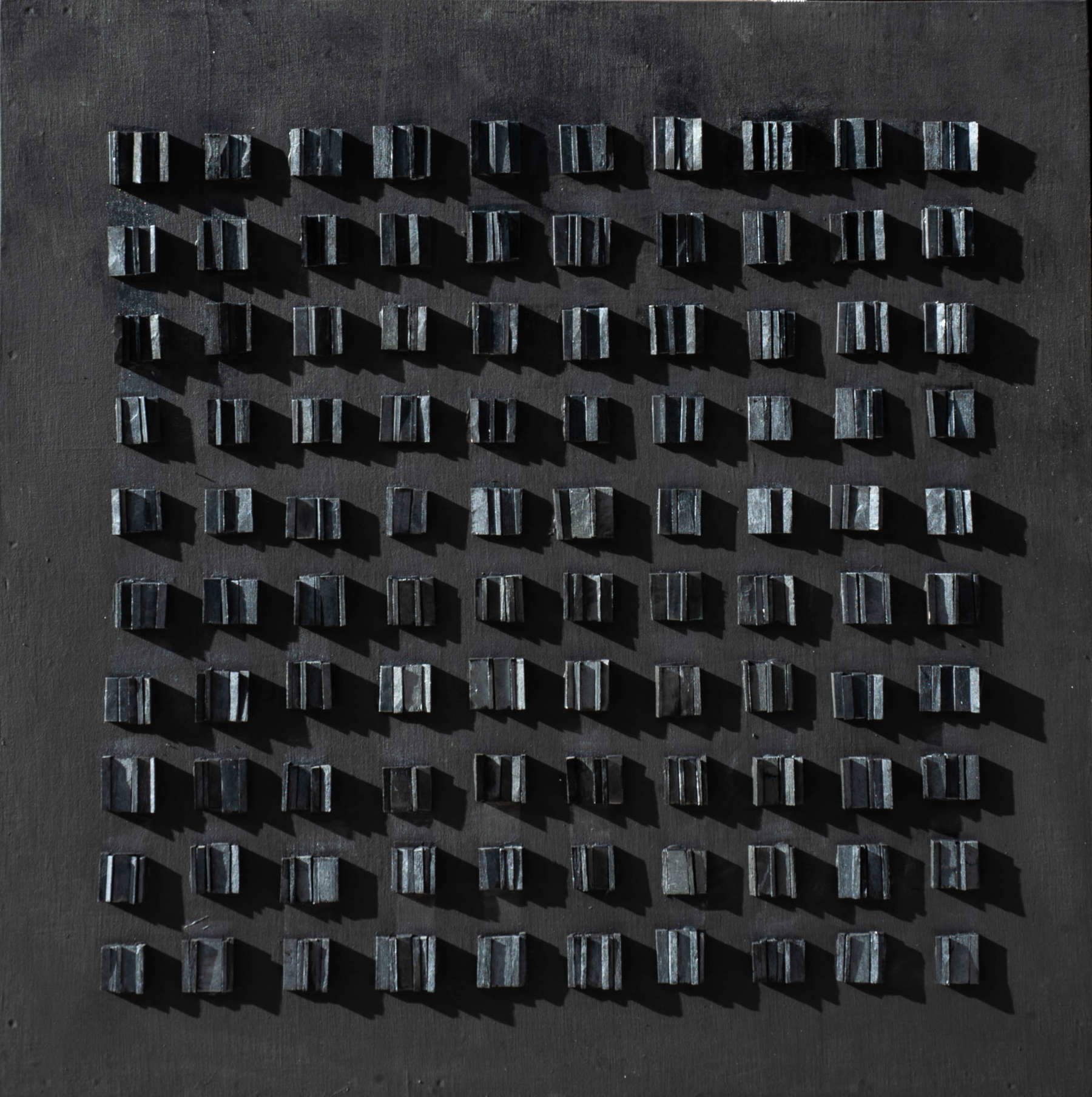

Among your many creations is the Libertycollection designed in 2007 for Trend Group S.p.A. in Vicenza, Italy: what were the goals you set from the beginning in conceiving this concept of modular decorative cladding in an industrial production context? Is the creation of a work of art a different thing from the creation of a high-end industrial product, and how does it differ? How do you define your experience working with Bisazza?

