I believe in slow, thoughtful, constructed and poetic photography. Interview with Mario Cresci

Until June 18, 2023 at the Gamba Castle - Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of the Aosta Valley, the exhibition Mon cher Abbé Bionaz! Mario Cresci a photographer for the Aosta Valley, curated by Luca Fiore and produced by Le Macchine Effimere. It is a tribute to the territory, history and culture, especially rural Valle d’Aosta, through the works of Mario Cresci (Chiavari, 1942), one of the masters of Italian photography, who had a deep relationship with Valle d’Aosta throughout his life. We asked him to tell us about not only the current exhibition at Castello Gamba, but also about aspects of his production and his being a photographer. The interview is by Ilaria Baratta.

IB. Your exhibition at Castello Gamba revolves around the sixteen photographs preserved in the regional collections that you took in 1990 to narrate the rural world of Valle d’Aosta. Can you tell us about that experience? What do these shots depict?

MC. The exhibition starts right on the ground floor with these shots from 1990. I was in Valle d’Aosta for the first time on assignment from the Region for a photographic reportage dedicated to the rural communities of Valle d’Aosta. It was a subject dear to me because I was coming from Basilicata and was therefore used to dealing with ethno-anthropological aspects and rural material culture. These are sixteen black-and-white shots taken in the Aosta Valley, especially in the interior areas, countryside and plateaus. The Aosta Valley is a region rich in extraordinary perspectives. On the one hand I got on well with the people, the farmers, the artisans, on the other hand the landscape was obviously different from that of Basilicata. Once I finished my work through this experience, I then left the sixteen photographs in the region’s archives, which then became part of the Castello Gamba photographic archive. Now after so many years I found myself revisiting those photographs.

How does the exhibition journey continue?