Liberty is a the collection designed to offer a product in which the sense of freedom is the absolute protagonist and the depth of the material “stained glass” becomes the most engaging decorative element. The color tones of the various formats are differently modulated, to obtain a pattern that celebrates the artistic current of the same name with modernity. The hand-cut transparent glass tesserae come to life thanks to the decisive or shaded reflections that mingle to create a dance of colors capable of embellishing any environment. Original interpretations of materials, unusual combinations of sizes and colors testify to my creative spirit that aims to be a forerunner of new trends. Past and future, tradition and technology merge and enrich sealing the innovative spirit at the service of contemporary decoration. In the laboratory of ideas, a strong synergy has been created so that the dialogue between the designer and the creator of matter is a continuous and prolific work in progress aimed at always offering new stylistic opportunities and therefore materials and finishes of great value. My entry into the Bisazza “world” took place in 1976 and was a decisive moment for me. Bisazza, with whom I had the opportunity to collaborate for a long time, offered me the opportunity for rapid professional growth, thanks to the meeting with artists, architects, designers of international caliber, in my regard the Bisazza people (I mean the founders of the company) behaved as patrons: in their companies I was able to freely develop my ideas, without being subjected to pressure of any kind. I was involved in important works such as the decorations of the London, Tokyo, and Naples subways, or such as the large-scale intervention carried out in the Lagos airport in Nigeria and in the mosaic decorations for the large Costa Crociere ships, where I was able to provide my professional contribution to artists such as Emilio Tadini, Sambonet, Concetto Pozzati, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Di Maria. A particularly meaningful experience.