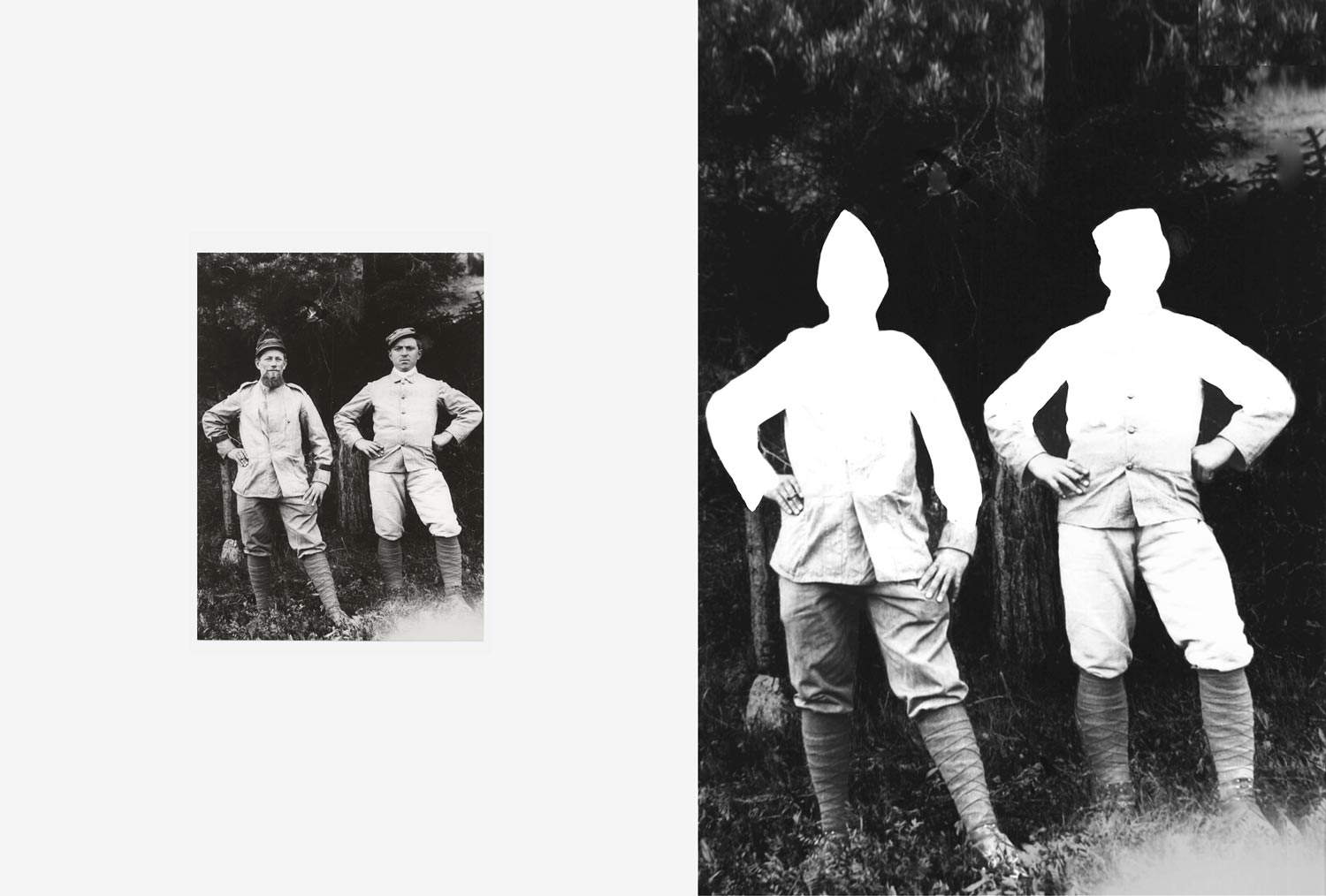

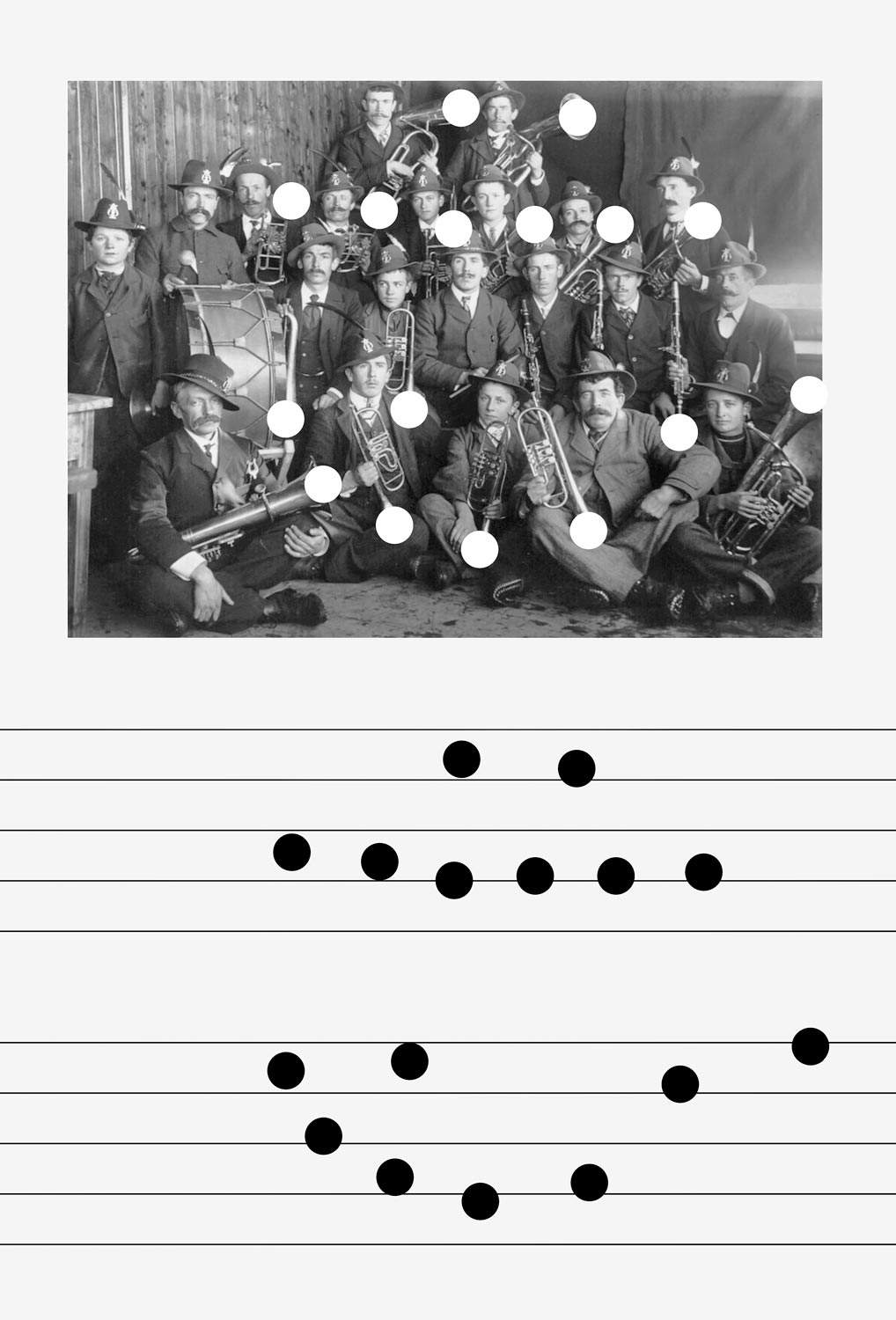

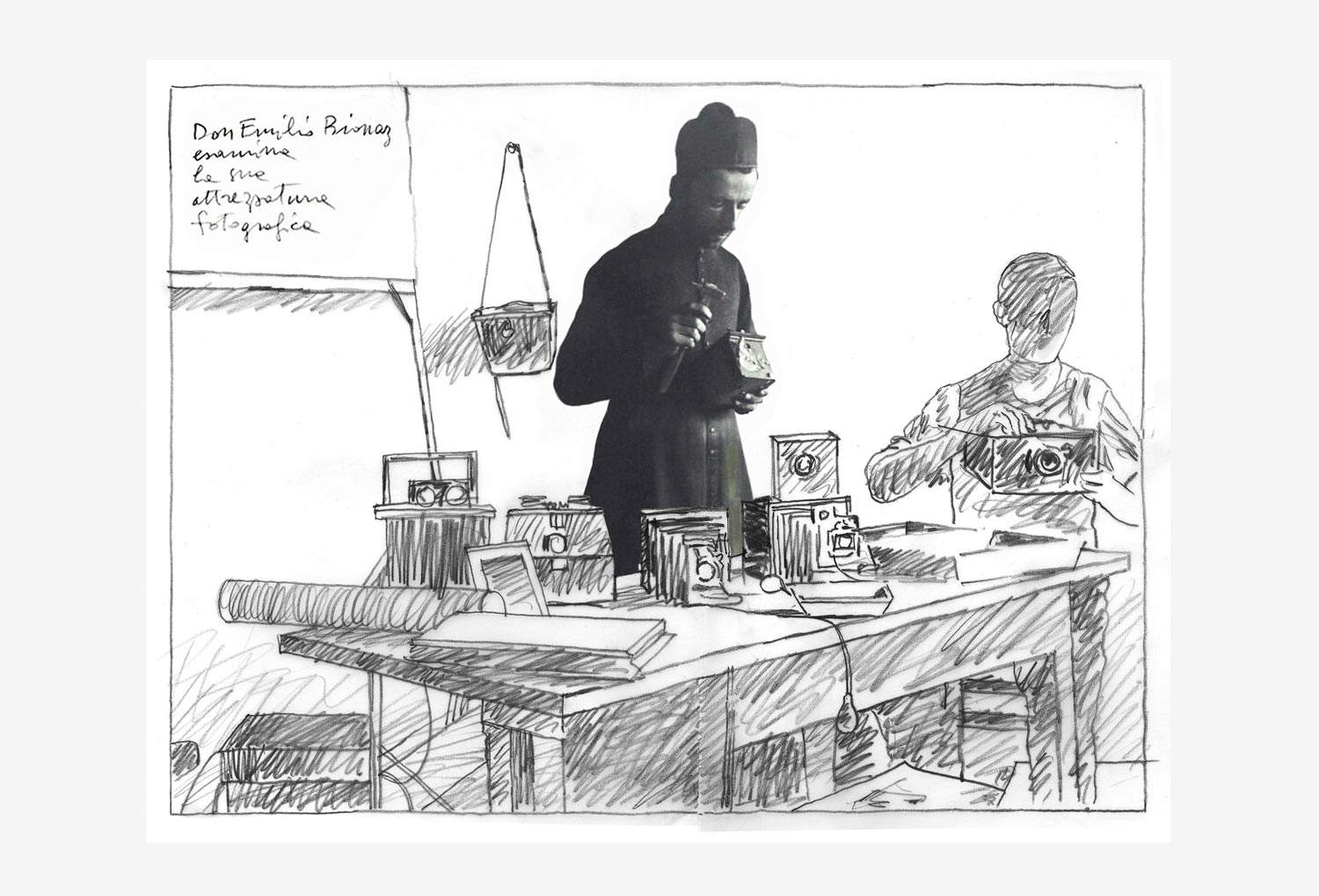

The exhibition is divided into three parts, on the three floors of Gamba Castle. On the ground floor, as mentioned above, the photographs from 1990 are on display. The next floor is a groundbreaking moment for me because in the photographic archives of the Gamba Castle I came across the photographs of a photographer priest, Émile Bionaz, who in the early twentieth century was the parish priest for thirty-seven years of a small town in the Aosta Valley, Saint-Nicolas: he photographed families, baptisms, weddings, children, schools, and above all the whole rural society of those years. I digitally processed those photos and reinterpreted them without altering the original meaning of the shot. The result was twenty photographic prints, new. The subjects are the ones he had chosen: groups of families, groups of farmers, and also situations related to agricultural activity. I then interpreted these shots with a contemporary vision. The question I asked myself was, “But what is the point of reviewing old photos and then redoing them in the same places? Let us rather work on the images of those who came before us and see what are the points of encounter between my gaze and the gaze of Bionaz.” It is therefore a kind of work on time: his time and my time. I could say in quotes that I worked together with him, and it was very pleasant, because it also opens up a reflection on photographic archives in Italy. We have a huge heritage that remains there, which is often abandoned and often needs to be arranged, studied, as a historical memory of our country. On the still next floor, however, there are six large unframed photographs, which are the graphic imprints left by the objects that I encountered in the Museum of Aosta Valley Crafts in Fénis. I photographed them and then transferred them into graphic elements like large posters, where there is no longer color or matter, but shadow. Like big logos, coming as I do from the world of design and graphics, I tried to actualize even more the photographic work I had done from 1990 to recent days, until I made these six proposals that are intended to have an educational value as well. My intention in fact, together with that of curator Luca Fiore, was to present a method of work and research that can also be used in schools and by photography and graphic design enthusiasts, drawing on the historical memories of their own region, their own museums, their own land.

As mentioned earlier, throughout your production you have given special emphasis to the rural world, to peasant traditions. Why this interest?

My interest started in the late 1960s, when I was part of a five-person research group consisting of architects, a sociologist, and I was in charge of photography. From Venice we moved to Tricarico, Basilicata, for the master plan of this small town near Matera of 6,000 inhabitants. For the first time I found myself catapulted from Venice to the South, to the Mezzogiorno, and I was dazzled by this region, probably because I come from a peasant family (my paternal grandfather was from the Ligurian countryside, my maternal grandfather was a Sardinian, from the hinterland of Sardinia). So probably for my own personal reasons I was fascinated by the rural world of this land. From 1967 until before the 1980s I lived in Matera, I started a family, my two children were born in Matera, I integrated there, and I did a lot of work in the field not only of popular cultures but also of public agencies and the city; I worked in the field of photographic and graphic design, also opening a studio. The issue of folk culture is ancient, very Mediterranean and Italian, because it is related to an idea of integration of human activities with nature, the environment, knowledge of the climate, the ability to use materials; it is something that has to do with the culture of homo faber that still the peasant then had. I became as passionate about this world as, for example, Carlo Levi or Olivetti himself was passionate about it. Moreover, my teacher, sociologist Aldo Musacchio, was a southerner who taught sociology at the Design Course in Venice where I was a student: thus was born my passion for the rural world and especially for the regions of the Mezzogiorno, for the political and social problems of a land I did not know. It was a spontaneous enlightenment that then allowed me to work there for many years.

Instead, what links you to the Aosta Valley? What fascinated you about this territory?