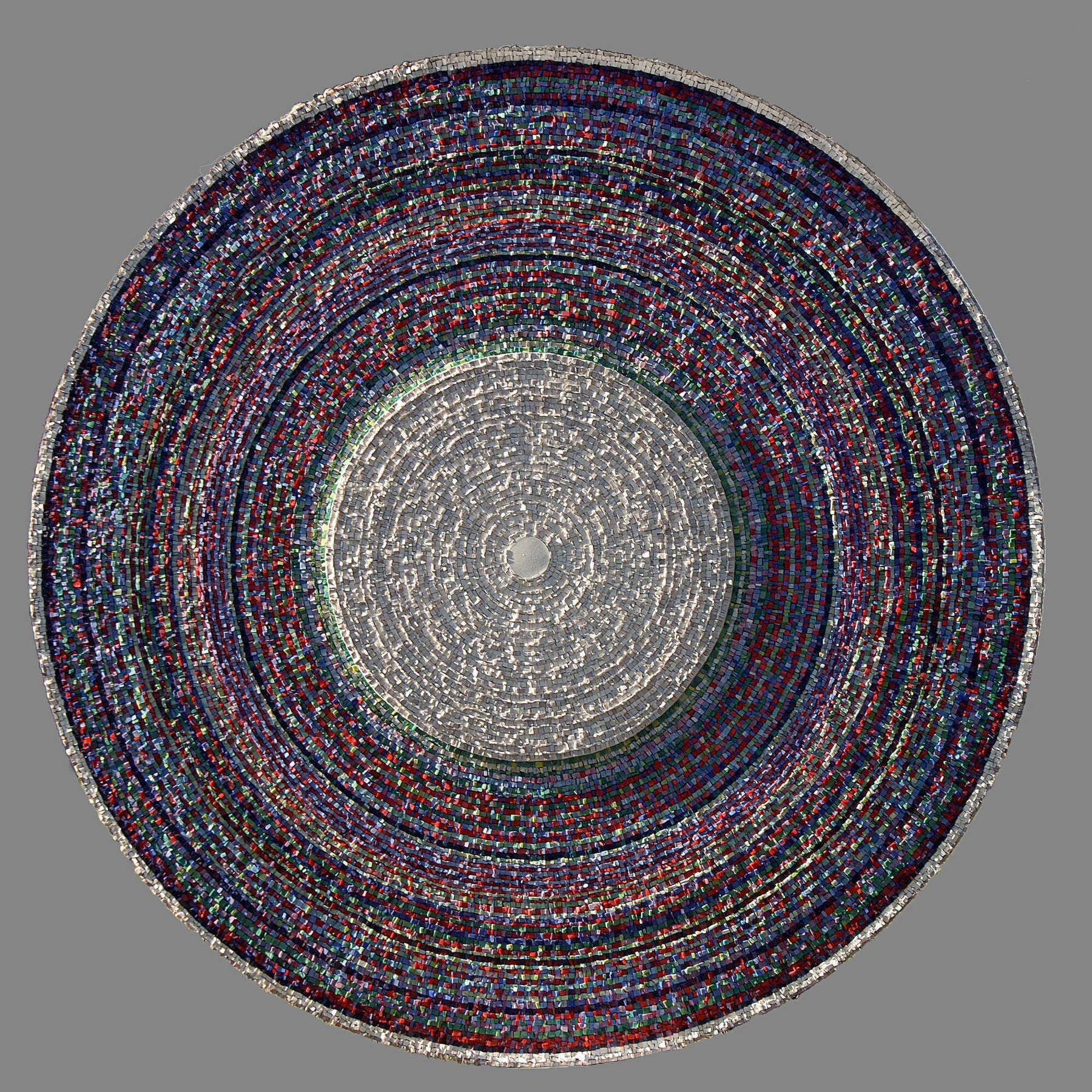

You have been called a pioneer in the application of computer graphics and multimedia technology applied to mosaic, how were you involved? Do you believe that what some call: “computer art” can be considered as such?

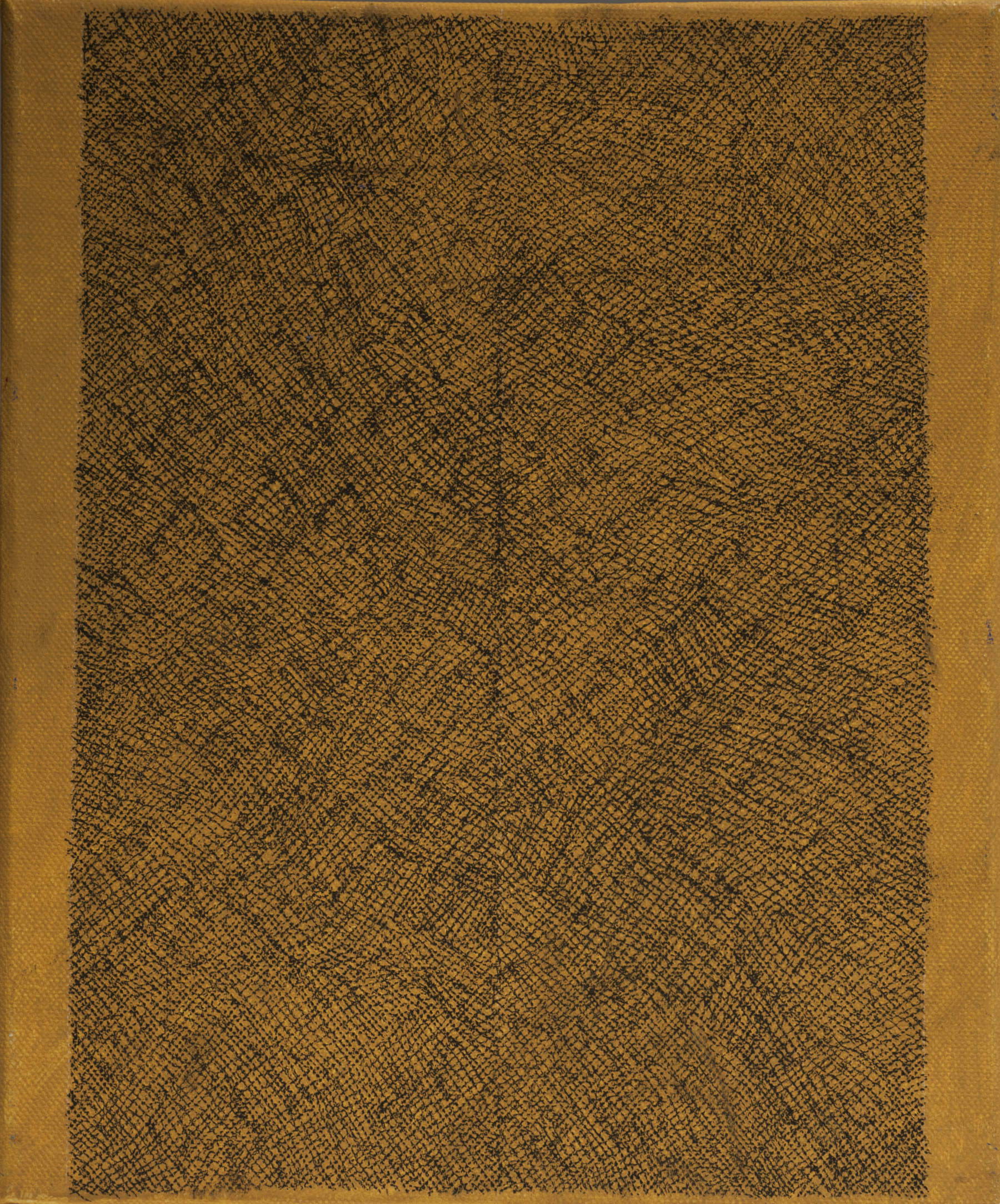

Beginning in 1994, and for almost three years, I conducted research and experimentation in computer graphics on behalf of Bisazza S.p.A. With the support of a major studio in Vicenza, Italy, I ventured into completely unfamiliar territories: complex systems of television shooting, photography in the dark, computerized colorimetry and applied computer science, absolutely indispensable means to master with the right expertise the sophisticated and expensive equipment I had at my disposal. I worked in a completely new way, alone and for a long time, inside a completely darkened three-by-four-meter room, committing myself to a computer graphics program applied to mosaics. The Company strongly wanted a specific program that could solve the problems related to large-scale mosaic decorations: the execution of large-scale mosaics obliges the use of specialized workers, requires long execution times, and the use of expensive materials demands the ability to be able to overcome logistical difficulties related to problems of preparation, experience, and execution skills of individual mosaicists: it will be necessary to convince them, without demeaning their pride and individualistic spirit, to transform their convictions into a common vision guaranteeing a final result that will gratify everyone. Computer graphics, founded on the “pixel = tile” equation, was welded to the “pioneering” research I had practiced passionately in the more mature period of my professional existence. Singular, rewarding and unthinkable experiences in those days, and not only that, I had been able to make use of the most modern operating systems and equipment. At last the program was a reality, and for the first time, it could be subjected to a major field test. Some of the most significant interventions in my career as a mosaicist and designer have a close relationship with architecture and outdoor spaces, which are the ones that most respond to the environmental vocation of mosaic. “Dressing” the exterior of a building means entering into a relationship with open space. Here is the most challenging test case for me at that particular time: the cladding of Bisazza’s Spilimberg plant, a four-hundred-square-meter outdoor decorative surface inspired by Piero Dorazio’s work Ginn Rull (1988). It will be placed on the staggered planes of the architectural structure, for more than a hundred meters of horizontal development. The mosaic design is scanned, enlarged and developed to then be made using industrially produced tiles that will then be placed orthogonally and assembled on 40,000 ciphered modules. The material executors of the mosaic are no longer traditional mosaicists, but careful and sensitive workers chosen from among the company’s staff. Everything that was hoped for and contemplated as a goal to be achieved has been accomplished: first, a planned and streamlined preparatory phase. Second: a sharp reduction in execution time that sometimes weighs excessively on the entire final cost. Third: a targeted system that allows the full potential of industrial materials to be dosed wisely, and in the best way. The end result is before everyone’s eyes: it is especially before the eyes of Piero Dorazio who will evaluate “Felix” the finished work.

You addressed the theme of lightning and I mention Rainbow Lightning. What was the message you wanted to convey through such a singular form? What did this professionally significant and important work represent for you?

Iridescent Lightning is placed at Ground Zero at the Path Station of the World Trade Center in New York City, inside the white ultra-modern building designed by Santiago Calatrava. The sun splits into numerous points of light as it rakes the tiles of the new mosaic mural, “Rainbow Lightning,” writes David W. Dunlap in the New York Times in February 2004. Rainbow Lightning is a three-dimensional mosaic work 37 feet long by 4 feet high, I’m told more than four million people walk past it every day, I hope they like it. I wanted to represent a zigzagging discharge of colorful energy, crossing space to unite two peoples, who although at different times have experienced two painful tragedies: the earthquake in Friuli on May 61976 and the attack on the twin towers on September 11, 2001. It is one of the most challenging works I have done in many ways, because of the circumstances for which it was created but also because of the reflection and on the technical and formal approach to contemporary mosaic, as a teaching tool and as a concrete experience for the students of the Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli. Saetta Iridescente turns out to be a dynamic sign of strong plastic value, amplified thanks to the shadow that is created by the distancing of the lightning bolt from the wall on which it is placed. Although it does not entirely cover it, it engages the entire space of the hall: it “runs through” it to its full extent, accompanying travelers with its undulatory movement. The work has been perfectly placed, which honors those who decided on the location and lighting, and fills me with justifiable pride as well

Can the exterior mosaic surface of Casa Rossetti in Sacile rightly be considered an example of minimalist decoration related to architecture and the effects of light?

Casa Rossetti in Sacile is a wall of light in the Zen spirit. The magnetic surface vibrates 34 meters in length and 4.5 meters in height: a mosaic made entirely of white pebbles using the direct-to-mortar technique, on a fiberglass substrate, the result is a prefabricated piece composed of a series of interlocking, light and flexible sectors that are reasonably priced and easy to install. Since the subject of the mosaic is light, everything is played on the effects of incident light that caresses and highlights the surface of the pebbles, generating ever-changing effects dependent on the varying position of the sun illuminating the tiles. The surface vibration becomes illusion and magic before the eyes of the observer, leading him to believe that the light comes from the very matter from which it was generated.