I had a friend, an extraordinary graphic designer from Aosta, Franco Balan, whom I used to visit often. He had his studio near the Roman excavations in the historic center of Aosta, and he had a lovely little country house along the river before going up to the city. This friendship often took me to the Aosta Valley, we used to go on long drives together but also on foot, and it was he, although he is unfortunately gone now, who introduced me to this region albeit in a fairly superficial way. Since he then passed away, I did not return there for many years. The Aosta Valley was for me in those years a region also rich in historical memory. The manual skills, the know-how of this people has always fascinated me also as a function of teaching, which I still try to pass on to my students in Urbino (I teach photography and graphics at ISIA). We are in a time when the virtual, artificial intelligence and all the new technologies are taking us to levels of advanced technologies and we are really losing the manuality of writing, of drawing; this recovery of manuality and history of making is very important in my opinion, because it means combining the past with the present. If we don’t know the past it is useless to move forward with the present. This is the lesson that in Valle d’Aosta seemed similar to that of certain regions in the South, such as Puglia, Basilicata, Campania, but also to that of certain regions in the North, such as Carnia, Alto Adige. The desire is that through art and photography we can still think in terms of doing, but in a conscious way, not in a rhetorical way; I think it is useful to young people, to new generations. On an artistic level, I like the idea that an author is also committed to disseminating such a message through his work. The Aosta Valley has always provided very interesting exhibitions in this aspect as well. I have always been comfortable in this region, and I would like to continue to have a relationship with the museums and archives of the Aosta Valley.

What kind of photographer do you define yourself as? Are you more instinctive or do you wait for the right moment to shoot Or do you construct your photographs?

I am not a photojournalist, I like instinctual photography and when it happens to me I like to do it too, because Cartier-Bresson also theorized this question of the magic moment, of the fleeting moment that is caught by the camera, but I believe much more in a slow, thought out, constructed, at the same time poetic photography, not stiffened by the optics of the camera and always motivated by the subjective desire to express ourselves through the image. It is the reality that we see that we alter. I no longer feel that I am photographing reality, but that I am creating from time to time inner landscapes, images that I have inside me and that I am constantly going to verify with my gaze outside myself. Photography for me is the conjunction between one’s own feeling and the external gaze. The union between the experienced, the inner seeing and the outer seeing through the photographic image creates images that are internalized, and if they are not, it means that they were made only for aesthetic taste, and that does not interest me. Discovering and researching: that is my assumption, what I have always tried to do in so many years of work.

How much experimentation is there in your shots?

Whenever you take a picture you are always experimenting. Curiosity leads to experimentation. More than experimentation, however, I would prefer to talk about research. Because to talk about research is to consider photography a work like life itself. During the day I look at things without thinking about the fact that I don’t have my camera with me, I look, I think, and then if I decide to take a picture I do it, otherwise the look is enough. We are like a human camera that internalizes what we see, however, photography adds something more. Photography is a medium that is still constantly changing technologically; smartphones are now becoming little cameras. Everyone can now take pictures, and that is very nice, but it would be good if we started to study the language of photography in more depth. That children be taught in school what it means to use audiovisual media to produce and to create images. However, it will be increasingly difficult in the coming years to call photography something that is already beginning to creak, because already the idea of a matrix and a negative no longer exists. It is a file that can be duplicated, mystified. In this sense we can work within a new language, a new field of research that pertains to artists, communicators, journalists, those who produce information, and especially at the creative level I would see more and more teaching this sense of contemporary art in schools. Doing photography is a search for meaning in my living, in my everyday life through projects that allow me to propose narratives and stories, as in these photographs of the Aosta Valley that relate to History, to the past and to the present.

In conclusion, what suggestions would you feel like giving to a young photographer?

I went to a very good school of Design in the early 1960s and it served me very well. To learn photography to a young photographer I would say to keep on taking pictures, but without thinking about being indoctrinated by photographic dogmas and thinking. He should first learn about the language of photography, and then deciding what specifically to devote himself to, e.g. photojournalist, fashion photographer and so on, will come later. At the educational level, I for example needed literature texts more instead of photography textbooks. Reading Calvino or the great writers of the 20th century who could write visualizing their thoughts in an extraordinary way created images in me. The advice is to absorb what you see in the theater, in the cinema, what you read in books, in newspapers, and make it into material for study, for reconnaissance, for continuous verification, knowing how to recognize what interests us most. Photography schools are only useful on a technical level; if a young photographer wants to learn to be an author who gives photography a more extended meaning, to be like a writer, then I would advise reading and seeing a lot, studying and feeling engaged in the society in which he or she lives and never feeling like the navel of the world. So work in social work with the ambition to do research, vary interests a lot and take pictures all the time, every day, even with a smartphone, like taking notes, and then draw every now and then, keep a booklet in your pocket for notes. Using the cell phone as a pen, putting away pictures and creating one’s own archive, not throwing anything away, putting dates, places, and references to one’s work.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.