Many of your mosaic works gravitate around the form of the circle, I mention for example Light, Movement, Color.What did you want to communicate through this universal form?

Light, Movement, Color is my latest project. I was commissioned by the Management of the Friuli Mosaic School. to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of this world-famous institute. The work was to be created in the school’s internal laboratories, engaging all third-year students and those in the advanced course with the support of teachers for specific skills. I envisioned a large three-dimensional structure to be placed in a focal point of the large lawn within the schoolyard. The structure looks like a large double-sided disk four meters in diameter positioned vertically to the lawn from which it appears to arise. On both faces of the disk, a vibratory and pulsating “skin” expands to occupy the entire space of the structure. The work is in continuous dialogue with the surrounding architectural space, the urban space, the trees, the green lawn and the sky, in a context, where the space of Art becomes Public Art. In the face of the disk that looks at the inner space of the courtyard, the decoration appears to us as a relationship between sign/color and surface, and it is through this relationship that I glimpsed the possibility of making colors dialogue with each other, with the conviction that every color relationship follows the rules of a momentary and unrepeatable creative moment. The colored signs give form to light, and are like a source of energy that emits radiation which, in turn, conveys a message of vitality and energy. The facade of the record looking at the tree-lined avenue of the “Barbican,” is a reflection that every true artist should make in the years of awareness: when he or she cannot help but look around and put his or her image in relation to that of other artists, thus the evaluation of what little we have done becomes clear and inevitable, and that we are forced to admit that we could and should have done more, and that there is still so much more to do in the time we have left. Our conscience requires us to accept our size, which is that of a small tile in a large mosaic, within which we have inserted ourselves by natural tendency or by will, in a space that we will no longer have the chance to change. Without knowing it, we were as we are now, part of a linguistic repertoire, and aesthetic values that coincide with the Art of our time.

What are the significant projects that have most involved you in the last period, both creatively and personally? What projects are you currently working on?

After the major anthological exhibition in Palmanova in 2024, I resumed my work as an artist. On the occasion of the exhibition to be held in Spilimbergo in September 2025, I have designed some three-dimensional structures of considerable size covered entirely with a “mosaic skin.” They are decorative structures that are to characterize with their presence, the places that are most suitable to receive a public art intervention in those selected urban spaces, which exist in the city of mosaic. At this particular time, I am engaged in the writing of a book about mosaic. “Being Mosaic” is not a book that shows the beauty of mosaic from every era. It has special features, and compared to many books it is a kind of treatise/textbook. It begins with the construction of mosaic thinking that is fundamental to identifying mosaic as an expressive language and to distinguishing it sharply from mosaic subservient to painting. Mosaic, initially seen as play, comes to be transformed and becomes rhythm, alternation, mathematics, music, geometry, color. Materials, techniques, tradition and above all innovation that project us to our times through professional and singular experiences, demonstrated through the vision of the projects and the realism of the works created. And then I hope that there is time to do my work as an artist, there are visions, dreams and projects to be realized through that putting oneself out there every day, which after all is the real salt of life.

The author of this article: Vera Belikova

Vera Belikova è un'artista e designer di mosaici, formata presso la Scuola Mosaicisti del Friuli a Spilimbergo, e vive a Venezia. È specializzata in mosaici artigianali, realizzati fedelmente con antiche tecniche di lavorazione e integrati con le nuove tecnologie di produzione digitale. Nel 2018 ha realizzato due sculture musive in Puglia, una delle quali come artista ospite dell'Apulia Land Art Festival. Nel 2018 ha vinto lo Sprech Agorà Design Contest, presentando un pouf con intarsi in mosaico, che è stato esposto alla Milano Design Week. Nel 2020 ha esposto accanto a Paola Navone ed Elena Salmistraro nella Galleria Superstudio+ di Milano nella mostra di arte e design al femminile curata dalla sua fondatrice Gisella Borioli. Nel 2024 ha installato una stele dedicata ai 700 anni dalla morte di Marco Polo in città di Almaty. Vera collabora inoltre alla realizzazione di terrazzo alla veneziana con inserti in mosaico. Le sue soluzioni musive sono decorazioni essenziali che esaltano il movimento delle tessere, il colore dei materiali naturali e artificiali e la luce che si riflette sulla superficie, creando effetti d'ombra unici.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.